La Gomera

Flag | |

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Atlantic Ocean |

| Coordinates | 28°07′N 17°13′W / 28.117°N 17.217°W / 28.117; -17.217 |

| Archipelago | Canary Islands |

| Area | 369.76 km2 (142.77 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,487 m (4,879 ft) |

| Highest point | Garajonay |

| Administration | |

Spain | |

| Autonomous Community | Canary Islands |

| Province | Santa Cruz de Tenerife |

| Capital and largest city | San Sebastián de la Gomera (pop. 8451) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 21,136 (2018) |

| Pop. density | 59 /km2 (153 /sq mi) |

Volcanic valley of La Gomera

Volcanic plugs in the centre of La Gomera

Laurisilva of Garajonay, in La Gomera.

Los Órganos, La Gomera.

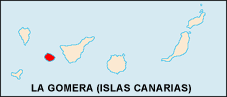

La Gomera (pronounced [la ɣoˈmeɾa]) is one of Spain's Canary Islands, located in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Africa. With an area of 369.76 square kilometers, it is the second smallest of the seven main islands of this group. It belongs to the province of Santa Cruz de Tenerife. La Gomera is the second least populous island with 21,136 inhabitants.[1] Its capital is San Sebastián de La Gomera, where the headquarters of the Cabildo are located.

Contents

1 Political organisation

2 Geography

3 Ecology

4 Natural symbols

5 Culture

6 Genetics

7 Festivals

8 Notable natives and residents

9 References

10 External links

Political organisation

La Gomera is part of the province of Santa Cruz de Tenerife. It is divided into six municipalities:

- Agulo

- Alajeró

- San Sebastián de La Gomera

- Hermigua

- Valle Gran Rey

- Vallehermoso

The island government (cabildo insular) is located in the capital, San Sebastián.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin and roughly circular; it is about 22 kilometres (14 miles) in diameter. The island is very mountainous and steeply sloping and rises to 1,487 metres (4,879 ft) at the island's highest peak, Alto de Garajonay. Its shape is rather like an orange that has been cut in half and then split into segments, which has left deep ravines or barrancos between them.

Ecology

The uppermost slopes of these barrancos, in turn, are covered by the laurisilva - or laurel rain forest, where up to 50 inches of precipitation fall each year.

The upper reaches of this densely wooded region are almost permanently shrouded in clouds and mist, and as a result are covered in lush and diverse vegetation: they form the protected environment of Spain's Garajonay National Park, which was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1986. The slopes are criss-crossed by paths that present varying levels of difficulty to visitors, and stunning views to seasoned hikers.

The central mountains catch the moisture from the trade wind clouds and yield a dense jungle climate in the cooler air, which contrasts with the warmer, sun-baked cliffs near sea level.

Between these extremes one finds a fascinating gamut of microclimates; for centuries, the inhabitants of La Gomera have farmed the lower levels by channelling runoff water to irrigate their vineyards, orchards and banana groves.

Natural symbols

The official natural symbols associated with La Gomera are Columba junoniae (Paloma rabiche) and Persea indica (Viñátigo).[2]

Columba junoniae

Persea indica

Culture

The local wine is distinctive and often accompanied with a tapa (snack) of local cheese, roasted pork, or goat meat. Other culinary specialities include almogrote, a cheese spread, miel de palma, a syrup extracted from palm trees, and "escaldón", a porridge made with gofio flour.

The inhabitants of La Gomera have an ancient way of communicating across deep ravines by means of a whistled speech called Silbo Gomero, which can be heard 2 miles away.[3] This whistled language is indigenous to the island, and its existence has been documented since Roman times. Invented by the original inhabitants of the island, the Guanches, Silbo Gomero was adopted by the Spanish settlers in the 16th century and survived after the Guanches were entirely assimilated.[3] When this means of communication was threatened with extinction at the dawn of the 21st century, the local government required all children to learn it in school. Marcial Morera, a linguist at the University of La Laguna has said that the study of silbo may help understand how languages are formed.[3]

In the mountains of La Gomera, its original inhabitants worshipped their god, whom they called Orahan; the summit and centre of the island served as their grand sanctuary. Indeed, many of the natives took refuge in this sacred territory in 1489, as they faced imminent defeat at the hands of the Spaniards, and it was here that the conquest of La Gomera was drawn to a close. Modern-day archaeologists have found several ceremonial stone constructions here that appear to represent sacrificial altar stones, slate hollows, or cavities. It was here that the Guanches built pyres upon which to make offerings of goats and sheep to their god. This same god, Orahan, was known on La Palma as Abora and on Tenerife and Gran Canaria as Arocan. The Guanches also interred their dead in caves. Today, saints, who are worshipped through village festivals, are principally connected with Christianity. But in some aspects, the Guanches’ god-like idealising of Gomeran uniqueness plays a role as well besides their pre-Christian and pre-colonial implication and shows strong local differences.[4]

Christopher Columbus made La Gomera his last port of call before crossing the Atlantic in 1492 with his three ships. He stopped here to replenish his crew's food and water supplies, intending to stay only four days. Beatriz de Bobadilla y Ossorio, the Countess of La Gomera and widow of Hernán Peraza the Younger, offered him vital support in preparations of the fleet, and he ended up staying one month. When he finally set sail on 6 September 1492, she gave him cuttings of sugarcane, which became the first to reach the New World. After his first voyage of Discovery, Columbus again provisioned his ships at the port of San Sebastián de La Gomera in 1493 on his second voyage to the New World, commanding a fleet of 17 vessels. He visited La Gomera for the last time in 1498 on his third voyage to the Americas. The house in San Sebastián in which he is reputed to have stayed is now a tourist attraction.

Genetics

An autosomal study in 2011 found an average Northwest African influence of about 17% in Canary Islanders with a wide interindividual variation ranging from 0% to 96%. According to the authors, the substantial Northwest African ancestry found for Canary Islanders supports that, despite the aggressive conquest by the Spanish in the 15th century and the subsequent immigration, genetic footprints of the first settlers of the Canary Islands persist in the current inhabitants. Parallelling mtDNA findings (50.1% of U6 and 10.83% of L haplogroups),[5] the largest average Northwest African contribution (42.50%) was found for the samples from La Gomera.[6] According to Flores et al. (2003), genetic drift could be responsible for the contrasting difference in Northwest African ancestry detected with maternal (51% of Northwest African lineages) and paternal markers (0.3–10% of Northwest African lineages) in La Gomera. Alternatively, it could reflect the dramatic way the island was conquered, producing the strongest sexual asymmetry in the archipelago.[7]

Festivals

Virgin of Guadalupe, patron saint of the island of La Gomera.

The festival of the Virgin of Guadalupe, patron saint of the island, is the Monday following the first Saturday of October.

Every five years (most recently in 2013) is celebrated the Bajada de la Virgen de Guadalupe (the Bringing the Virgin) from her hermitage in Puntallana to the capital. She is brought by boat to the beach of San Sebastián de La Gomera, where several people host her, and transported throughout the island for two months.

Notable natives and residents

Antonio José Ruiz de Padrón (1757–1823), Franciscan priest and politician.

José Aguiar (1895–1975), painter.

Pedro García Cabrera (1905–1981), writer and poet.

Tim Hart (1948–2009), English folk musician.

Manuel Mora Morales (born 1952), writer, filmmaker and editor.

Oliver Weber (born 1970), German photographer, physician and professor of visual arts.

References

^ Population referred to the January 1, 2018 Archived 1 January 2019 at boe.es [Error: unknown archive URL]

^ Ley 7/1991, de 30 de abril, de símbolos de la naturaleza para las Islas Canarias

^ abc Laura Plitt (11 January 2013). "Silbo gomero: A whistling language revived". BBC News. Retrieved 13 January 2013..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Jaehnichen, G. (2011). Steps into the future: San Isitdro's procession dance. In: Jaehnichen & Chieng, (eds.) Preserving creativity in music practice. Universiti Putra Malaysia Press.http://www.mercado-mallorca.com/canaries.htm 2012

^ Fregel et al.(2009) The maternal aborigine colonization of La Palma (Canary Islands) Euro J Hum Gen 17:1314-1324

^ Pino-Yanes M, Corrales A, Basaldúa S, Hernández A, Guerra L, et al. 2011 North African Influences and Potential Bias in Case-Control Association Studies in the Spanish Population. PLoS ONE 6(3): e18389. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018389

^ Flores, C., Maca-Meyer, N., Pérez, J. A., González, A. M., Larruga, J. M. & Cabrera, V. M. 2003 A predominant European ancestry of paternal lineages from Canary Islands. Ann Hum Genet 67, 138–152. doi:10.1046/j.1469-1809.2003.00015.x

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to La Gomera. |

La Gomera travel guide from Wikivoyage

La Gomera travel guide from Wikivoyage- Cabildo de La Gomera

- La Gomera - Official Canary Islands Tourism

Coordinates: 28°07′N 17°13′W / 28.117°N 17.217°W / 28.117; -17.217