Ernst Thälmann

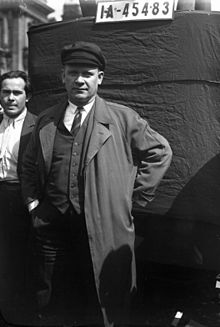

Ernst Thälmann | |

|---|---|

Ernst Thälmann (1932) | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1886-04-16)16 April 1886 Hamburg, German Empire |

| Died | 18 August 1944(1944-08-18) (aged 58) Buchenwald concentration camp, Nazi Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Children | 1 daughter |

| Occupation | Leader of Communist party of Germany (KPD) |

| Profession | Revolutionary, politician |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1915–18 |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

| Awards |

|

Ernst Thälmann (16 April 1886 – 18 August 1944) was the leader of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) during much of the Weimar Republic. He was arrested by the Gestapo in 1933 and held in solitary confinement for eleven years, before being shot in Buchenwald on Adolf Hitler's personal orders in 1944.[1]

Contents

1 Family and early years

2 Leaving home; World War I

3 Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (KPD)

3.1 KPD vs SPD

4 Imprisonment and execution

5 Legacy

6 Writings (selection)

7 References

8 Sources

9 External links

Family and early years

Ernst Thälmann's father was Johannes Thälmann (called 'Jan'; 11 April 1857 – 31 October 1933),[2] born in Weddern in Holstein, working there as a farmworker. Thälmann's mother, Mary-Magdalene (née Kohpeiss; 8 November 1857 – 9 March 1927),[2] was born in Kirchwerder. The wedding took place in 1884 in Hamburg. There, Johannes Thälmann earned his first money as a coachman. Ernst's parents had no party affiliation; in contrast to his father, his mother was deeply religious.

Ernst Thälmann was born in Hamburg. After his birth, his parents took a pub near the Port of Hamburg.

On 4 April 1887, his sister Frieda was born (died 8 July 1967 Hamburg). In March 1892, Thälmann's[3] parents were convicted and sentenced to two years in prison, because they had bought stolen goods or had taken them for debt payment.[3][4] Thälmann and his younger sister Frieda were separated and placed for care in different families. Thälmann's parents were released early; his mother in May, and his father in October 1893. His parents' offense would be used 36 years later in the campaign against Ernst Thälmann.

From 1893 to 1900, Thälmann attended elementary school. He later described history, natural history, folklore, mathematics, gymnastics and sports as his favorite subjects. However, he did not like religion.[3] In the mid-1890s, his parents opened a vegetable, coal and wagon shop in Eilbek,[2] a suburb of Hamburg. In this business, he had to help after school. Thälmann did his schoolwork in the morning before classes started. Despite this burden, Thälmann was a good student who enjoyed learning. His desire to become a teacher or to learn a trade was not fulfilled because his parents refused to give him the necessary money. He had to continue working in his parents' business, causing much sorrow and conflict with his parents.[2] Therefore, he sought a job as an unskilled worker in the port. Here the ten-year-old Thälmann came in contact with the port workers on strike from November 1896 till February 1897, the bitter labor dispute known as the Hamburg dockworkers strike 1896/97.[3]

Leaving home; World War I

At the beginning of 1902, he left home. He first he lived in an emergency shelter, later in a basement apartment, and in 1904 he was fireman on the steam engine freight ship AMERIKA which also traveled to the USA. He was a Social Democratic Party member during 1903. On 1 February 1904, he joined the Central Union of Trade, transport and traffic workers of Germany and ascended to the chairman of the 'Department carters'. In 1913, he supported a call of Rosa Luxemburg for a mass strike as a means of action of the SPD to enforce political demands. From 1913 to 1914, he worked for a laundry as a coachman.

In January 1915, one day before he was called up for military service in World War I, he married Rosa Koch. At the beginning of 1915, he was posted to the artillery on the western front, where he stayed till the end of the war, wounded twice. He said that he participated in the following battles: Battle of Champagne (1915–1916), Battle of the Somme (1916), Second battle of the Aisne, Battle of Soissons, Battle of Cambrai (1917) (1917) and Battle of Arras (1917).[2]

Thälmann received several awards:

Iron cross second class- Hanseatic Cross

Wound Badge[2]

Towards the end of 1917, he became a member of the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD). In October 1918, Thälmann deserted together with four fellow soldiers. He did not return from home to the front. On the day of the German Revolution, 9 November 1918, he wrote in his diary on the Western Front, "...did a bunk from the Front with 4 comrades at 2 o'clock."[citation needed][5]

Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (KPD)

Ernst Thälmann on the front page of a KPD newspaper, the Saxon Workers' News, during the 1925 presidential election. The caption reads "Ernst Thälmann: the Red President!"

In Hamburg, he participated in the construction of Hamburg Workers' and Soldiers. From March 1919, he was chairman of the USPD in Hamburg and a member of the Hamburg Parliament. At the same time he worked as relief worker in the Hamburg city park, then he found a well-paying job at the employment office. He rose to Inspector.

When the USPD split over the question whether to join the Communist International (Comintern), Thälmann sided with the pro-Communist faction which in November 1920 merged with the KPD.[5] In December Thälmann was elected to the Central Committee of the KPD. In March 1921 he was fired from his job at the employment office due to his political activities. That summer Thälmann went as a representative of the KPD to the 3rd Congress of the Comintern in Moscow and met Vladimir Lenin.[6]

In June 1922, Thälmann survived an assassination attempt at his flat. Terrorists from the ultranationalist group Organisation Consul threw a hand grenade into his ground floor flat. His wife and daughter were unhurt; Thälmann himself came home only later.

Thälmann participated in and helped to organise the Hamburg Uprising of October 1923.[7] The uprising failed, and Thälmann went to underground for some time. After the death of Lenin in January 1924, Thälmann visited Moscow and for some time maintained a guard of honour at his bier. From February 1924 he was deputy chairman of the KPD and, from May, a Reichstag member. At the 5th Congress of the Comintern that summer he was elected to the Comintern executive committee and a short time later to its steering committee. In February 1925 he became chairman of the Rote Frontkämpferbund (RFB), the defence organisation of the KPD.

In October 1925 Thälmann became chairman of the KPD and that year was a candidate for the German Presidency. Thälmann's candidacy in the second round of the presidential election split the centre-left vote and ensured that the conservative Paul von Hindenburg defeated the Centre Party's Wilhelm Marx.[8] In October 1926 Thälmann supported in person the dockers' strike in his home town of Hamburg. He saw this as solidarity with the British miners' strike which had started on 1 May and had been profitable for Hamburg Docks as an alternative supplier of coal. Thälmann's argument was that this "strike-breaking" in Hamburg had to be stopped. In March, he took part in a demonstration in Berlin, where he was injured by a blow from a sword.

In 1928 during the Wittorf affair he was ousted from the party central committee for trying to cover up embezzlement by a party official who was his close friend and protégé, John Wittorf, possibly for tactical reasons. But Stalin intervened and had Thälmann reinstated, signalling the beginning of a purge and completing the "Stalinization" of the KPD.[9]

KPD vs SPD

Ernst Thälmann statue in Weimar.

Thälmann, Ernst and Thorez, Maurice – Paris-Berlin, 1932

At the 12th party congress of the KPD in June 1929 in Berlin-Wedding, Thälmann adopted a policy of confrontation with the SPD.[9] This followed the events of "Bloody May", in which 32 people were killed by the police in an attempt to suppress demonstrations which had been banned by the Interior Minister, Carl Severing, a Social Democrat.[9]

During that time, Thälmann and the KPD fought the SPD as their main political enemy, acting according to the Comintern policy which declared Social Democrats to be "social fascists".[10] By 1927, Karl Kilbom, the Comintern representative to Germany, had started to combat this ultra leftist tendency of Thälmann within the German Communist Party, but found it to be impossible when he found Stalin was against him. Another aspect of this strategy was to attempt to win over the leftist elements of the Nazi Party, especially the SA, who largely came from a working-class background and supported socialist economic policies. These guidelines on social democracy as "social fascism" remained in force until 1935 when the Comintern officially endorsed a "popular front" of socialists, liberals and conservatives against the Nazi threat. By that time, Adolf Hitler had come to power and the KPD had largely been destroyed.[7]

In March 1932, Thälmann was once again a candidate for the German Presidency, against the incumbent Paul von Hindenburg and Hitler. The KPD's slogan was "A vote for Hindenburg is a vote for Hitler; a vote for Hitler is a vote for war." Thälmann returned as a candidate in the second round of the election, as it was permitted by the German electoral law, but his vote count lessened from 4,983,000 (13.2%), in the first round, to 3,707,000 (10.2%). After the Nazis came to power in January 1933, Thälmann proposed that the SPD and KPD should organise a general strike to topple Hitler, but this was not achieved. In February 1933, a Central Committee meeting of the already banned KPD took place in Königs Wusterhausen at the "Sporthaus Ziegenhals", near Berlin, where Thälmann called for the violent overthrow of Hitler's government. Following the Reichstag fire, on 3 March he was arrested in Berlin by the police.

Imprisonment and execution

On the afternoon of 3 March 1933 Thälmann was arrested together with his personal secretary Werner Hirsch at the home of Hans and Martha Kluczynski in Berlin-Charlottenburg (Lutzow street 9, today Alt-Lietzow 11). The arrest was undertaken by eight officers of police station 121. This was preceded by a denunciation by Hermann Hilliges, garden neighbor of the Kluczynskis in Gatow.[11] In the preceding days, at least four other people had also passed on their knowledge of the connection Kluczynski-Thälmann to the police.[12] Thälmann had used the accommodation in Lutzow street for several years occasionally, and then again in January 1933.

Although it was not among the six illegal neighborhoods that the military-political apparatus of the KPD had prepared for Thälmann, it was not considered known to the police.[13] Thälmann had led a Politbüro meeting in a bar in the Lichtenberg Gudrunstraße on 27 February. On his way back he was informed by communist functionaries about the Reichstag fire, and the sudden onset of mass arrests.

After the German–Soviet Non-Aggression Pact and Germany's invasion of Poland of 1939, and despite Thälmann's loyalty to Stalin during his time leading the KPD, Moscow pragmatically removed a slogan for the 1939 International Youth Day which read in part, "Long live Comrade Thälmann!" It was replaced with what read in part, "Long live the wise foreign policy of the Soviet Union, guided by Comrade Stalin's instructions."[14]

Thälmann spent over eleven years in solitary confinement. In August 1944, he was transferred from Bautzen prison to Buchenwald concentration camp, where he was shot on 18 August.[15] His body was immediately cremated.[3] Shortly after, the Nazis claimed in an announcement that, together with Rudolf Breitscheid, Thälmann had died in an Allied bombing attack on 23 August.[16]

Legacy

The Ernst Thälmann Monument was erected 1986 in the Ernst-Thälmann-Park, Berlin

While heading the KPD, Thälmann closely aligned the German Communists with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Supporters of a more autonomous course were expelled.[citation needed]

Thälmann's tomb in Berlin

During World War I and the Weimar Republic, the KPD competed for leadership of the working class with the more moderate Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), particularly after the latter supported German involvement in the War. Thälmann and the KPD focused their attacks primarily on the SPD to prevent it from retaining power.

During the Spanish Civil War, several units of German republican volunteers (most notably the Thälmann Battalion of the International Brigades) were named in his honour.[17] During World War II, Yugoslavia's leader Josip Broz Tito organized a company of Danube Swabians and Wehrmacht defectors as the Ernst Thälmann Company to fight the Nazis.[18]

In 1935 the former town of Ostheim in Ukraine was renamed Telmanove (Donetsk Oblast).

After 1945, Thälmann, and other leading communists who had been killed, such as Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, were widely honoured in East Germany, with many schools, streets, factories, etc., named after them. Many of these names were changed after German reunification, but streets and squares named after Thälmann remain in Berlin, Hamburg, Greifswald and Frankfurt an der Oder. The East German pioneer organisation was named the Ernst Thälmann Pioneer Organisation in his memory.[19] Members pledged that "Ernst Thälmann is my role model ... I promise to learn to work and fight [struggle] as Ernst Thälmann teaches".[20]

Trường THPT Ernst Thälmann (Ernst Thälmann High School) in District 1, Ho Chi Minh City

In the 1950s, an East German film in two parts, Ernst Thälmann, was produced.[19] In 1972, Cuba named a small island, Cayo Ernesto Thaelmann, after him.[21]

In Ho Chi Minh City, the secondary school THPT Ernst Thalmann (Ten Lơ Man) was named after him.

The British Communist composer and activist Cornelius Cardew named his Thälmann Variations for piano in Thälmann's memory.

The East German weapons factory was named after Thälmann, the VEB Ernst Thälmann Waffenfabrik.

Writings (selection)

Ernst Thälmann, Der Kampf um die Gewerkschaftseinheit und die deutsche Arbeiterklasse. Referat und Schlußwort auf dem 10. Parteitag der KPD (in German), Berlin: Vereinigung Internationaler Verlagsanstalten.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Ernst Thälmann, Wedding gegen Magdeburg (revolutionärer Befreiungskampf oder kapitalistische Sklaverei) (in German), Berlin: Internationaler Arbeiter-Verlag

Ernst Thälmann, Katastrophe oder Sozialismus? Ernst Thälmanns Kampfruf gegen die Notverordnungen (in German), Berlin: Internationaler Arbeiter-Verlag

Ernst Thälmann, Ernst Thälmann und die Jugendpolitik der KPD (in German), Berlin: Verlag Junge Welt

Ernst Thälmann, An Stalin. Briefe aus dem Zuchthaus 1939 bis 1941 (in German), Berlin: Karl Dietz Verlag, ISBN 3-320-01927-9

References

^ Ernst Thälmann biography at Spartacus educational

^ abcdef Ernst Thälmann: Gekürzter Lebenslauf, aus dem Stegreif niedergelegt, stilistisch deshalb nicht ganz einwandfrei. 1935, In: Institut für Marxismus-Leninismus beim ZK der SED (Hrsg.): Ernst Thälmann: Briefe – Erinnerungen. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1986.

^ abcde Institut für Marxismus-Leninismus beim Zentralkomitee der SED (Autorenkollektiv): Ernst Thälmann. Eine Biographie. Dietz, Berlin 1980.

^ Hamburgischer Correspodent und Hamburgische Börsen-Halle, Morgenausgabe, 5. März 1892.

^ ab Branko Lazitch and Milorad Drachkovitch, "Ernst Thälmann" in Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, Palo Alto: Hoover Institution Press, 1986

^ Norman LaPorte: The Rise of Ernst Thälmann and the Hamburg Left 1921-1923, in: Ralf Hoffrogge / Norman LaPorte (eds.): Weimar Communism as Mass Movement 1918-1933, London: Lawrence & Wishart 2017, pp. 131.

^ ab Timeline of Ernst Thälmann's life (in German), at the Lebendiges Museum Online (LEMO): https://www.dhm.de/lemo/biografie/ernst-thaelmann

^ David Priestand, Red Flag: A History of Communism, New York: Grove Press, 2009

^ abc Eric D. Weitz, Creating German Communism, 1890–1990: From Popular Protests to Socialist State. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997

^ David Priestand, Red Flag: A History of Communism',' New York: Grove Press, 2009

^ Siehe Eberhard Czichon, Heinz Marohn: Thälmann. Ein Report. Berlin 2010, Band 1, S. 683.

^ Ronald Sassning: Thälmann, Wehner, Kattner, Mielke. Schwierige Wahrheiten. In: UTOPIE kreativ. Nr. 114 (April 2000), S. 362–375, S. 364 f.

^ Siehe Czichon, Marohn: Thälmann. Band 2, S. 717.

^ "Slogans of Youth Show Soviet Shift". The New York Times.

^ Notizzettel von Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer SS, von einer Besprechung mit Adolf Hitler in der Wolfsschanze, 14. August 1944 im Ausstellungskasten 4/31 in der ehemaligen Effektenkammer des KZ Buchenwald: "12. Thälmann ist zu exekutieren".

^ Reiner Orth: Walter Hummelsheim und der Widerstand gegen den Nationalsozialismus. In: Landkreis Bernkastel-Wittlich: Kreisjahrbuch Bernkastel-Wittlich für das Jahr 2011. 2010, p. 336.

^ Eric D. Weitz, Creating German Communism, 1890–1990: From Popular Protests to Socialist State. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997

^ Lyon, P.D. (2008) After Empire: Ethnic Germans And Minority Nationalism In Interwar Yugoslavia (PhD Dissertation), University of Maryland, 2008.

^ ab Nils Hoffmann. "Jung Pioniere und FDJ – DDR-Museum-Steinhude". ddr-museum-steinhude.de.

^ Monteath, Peter (2000), Ernst Thälmann; Volume 52 of German Monitor, Rodopi, p. 142, ISBN 9789042013131

^ Sanchez, Juan Reinaldo (10 May 2015). "Inside Fidel Castro's luxurious life on his secret island getaway". New York Post. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

Sources

Biography of Ernst Thälmann on the website of the Deutsches Historisches Museum (in German)

Lemmons, Russel (2013). Hitler's Rival: Ernst Thälmann in Myth and Memory. The University Press of Kentucky.

- Timeline of Ernst Thälmann's life (in German), at the Lebendiges Museum Online (LEMO): https://www.dhm.de/lemo/biografie/ernst-thaelmann

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ernst Thälmann |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ernst Thälmann. |

Ernst Thälmann at Encyclopædia Britannica

Discourses and writings by and about Ernst Thälmann, on the Marxists Internet Archive. (in German)

Ernst Thälmann Memorial in Hamburg, Germany (in German)

- German song about Ernst Thälmann with DDR film footage

Newspaper clippings about Ernst Thälmann in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)