United Nations Security Council

| |

UN Security Council Chamber in New York City | |

| Abbreviation | UNSC |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1945 |

| Type | Principal Organ |

| Legal status | Active |

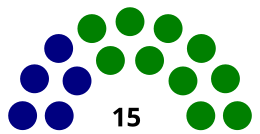

Membership | 15 states

|

Head | President François Delattre |

| Website | un.org/en/sc |

Permanent members (5) | |

| United Nations System |

|---|

|

Principal Organs |

United Nations Secretariat |

United Nations General Assembly |

International Court of Justice |

United Nations Security Council |

United Nations Economic and Social Council |

United Nations Trusteeship Council |

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN),[1] charged with the maintenance of international peace and security[2] as well as accepting new members to the United Nations[3] and approving any changes to its United Nations Charter.[4] Its powers include the establishment of peacekeeping operations, the establishment of international sanctions, and the authorization of military action through Security Council resolutions; it is the only UN body with the authority to issue binding resolutions to member states. The Security Council held its first session on 17 January 1946.

Like the UN as a whole, the Security Council was created following World War II to address the failings of a previous international organization, the League of Nations, in maintaining world peace. In its early decades, the Security Council was largely paralyzed by the Cold War division between the US and USSR and their respective allies, though it authorized interventions in the Korean War and the Congo Crisis and peacekeeping missions in the Suez Crisis, Cyprus, and West New Guinea. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, UN peacekeeping efforts increased dramatically in scale, and the Security Council authorized major military and peacekeeping missions in Kuwait, Namibia, Cambodia, Bosnia, Rwanda, Somalia, Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The Security Council consists of fifteen members.[5] The great powers that were the victors of World War II—the Soviet Union (now represented by Russia), the United Kingdom, France, China, and the United States—serve as the body's five permanent members. These permanent members can veto any substantive Security Council resolution, including those on the admission of new member states or candidates for Secretary-General. The Security Council also has 10 non-permanent members, elected on a regional basis to serve two-year terms. The body's presidency rotates monthly among its members.

Security Council resolutions are typically enforced by UN peacekeepers, military forces voluntarily provided by member states and funded independently of the main UN budget. As of 2016[update], 103,510 peacekeepers and 16,471 civilians were deployed on sixteen peacekeeping operations and one special political mission.[6]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Background and creation

1.2 Cold War

1.3 Post-Cold War

2 Role

3 Members

3.1 Permanent members

3.1.1 Veto power

3.2 Non-permanent members

3.3 President

4 Meeting locations

4.1 Consultation room

5 Subsidiary organs/bodies

6 United Nations peacekeepers

7 Criticism and evaluations

8 Membership reform

9 See also

10 Notes

11 References

11.1 Citations

11.2 Sources

12 Further reading

13 External links

History

Background and creation

In the century prior to the UN's creation, several international treaty organizations and conferences had been formed to regulate conflicts between nations, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907.[7] Following the catastrophic loss of life in World War I, the Paris Peace Conference established the League of Nations to maintain harmony between the nations.[8] This organization successfully resolved some territorial disputes and created international structures for areas such as postal mail, aviation, and opium control, some of which would later be absorbed into the UN.[9] However, the League lacked representation for colonial peoples (then half the world's population) and significant participation from several major powers, including the US, USSR, Germany, and Japan; it failed to act against the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria, the Second Italo-Ethiopian War in 1935, the 1937 Japanese occupation of China, and Nazi expansions under Adolf Hitler that escalated into World War II.[10]

Chiang Kai-shek, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill met at the Cairo Conference in 1943 during World War II.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Soviet general secretary Joseph Stalin at the Yalta Conference, February 1945

The earliest concrete plan for a new world organization began under the aegis of the US State Department in 1939.[11] Roosevelt first coined the term United Nations to describe the Allied countries."On New Year's Day 1942, President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Churchill, Maxim Litvinov, of the USSR, and T. V. Soong, of China, signed a short document which later came to be known as the United Nations Declaration and the next day the representatives of twenty-two other nations added their signatures."[12] The term United Nations was first officially used when 26 governments signed this Declaration. By 1 March 1945, 21 additional states had signed.[13] "Four Policemen" was coined to refer to the four major Allied countries: the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and China.[14] and became the foundation of an executive branch of the United Nations, the Security Council.[15]

In mid-1944, the delegations from the Allied "Big Four", the Soviet Union, the UK, the US and China, met for the Dumbarton Oaks Conference in Washington, D.C. to negotiate the UN's structure,[16] and the composition of the UN Security Council quickly became the dominant issue. France, the Republic of China, the Soviet Union, the UK, and US were selected as permanent members of the Security Council; the US attempted to add Brazil as a sixth member, but was opposed by the heads of the Soviet and British delegations.[17] The most contentious issue at Dumbarton and in successive talks proved to be the veto rights of permanent members. The Soviet delegation argued that each nation should have an absolute veto that could block matters from even being discussed, while the British argued that nations should not be able to veto resolutions on disputes to which they were a party. At the Yalta Conference of February 1945, the American, British, and Russian delegations agreed that each of the "Big Five" could veto any action by the council, but not procedural resolutions, meaning that the permanent members could not prevent debate on a resolution.[18]

On 25 April 1945, the UN Conference on International Organization began in San Francisco, attended by 50 governments and a number of non-governmental organizations involved in drafting the United Nations Charter.[19] At the conference, H. V. Evatt of the Australian delegation pushed to further restrict the veto power of Security Council permanent members.[20] Due to the fear that rejecting the strong veto would cause the conference's failure, his proposal was defeated twenty votes to ten.[21]

The UN officially came into existence on 24 October 1945 upon ratification of the Charter by the five then-permanent members of the Security Council and by a majority of the other 46 signatories.[19] On 17 January 1946, the Security Council met for the first time at Church House, Westminster, in London, United Kingdom.[22]

Cold War

Church House in London where the first Security Council Meeting took place on 17 January 1946

The Security Council was largely paralysed in its early decades by the Cold War between the US and USSR and their allies, and the Council generally was only able to intervene in unrelated conflicts.[23] (A notable exception was the 1950 Security Council resolution authorizing a US-led coalition to repel the North Korean invasion of South Korea, passed in the absence of the USSR.)[19][24] In 1956, the first UN peacekeeping force was established to end the Suez Crisis;[19] however, the UN was unable to intervene against the USSR's simultaneous invasion of Hungary following that country's revolution.[25] Cold War divisions also paralysed the Security Council's Military Staff Committee, which had been formed by Articles 45–47 of the UN Charter to oversee UN forces and create UN military bases. The committee continued to exist on paper but largely abandoned its work in the mid-1950s.[26][27]

In 1960, the UN deployed the United Nations Operation in the Congo (UNOC), the largest military force of its early decades, to restore order to the breakaway State of Katanga, restoring it to the control of the Democratic Republic of the Congo by 1964.[28] However, the Security Council found itself bypassed in favour of direct negotiations between the superpowers in some of the decade's larger conflicts, such as the Cuban missile crisis or the Vietnam War.[29] Focusing instead on smaller conflicts without an immediate Cold War connection, the Security Council deployed the United Nations Temporary Executive Authority in West New Guinea in 1962 and the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus in 1964, the latter of which would become one of the UN's longest-running peacekeeping missions.[30][31]

On 25 October 1971, over US opposition but with the support of many Third World nations, the mainland, communist People's Republic of China was given the Chinese seat on the Security Council in place of Taiwan; the vote was widely seen as a sign of waning US influence in the organization.[32] With an increasing Third World presence and the failure of UN mediation in conflicts in the Middle East, Vietnam, and Kashmir, the UN increasingly shifted its attention to its ostensibly secondary goals of economic development and cultural exchange. By the 1970s, the UN budget for social and economic development was far greater than its budget for peacekeeping.[33]

Post-Cold War

US Secretary of State Colin Powell holds a model vial of anthrax while giving a presentation to the Security Council in February 2003.

After the Cold War, the UN saw a radical expansion in its peacekeeping duties, taking on more missions in ten years' time than it had in its previous four decades.[34] Between 1988 and 2000, the number of adopted Security Council resolutions more than doubled, and the peacekeeping budget increased more than tenfold.[35] The UN negotiated an end to the Salvadoran Civil War, launched a successful peacekeeping mission in Namibia, and oversaw democratic elections in post-apartheid South Africa and post-Khmer Rouge Cambodia.[36] In 1991, the Security Council demonstrated its renewed vigor by condemning the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait on the same day of the attack, and later authorizing a US-led coalition that successfully repulsed the Iraqis.[37] Undersecretary-General Brian Urquhart later described the hopes raised by these successes as a "false renaissance" for the organization, given the more troubled missions that followed.[38]

Though the UN Charter had been written primarily to prevent aggression by one nation against another, in the early 1990s, the UN faced a number of simultaneous, serious crises within nations such as Haiti, Mozambique and the former Yugoslavia.[39] The UN mission to Bosnia faced "worldwide ridicule" for its indecisive and confused mission in the face of ethnic cleansing.[40] In 1994, the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda failed to intervene in the Rwandan Genocide in the face of Security Council indecision.[41]

In the late 1990s, UN-authorised international interventions took a wider variety of forms. The UN mission in the 1991–2002 Sierra Leone Civil War was supplemented by British Royal Marines, and the UN-authorised 2001 invasion of Afghanistan was overseen by NATO.[42] In 2003, the US invaded Iraq despite failing to pass a UN Security Council resolution for authorization, prompting a new round of questioning of the organization's effectiveness.[43] In the same decade, the Security Council intervened with peacekeepers in crises including the War in Darfur in Sudan and the Kivu conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In 2013, an internal review of UN actions in the final battles of the Sri Lankan Civil War in 2009 concluded that the organization had suffered "systemic failure".[44]

In November/December 2014, Egypt presented a motion proposing an expansion of the NPT (non-Proliferation Treaty), to include Israel and Iran; this proposal was due to increasing hostilities and destruction in the Middle-East connected to the Syrian Conflict as well as others. All members of the Security Council are signatory to the NPT.[45]

Role

UN Security Council Resolutions | ||

|---|---|---|

Sources: UN Security Council · UNBISnet · Wikisource | ||

1 to 100 (1946–1953) | ||

101 to 200 (1953–1965) | ||

201 to 300 (1965–1971) | ||

301 to 400 (1971–1976) | ||

401 to 500 (1976–1982) | ||

501 to 600 (1982–1987) | ||

601 to 700 (1987–1991) | ||

701 to 800 (1991–1993) | ||

801 to 900 (1993–1994) | ||

901 to 1000 (1994–1995) | ||

1001 to 1100 (1995–1997) | ||

1101 to 1200 (1997–1998) | ||

1201 to 1300 (1998–2000) | ||

1301 to 1400 (2000–2002) | ||

1401 to 1500 (2002–2003) | ||

1501 to 1600 (2003–2005) | ||

1601 to 1700 (2005–2006) | ||

1701 to 1800 (2006–2008) | ||

1801 to 1900 (2008–2009) | ||

1901 to 2000 (2009–2011) | ||

2001 to 2100 (2011–2013) | ||

2101 to 2200 (2013–2015) | ||

2201 to 2300 (2015–2016) | ||

2301 to 2400 (2016–2018) | ||

2401 to 2500 (2018–present) | ||

|

The UN's role in international collective security is defined by the UN Charter, which authorizes the Security Council to investigate any situation threatening international peace; recommend procedures for peaceful resolution of a dispute; call upon other member nations to completely or partially interrupt economic relations as well as sea, air, postal, and radio communications, or to sever diplomatic relations; and enforce its decisions militarily, or by any means necessary. The Security Council also recommends the new Secretary-General to the General Assembly and recommends new states for admission as member states of the United Nations.[46][47] The Security Council has traditionally interpreted its mandate as covering only military security, though US Ambassador Richard Holbrooke controversially persuaded the body to pass a resolution on HIV/AIDS in Africa in 2000.[48]

Under Chapter VI of the Charter, "Pacific Settlement of Disputes", the Security Council "may investigate any dispute, or any situation which might lead to international friction or give rise to a dispute". The Council may "recommend appropriate procedures or methods of adjustment" if it determines that the situation might endanger international peace and security.[49] These recommendations are generally considered to not be binding, as they lack an enforcement mechanism.[50] A minority of scholars, such as Stephen Zunes, have argued that resolutions made under Chapter VI are "still directives by the Security Council and differ only in that they do not have the same stringent enforcement options, such as the use of military force".[51]

Under Chapter VII, the Council has broader power to decide what measures are to be taken in situations involving "threats to the peace, breaches of the peace, or acts of aggression".[27] In such situations, the Council is not limited to recommendations but may take action, including the use of armed force "to maintain or restore international peace and security".[27] This was the legal basis for UN armed action in Korea in 1950 during the Korean War and the use of coalition forces in Iraq and Kuwait in 1991 and Libya in 2011.[52][53] Decisions taken under Chapter VII, such as economic sanctions, are binding on UN members; the Security Council is the only UN body with the authority to issue binding resolutions.[54][55]

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court recognizes that the Security Council has authority to refer cases to the Court in which the Court could not otherwise exercise jurisdiction.[56] The Council exercised this power for the first time in March 2005, when it referred to the Court "the situation prevailing in Darfur since 1 July 2002"; since Sudan is not a party to the Rome Statute, the Court could not otherwise have exercised jurisdiction.[57][58] The Security Council made its second such referral in February 2011 when it asked the ICC to investigate the Libyan government's violent response to the Libyan Civil War.[59]

Security Council Resolution 1674, adopted on 28 April 2006, "reaffirms the provisions of paragraphs 138 and 139 of the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document regarding the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity".[60] The Security Council reaffirmed this responsibility to protect in Resolution 1706 on 31 August of that year.[61] These resolutions commit the Security Council to take action to protect civilians in an armed conflict, including taking action against genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity.[62]

Members

Permanent members

The Security Council's five permanent members, below, have the power to veto any substantive resolution; this allows a permanent member to block adoption of a resolution, but not to prevent or end debate.[63]

| Country | Regional group | Current state representation | Former state representation |

|---|---|---|---|

China | Asia-Pacific | ||

France | Western Europe and Others | ||

Russia | Eastern Europe | ||

United Kingdom | Western Europe and Others | — | |

United States | Western Europe and Others | — |

At the UN's founding in 1945, the five permanent members of the Security Council were the Republic of China, the French Republic, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. There have been two major seat changes since then. China's seat was originally held by Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist Government, the Republic of China. However, the Nationalists were forced to retreat to the island of Taiwan in 1949, during the Chinese Civil War. The Communist government assumed control of mainland China, thenceforth known as the People's Republic of China. In 1971, General Assembly Resolution 2758 recognized the People's Republic as the rightful representative of China in the UN and gave it the seat on the Security Council that had been held by the Republic of China, which was expelled from the UN altogether with no opportunity of membership as a separate nation.[32] After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Russian Federation was recognized as the legal successor state of the Soviet Union and maintained the latter's position on the Security Council.[64] Additionally, France reformed its government into the French Fifth Republic in 1958, under the leadership of Charles de Gaulle. France maintained its seat as there was no change in its international status or recognition, although many of its overseas possessions eventually became independent.[65]

The five permanent members of the Security Council were the victorious powers in World War II[66] and have maintained the world's most powerful military forces ever since. They annually topped the list of countries with the highest military expenditures.[67] In 2013, they spent over US$1 trillion combined on defence, accounting for over 55% of global military expenditures (the US alone accounting for over 35%).[67] They are also among the world's largest arms exporters[68] and are the only nations officially recognized as "nuclear-weapon states" under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), though there are other states known or believed to be in possession of nuclear weapons.[69]

Veto power

Number of resolutions vetoed by each of the five permanent members of the Security Council between 1946 and 2017[70]

Current permanent and other members of UNSC

Under Article 27 of the UN Charter, Security Council decisions on all substantive matters require the affirmative votes of nine members. A negative vote or "veto" by a permanent member prevents adoption of a proposal, even if it has received the required votes.[63] Abstention is not regarded as a veto in most cases, though all five permanent members must actively concur to amend the UN Charter or to recommend the admission of a new UN member state.[54] Procedural matters are not subject to a veto, so the veto cannot be used to avoid discussion of an issue. The same holds for certain decisions that directly regard permanent members.[63] A majority of vetoes are used not in critical international security situations, but for purposes such as blocking a candidate for Secretary-General or the admission of a member state.[71]

In the negotiations building up to the creation of the UN, the veto power was resented by many small countries, and in fact was forced on them by the veto nations – US, UK, China, France and the Soviet Union – through a threat that without the veto there will be no UN. Here is a description by Francis O. Wilcox, an adviser to US delegation to the 1945 conference: "At San Francisco, the issue was made crystal clear by the leaders of the Big Five: it was either the Charter with the veto or no Charter at all. Senator Connally [from the US delegation] dramatically tore up a copy of the Charter during one of his speeches and reminded the small states that they would be guilty of that same act if they opposed the unanimity principle. 'You may, if you wish,' he said, 'go home from this Conference and say that you have defeated the veto. But what will be your answer when you are asked: "Where is the Charter"?'"[72]

As of 2012, 269 vetoes had been cast since the Security Council's inception.[a] In this period, China (ROC/PRC) used the veto 9 times, France 18, USSR/Russia 128, the UK 32, and the US 89. Roughly two-thirds of Soviet/Russian vetoes were in the first ten years of the Security Council's existence. Between 1996 and 2012, China vetoed 5 resolutions, Russia 7, and the US 13, while France and the UK did not use the veto.[71]

An early veto by Soviet Commissar Andrei Vishinsky blocked a resolution on the withdrawal of French forces from the then-colonies of Syria and Lebanon in February 1946; this veto established the precedent that permanent members could use the veto on matters outside of immediate concerns of war and peace. The USSR went on to veto matters including the admission of Austria, Cambodia, Ceylon, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Laos, Libya, Portugal, South Vietnam, and Transjordan as UN member states, delaying their joining by several years. Britain and France used the veto to avoid Security Council condemnation of their actions in the 1956 Suez Crisis. The first veto by the US came in 1970, blocking General Assembly action in Southern Rhodesia. From 1985 to 1990, the US vetoed 27 resolutions, primarily to block resolutions it perceived as anti-Israel but also to protect its interests in Panama and Korea. The USSR, US, and China have all vetoed candidates for Secretary-General, with the US using the veto to block the re-election of Boutros Boutros-Ghali in 1996.[73]

Non-permanent members

A chart representing the Security Council seats held by each of the regional groups. The United States, a WEOG observer, is treated as if it were a full member. This is not how the seats are arranged in actual meetings.

African Group

Asia-Pacific Group

Eastern European Group

Group of Latin American and Caribbean States (GRULAC)

Western European and Others Group (WEOG)

Along with the five permanent members, the Security Council of the United Nations has temporary members that hold their seats on a rotating basis by geographic region. Non-permanent members may be involved in global security briefings.[74] In its first two decades, the Security Council had six non-permanent members, the first of which were Australia, Brazil, Egypt, Mexico, the Netherlands, and Poland. In 1965, the number of non-permanent members was expanded to ten.[75]

These ten non-permanent members are elected by the United Nations General Assembly for two-year terms starting on 1 January, with five replaced each year.[76] To be approved, a candidate must receive at least two-thirds of all votes cast for that seat, which can result in deadlock if there are two roughly evenly matched candidates. In 1979, a standoff between Cuba and Colombia only ended after three months and a record 154 rounds of voting; both eventually withdrew in favour of Mexico as a compromise candidate.[77] A retiring member is not eligible for immediate re-election.[78]

The African Group is represented by three members; the Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia-Pacific, and Western European and Others groups by two apiece; and the Eastern European Group by one. Traditionally, one of the seats assigned to either the Asia-Pacific Group or the African Group is filled by a nation from the Arab world.[79] Currently, elections for terms beginning in even-numbered years select two African members, and one each within Eastern Europe, Asia-Pacific, and Latin America and the Caribbean. Terms beginning in odd-numbered years consist of two Western European and Other members, and one each from Asia-Pacific, Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean.[77]

During the 2016 United Nations Security Council election, neither Italy nor the Netherlands met the required two-thirds majority for election. They subsequently agreed to split the term of the Western European and Others Group. It was the first time in over five decades that two members agreed to do so;[80] Usually, intractable deadlocks are resolved by the candidate countries withdrawing in favour of a third member state.

The current elected members, with the regions they were elected to represent, are as follows:[76][81]

| Term | Africa | Asia-Pacific | Eastern Europe | Latin America and Caribbean | Western Europe and Other | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | ||||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||||

| 2020 | ||||||||||

President

United Nations Security Council by political international per country's head of government. Blue: International Democrat Union; red: Progressive Alliance; yellow: Liberal International; dark red: International Communist Seminar; gray: none or independent.

The role of president of the Security Council involves setting the agenda, presiding at its meetings and overseeing any crisis. The president is authorized to issue both Presidential Statements (subject to consensus among Council members) and notes,[82][83] which are used to make declarations of intent that the full Security Council can then pursue.[83] The presidency of the Council is held by each of the members in turn for one month, following the English alphabetical order of the Member States names.[84]

The list of nations that will hold the Presidency in 2019 is as follows:[85]

| Country | Month |

|---|---|

| January | |

| February | |

| March | |

| April | |

| May | |

| June | |

| July | |

| August | |

| September | |

| October | |

| November | |

| December |

Meeting locations

US President Barack Obama chairs a United Nations Security Council meeting

Unlike the General Assembly, the Security Council meets year-round. Each Security Council member must have a representative available at UN Headquarters at all times in case an emergency meeting becomes necessary.[86]

The Security Council generally meets in a designated chamber in the United Nations Conference Building in New York City. The chamber was designed by the Norwegian architect Arnstein Arneberg and was a gift from Norway. The mural painted by the Norwegian artist Per Krohg depicts a phoenix rising from its ashes, symbolic of the world's rebirth after World War II.[87]

The Security Council has also held meetings in cities including Nairobi, Kenya; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; Panama City, Panama; and Geneva, Switzerland.[86] In March 2010, the Security Council moved into a temporary facility in the General Assembly Building as its chamber underwent renovations as part of the UN Capital Master Plan.[88] The renovations were funded by Norway, the chamber's original donor, for a total cost of US$5 million.[89] The chamber reopened on 16 April 2013.[90]

Consultation room

Because meetings in the Security Council Chamber are covered by the international press, proceedings are highly theatrical in nature. Delegates deliver speeches to justify their positions and attack their opponents, playing to the cameras and the audience at home. Delegations also stage walkouts to express their disagreement with actions of the Security Council.[91] Due to the public scrutiny of the Security Council Chamber,[92] all of the real work of the Security Council is conducted behind closed doors in "informal consultations".[93][94]

In 1978, West Germany funded the construction of a conference room next to the Security Council Chamber. The room was used for "informal consultations", which soon became the primary meeting format for the Security Council. In 1994, the French ambassador complained to the Secretary-General that "informal consultations have become the Council's characteristic working method, while public meetings, originally the norm, are increasingly rare and increasingly devoid of content: everyone knows that when the Council goes into public meeting everything has been decided in advance".[95] When Russia funded the renovation of the consultation room in 2013, the Russian ambassador called it "quite simply, the most fascinating place in the entire diplomatic universe".[96]

Only members of the Security Council are permitted in the conference room for consultations. The press is not admitted, and other members of the United Nations cannot be invited into the consultations.[97] No formal record is kept of the informal consultations.[98][99] As a result, the delegations can negotiate with each other in secret, striking deals and compromises without having their every word transcribed into the permanent record. The privacy of the conference room also makes it possible for the delegates to deal with each other in a friendly manner. In one early consultation, a new delegate from a Communist nation began a propaganda attack on the United States, only to be told by the Soviet delegate, "We don't talk that way in here."[94]

A permanent member can cast a "pocket veto" during the informal consultation by declaring its opposition to a measure. Since a veto would prevent the resolution from being passed, the sponsor will usually refrain from putting the resolution to a vote. Resolutions are only vetoed if the sponsor feels so strongly about a measure that it wishes to force the permanent member to cast a formal veto.[93][100] By the time a resolution reaches the Security Council Chamber, it has already been discussed, debated, and amended in the consultations. The open meeting of the Security Council is merely a public ratification of a decision that has already been reached in private.[101][93] For example, Resolution 1373 was adopted without public debate in a meeting that lasted just five minutes.[93][102]

The Security Council holds far more consultations than public meetings. In 2012, the Security Council held 160 consultations, 16 private meetings, and 9 public meetings. In times of crisis, the Security Council still meets primarily in consultations, but it also holds more public meetings. After the outbreak of the Ukraine crisis in 2013, the Security Council returned to the patterns of the Cold War, as Russia and the Western countries engaged in verbal duels in front of the television cameras. In 2016, the Security Council held 150 consultations, 19 private meetings, and 68 public meetings.[103]

Subsidiary organs/bodies

Article 29 of the Charter provides that the Security Council can establish subsidiary bodies in order to perform its functions. This authority is also reflected in Rule 28 of the Provisional Rules of Procedure. The subsidiary bodies established by the Security Council are extremely heterogenous. On the one hand, they include bodies such as the Security Council Committee on Admission of New Members. On the other hand, both the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda were also created as subsidiary bodies of the Security Council. The by now numerous Sanctions Committees (see Category:United Nations Security Council sanctions regimes) established in order to oversee implementation of the various sanctions regimes are also subsidiary bodies of the Council.

United Nations peacekeepers

After approval by the Security Council, the UN may send peacekeepers to regions where armed conflict has recently ceased or paused to enforce the terms of peace agreements and to discourage combatants from resuming hostilities. Since the UN does not maintain its own military, peacekeeping forces are voluntarily provided by member states. These soldiers are sometimes nicknamed "Blue Helmets" for their distinctive gear.[104][105] The peacekeeping force as a whole received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1988.[106]

Bolivian "Blue Helmet" at an exercise in Chile

In September 2013, the UN had 116,837 peacekeeping soldiers and other personnel deployed on 15 missions. The largest was the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), which included 20,688 uniformed personnel. The smallest, United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP), included 42 uniformed personnel responsible for monitoring the ceasefire in Jammu and Kashmir. Peacekeepers with the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO) have been stationed in the Middle East since 1948, the longest-running active peacekeeping mission.[107]

UN peacekeepers have also drawn criticism in several postings. Peacekeepers have been accused of child rape, soliciting prostitutes, or sexual abuse during various peacekeeping missions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[108] Haiti,[109] Liberia,[110] Sudan and what is now South Sudan,[111] Burundi and Ivory Coast.[112] Scientists cited UN peacekeepers from Nepal as the likely source of the 2010–2013 Haiti cholera outbreak, which killed more than 8,000 Haitians following the 2010 Haiti earthquake.[113]

The budget for peacekeeping is assessed separately from the main UN organisational budget; in the 2013–2014 fiscal year, peacekeeping expenditures totalled $7.54 billion.[107][114] UN peace operations are funded by assessments, using a formula derived from the regular funding scale, but including a weighted surcharge for the five permanent Security Council members. This surcharge serves to offset discounted peacekeeping assessment rates for less developed countries. In 2013, the top 10 providers of assessed financial contributions to United Nations peacekeeping operations were the US (28.38%), Japan (10.83%), France (7.22%), Germany (7.14%), the United Kingdom (6.68%), China (6.64%), Italy (4.45%), Russian Federation (3.15%), Canada (2.98%), and Spain (2.97%).[115]

Criticism and evaluations

In examining the first sixty years of the Security Council's existence, British historian Paul Kennedy concludes that "glaring failures had not only accompanied the UN's many achievements, they overshadowed them", identifying the lack of will to prevent ethnic massacres in Bosnia and Rwanda as particular failures.[116] Kennedy attributes the failures to the UN's lack of reliable military resources, writing that "above all, one can conclude that the practice of announcing (through a Security Council resolution) a new peacekeeping mission without ensuring that sufficient armed forces will be available has usually proven to be a recipe for humiliation and disaster".[117]

A 2005 RAND Corporation study found the UN to be successful in two out of three peacekeeping efforts. It compared UN nation-building efforts to those of the United States, and found that seven out of eight UN cases are at peace.[118] Also in 2005, the Human Security Report documented a decline in the number of wars, genocides and human rights abuses since the end of the Cold War, and presented evidence, albeit circumstantial, that international activism—mostly spearheaded by the UN—has been the main cause of the decline in armed conflict since the end of the Cold War.[119]

Scholar Sudhir Chella Rajan argued in 2006 that the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, who are all nuclear powers, have created an exclusive nuclear club that predominately addresses the strategic interests and political motives of the permanent members—for example, protecting the oil-rich Kuwaitis in 1991 but poorly protecting resource-poor Rwandans in 1994.[120] Since three of the five permanent members are also European, and four are predominantly white Western nations, the Security Council has been described as a pillar of global apartheid by Titus Alexander, former Chair of Westminster United Nations Association.[121]

The Security Council's effectiveness and relevance is questioned by some because, in most high-profile cases, there are essentially no consequences for violating a Security Council resolution. During the Darfur crisis, Janjaweed militias, allowed by elements of the Sudanese government, committed violence against an indigenous population, killing thousands of civilians. In the Srebrenica massacre, Serbian troops committed genocide against Bosniaks, although Srebrenica had been declared a UN safe area, protected by 400 armed Dutch peacekeepers.[122]

The UN Charter gives all three powers of the legislative, executive, and judiciary branches to the Security Council.[123]

In his inaugural speech at the 16th Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement in August 2012, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei criticized the United Nations Security Council as having an "illogical, unjust and completely undemocratic structure and mechanism" and called for a complete reform of the body.[124]

The Security Council has been criticized for failure in resolving many conflicts, including Cyprus, Sri Lanka, Syria, Kosovo and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, reflecting the wider short-comings of the UN.

For example; At the 68th Session of the UN General Assembly, New Zealand Prime Minister John Key heavily criticized the UN's inaction on Syria, more than two years after the Syrian civil war began.[125]

Membership reform

The G4 nations: Brazil, Germany, India, Japan.

Uniting for Consensus core members

Proposals to reform the Security Council began with the conference that wrote the UN Charter and have continued to the present day. As British historian Paul Kennedy writes, "Everyone agrees that the present structure is flawed. But consensus on how to fix it remains out of reach."[126]

There has been discussion of increasing the number of permanent members. The countries who have made the strongest demands for permanent seats are Brazil, Germany, India, and Japan. Japan and Germany, the main defeated powers in WWII, are now the UN's second- and third-largest funders respectively, while Brazil and India are two of the largest contributors of troops to UN-mandated peace-keeping missions.

Italy, the third main defeated power in WWII and now the UN's sixth-largest funder, leads a movement known as the Uniting for Consensus in opposition to the possible expansion of permanent seats. Core members of the group include Canada, South Korea, Spain, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, Turkey, Argentina and Colombia. Their proposal is to create a new category of seats, still non-permanent, but elected for an extended duration (semi-permanent seats). As far as traditional categories of seats are concerned, the UfC proposal does not imply any change, but only the introduction of small and medium size states among groups eligible for regular seats. This proposal includes even the question of veto, giving a range of options that goes from abolition to limitation of the application of the veto only to Chapter VII matters.

Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan asked a team of advisers to come up with recommendations for reforming the United Nations by the end of 2004. One proposed measure is to increase the number of permanent members by five, which, in most proposals, would include Brazil, Germany, India, and Japan (known as the G4 nations), one seat from Africa (most likely between Egypt, Nigeria or South Africa), and/or one seat from the Arab League.[127] On 21 September 2004, the G4 nations issued a joint statement mutually backing each other's claim to permanent status, together with two African countries. Currently the proposal has to be accepted by two-thirds of the General Assembly (128 votes).

The permanent members, each holding the right of veto, announced their positions on Security Council reform reluctantly. The United States has unequivocally supported the permanent membership of Japan and lent its support to India and a small number of additional non-permanent members. The United Kingdom and France essentially supported the G4 position, with the expansion of permanent and non-permanent members and the accession of Germany, Brazil, India and Japan to permanent member status, as well as an increase in the presence by African countries on the Council. China has supported the stronger representation of developing countries and firmly opposed Japan's membership.[128]

In 2017, it was reported that the G4 nations were willing to temporarily forgo veto power if granted permanent UNSC seats.[129] In September 2017, U.S. Representatives Ami Bera and Frank Pallone introduced a resolution (H.Res.535) in the US House of Representatives (115th United States Congress), seeking support for India for a permanent membership of the United Nations Security Council.[130]

See also

- Kazakhstan's membership in the United Nations Security Council

- Reform of the United Nations

United Nations Department of Political Affairs, provides secretarial support to the Security Council

United Nations Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee, a standing committee of the Security Council

Small Five Group, a group formed to improve the working methods of the Security Council

Notes

^ This figure and the figures that follow exclude vetoes cast to block candidates for Secretary-General, as these occur in closed session; 43 such vetoes have occurred.[71]

References

Citations

^ "Article 7 (1) of Charter of the United Nations"..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Article 24 (1) of Charter of the United Nations".

^ "Article 4 (2) of Charter of the United Nations".

^ "Article 108 of Charter of the United Nations".

^ "Article 23 (1) of the Charter of the United Nations". www.un.org. United Nations. 26 June 1945. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

^ "Peacekeeping Fact Sheet". United Nations. 30 April 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

^ Kennedy 2006, p. 5.

^ Kennedy 2006, p. 8.

^ Kennedy 2006, p. 10.

^ Kennedy 2006, p. 13–24.

^ Hoopes & Brinkley 2000, pp. 1–55.

^ "Declaration by United Nations". United Nations. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

^ Osmańczyk 2004, p. 2445.

^ Urquhart, Brian. Looking for the Sheriff. New York Review of Books, 16 July 1998.|access-date=requires|url=(help)

^ Gaddis 2000.

^ Video: Allies Study Post-War Security Etc. (1944). Universal Newsreel. 1944. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

^ Meisler 1995, p. 9.

^ Meisler 1995, pp. 10–13.

^ abcd "Milestones in United Nations History". Department of Public Information, United Nations. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

^ Schlesinger 2003, p. 196.

^ Meisler 1995, pp. 18–19.

^ "What is the Security Council?". United Nations. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

^ Meisler 1995, p. 35.

^ Meisler 1995, pp. 58–59.

^ Meisler 1995, p. 114.

^ Kennedy 2006, pp. 38, 55–56.

^ abc "Charter of the United Nations: Chapter VII: Action with Respect to Threats to the Peace, Breaches of the Peace, and Acts of Aggression". United Nations. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

^ Meisler 1995, pp. 115–134.

^ Kennedy 2006, pp. 61–62.

^ Meisler 1995, pp. 156–157.

^ Kennedy 2006, p. 59.

^ ab Meisler 1995, pp. 195–197.

^ Meisler 1995, pp. 167–168, 224–225.

^ Meisler 1995, p. 286.

^ Fasulo 2004, p. 43; Meisler 1995, p. 334.

^ Meisler 1995, pp. 252–256.

^ Meisler 1995, pp. 264–277.

^ Meisler 1995, p. 334.

^ Kennedy 2006, pp. 66–67.

^ For quotation "worldwide ridicule", see Meisler 1995, p. 293; for description of UN missions in Bosnia, see Meisler 1995, pp. 312–329.

^ Kennedy 2006, p. 104.

^ Kennedy 2006, pp. 110–111.

^ Kennedy 2006, p. 111.

^ "UN failed during final days of Lankan ethnic war: Ban Ki-moon". FirstPost. Press Trust of India. 25 September 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

^ "UNODA – Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT)". United Nations.

^ "Charter of the United Nations: Chapter II: Membership". United Nations. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

^ "Charter of the United Nations: Chapter V: The Security Council". United Nations. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

^ Fasulo 2004, p. 46.

^ "Charter of the United Nations: Chapter VI: Pacific Settlement of Disputes". United Nations. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

^ See Fomerand 2009, p. 287; Hillier 1998, p. 568; Köchler 2001, p. 21; Matthews 1993, p. 130; Neuhold 2001, p. 66. For lack of enforcement mechanism, see Magliveras 1999, p. 113.

^ Zunes 2004, p. 291.

^ Kennedy 2006, pp. 56–57.

^ "Security Council Approves 'No-Fly Zone' Over Libya, Authorizing 'All Necessary Measures' to Protect Civilians, by Vote of 10 in Favour with 5 Abasentions". United Nations. 17 March 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

^ ab Fomerand 2009, p. 287.

^ Fasulo 2004, p. 39.

^ Article 13 of the Rome Statute. United Nations. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

^ "Security Council Refers Situation in Darfur, Sudan, To Prosecutor of International Criminal Court" (Press release). United Nations Security Council. 31 March 2006. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

^ Wadhams, Nick (2 April 2005). "Bush relents to allow UN vote on Sudan war crimes". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

^ Gray-Block, Aaron and Greg Roumeliotis (27 February 2011). "Q+A: How will the world's war crimes court act on Libya?". Reuters. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

^ "Resolution 1674 (2006)". UN Security Council via Refworld. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

^ Mikulaschek 2010, p. 20.

^ Mikulaschek 2010, p. 49.

^ abc Fasulo 2004, pp. 40–41.

^ Blum 1992.

^ Permanent members of the United Nations Security Council

^ Kennedy 2006, p. 70.

^ ab "SIPRI Military Expenditure Database". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

^ Nichols, Michelle (27 July 2012). "United Nations fails to agree landmark arms-trade treaty". Reuters. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

^ Medalia, Jonathan (14 November 1996). "92099: Nuclear Weapons Testing and Negotiation of a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty". Global Security. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

^ Global Policy Forum (2008): "Changing Patterns in the Use of the Veto in the Security Council". Retrieved 25 August 2008.

^ abc "Changing Patterns in the Use of the Veto in The Security Council" (PDF). Global Policy Forum. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

^ Wilcox 1945.

^ Kennedy 2006, pp. 52–54.

^ U.N. Security Council Briefing on the U.S. Air Strike in Syria on YouTube Time

^ "The UN Security Council". United Nations Foundation. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

^ ab "Current Members". United Nations. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

^ ab "Special Research Report No. 4Security Council Elections 201121 September 2011". Security Council Report. Archived from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

^ "Charter of the United Nations: Chapter V: The Security Council". United Nations. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

^ Malone, David (25 October 2003). "Reforming the Security Council: Where Are the Arabs?". The Daily Star. Beirut. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

^ "General Assembly Elects 4 New Non-permanent Members to Security Council, as Western and Others Group Fails to Fill Final Vacancy". United Nations. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

^ "General Assembly Elects Belgium, Dominican Republic, Germany, Indonesia, South Africa as Non-permanent Members of Security Council". United Nations. 8 June 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

^ "Notes by the president of the Security Council". United Nations. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

^ ab "UN Security Council: Presidential Statements 2008". United Nations. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

^ "Security Council Presidency in 2011 – United Nations Security Council". United Nations. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

^ "Security Council Presidency in 2019". United Nations Security Council. United Nations. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

^ ab "What is the Security Council?". United Nations. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

^ "The Security Council". United Nations Cyberschoolbus. United Nations. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

^ "UN Capital Master Plan Timeline". United Nations. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

^ "An unrecognizable Security Council Chamber". Norway Mission to the UN. 28 August 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

^ "Secretary-General, at inauguaration of renovated Security Council Chamber, says room speaks 'language of dignity and seriousness'". United Nations. 16 April 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

^ Haidar, Suhasini (1 September 2015). "India's walkout from UNSC was a turning point: Natwar". The Hindu.According to Mr. Singh, posted at India's permanent mission at the U.N. then, 1965 was a "turning point" for the U.N. on Kashmir, and a well-planned "walkout" from the U.N. Security Council by the Indian delegation as a protest against Pakistani Foreign Minister (and later PM) Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's speech ensured Kashmir was dropped from the UNSC agenda for all practical purposes.

^ Hovell, Devika (2016). The Power of Process: The Value of Due Process in Security Council Sanctions Decision-making. Oxford University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780198717676.

^ abcd De Wet, Erika; Nollkaemper, André; Dijkstra, Petra, eds. (2003). Review of the Security Council by member states. Antwerp: Intersentia. pp. 31–32. ISBN 9789050953078.

^ ab Bosco, David L. (2009). Five to Rule Them All: the UN Security Council and the Making of the Modern World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 9780195328769.

^ Elgebeily, Sherif (2017). The Rule of Law in the United Nations Security Council Decision-Making Process: Turning the Focus Inwards. pp. 54–55. ISBN 9781315413440.

^ Sievers, Loraine; Daws, Sam (2014). The Procedure of the UN Security Council (4 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191508431.

^ "Security Council Handbook Glossary". United Nations Security Council."Consultations of the whole" are consultations held in private with all 15 Council members present. Such consultations are held in the Consultations Room, are announced in the UN Journal, have an agreed agenda and interpretation, and may involve one or more briefers. The consultations are closed to non-Council Member States. "Informal consultations" mostly refer to "consultations of the whole", but in different contexts may also refer to consultations among the 15 Council members or only some of them held without a Journal announcement and interpretation.

^ "United Nations Security Council Meeting records". Retrieved 10 February 2017.The preparatory work for formal meetings is conducted in informal consultations for which no public record exists.

^ "Frequently Asked Questions". United Nations Security Council.Both open and closed meetings are formal meetings of the Security Council. Closed meetings are not open to the public and no verbatim record of statements is kept, instead the Security Council issues a Communiqué in line with Rule 55 of its Provisional Rules of Procedure. Consultations are informal meetings of the Security Council members and are not covered in the Repertoire.

^ "The Veto" (PDF). Security Council Report. 2015 (3). 19 October 2015.

^ Reid, Natalie (January 1999). "Informal Consultations". Global Policy Forum.

^ "Meeting record, Security Council, 4385th meeting". United Nations Repository. United Nations. 28 September 2001. S/PV.4385.

^ "Highlights of Security Council Practice 2016". Unite. United Nations. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

^ Fasulo 2004, p. 52.

^ Coulon 1998, p. ix.

^ Nobel Prize. "The Nobel Peace Prize 1988". Retrieved 3 April 2011.

^ ab "United Nations Peacekeeping Operations". United Nations. 30 September 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

^ Lynch, Colum (16 December 2004). "U.N. Sexual Abuse Alleged in Congo". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

^ "UN troops face child abuse claims". BBC News. 30 November 2006. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

^ "Aid workers in Liberia accused of sex abuse". The New York Times. 8 May 2006. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

^ Holt, Kate (4 January 2007). "UN staff accused of raping children in Sudan". The Telegraph. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

^ "Peacekeepers 'abusing children'". BBC. 28 May 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

^ Watson, Ivan and Joe Vaccarello (10 October 2013). "U.N. sued for 'bringing cholera to Haiti', causing outbreak that killed thousands". CNN. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

^ Fasulo 2004, p. 115.

^ "Financing of UN Peacekeeping Operations". United Nations. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

^ Kennedy 2006, pp. 101–103, 110.

^ Kennedy 2006, p. 110.

^ RAND Corporation. "The UN's Role in Nation Building: From the Congo to Iraq" (PDF). Retrieved 30 December 2008.

^ Human Security Centre. "The Human Security Report 2005". Archived from the original on 28 July 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

^ Rajan, Sudhir Chella (2006). "Global Politics and Institutions" (PDF). GTI Paper Series: Frontiers of a Great Transition. Tellus Institute. 3. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

^ Alexander 1996, pp. 158–160.

^ Deni 2007, p. 71: "As Serbian forces attacked Srebrenica in July 1995, the [400] Dutch soldiers escorted women and children out of the city, leaving behind roughly 7,500 Muslim men who were subsequently massacred by the attacking Serbs."

^ Creery, Janet (2004). "Read the fine print first". Peace Magazine (Jan–Feb 1994): 20. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

^ "Supreme Leader’s Inaugural Speech at 16th NAM Summit". Non-Aligned Movement News Agency. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

^ Key compromises on UN Syria deal Archived 30 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. 3 News NZ. 28 September 2013.

^ Kennedy 2006, p. 76.

^ "UN Security Council Reform May Shadow Annan's Legacy". Voice of America. 1 November 2006. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

^ "US embassy cables: China reiterates 'red lines'". The Guardian. 29 November 2010. Retrieved 11 December 2011.[I]t would be difficult for the Chinese public to accept Japan as a permanent member of the UNSC.

^ "India Offers To Temporarily Forgo Veto Power If Granted Permanent UNSC Seat". HuffPost. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

^ "US congressmen move resolution in support of India's UN security council claim". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

Sources

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Alexander, Titus (1996). Unravelling Global Apartheid: An Overview of World Politics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-7456-1353-6.

Blum, Yehuda Z. (1992). "Russia Takes Over the Soviet Union's Seat at the United Nations" (PDF). European Journal of International Law. 3 (2): 354–362. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

Coulon, Jocelyn (1998). Soldiers of Diplomacy: The United Nations, Peacekeeping, and the New World Order. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-0899-2.

Deni, John R. (2007). Alliance Management and Maintenance: Restructuring NATO for the 21st Century. Aldershot, England: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-7039-1.

Fasulo, Linda (2004). An Insider's Guide to the UN. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10155-3.

Fomerand, Jacques (2009). The A to Z of the United Nations. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5547-2.

Gaddis, John Lewis (2000) [1972]. The United States and the Origins of the Cold War, 1941–1947. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12239-9.

Hillier, Timothy (1998). Sourcebook on Public International Law. Sourcebook Series. London: Cavendish Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85941-050-9.

Hoopes, Townsend; Brinkley, Douglas (2000) [1997]. FDR and the Creation of the U.N. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08553-2.

Kennedy, Paul (2006). The Parliament of Man: The Past, Present, and Future of the United Nations. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-50165-4.

Köchler, Hans (2001). The Concept of Humanitarian Intervention in the Context of Modern Power: Is the Revival of the Doctrine of "Just War" Compatible with the International Rule of Law?. Studies in International Relations. 26. Vienna: International Progress Organization. ISBN 978-3-90070420-9.

Magliveras, Konstantinos D. (1999). Exclusion from Participation in International Organisations: The Law and Practice behind Member States' Expulsion and Suspension of Membership. Studies and Materials on the Settlement of International Disputes. 5. The Hague: Kluwer Law International. ISBN 978-904111239-2.

Manchester, William; Reid, Paul (2012). The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill. Volume 3: Defender of the Realm. New York: Little Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-54770-3.

Matthews, Ken (1993). The Gulf Conflict and International Relations. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-07519-0.

Meisler, Stanley (1995). United Nations: The First Fifty Years. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.

Mikulaschek, Christoph (2010). "Report from the 39th International Peace Institute Vienna Seminar on Peacemaking and Peacekeeping". In Winkler, Hans; Rød-Larsen, Terje; Mikulaschek, Christoph. The UN Security Council and the Responsibility to Protect: Policy, Process, and Practice (PDF). Favorita Papers. Diplomatic Academy of Vienna. pp. 20–49. ISBN 978-3-902021-67-0. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

Mires, Charlene (2013). Capital of the World: The Race to Host the United Nations. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-0794-4.

Neuhold, Hanspeter (2001). "The United Nations System for the Peaceful Settlement of International Disputes". In Cede, Frank; Sucharipa-Behrmann, Lilly. The United Nations: Law and Practice. The Hague: Kluwer Law International. ISBN 978-904111563-8.

Osmańczyk, Edmund Jan (2004). Mango, Anthony, ed. Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements. 4. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-93924-9.

Schlesinger, Stephen C. (2003). Act of Creation: The Founding of the United Nations: A Story of Super Powers, Secret Agents, Wartime Allies and Enemies, and Their Quest for a Peaceful World. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-3324-3.

Wilcox, Francis O. (1945). "The Yalta Voting Formula". American Political Science Review. 39 (5): 943–956. doi:10.2307/1950035. ISSN 0003-0554. JSTOR 1950035. (Subscription required (help)).

Zunes, Stephen (2004). "International Law, the UN and Middle Eastern Conflicts". Peace Review: A Journal of Social Justice. 16 (3): 285–292. doi:10.1080/1040265042000278513. ISSN 1040-2659. (Subscription required (help)).

Further reading

Bailey, Sydney D.; Daws, Sam (1998). The Procedure of the UN Security Council (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-828073-6.

Bosco, David L. (2009). Five to Rule Them All: The UN Security Council and the Making of the Modern World. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532876-9.

Cockayne, James; Mikulaschek, Christoph; Perry, Chris (2010). The United Nations Security Council and Civil War: First Insights from a New Dataset. New York: International Peace Institute. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

Grieger, Gisela (2013). Reform of the UN Security Council (PDF). Library of the European Parliament. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

Hannay, David (2008). New World Disorder: The UN after the Cold War – An Insider's View. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-719-1.

Hurd, Ian (2007). After Anarchy: Legitimacy and Power in the United Nations Security Council. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12866-5.

Köchler, Hans (1991). The Voting Procedure in the United Nations Security Council: Examining a Normative Contradiction in the UN Charter and its Consequences on International Relations (PDF). Studies in International Relations. 17. Vienna: International Progress Organization. ISBN 978-3-90070410-0.

Lowe, Vaughan; Roberts, Adam; Welsh, Jennifer; Zaum, Dominik, eds. (2008). The United Nations Security Council and War: The Evolution of Thought and Practice since 1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953343-5.

Malone, David (1998). Decision-Making in the UN Security Council: The Case of Haiti, 1990–1997. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829483-2.

Matheson, Michael J. (2006). Council Unbound: The Growth of UN Decision Making on Conflict and Postconflict Issues after the Cold War. Washington: US Institute of Peace Press. ISBN 978-1-929223-78-7.

Roberts, Adam; Zaum, Dominik (2008). Selective Security: War and the United Nations Security Council since 1945. Adelphi Paper. 395. Abingdon, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-47472-6. ISSN 0567-932X.

Vreeland, James; Dreher, Axel (2014). The Political Economy of the United Nations Security Council: Money and Influence. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51841-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United Nations Security Council. |

- Official website

- UN Security Council Research Guide

- Global Policy Forum – UN Security Council

Security Council Report – information and analysis on the Council's activities

What's In Blue – a series of insights on evolving Security Council actions

- Center for UN Reform Education – information on current reform issues at the United Nations

- UN Democracy: hyperlinked transcripts of the United Nations General Assembly and the Security Council