Endothelin

| Endothelin family | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Endothelin | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00322 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001928 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00243 | ||||||||

| SCOP | 1edp | ||||||||

| SUPERFAMILY | 1edp | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 147 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 3cmh | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Endothelin 1 | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | EDN1 |

| Entrez | 1906 |

| HUGO | 3176 |

| OMIM | 131240 |

| RefSeq | NM_001955 |

| UniProt | P05305 |

| Other data | |

| Locus | Chr. 6 p23-p24 |

| Endothelin 2 | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | EDN2 |

| Entrez | 1907 |

| HUGO | 3177 |

| OMIM | 131241 |

| RefSeq | NM_001956 |

| UniProt | P20800 |

| Other data | |

| Locus | Chr. 1 p34 |

| Endothelin 3 | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | EDN3 |

| HUGO | 3178 |

| OMIM | 131242 |

| RefSeq | NM_000114 |

| UniProt | P14138 |

| Other data | |

| Locus | Chr. 20 q13.2-q13.3 |

Endothelins are peptides with receptors and effects in many body organs.[1][2] Endothelin constricts blood vessels and raises blood pressure. The endothelins are normally kept in balance by other mechanisms, but when overexpressed, they contribute to high blood pressure (hypertension), heart disease, and potentially other diseases.[1][3]

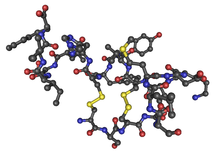

Endothelins are 21-amino acid vasoconstricting peptides produced primarily in the endothelium having a key role in vascular homeostasis. Endothelins are implicated in vascular diseases of several organ systems, including the heart, lungs, kidneys, and brain.[4][5] As of 2018, endothelins remain under extensive basic and clinical research to define their roles in several organ systems.[1][6][7][8]

Contents

1 Etymology

2 Isoforms

3 Antagonists

4 Physiological effects

5 Disease involvement

6 Gene regulation

7 References

8 External links

Etymology

Endothelins derived the name from their isolation in cultured endothelial cells.[1][9]

Isoforms

There are three isoforms of the peptide (identified as ET-1, -2, -3) with varying regions of expression and binding to at least four known endothelin receptors, ETA, ETB1, ETB2 and ETC.[1][10]

Antagonists

Earliest antagonists discovered for ETA were BQ123, and for ETB, BQ788.[9] An ETA-selective antagonist, ambrisentan was approved for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension in 2007, followed by a more selective ETA antagonist, sitaxentan, which was later withdrawn due to potentially lethal effects in the liver.[1]Bosentan was a precursor to macitentan, which was approved in 2013.[1]

Physiological effects

Endothelins are the most potent vasoconstrictors known.[1][11] Overproduction of endothelin in the lungs may cause pulmonary hypertension, which was treatable in preliminary research by bosentan, sitaxentan or ambrisentan.[1]

Endothelins have involvement in cardiovascular function, fluid-electrolyte homeostasis, and neuronal mechanisms across diverse cell types.[1] Endothelin receptors are present in the three pituitary lobes[12] which display increased metabolic activity when exposed to endothelin-1 in the blood or ventricular system.[13]

ET-1 contributes to the vascular dysfunction associated with cardiovascular disease, particularly atherosclerosis and hypertension.[14] The ETA receptor for ET-1 is primarily located on vascular smooth muscle cells, mediating vasoconstriction, whereas the ETB receptor for ET-1 is primarily located on endothelial cells, causing vasodilation due to nitric oxide release.[14]

The binding of platelets to the endothelial cell receptor LOX-1 causes a release of endothelin, which induces endothelial dysfunction.[15]

Disease involvement

The ubiquitous distribution of endothelin peptides and receptors implicates involvement in a wide variety of physiological and pathological processes among different organ systems.[1] Among numerous diseases potentially occurring from endothelin dysregulation are:

- several types of cancer[16][17]

cerebral vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage[18]

arterial hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, and other cardiovascular disorders[17]

pain mediation[19]

cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure[17]

- Dengue haemorrhagic fever

- Type II diabetes

- some cases of Hirschsprung disease

In insulin resistance the high levels of blood insulin results in increased production and activity of ET-1, which promotes vasoconstriction and elevates blood pressure.[20]

ET-1 impairs glucose uptake in the skeletal muscles of insulin resistant subjects, thereby worsening insulin resistance.[21]

In preliminary research, injection of endothelin-1 into a lateral cerebral ventricle was shown to potently stimulate glucose metabolism in specified interconnected circuits of the brain, and to induce convulsions, indicating its potential for diverse neural effects in conditions such as epilepsy.[22] Receptors for endothelin-1 exist in brain neurons, indicating a potential role in neural functions.[17]

Gene regulation

The endothelium regulates local vascular tone and integrity through the coordinated release of vasoactive molecules. Secretion of endothelin-1 (ET-1)1 from the endothelium signals vasoconstriction and influences local cellular growth and survival. ET-1 has been implicated in the development and progression of vascular disorders such as atherosclerosis and hypertension. Endothelial cells upregulate ET-1 in response to hypoxia, oxidized LDL, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and bacterial toxins. Initial studies on the ET-1 promoter provided some of the earliest mechanistic insight into endothelial-specific gene regulation. Numerous studies have since provided valuable insight into ET-1 promoter regulation under basal and activated cellular states.

The ET-1 mRNA is labile with a half-life of less than an hour. Together, the combined actions of ET-1 transcription and rapid mRNA turnover allow for stringent control over its expression. It has previously been shown that ET-1 mRNA is selectively stabilized in response to cellular activation by Escherichia coli O157:H7-derived verotoxins, suggesting ET-1 is regulated by post-transcriptional mechanisms. Regulatory elements modulating mRNA half-life are often found within 3'-untranslated regions (3'-UTR). The 1.1-kb 3'-UTR of human ET-1 accounts for over 50% of the transcript length and features long tracts of highly conserved sequences including an AU-rich region. Some 3'-UTR AU-rich elements (AREs) play important regulatory roles in cytokine and proto-oncogene expression by influencing half-life under basal conditions and in response to cellular activation. Several RNA-binding proteins with affinities for AREs have been characterized including AUF1 (hnRNPD), the ELAV family (HuR, HuB, HuC, HuD), tristetraprolin, TIA/TIAR, HSP70, and others. Although specific mechanisms directing ARE activity have not been fully elucidated, current models suggest ARE-binding proteins target specific mRNAs to cellular pathways that influence 3'-polyadenylate tail and 5'-cap metabolism.

Recent studies have revealed a functional link between AUF1, heat shock proteins and the ubiquitin-proteasome network. Proteasome inhibition by chemical inhibition or heat shock was shown to stabilize a model ARE-containing mRNA whereas promotion of cellular ubiquitination pathways was shown to accelerate ARE mRNA turnover. Studies with in vitro proteasome preparations suggest that the proteasome itself may possess ARE-specific RNA destabilizing activity. The ARE-binding protein AUF1 has been linked to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. AUF1 mRNA destabilizing activity has been positively correlated with its level of polyubiquitination and has been shown to interact with a member of the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating protein family. Furthermore, under conditions of cellular heat shock AUF1 associates with heat shock protein 70 (HSP70), which itself possesses ARE binding activity.

The ET-1 transcript is constitutively destabilized by its 3'-UTR through two destabilizing elements, DE1 and DE2. DE1 functions through a conserved ARE by the AUF1-proteasome pathway and is regulated by the heat shock pathway.[23]

References

^ abcdefghijk Davenport AP, Hyndman KA, Dhaun N, Southan C, Kohan DE, Pollock JS, Pollock DM, Webb DJ, Maguire JJ (April 2016). "Endothelin". Pharmacological Reviews. 68 (2): 357–418. doi:10.1124/pr.115.011833. PMC 4815360. PMID 26956245..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Kedzierski RM, Yanagisawa M (2001). "Endothelin system: the double-edged sword in health and disease". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 41: 851–76. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.851. PMID 11264479.

^ Maguire JJ, Davenport AP (December 2014). "Endothelin@25 - new agonists, antagonists, inhibitors and emerging research frontiers: IUPHAR Review 12". British Journal of Pharmacology. 171 (24): 5555–72. doi:10.1111/bph.12874. PMC 4290702. PMID 25131455.

^ Agapitov AV, Haynes WG (March 2002). "Role of endothelin in cardiovascular disease". Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. 3 (1): 1–15. doi:10.3317/jraas.2002.001. PMID 11984741.

^ Schinelli S (2006). "Pharmacology and physiopathology of the brain endothelin system: an overview". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 13 (6): 627–38. doi:10.2174/092986706776055652. PMID 16529555.

^ Kuang HY, Wu YH, Yi QJ, Tian J, Wu C, Shou WN, Lu TW (March 2018). "The efficiency of endothelin receptor antagonist bosentan for pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Medicine. 97 (10): e0075. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010075. PMID 29517668.

^ Iljazi A, Ayata C, Ashina M, Hougaard A (March 2018). "The Role of Endothelin in the Pathophysiology of Migraine-a Systematic Review". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 22 (4): 27. doi:10.1007/s11916-018-0682-8. PMID 29557064.

^ Lu YP, Hasan AA, Zeng S, Hocher B (2017). "Plasma ET-1 Concentrations Are Elevated in Pregnant Women with Hypertension -Meta-Analysis of Clinical Studies". Kidney and Blood Pressure Research. 42 (4): 654–663. doi:10.1159/000482004. PMID 29212079.

^ ab Tuma RF, Durán WN, Ley K (2008). Microcirculation (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 305–307. ISBN 978-0-12-374530-9.

^ Boron WF, Boulpaep EL (2009). Medical physiology a cellular and molecular approach (2nd International ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 480. ISBN 978-1-4377-2017-4.

^ Craig CR, Stitzel RE (2004). Modern pharmacology with clinical applications (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-7817-3762-3.

^ Lange M, Pagotto U, Renner U, Arzberger T, Oeckler R, Stalla GK (May 2002). "The role of endothelins in the regulation of pituitary function". Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes. 110 (3): 103–12. doi:10.1055/s-2002-29086. PMID 12012269.

^ Gross PM, Wainman DS, Espinosa FJ (August 1991). "Differentiated metabolic stimulation of rat pituitary lobes by peripheral and central endothelin-1". Endocrinology. 129 (2): 1110–2. doi:10.1210/endo-129-2-1110. PMID 1855455.

^ ab Böhm F, Pernow J (2007). "The importance of endothelin-1 for vascular dysfunction in cardiovascular disease" (PDF). CARDIOVASCULAR RESEARCH. 76 (1): 8–18. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.06.004. PMID 17617392.

^ Kakutani M, Masaki T, Sawamura T (2000). "A platelet-endothelium interaction mediated by lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (1): 360–364. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2016.10.010. PMC 26668. PMID 10618423.

^ Bagnato A, Rosanò L (2008). "The endothelin axis in cancer". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 40 (8): 1443–51. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2008.01.022. PMID 18325824.

^ abcd Kawanabe Y, Nauli SM (January 2011). "Endothelin". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 68 (2): 195–203. doi:10.1007/s00018-010-0518-0. PMC 3141212. PMID 20848158.

^ Macdonald RL, Pluta RM, Zhang JH (May 2007). "Cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage: the emerging revolution". Nature Clinical Practice Neurology. 3 (5): 256–63. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0490. PMID 17479073.

^ Hasue F, Kuwaki T, Kisanuki YY, Yanagisawa M, Moriya H, Fukuda Y, Shimoyama M (2005). "Increased sensitivity to acute and persistent pain in neuron-specific endothelin-1 knockout mice". Neuroscience. 130 (2): 349–58. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.036. PMID 15664691.

^ Potenza MA, Addabbo F, Montagnani M (September 2009). "Vascular actions of insulin with implications for endothelial dysfunction". American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 297 (3): E568–77. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00297.2016. PMID 19491294.

^ Shemyakin A, Salehzadeh F, Böhm F, Al-Khalili L, Gonon A, Wagner H, Efendic S, Krook A, Pernow J (May 2010). "Regulation of glucose uptake by endothelin-1 in human skeletal muscle in vivo and in vitro". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 95 (5): 2359–66. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-1506. PMID 20207830.

^ Chew BH, Weaver DF, Gross PM (May 1995). "Dose-related potent brain stimulation by the neuropeptide endothelin-1 after intraventricular administration in conscious rats". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 51 (1): 37–47. PMID 7617731.

^ Mawji IA, Robb GB, Tai SC, Marsden PA (March 2004). "Role of the 3'-untranslated region of human endothelin-1 in vascular endothelial cells. Contribution to transcript lability and the cellular heat shock response". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (10): 8655–67. doi:10.1074/jbc.M312190200. PMID 14660616.

External links

Endothelins at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)