Andy Kaufman

Andy Kaufman | |

|---|---|

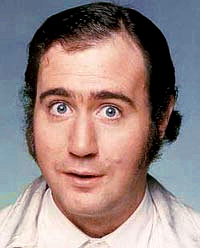

Kaufman circa 1980 | |

| Born | Andrew Geoffrey Kaufman (1949-01-17)January 17, 1949 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | May 16, 1984(1984-05-16) (aged 35) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Large cell carcinoma |

| Resting place | Beth David Cemetery, Elmont, New York |

| Occupation | Actor, performance artist, comedian |

| Years active | 1971–1984 |

| Known for | Latka Gravas in Taxi (1978–1983) |

| Style | Anti-humor, cringe humor, character comedy, surreal comedy, improvisational comedy |

| Partner(s) | Lynne Margulies (1983/84–1984; his death) |

| Children | 1 |

Andrew Geoffrey Kaufman (/ˈkaʊfmən/;[1] January 17, 1949 – May 16, 1984)[2] was an American entertainer, actor, writer, and performance artist. While often called a comedian, Kaufman described himself instead as a "song and dance man".[3] He disdained telling jokes and engaging in comedy as it was traditionally understood, once saying in a rare introspective interview, "I am not a comic, I have never told a joke. ... The comedian's promise is that he will go out there and make you laugh with him... My only promise is that I will try to entertain you as best I can."[4]

After working in small comedy clubs in the early 1970s, Kaufman came to the attention of a wider audience in 1975, when he was invited to perform portions of his act on the first season of Saturday Night Live. His Foreign Man character was the basis of his performance as Latka Gravas on the hit television show Taxi from 1978 until 1983.[5] During this time, he continued to tour comedy clubs and theaters in a series of unique performance art / comedy shows, sometimes appearing as himself and sometimes as obnoxiously rude lounge singer Tony Clifton. He was also a frequent guest on sketch comedy and late-night talk shows, particularly Late Night with David Letterman.[6] In 1982, Kaufman brought his professional wrestling villain act to Letterman's show by way of a staged encounter with Jerry "The King" Lawler of the Continental Wrestling Association (although the fact that the altercation was planned in advance was not publicly disclosed for over a decade).

Kaufman died of lung cancer in 1984, at the age of 35.[7] Because pranks and elaborate ruses were major elements of his career, persistent rumors have circulated that Kaufman faked his own death as a grand hoax.[6][8] He continues to be respected for the variety of his characters, his uniquely counterintuitive approach to comedy, and his willingness to provoke negative and confused reactions from audiences.[6][9]

Contents

1 Early life

2 Influences

3 Career

3.1 Foreign Man and Mighty Mouse

3.2 Latka

3.3 Tony Clifton

3.4 Carnegie Hall show

3.5 TV specials

3.6 Fridays incidents

3.7 Professional wrestling

3.8 Appearances

4 Personal life

5 Illness and death

5.1 Death-hoax rumors

6 Legacy and tributes

7 Filmography

7.1 Television

7.2 Film

8 Bibliography

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

Early life

Kaufman was born on January 17, 1949, in New York City, the oldest of three children. His mother was Janice (née Bernstein), a homemaker and former fashion model, and his father was Stanley Kaufman, a jewelry salesman.[10] Andy, along with his younger brother Michael and sister Carol, grew up in a middle-class Jewish family in Great Neck, Long Island.[11] He began performing at children's birthday parties at age 9, playing records and showing cartoons.[12] Kaufman spent much of his youth writing poetry and stories, including an unpublished novel, The Hollering Mangoo, which he completed at age 16.[13] Following a visit to his school from Nigerian musician Babatunde Olatunji, Kaufman began playing the congas.[14]

After graduating from Great Neck North High School in 1967, Kaufman took a year off before enrolling at the now defunct two-year Grahm Junior College[15] in Boston,[16] where he studied television production and starred in his own campus television show, Uncle Andy's Fun House.[5] In August 1969, he hitchhiked to Las Vegas to meet Elvis Presley, showing up unannounced at the International Hotel. Soon after, he began performing at coffee houses and developing his act, as well as writing a one-man play, Gosh (later renamed God and published in 2000).[16] After graduating in 1971, he began performing stand-up comedy at various small clubs on the East Coast.[17][18]

Influences

Jim Knipfel and Mark Evanier claim that Kaufman was inspired by Dick Shawn.[19][20][21][22][23]

Career

Foreign Man and Mighty Mouse

Kaufman first received major attention for his character Foreign Man, who spoke in a meek, high-pitched, heavy-accented voice and claimed to be from "Caspiar", a fictional island in the Caspian Sea.[18] It was as this character that Kaufman convinced the owner of the famed New York City comedy club The Improv, Budd Friedman, to allow him to perform on stage.[24][25]

As Foreign Man, Kaufman would appear on the stage of comedy clubs, play a recording of the theme from the Mighty Mouse cartoon show while standing perfectly still, and lip-sync only the line "Here I come to save the day" with great enthusiasm.[26] He would proceed to tell a few (purposely poor) jokes and conclude his act with a series of celebrity impersonations, with the comedy arising from the character's obvious ineptitude at impersonation. For example, in his fake accent Kaufman would say to the audience, "I would like to imitate Meester Carter, de president of de United States" and then, in exactly the same voice, say "Hello, I am Meester Carter, de president of de United States. T'ank you veddy much."

At some point in the performance, usually when the audience was conditioned to Foreign Man's inability to perform a single convincing impression, Foreign Man would announce, "And now I would like to imitate the Elvis Presley", turn around, take off his jacket, slick his hair back, and launch into a rousing, hip-shaking, excellent rendition of Presley singing one of his hit songs. Like Presley, he would take off his leather jacket during the song and throw it into the audience, but unlike Presley, Foreign Man would immediately ask for it to be returned. After the song's finale, he would take a simple bow and say in his Foreign Man voice, "T'ank you veddy much."[citation needed]

Portions of Kaufman's Foreign Man act were broadcast in the first season of Saturday Night Live. The Mighty Mouse number was featured in the October 11, 1975, premiere, while the joke-telling and celebrity impressions (including Elvis) were included in the November 8 broadcast that same year.[27]

Latka

Kaufman's well-known Foreign Man persona was later adapted as the character Latka Gravas on ABC sitcom Taxi. Though Kaufman's performances on Taxi were widely praised, even receiving two Golden Globe nominations, he was unhappy about being so closely identified with Latka.

Kaufman first used his Foreign Man character in nightclubs in the early 1970s, often to tell jokes incorrectly and do weak imitations of famous people before bursting into his Elvis Presley imitation. The character was then changed into Latka Gravas for ABC's sitcom Taxi, appearing in 79 of 114 episodes in 1978-83.[citation needed]Bob Zmuda confirms this: "They basically were buying Andy's Foreign Man character for the Taxi character Latka."[28] Kaufman's longtime manager George Shapiro encouraged him to take the gig.

Kaufman disliked sitcoms and was not happy with the idea of being in one, but Shapiro convinced him that it would quickly lead to stardom, which would earn him money he could then put into his own act. Kaufman agreed to appear in 14 episodes per season, and initially wanted four for Kaufman's alter ego Tony Clifton. After Kaufman deliberately sabotaged Clifton's appearance on the show, however, that part of his contract was dropped.[7]

His character was given multiple personality disorder, which allowed Kaufman to randomly portray other characters. In one episode of Taxi, Kaufman's character came down with a condition that made him act like Alex Reiger, the main character played by Judd Hirsch. Another such recurring character played by Kaufman was the womanizing Vic Ferrari.[29]

Sam Simon, who early in his career was a writer and later showrunner for Taxi, stated in a 2013 interview on Marc Maron's WTF podcast that the story of Kaufman having been generally disruptive on the show was "a complete fiction" largely created by Zmuda. Simon maintained that Zmuda has a vested interest in promoting an out-of-control image of Kaufman. In the interview Simon stated that Kaufman was "completely professional" and that he "told you Tony Clifton was him", but he also conceded that Kaufman would have "loved" Zmuda's version of events.[30]

Kaufman was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor in a Series, Limited Series, or Motion Picture Made For Television for Taxi in 1979 and 1981.[31]

Tony Clifton

Another well-known Kaufman character is Tony Clifton, an absurd, audience-abusing lounge singer who began opening for Kaufman at comedy clubs and eventually even performed concerts on his own around the country. Sometimes it was Kaufman performing as Clifton, sometimes it was his brother Michael or Zmuda. For a brief time, it was unclear to some that Clifton was not a real person. News programs interviewed Clifton as Kaufman's opening act, with the mood turning ugly whenever Kaufman's name came up. Kaufman, Clifton insisted, was attempting to ruin Clifton's "good name" in order to make money and become famous.

As a requirement for Kaufman's accepting the offer to star on Taxi, he insisted that Clifton be hired for a guest role on the show as if he were a real person, not a character.[7] After throwing a tantrum on the set, Clifton was fired and escorted from the studio lot by security guards. Much to Kaufman's delight, this incident was reported in the local newspapers.[32]

Carnegie Hall show

At the beginning of an April 1979 performance at New York's Carnegie Hall, Kaufman invited his "grandmother" to watch the show from a chair he had placed at the side of the stage. At the end of the show, she stood up, took her mask off and revealed to the audience that she was actually comedian Robin Williams in disguise.[33]

Kaufman also had an elderly woman (Eleanor Cody Gould) pretend to have a heart attack and die on stage, at which point he reappeared on stage wearing a Native American headdress and performed a dance over her body, "reviving" her.[34][35]

The performance is most famous for Kaufman's ending the show by actually taking the entire audience, in 24 buses, out for milk and cookies. He invited anyone interested to meet him on the Staten Island Ferry the next morning, where the show continued.[36]

TV specials

The Taxi deal with ABC included giving Kaufman a television special/pilot. He came up with Andy's Funhouse, based on an old routine he had developed while in junior college. The special was taped in 1977 but did not air until August 1979. It featured most of Andy's famous gags, including Foreign Man/Latka and his Elvis Presley impersonation, as well as a host of unique segments (including a special appearance by children's television character Howdy Doody and the "Has-been Corner").[37] There was also a segment that included fake television screen static as part of the gag, which ABC executives were not comfortable with, fearing that viewers would mistake the static for broadcast problems and would change the channel—which was the comic element Kaufman wanted to present.[38]Andy's Funhouse was written by Kaufman, Zmuda, and Mel Sherer, with music by Kaufman.[39]

In March 1980, Kaufman filmed a short segment for an ABC show called Buckshot. The segment was just over six minutes long and was called Uncle Andy's Funhouse. It featured Kaufman as the host of a children's show for adults, complete with a peanut gallery and Tony Clifton puppet.[40]

In 1983, a show very similar to Andy's Funhouse and Uncle Andy's Funhouse was filmed for PBS's SoundStage program, called The Andy Kaufman Show. It too featured a peanut gallery, and opened in the middle of an interview Kaufman is doing in which he is laughing hysterically. He then proceeds to thank the audience for watching and the credits roll.[citation needed]

Fridays incidents

In 1981 Kaufman made three appearances on Fridays, a variety show on ABC that was similar to Saturday Night Live. In his first appearance, during a sketch about four people out on a dinner date who excuse themselves to the restroom to smoke marijuana, Kaufman broke character and refused to say his lines.[41]

In response, cast member Michael Richards walked off camera and returned with a set of cue cards and dumped them on the table in front of Kaufman who responded by splashing Richards with water. Co-producer Jack Burns stormed onto the stage, leading to a brawl on camera before the show abruptly cut away to a commercial.[42]

Richards has claimed that this incident was a staged practical joke that was known only to him, associate producer Burns, and Kaufman,[43] but Melanie Chartoff, who played Kaufman's wife in the sketch, has stated that, just before airtime, Burns told her, Maryedith Burrell, and Richards that Kaufman was going to break the fourth wall.[44]

Kaufman appeared the following week in a videotaped apology to the home viewers. Later that year, Kaufman returned to host Fridays. At one point in the show, he invited a Lawrence Welk Show gospel and standards singer, Kathie Sullivan, on stage to sing a few gospel songs with him and announced that the two were engaged to be married, then talked to the audience about his newfound faith in Jesus (Kaufman was Jewish). That was also a hoax.[45] Later, following a sketch about a drug-abusing pharmacist, Kaufman was supposed to introduce the band The Pretenders. Instead of introducing the band, he delivered a nervous speech about the harmfulness of drugs while the band stood behind him ready to play. After his speech, he informed the audience that he had talked for too long and had to go to a commercial.[citation needed]

Professional wrestling

Inspired by the theatricality of kayfabe, the staged nature of the sport, and his own tendency to form elaborate hoaxes, Kaufman began wrestling women during his act and proclaimed himself "Inter-Gender Wrestling Champion of the World", taking on an aggressive and ridiculous personality based on the characters invented by professional wrestlers. He offered a $1,000 prize to any woman who could pin him.[46][47] He employed performance artist Laurie Anderson, a friend of his, in this act for a while.[48]

Kaufman initially approached the head of the World Wrestling Federation (WWF), Vince McMahon Sr., about bringing his act to the New York wrestling territory.[49] McMahon dismissed Kaufman's idea as the elder McMahon was not about to bring "show business" into his Pro Wrestling society.[49] Kaufman had by then developed a friendship with wrestling reporter/photographer Bill Apter.[49] After many discussions about Kaufman's desire to be in the pro wrestling business, Apter called Memphis wrestling icon Jerry "The King" Lawler and introduced him to Kaufman by telephone.[49]

Kaufman finally stepped into the ring (in the Memphis wrestling circuit) with a man—Lawler himself.[26] Kaufman taunted the residents of Memphis by playing "videos showing residents how to use soap" and proclaiming the city to be "the nation's redneck capital".[26] The ongoing Lawler-Kaufman feud, which often featured Jimmy Hart and other heels in Kaufman's corner, included a number of staged "works", such as a broken neck for Kaufman as a result of Lawler's piledriver and a famous on-air fight on a 1982 episode of Late Night with David Letterman.[50][51]

For some time after that first match, Kaufman appeared wearing a neck brace,[26] insisting that his injuries were much worse than they really were. Kaufman would continue to defend the Inter-Gender Championship in the Mid-South Coliseum and offered an extra prize, other than the $1,000: that if he were pinned, the woman who pinned him would get to marry him and that Kaufman would also shave his head.[52]

Eventually it was revealed that the feud and wrestling matches were staged works,[53] and that Kaufman and Lawler were friends. This was not disclosed until more than 10 years after Kaufman's death, when the Emmy-nominated documentary A Comedy Salute to Andy Kaufman aired on NBC in 1995. Jim Carrey, who revealed the secret, later went on to play Kaufman in the 1999 film Man on the Moon. In a 1997 interview with the Memphis Flyer, Lawler said he had improvised during their first match and the Letterman incident.

Although officials at St. Francis Hospital stated that Kaufman's neck injuries were real, in his 2002 biography It's Good to Be the King ... Sometimes, Lawler detailed how they came up with the angle and kept it quiet. Even though Kaufman's injury was legitimate, the pair exaggerated it. He also said that Kaufman's furious tirade and performance on Letterman was Kaufman's own idea, including when Lawler slapped Kaufman out of his chair. Promoter Jerry Jarrett later recalled that for two years, he would mail Kaufman payments comparable to what other main-event wrestlers were getting at the time, but Kaufman never deposited the checks.[54]

Kaufman appeared in the 1983 film My Breakfast with Blassie with professional wrestling personality "Classy" Freddie Blassie. The film was a parody of the art film My Dinner with Andre. Lynne Margulies, sister of the film's director, Johnny Legend, appears in it, and became romantically involved with Kaufman.

In 2002, Kaufman became a playable character in the video game Legends of Wrestling II and a standard character in 2004's Showdown: Legends of Wrestling. In 2008, Jakks Pacific produced for their WWE Classic Superstars toy line an action figure two-pack of Kaufman and Lawler, as well as a separate figures release for each of them.[citation needed]

Appearances

Although Kaufman made a name for himself as a guest on NBC's Saturday Night Live, his first prime-time appearances were several guest spots as the "Foreign Man" on the Dick Van Dyke variety show Van Dyke and Company in 1976.[55] He appeared four times on The Tonight Show in 1976–78, and three times on The Midnight Special in 1972, 1977, and 1981.[56] Kaufman appeared on The Dating Game in 1978, in character as Foreign Man, and cried when the bachelorette chose Bachelor #1, protesting that he had answered all the questions correctly.[57]

His SNL appearances started with the first show, on October 11, 1975. He made 16 SNL appearances in all, doing routines from his comedy act, such as the Mighty Mouse singalong, Foreign Man, and the Elvis impersonation. After he angered the audience with his female-wrestling routine, Kaufman in January 1983 made a pretaped appearance (his 16th) asking the audience if he should ever appear on the show again, saying he would honor their decision. SNL ran a phone vote, and 195,544 people voted to "Dump Andy" while 169,186 people voted to "Keep Andy".[58]

During the SNL episode with the phone poll, many of the cast members stated their admiration for Kaufman's work. After Eddie Murphy read both numbers, he said, "Now, Andy Kaufman is a friend of mine. Keep that in mind when you call. I don't want to have to punch nobody in America in the face", and Mary Gross read the Dump Andy phone number at a rate so fast that audiences were unable to catch it. The final tally was read by Gary Kroeger to a cheering audience. As the credits rolled, announcer Don Pardo said, "This is Don Pardo saying, 'I voted for Andy Kaufman.'"[59]

Kaufman made a number of appearances on the daytime edition of The David Letterman Show in 1980, and 11 appearances on Late Night with David Letterman in 1982-83. He made numerous guest spots on other television programs hosted by or starring celebrities like Johnny Cash (1979 Christmas special),[60]Dick Van Dyke,[55]Dinah Shore,[61]Rodney Dangerfield,[62]Cher,[63]Dean Martin,[64]Redd Foxx,[5]Mike Douglas,[5]Dick Clark,[65] and Joe Franklin.[66]

He appeared in his first theatrical film, God Told Me To, in 1976, in which he portrayed a murderous policeman.[67] He appeared in two other theatrical films, including the 1980 film In God We Tru$t, in which he played a televangelist,[68] and the 1981 film Heartbeeps, in which he played a robot.[69]

Laurie Anderson worked alongside Kaufman for a time in the 1970s, acting as a sort of "straight man" in a number of his Manhattan and Coney Island performances. One of these performances included getting on a ride that people stand in and get spun around. After everyone was strapped in, Kaufman would start saying how he did not want to be on the ride in a panicked tone and eventually cry. Anderson later described these performances in her 1995 album, The Ugly One with the Jewels.[70]

In 1983, Kaufman appeared on Broadway with Deborah Harry in the play Teaneck Tanzi: The Venus Flytrap.[71][72] It closed after just two performances.[73][74]

Personal life

Kaufman never married. His daughter, Maria Bellu-Colonna (born 1969), was the child of an out-of-wedlock relationship with a high-school girlfriend and was placed for adoption.[75] Bellu-Colonna learned in 1992 that she was Kaufman's daughter when she traced her biological roots by winning a petition of the State of New York for her biological mother's surname. She soon reunited with her mother, grandfather, uncle, and aunt.[76] Bellu-Colonna's daughter, Brittany, briefly appeared in Man on the Moon, playing Kaufman's sister Carol as a young child.[77]

In December 1969, Kaufman learned Transcendental Meditation at college.[78][79] According to a BBC article, he used the technique "to build confidence and take his act to comedy clubs". For the rest of his life, Kaufman meditated and performed yoga three hours a day.[80] From February to June 1971 he trained as a teacher of transcendental meditation in Majorca, Spain.[78]

Lynne Margulies, who met Kaufman during the filming of his My Breakfast With Blassie (she was in the film), was in a relationship with Kaufman from 1982 until his death in 1984.[81] Margulies later co-directed the 1989 Kaufman wrestling compilation I'm From Hollywood, and published the 2009 book Dear Andy Kaufman, I Hate Your Guts![82]

Illness and death

At Thanksgiving dinner on Long Island in November 1983, several family members openly expressed worry about Kaufman's persistent coughing. He claimed that he had been coughing for nearly a month, visited his doctor, and been told that nothing was wrong. When he returned to Los Angeles, he consulted another physician, then checked himself into Cedars-Sinai Medical Center for a series of medical tests. A few days later, he was diagnosed with large-cell carcinoma, an extremely rare type of lung cancer.

After audiences were shocked by his gaunt appearance during January 1984 performances, Kaufman acknowledged that he had an unspecified illness which he hoped to cure with natural medicine, including a diet of all fruits and vegetables, among other measures. Kaufman received palliative radiotherapy, but by then the cancer had spread from his lungs to his brain. His final public appearance was at the premiere of My Breakfast With Blassie in March 1984, where he appeared thin and sported a mohawk (radiation treatments made his hair fall out).[83] The following day, he and Lynne Margulies flew to Baguio, Philippines, where as a last resort, Kaufman received treatments of a pseudoscientific procedure called psychic surgery.

Kaufman died at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles on May 16, 1984, at the age of 35.[84][5][7]

Death-hoax rumors

Kaufman often spoke of faking his own death as a grand hoax, with rumors persisting, often fueled by sporadic appearances of Kaufman's character Tony Clifton at comedy clubs after his death.[85]

Kaufman's death certificate

"Clifton" performed a year after Kaufman's death at The Comedy Store benefit in Kaufman's honor, with members of his entourage in attendance, and during the 1990s made several appearances at Los Angeles nightclubs. Jim Carrey, who portrayed Kaufman in Man on the Moon, stated on the NBC special Comedy Salute to Andy Kaufman that the person doing the Clifton character was Bob Zmuda. Kaufman's official website states that his death was not a hoax.[86]

In 2013, responding to rumors following the appearance of an actress who claimed to be Kaufman's daughter and that he was still alive, Los Angeles County Coroner's office re-released Kaufman's death certificate to confirm he was indeed deceased and buried at Beth David Cemetery.[2][87][85][88][89]

In 2014, Zmuda and Lynne Margulies, Kaufman's girlfriend at the time of his death, coauthored Andy Kaufman: The Truth, Finally, a book claiming that Kaufman's death was indeed a prank, and that he would soon be revealing himself, as his upper limit on the "prank" was 30 years.[90]

Legacy and tributes

Comedian Elayne Boosler, who dated and lived with Kaufman and credits him with encouraging her to do comedy, wrote an article for Esquire in November 1984, in his memory.[91][92] She also dedicated her 1986 Showtime special Party of One to Kaufman.[93] An audio recording of Kaufman offering encouragement to Boosler is featured in the intro.[94]

In 1992, the band R.E.M. released the album Automatic for the People, which featured the Andy Kaufman-themed song "Man on the Moon".[95][96] The song's video also featured footage of Kaufman.[97] On March 29, 1995, NBC aired A Comedy Salute To Andy Kaufman. This special featured clips of many of Kaufman's performances, as well as commentary from some of his friends, family, and colleagues.[6]

Comedian Richard Lewis in A Comedy Salute to Andy Kaufman said of him: "No one has ever done what Andy did, and did it as well, and no one will ever. Because he did it first. So did Buster Keaton, so did Andy."[98]Carl Reiner recalled his distinction in the comedy world:

Did Andy influence comedy? No. Because nobody's doing what he did. Jim Carrey was influenced—not to do what Andy did, but to follow his own drummer. I think Andy did that for a lot of people. Follow your own drumbeat. You didn't have to go up there and say 'take my wife, please.' You could do anything that struck you as entertaining. It gave people freedom to be themselves.[99]

Reiner also said of Kaufman: "Nobody can see past the edges, where the character begins and he ends."[100]

Jim Carrey portrayed Kaufman in the 1999 biopic film Man on the Moon, directed by Miloš Forman; the film took its title from the band R.E.M.'s song of the same name. R.E.M. also did the score for the film and recorded another Kaufman tribute song, "The Great Beyond".[101] Carrey's portrayal was met with critical acclaim, earning him a Golden Globe Award for his performance. Forman named his twin sons, born in 1998, Andrew and James, after Kaufman and Carrey.[102][103] In July 2012, Kaufman's play Bohemia West was staged in Providence, Rhode Island.[104] Comedian Vernon Chatman compiled and produced Kaufman's first album, Andy and His Grandmother—via Drag City in 2013.[105]

Andy Kaufman is one of the featured celebrities in the 2005 children's book Different Like Me: My Book of Autism Heroes.[106] Actress Cindy Williams, who was good friends with Kaufman, devoted an entire chapter of her autobiography, Shirley, I Jest!: A Storied Life, to him.[107][108]The Chris Gethard Show paid homage to the Kaufman Fridays incident in a goof on an episode with comedian Brett Davis throwing water on someone's face.[109]

At The Comedy Store comedy club in Los Angeles there is a neon likeness of Kaufman on display. The club also features on their menu the "Andy Kaufman Special", which consists of "two cookies and a glass of ice cold milk".[110] The Vic Ferrari Band took its name from Kaufman's Taxi character.[111][112] According to executive producer Bill Oakley, the 1996 The Simpsons episode "Bart the Fink", in which Krusty the Clown fakes his death, was partially inspired by the rumors of Kaufman's faked death.[113]

Al Jean, co-creator of the animated series The Critic, has stated that the first season drawing of Jon Lovitz's character Jay Sherman was loosely based on Kaufman.[114]

For the 2015 Andy Kaufman Award show, Two Boots Pizza created a special Andy Kaufman pie.[115] As of 2018, they still feature a Tony Clifton pie on their menu. In 2015, a bottled fragrance called "Andy Kaufman Milk & Cookies" was created.[116][117]

German filmmaker Maren Ade stated that her 2016 film Toni Erdmann, which was nominated for the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, was partially inspired by Kaufman and Tony Clifton.[118][119][120]

Since 2004, The Andy Kaufman Award competition has been held annually as "a showcase for promising cutting-edge artists with fresh and unconventional material, for those willing to take risks with an audience, and for those who do not define themselves by the typical conventions of comedy".[121]

Filmography

Television

| Date | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| June 1972 | Kennedy at Night[78] | local Chicago show; Kaufman's first appearance as Elvis |

| June 6, 1974 | The Dean Martin Comedy World[78][122] | Kaufman's national television debut |

| June 20, 1974 | The Joe Franklin Show[78][123] | |

| October 11, 1975 | Saturday Night Live[78][124] | first episode of SNL; performed "Mighty Mouse" |

| October 25, 1975 | Saturday Night Live[78] | performed "Pop Goes The Weasel" |

| November 8, 1975 | Saturday Night Live[78] | Foreign Man |

| January 17, 1976 | Monty Hall's Variety Hour[78] | |

| February 28, 1976 | Saturday Night Live[5][78] | performed "Old MacDonald Had A Farm" |

| June 23, 1976 | The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson[78] | Steve Allen guest-hosted |

| September 20, 1976 – December 30, 1976 | Van Dyke & Company[78][125] | Kaufman appeared in 10 weekly episodes |

| January 12, 1977 | The Mike Douglas Show[5] | |

| January 15, 1977 | Saturday Night Live[78] | Foreign Man/Elvis |

| January 17, 1977 | Dinah![78] | Foreign Man |

| January 21, 1977 | The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson[78] | |

| February 7, 1977 | Dinah! | Kaufman sings "Kiss, Kiss, Kiss" |

| March 3, 1977 | The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson[78][126] | |

| March 4, 1977 | The Midnight Special | sings "I Trusted You" |

| May 30, 1977 | Stick Around[78] | pilot for sitcom (aired once); was filmed March 29, 1977 |

| 1977 | The 2nd Annual HBO Young Comedians Show | |

| August 4, 1977 | The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson | Elvis and drumming |

| August 15–19, 1977 | The Hollywood Squares[78] | Kaufman appeared on one week's worth of shows; was filmed in June 1977 |

| September 15, 1977 | The Redd Foxx Comedy Hour[78][127] | aired November 3, 1977 |

| October 15, 1977 | Saturday Night Live[78] | sings "Oklahoma", "Oh, The Cow Goes Moo", and does Elvis |

| December 10, 1977 | Saturday Night Live[78] | Foreign Man |

| January 3, 1978 | Variety '77: The Year in Entertainment[78] | plays congas, sings, dances, and attempts to levitate a woman |

| February 20, 1978 | The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson[78] | Steve Martin guest-hosted; Kaufman's last Tonight Show appearance |

| March 11, 1978 | Saturday Night Live[78] | reads The Great Gatsby |

| March 14, 1978 | Bananaz[78] | local Columbus, Ohio television show |

| April 11, 1978 | The Mike Douglas Show[5][78] | |

| September 12, 1978 – June 15, 1983 | Taxi[5][78] | production on the sitcom began on July 5, 1978; last episode was filmed February 18, 1983 |

| November 21, 1978 | The Dating Game[78] | as contestant "Baji Kimran" |

| November 29, 1978 | Dick Clark's Live Wednesday[78] | |

| February 24, 1979 | Saturday Night Live[78] | yodels |

| April 3, 1979 | Cher...And Other Fantasies[78] | |

| June 30, 1979 | The Lisa Hartman Show[128] | (the date for this special has often been incorrectly given as 1976) |

| August 20, 1979 | The Tomorrow Show[78] | Kaufman's first wrestling match with a woman on national television |

| August 28, 1979 | Good Morning America | |

| August 28, 1979 | Andy's Funhouse[78] | ABC special; originally taped July 15, 1977 |

| September 19, 1979 | Dinah![78] | drunken, egg-throwing Tony Clifton |

| October 20, 1979 | Saturday Night Live[78] | wrestles for the first time on SNL |

| November 17, 1979 | Saturday Night Live[78] | |

| November 22, 1979 | Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade[78] | |

| December 6, 1979 | A Johnny Cash Christmas[60][78] | Foreign Man/Elvis/Santa |

| December 13, 1979 | The Merv Griffin Show[78] | |

| December 22, 1979 | Saturday Night Live[78] | appears with "Nature Boy" Buddy Rogers; wrestles women |

| January 25, 1980 | The Merv Griffin Show[78] | aired January 29, 1980 |

| June 12, 1980 | Andy Kaufman at Carnegie Hall[5][78] | the April 1979 concert was broadcast on Showtime |

| July 18, 1980 | Uncle Andy's Funhouse (Buckshot segment)[40][78] | filmed March 1, 1980 |

| September 26, 1980 | The Merv Griffin Show | appeared with Marty Feldman |

| October 14, 1980 | The David Letterman Show[78] | tells Letterman he's been sleeping in doorways; Letterman abruptly cuts him off |

| October 15, 1980 | The David Letterman Show[78] | shows up disheveled; begs audience for money |

| January 23, 1981 | The Midnight Special | Hosted; performed much of his repertoire |

| February 20, 1981 | Fridays[78][129] | Kaufman hosts; the infamous fight episode |

| February 27, 1981 | Fridays[78][130] | videotaped apology from Kaufman |

| March 3–6, 1981 | Barbara Mandrell and the Mandrell Sisters[78] | was taped in March; unclear when or if Kaufman's segment aired* |

| March 25, 1981 | The Midnight Special[78] | introduces Tony Clifton |

| April 16, 1981 | The Slycraft Hour[78] | NYC cable access show with Bob Pagani |

| June 8, 1981 | The Merv Griffin Show[78] | Tony Clifton |

| August 31, 1981 | The Merv Griffin Show[78] | Tony Clifton |

| September 18, 1981 | Fridays[131][132] | Kaufman introduces his fiancé, Kathie Sullivan; they sing & he discusses his Christianity |

| October 28, 1981 | Good Morning America[78] | |

| October 29, 1981 | An Evening at the Improv[78] | hosted |

| December 11, 1981 | The Merv Griffin Show | |

| January 30, 1982 | Saturday Night Live[78] | in a sketch as Elvis |

| February 8, 1982 | 1981: The Year in Television[133] | briefly interviewed by Dick Cavett |

| February 17, 1982 | Late Night with David Letterman[78] | Kaufman's first appearance on Late Night; talks about doing Elvis after his death; wrestling talk |

| February 18, 1982 | Late Night with David Letterman[78] | Tony Clifton (thought at the time to be Kaufman; later revealed to be Zmuda) |

| March 30, 1982 | Late Night with David Letterman[78] | |

| April 1, 1982 | Late Night with David Letterman[78] | brief appearance in greenroom; promotes Lawler match |

| April 14, 1982 | Good Morning America[78] | |

| April 15, 1982 | The John Davidson Show[78] | |

| May 7, 1982 | Hour Magazine[78][134] | aired May 11, 1982; Kaufman appears with his brother and sister |

| May 15, 1982 | Saturday Night Live[78] | appears with Taxi castmates; discusses the Lawler wrestling match |

| May 17, 1982 | Late Night with David Letterman[78] | |

| June 25, 1982 | The Merv Griffin Show[135] | Orson Welles guest-hosts; Welles expresses his fondness for Taxi |

| July 28, 1982 | Late Night with David Letterman[5] | the infamous Lawler/Kaufman slap fight |

| September 17, 1982 | The Fantastic Miss Piggy Show | Tony Clifton |

| September 30, 1982 | Catch a Rising Star's 10th Anniversary[78] | filmed August 19, 1982 |

| October 23, 1982 | Saturday Night Live | Kaufman was due to appear in this episode, but was cut by producer Dick Ebersol. |

| October 30, 1982 | Saturday Night Live | Kaufman was due to appear in this episode, but was cut due to showing up late. |

| November 17, 1982 | Late Night with David Letterman[78] | dressed in turban, he sings "Rose Marie" |

| November 20, 1982 | Saturday Night Live[78][136] | Kaufman is voted off the show, 195,544 to 169,186 |

| January 7, 1983 | Late Night with David Letterman[78] | appears with his parents; calls grandmother in Florida |

| January 22, 1983 | Saturday Night Live[78] | videotape of Kaufman, thanking viewers who voted for him |

| February 23, 1983 | Late Night with David Letterman[78] | appears with Freddie Blassie; sings Jambalaya (On The Bayou) |

| May 2, 1983 | CWA Wrestling | |

| May 26, 1983 | Up Close with Tom Cottle[78] | interview |

| July 9, 1983 | CWA Wrestling | |

| July 15, 1983 | The Andy Kaufman Show[78] | PBS Soundstage |

| July 16, 1983 | CWA Wrestling | |

| July 23, 1983 | CWA Wrestling | |

| July 30, 1983 | CWA Wrestling | |

| August 6, 1983 | CWA Wrestling | |

| August 13, 1983 | CWA Wrestling | |

| September 22, 1983 | Late Night with David Letterman[78] | introduces his adopted children; does Elvis for the final time |

| November 7, 1983 | Superstars of Comedy Salute the Improv | aired February 12, 1984; does laundry, plays congas, and sings "Rock Island" from The Music Man |

| November 17, 1983 | Late Night with David Letterman[78] | plays scene from The Big Chill; brings adopted kids on again; final Letterman appearance |

| November 19, 1983 | CWA Wrestling | |

| November 29, 1983 | Rodney Dangerfield: I Can't Take It No More[78] | Filmed November 7, 1983 |

| January 26, 1984 | The Top[78] | Kaufman's final television appearance |

Film

| Date | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | God Told Me To[137] | Police Officer | |

| 1980 | In God We Tru$t[5] | Armageddon T. Thunderbird | |

| 1981 | Heartbeeps[5] | ValCom-17485 | |

| 1983 | My Breakfast with Blassie | Himself | Final film role |

| 1986 | Elayne Boosler: Party of One[94] | Archived voice | |

| 1989 | I'm from Hollywood | Himself | |

| 1999 | Man on the Moon | Archived singing |

Bibliography

Three books of Kaufman's writings have been posthumously published:

Kaufman, Andy (1999). The Huey Williams Story. Zilch Publishing. ISBN 9781930410008..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}, a novel

Kaufman, Andy (2000). God...and Other Plays. Zilch Publishing. ISBN 1930410018., the script for a one-man play Kaufman did in college

Kaufman, Andy (2000). Poetry and Stories. Zilch Publishing. ISBN 1930410034., a collection of his adolescent writings

References

^ "I-L". NLS.

^ ab "Certificate of Death, State of California: Andrew G. Kaufman". Country of Los Angeles Resigtrar-Recorder/County Clerk via TheSmokingGun.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2010. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

^ Givens, Ron (December 23, 1999). "Andy Kaufman recalled as bizarre, gifted". New York Daily News; Reading Eagle. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

^ Brennan, Sandra. "Full Biography". The New York Times. Retrieved April 9, 2012.I am not a comic, I have never told a joke. ... The comedian's promise is that he will go out there and make you laugh with him. ... My only promise is that I will try to entertain you as best I can. ... They say, 'Oh wow, Andy Kaufman, he's a really funny guy.'

^ abcdefghijklm Prial, Frank J. (May 18, 1984). "ANDY KAUFMAN, A COMEDIAN KNOWN FOR UNORTHODOX SKITS". The New York Times. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

^ abcd O'Connor, John J. (March 29, 1995). "TELEVISION REVIEW; Andy Kaufman's Beloved Antics". The New York Times. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ abcd Shales, Tom (May 23, 1984). "Kaufman's many faces made him one of a kind". The Milwaukee Journal. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

^ "Tip-off". Lakeland Ledger. March 30, 1995. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

^ Handler, David (June 9, 1984). "Kaufman Blazed New Trails". Ocala Star-Banner. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

^ Zehme. pp.6–10

^ Zehme, Bill (1999). Lost in the Funhouse: The Life and Mind of Andy Kaufman. Delacorte Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780385333719.

^ ""The Real Man on the Moon Talks" by Kaufman's father". Andykaufman.jvlnet.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2010. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

^ Zehme. pp. 67–68

^ Zehme. pp. 38–39.

^ "Grahm Junior College Alumni". Grahmjuniorcollege.org. 2017-01-03. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

^ ab "Profile: Andy Kaufman". Park City Daily News. December 30, 1979. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

^ Zehme. pp.132–141

^ ab Shepard, Richard F. (July 11, 1974). "Songs and a New Comedian Make Lively Cabaret". The New York Times. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

^ "Second Greatest - News From ME". newsfromme.com. 23 March 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

^ Knipfel, Jim. "The Humbly Great Dick Shawn". ozy.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

^ Knipfel, Jim. "Where Andy Kaufman Came From". denofgeek.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

^ Knipfel, Jim. "Slackjaw". www.electronpress.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

^ "The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson - Steve Allen (guest host), Dick Shawn, Andy Kaufman". thetvdb.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

^ "Improv Comedy Club History".

^ Zoglin, Richard (2008). Comedy at the Edge: How Stand-up in the 1970s Changed America. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 1582346240. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

^ abcd Drash, Wayne (April 7, 2012). "The Great Ruse: The comedic genius who rocked wrestling". CNN. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

^ SNL: The Complete First Season, 1975–1976. DVD recording.

^ "Andy Kaufman Oral History" Archived December 6, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, interviews with Don Steinberg, originally published in short form in GQ Magazine, December 1999.

^ Taxi (Season 3, Episode 20, "Latka the Playboy", imdb.com; accessed January 28, 2017.

^ Maron, Marc (May 16, 2013). "Episode 389 – Sam Simon", WTFPod.com; accessed January 28, 2017.

^ "Golden Globe Awards: Winners & Nominees". GoldenGlobes.com. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

^ Knoedelseder, William (2009). I'm Dying Up Here: Heartbreak and High Times in Stand-up Comedy's Golden Era. PublicAffairs. ISBN 9781586483173.

^ Maslin, Janet (April 28, 1979). "Comedy: Andy Kaufman Fills Stage With Parade of Odd Characters". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

^ Shackett, Barbara (2013). Stranded in Montana; Dumped in Arizona. Dorrance Publishing. ISBN 9781434928559. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

^ Carter, Betsy (July 1, 1979). "Hide-'n'-seek in Andy Kaufman's fun house". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

^ "Comic Encore: Milk, Cookies For Audience". The Ottawa Citizen. April 28, 1979. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ Maslin, Janet (August 28, 1979). "TV: A 90‐Minute Special With Andy Kaufman". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

^ Wickstrom, Andy (August 3, 1989). "Andy Kaufman Still Surprises in a 1977 Video". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

^ Elisberg, Robert J. (July 22, 2013). "Pal Mel". The Huffington Post. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

^ ab Arnott, Susan L. (July 18, 1980). "The Television Picture: What's Special..." The Milwaukee Journal. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

^ Schwartz, Tony (February 24, 1981). "Was 'Fight' on TV Real or Staged? It All Depends". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

^ Andy Kaufman on Fridays from FridaysFan. Funnyordie.com. February 11, 2008. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

^ "Michael Richards 'Speaking Freely' transcript" Archived August 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine; recorded February 28, 2002 in Aspen, Colorado. Firstamendmentcenter.org (February 28, 2002); retrieved October 30, 2016.

^ Chartoff, Melanie (July 28, 2007). "An Andy Kaufman Story – What really happened on that infamous episode of "Fridays"? An insider finally reveals the truth". aish.com. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

^ Burton, Alex (February 25, 2000). "Kaufman Was My Hoax Fiance; The Taxi star pulled some of the funniest stunts on US TV, but his fake engagement fooled the world". Daily Record. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

^ Rosenberg, Howard (December 21, 1979). "Corpus Christi Cosmetician Among Competitors: Woman-Wrestling Comic May Meet Match". The Victoria Advocate. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

^ "Ms. Peckham eyes rematch with Kaufman". Bangor Daily News. December 26, 1979. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

^ Laurie Anderson, Stories from the Nerve Bible (Perennial 1993)

^ abcd Johnson, Vaughn (October 21, 2015). "Bill Apter recounts legendary career in new book". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

^ "kaufman-lawler". YouTube. 2012-03-24. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

^ "Andy Kaufman in New Fray with Wrestler on TV Show". The New York Times. July 30, 1982. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

^ "The Kaufman Lawler Feud: Chapter 2 – The Fourth One". January 13, 2009.

^ Collins, Scott (November 15, 2013). "Jerry Lawler: Why his Andy Kaufman wrestling match still resonates". Los Angeles Times.

^ "(Title unknown)". Wrestling Observer Figure Four Online. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2017. (Registration required (help)).

^ ab Sharbutt, Jay (September 20, 1976). "Van Dyke springs hour of lunacy". Lawrence Journal-World. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

^ "Andy Kaufman - Comedy and Humor". Comedy and Humor. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

^ Andy Kaufman en The Dating Game (1978) (Subtitulado), 2016-04-08, retrieved 2017-11-25

^ Alan Graham (producer) (February 21, 2008). The Passion of Andy Kaufman (Archive footage). Subterranean Cinema. Event occurs at 2:20:00. Archived from the original (SWF) on October 5, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2008.

^ Alan Graham (producer) (February 21, 2008). The Passion of Andy Kaufman (Archive footage). Subterranean Cinema. Event occurs at 2:10:55–2:20:33. Archived from the original (SWF) on October 5, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2008.

^ ab "Whole Family Joins Johnny For Special". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. December 2, 1979. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

^ Sasso, Joey (November 13, 1979). "TV Ticker". The Times-News. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

^ Sherwood, Rick (November 29, 1983). "Dangerfield gets respect". Star-News. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

^ Winfrey, Lee (March 7, 1979). "Cher's picking up pieces after 2 broken marriages". The Montreal Gazette. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

^ ""Comedy World" Premieres". The Evening Independent. June 6, 1974. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

^ "Connie Francis Makes Rare Appearance". The Herald-Journal. November 25, 1978. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

^ Cattuna, Emily (February 2, 2015). "Remember When: Mourning the loss of radio and TV pioneer Joe Franklin". nj.com. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

^ Dowd, A.A. (March 14, 2014). "Larry Cohen's God is a deranged God". A.V. Club. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

^ Corry, John (September 26, 1980). "A Monk Meets Huckster and God". The New York Times. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

^ Smith, Stacy Jenel (January 2, 1982). "Andy Kaufman: His Humor is Frustrating, Strange". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

^ Stern, Amanda (January 2012). "Laurie Anderson". The Believer. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

^ Del Signore, John (November 8, 2007). "Deborah Harry, Recording Artist". Gothamist. Archived from the original on July 14, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

^ Rich, Frank (April 21, 1983). "Stage: "Teaneck Tanzi", Comedy from Britain". The New York Times. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

^ ""Teaneck Tanzi" Closes". The New York Times. April 22, 1983. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

^ Dietz, Dan (2016). The Complete Book of 1980s Broadway Musicals. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442260917. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

^ "Maria Colonna Kaufman- Taxi Actor Andy Kaufman's real daughter". Daily Entertainment News. November 15, 2013.

^ "Latka's Legacy". People. April 3, 1995.

^ "Waking Andy Kaufman". The Village Voice. November 9, 1999. Archived from the original on July 24, 2013.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabacadaeafagahaiajakalamanaoapaqarasatauavawaxayazbabbbcbdbebfbgbhbibjbkblbmbnbobpbqbrbsbtbubvbwbx "The Life and Mind of Andy Kaufman". Andykaufman.jvlnet.com. October 3, 1995. Archived from the original on January 10, 2010. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

^ Goldberg, Philip (May 15, 2014). "Remembering Andy Kaufman 30 Years on". The Huffington Post. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ "Andy Kaufman – the Song and Dance Man". BBC. October 1, 2007. Archived from the original on January 26, 2010. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

^ Brody, Richard (November 20, 2017). "The Creative Genius That Both 'Man on the Moon' and 'Jim & Andy' Missed". The New Yorker. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

^ Margulies, Lynne; Zmuda, Bob. Dear Andy Kaufman, I Hate Your Guts! (December 1, 2009, Process Publishing), a book containing the letters sent to Kaufman challenging him to wrestle.

^ Wolmuth, Roger (June 4, 1984). "Andy Kaufman 1949–1984". People. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

^ Carpenter, Les (May 16, 2004). "Squiggy is in the house: 'Laverne and Shirley' star now M's scout". The Seattle Times. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

^ ab Drash, Wayne (November 15, 2013). "Andy Kaufman's brother says he is victim of hoax". CNN. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

^ "The Last Days of Andy Kaufman". Andykaufman.jvlnet.com. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

^ "Certificate of Death: Andrew G. Kaufman" (PDF). Autopsyfiles.org. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

^ "Shocker: Andy Kaufman's "Daughter" Is Actually A New York Actress Whose Real Dad Is A Doctor". TheSmokingGun.com. November 14, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

^ Blake, Meredith. "Andy Kaufman's brother now claims he was the victim of a hoax". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

^ Getlen, Larry. "Friend: Andy Kaufman is still alive". New York Post. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

^ Boosler, Elayne (November 1984). "Andy: A farewell to Andy Kaufman by one who shared the ride". Esquire. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ McLellan, Dennis (January 28, 2000). "Boosler on Kaufman: Funny, Sweet, Bright". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ O'Connor, John J. (October 7, 1986). "2 COMEDY PROGRAMS, ON HBO AND SHOWTIME". The New York Times. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

^ ab "Andy Kaufman Quotes". Archived from the original on January 4, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

^ Evans, Paul (October 29, 1992). "Automatic for the People (Review)". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ Powers, Ann (October 11, 1992). "RECORDINGS VIEW; A Weary R.E.M. Seems Stuck in Midtempo". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

^ MacLeod, Duncan (July 18, 2009). "REM Man on the Moon Music Video". The Inspiration Room. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

^ A Comedy Salute to Andy Kaufman (TV production). NBC.

^ "Did You Hear This One About Andy? - Pop Culture Madness Network News". Pop Culture Madness Network News. 2013-11-15. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

^ Gardella, Kay (November 28, 1982) Andy Kaufman: 'Nobody can see past the edges. New York Daily News.

^ "R.E.M. To Score 'Man on the Moon'". MTV News. March 1, 1999. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ [1]

^ "The best crooner scene: Man on the moon". The Guardian. May 25, 2000. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ Scharfenberg, David (July 11, 2012). "Andy Kaufman's Bohemia West premieres in Providence". The Boston Phoenix. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

^ Itzkoff, Dave (May 10, 2013). "Album of Unreleased Andy Kaufman Material Coming in July". The New York Times. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

^ Elder, Jennifer; Thomas, Marc (2005), Different Like Me: My Book of Autism Heroes, Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

ISBN 1843108151

^ "Interview: Cindy Williams talks Laverne & Shirley, Andy Kaufman and her TV career". MeTV. October 6, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ Williams, Cindy (2015), Shirley, I Jest!: A Storied Life, Taylor Trade Publishing.

ISBN 1630760129

^ Wright, Megh. (October 23, 2014) A Rival Public Access Producer Almost Started a Brawl on The Chris Gethard Show, Splitsider.com; retrieved October 30, 2016.

^ Menu The Comedy Store West Hollywood, CA 90069, Yellowpages.com; retrieved October 30, 2016.

^ "Meet Vic Ferrari". Retrieved November 24, 2016.

^ Gast, Jon (February 17, 2015). "Gast: Vic Ferrari Band can't escape the question". Green Bay Press Gazette. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

^ Oakley, Bill (2005). The Simpsons season 7 DVD commentary for the episode "Bart the Fink" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

^ Burns, Ashley (November 29, 2016). "From Near 'Simpsons' Spinoff To A Check Against Hollywood Ridiculousness: Why 'The Critic' Still Matters". uproxx.com. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

^ "Submissions Now Being Accepted for 2015 Andy Kaufman Award". BroadwayWorld.com. September 3, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ "Xyrena Announces Official Andy Kaufman Milk & Cookies Fragrance". PR Newswire. October 7, 2015. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

^ "There's Andy Kaufman perfume, in case you wanted to smell like Andy Kaufman". Mashable.com. October 8, 2015. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

^ Dargis, Manohla (May 22, 2016). "The Director of 'Toni Erdmann' Savors Her Moment at Cannes". The New York Times. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

^ Su, Zhuo-Ning (May 19, 2016). "Maren Ade on 'Toni Erdmann,' Being Inspired By Andy Kaufman, and Finding a Dramatic Balance". thefilmstage.com. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

^ Roxborough, Scott (May 12, 2016). "Cannes: 'Toni Erdmann' Director Maren Ade Wants a Subsidy Quota for Women Filmmakers (Q&A)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

^ "The Andy Kaufman Award Website". Andykaufmanaward.org. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

^ Holsopple, Barbara (June 6, 1974). "It's Shocking How Many People Can Not Do Comedy". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

^ Brownfield, Paul (January 19, 2002). "With Strings Attached: A guitar belonging to the late Andy Kaufman is up for auction on EBay, put up by a former New York talk-show host". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

^ Hill, Doug (March 2, 1986). "First "Saturday Night Live" was a wacky close call". Sunday Star-News. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

^ "Van Dyke & Company: The Complete Series". Amazon. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

^ "Tonight on Television". Ocala Star-Banner. March 3, 1977. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

^ "T.V. Scout". The Sumter Daily Item. November 3, 1977. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

^ Harrison, Bernie (June 30, 1979). "Saturday's Highlights". The Spokesman Review. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

^ "Shoving Match No Accident". Associated Press/Observer-Reporter. February 23, 1981. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

^ "TV show continues make-believe dispute". Associated Press/Gadsden Times. February 28, 1981. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

^ "Simon, Garfunkel reunite Saturday". Wire Service Reports/Eugene Register-Guard. September 18, 1981. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

^ McLeod, Kembrew (May 11, 2012). "Atomic Andy Kaufman: The Comedian That Loved to Bomb". Little Village. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

^ "TV GUIDE SPECIAL, THE 3RD ANNUAL: 1981 – THE YEAR IN TELEVISION (TV)". The Paley Center For Media. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

^ "TV listings". St. Petersburg Times. May 11, 1982. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

^ Battaglio, Stephen (November 11, 2014). "The Biz: Revisiting The Merv Griffin Show". TV Guide. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

^ Kornbluth, Josh (May 22, 1984). "Andy Kaufman, 1949–1984". The Boston Phoenix. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

^ Pouncey, T.E. (June 22, 2008). "Conversations with GoD: Larry Cohen". Geeks of Doom. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

Further reading

- Zehme, Bill (1999), Lost in the Funhouse: The Life and Mind of Andy Kaufman, Delacorte Press.

ISBN 978-0-385-33371-9

- Zmuda, Bob; Hansen, Matthew Scott (1999), Andy Kaufman Revealed!: Best Friend Tells All, Back Bay Books.

ISBN 0-316-61098-4

- Hecht, Julie (2001), Was This Man a Genius? Talks with Andy Kaufman, Vintage Books.

ISBN 0-375-50457-5

- Keller, Florian (2005), Andy Kaufman: Wrestling with the American Dream, University Of Minnesota Press.

ISBN 0816646031

- Zoglin, Richard (2008), Comedy at the Edge: How Stand-up in the 1970s Changed America, Bloomsbury USA.

ISBN 1582346240

- Margulies, Lynne; Zmuda, Bob (2009), Dear Andy Kaufman, I Hate Your Guts!, Process.

ISBN 1934170089

- Knoedelseder, William (2009), I'm Dying Up Here: Heartbreak and High Times in Stand-Up Comedy's Golden Era, PublicAffairs.

ISBN 158648317X

- Margulies, Lynne; Zmuda, Bob (2014), Andy Kaufman, The Truth Finally, BenBella Books.

ISBN 9781940363059

External links

Andy Kaufman at Curlie

Andy Kaufman on IMDb