Western Allied invasion of Germany

| Invasion of Germany | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of World War II | |||||||

American infantrymen of the U.S. 11th Armored Division supported by an M4 Sherman tank move through a smoke filled street in Wernberg, Germany, April 1945. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

4.5 million troops (91 Divisions)[2][3] ~17,000 tanks[4] 28,000 combat aircraft[5] ~63,000 artillery pieces[6] 970,000 motor vehicles[5] | Initial: ~1 million troops [7][8] ~500 operational tanks and assault guns[9] ~2,000 operational combat aircraft[10] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

United States 62,704 casualties including 15,009 killed[11] Canada 6,298 casualties including 1,482 killed[12] UK Unknown French Unknown | From January to May 1945: No reliable data available. Estimates range from 265,000 to 400,000 for all fronts.[13] Approx. 200,000 captured during Jan-March 1945 and 4.4 million surrendered in April–June 1945.[14] | ||||||

The Western Allied invasion of Germany was coordinated by the Western Allies during the final months of hostilities in the European theatre of World War II. In preparation for the Allied invasion of Germany, a series of Offensive Operations were designed to seize and capture the east and west bank of the Rhine River. Operation Veritable and Operation Grenade in February 1945, and Operation Lumberjack and Operation Undertone in March 1945. Allied invasion of Germany started with the Western Allies crossing the Rhine River on 22 March 1945 before fanning out and overrunning all of western Germany from the Baltic in the north to Austria in the south before the Germans surrendered on 8 May 1945. This is known as the "Central Europe Campaign" in United States military histories.

By early 1945, events favored the Allied forces in Europe. On the Western Front the Allies had been fighting in Germany with campaigns against the Siegfried Line since the Battle of Aachen and the Battle of Hurtgen Forest in late 1944 and by January 1945 had pushed the Germans back to their starting points during the Battle of the Bulge. The failure of this offensive exhausted Germany's strategic reserve, leaving it ill-prepared to resist the final Allied campaigns in Europe. Additional losses in the Rhineland further weakened the German Army, leaving shattered remnants of units to defend the east bank of the Rhine. On 7 March, the Allies seized the last remaining intact bridge across the Rhine at Remagen, and had established a large bridgehead on the river's east bank. During Operation Lumberjack, Operation Plunder and Operation Undertone in March 1945, German casualties during February–March 1945 are estimated at 400,000 men, including 280,000 men captured as prisoners of war.[15]

On the Eastern Front, the Soviet Red Army (including the Polish Armed Forces in the East under Soviet command) simultaneously with the Western Allies, had liberated most of Poland and began their offensive into Eastern Germany in February 1945, and by March were within striking distance of Berlin. The initial advance into Romania, the First Jassy-Kishinev Offensive in April and May 1944 was a failure; the second Offensive in August succeeded. The Red Army also pushed deep into Hungary (the Budapest Offensive) and eastern Czechoslovakia and temporarily halted at what is now the modern German border on the Oder-Neisse line. These rapid advances on the Eastern Front destroyed additional veteran German combat units and severely limited German Führer Adolf Hitler's ability to reinforce his Rhine defenses. As such, with the Western Allies making final preparations for their powerful offensive into the German heartland, victory was imminent.

Contents

1 Order of battle

1.1 Allied forces

1.2 German forces

2 Eisenhower's plans

3 Occupation process

4 Operations

4.1 U.S. 12th Army Group crosses the Rhine (22 March)

4.2 U.S. 6th Army Group crosses the Rhine (26 March)

4.3 British 21st Army Group plans Operation Plunder

4.4 Montgomery launches Operation Plunder (23 March)

4.5 German Army Group B surrounded in the Ruhr pocket (1 April)

4.6 Eisenhower switches his main thrust to U.S. 12th Army Group front (28 March)

4.7 Ruhr pocket cleared (18 April)

4.8 U.S. 12th Army Group prepares its final thrust

4.9 U.S. 12th Army Group advances to the Elbe (9 April)

4.10 U.S. First Army makes first contact with the advancing Soviets (25 April)

4.11 U.S. 6th Army Group heads for Austria

4.12 Link-up of U.S. forces in Germany and Italy (4 May)

4.13 British 21st Army Group crosses the Elbe (29 April)

4.14 German surrender (8 May)

5 Analysis

6 Footnotes

7 References

8 External links

Order of battle

Allied forces

At the very beginning of 1945, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force on the Western Front, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, had 73 divisions under his command in North-western Europe, of which 49 were infantry divisions, 20 armored divisions and four airborne divisions. Forty-nine of these divisions were American, 12 British, eight French, three Canadian and one Polish. Another seven American divisions arrived during February,[16] along with the British 5th Infantry Division and I Canadian Corps, both of which had arrived from the fighting on the Italian Front. As the invasion of Germany commenced, General Eisenhower had a total of 90 full-strength divisions under his command, with the number of armored divisions now reaching 25. The Allied front along the Rhine stretched 450 miles (720 km) from the river's mouth at the North Sea in the Netherlands to the Swiss border in the south.[17]

The Allied forces along this line were organized into three army groups. In the north, from the North Sea to a point about 10 miles (16 km) north of Cologne, was the 21st Army Group commanded by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. Within 21st Army Group the Canadian 1st Army (under Harry Crerar) held the left flank of the Allied line, with the British 2nd Army (Miles C. Dempsey) in the center and the U.S. 9th Army (William Hood Simpson) to the south. Holding the middle of the Allied line from the 9th Army's right flank to a point about 15 miles (24 km) south of Mainz was the 12th Army Group under the command of Lieutenant General Omar Bradley. Bradley had two American armies, the U.S. 1st Army (Courtney Hodges) on the left (north) and the U.S. 3rd Army (George S. Patton) on the right (south). Completing the Allied line to the Swiss border was the 6th Army Group commanded by Lieutenant General Jacob L. Devers, with the U.S. 7th Army (Alexander Patch) in the north and the French 1st Army (Jean de Lattre de Tassigny) on the Allied right, and southernmost, flank.[18]

As these three army groups cleared out the Wehrmacht west of the Rhine, Eisenhower began to rethink his plans for the final drive across the Rhine and into the heart of Germany. Originally, General Eisenhower had planned to draw all his forces up to the west bank of the Rhine, using the river as a natural barrier to help cover the inactive sections of his line. The main thrust beyond the river was to be made in the north by Montgomery's 21 Army Group, elements of which were to proceed east to a juncture with the U.S. 1st Army as it made a secondary advance northeast from below the Ruhr River. If successful, this pincer movement would envelop the industrial Ruhr area, neutralizing the largest concentration of German industrial capacity left.[19]

German forces

Facing the Allies was Oberbefehlshaber West ("Army Command West") commanded by Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, who had taken over from Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt on 10 March. Although Kesselring brought an outstanding track record as a defensive strategist with him from the Italian Campaign, he did not have the resources to make a coherent defense. During the fighting west of the Rhine up to March 1945, the German Army on the Western Front had been reduced to a strength of only 26 divisions, organized into three army groups (H, B and G). Little or no reinforcement was forthcoming as the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht continued to concentrate most forces against the Soviets; it was estimated that the Germans had 214 divisions on the Eastern Front in April.[20]

On 21 March, Army Group H headquarters became Oberbefehlshaber Nordwest ("Army Command Northwest") commanded by Ernst Busch leaving the former Army Group H commander—Johannes Blaskowitz—to lead "Army Command Netherlands" (25th Army) cut off in the Netherlands. Busch—whose main unit was the German 1st Parachute Army —was to form the right wing of the German defenses. In the center of the front, defending the Ruhr, Kesselring had Field Marshal Walther Model commanding Army Group B (15th Army and 5th Panzer Army) and in the south Paul Hausser's Army Group G (7th Army, 1st Army and 19th Army).[20][21]

Eisenhower's plans

After capturing the Ruhr, General Eisenhower planned to have the 21st Army Group continue its drive east across the plains of northern Germany to Berlin. The 12th and 6th Army Groups were to mount a subsidiary offensive to keep the Germans off balance and diminish their ability to stop the northern thrust. This secondary drive would also give Eisenhower a degree of flexibility in case the northern attack ran into difficulties.[19]

For several reasons, Eisenhower began to readjust these plans toward the end of March. First, his headquarters received reports that Soviet forces held a bridgehead over the Oder River, 30 miles (48 km) from Berlin. Since the Allied armies on the Rhine were more than 300 miles (480 km) from Berlin, with the Elbe River, 200 miles (320 km) ahead, still to be crossed it seemed clear that the Soviets would capture Berlin long before the Western Allies could reach it. Eisenhower thus turned his attention to other objectives, most notably a rapid meet-up with the Soviets to cut the German Army in two and prevent any possibility of a unified defense. Once this was accomplished the remaining German forces could be defeated in detail. [19]

In addition, there was the matter of the Ruhr. Although the Ruhr area still contained a significant number of Axis troops and enough industry to retain its importance as a major objective, Allied intelligence reported that much of the region's armament industry was moving southeast, deeper into Germany. This increased the importance of the southern offensives across the Rhine.[19]

Also focusing Eisenhower's attention on the southern drive was concern over the "National redoubt." According to rumor, Hitler's most fanatically loyal troops were preparing to make a lengthy, last-ditch stand in the natural fortresses formed by the rugged alpine mountains of southern Germany and western Austria. If they held out for a year or more, dissension between the Soviet Union and the Western Allies might give them political leverage for some kind of favorable peace settlement. In reality, by the time of the Allied Rhine crossings the Wehrmacht had suffered such severe defeats on both the Eastern and Western Fronts that it could barely manage to mount effective delaying actions, much less muster enough troops to establish a well-organized alpine resistance force. Still, Allied intelligence could not entirely discount the possibility that remnants of the German Army would attempt a suicidal last stand in the Alps. Denying this opportunity became another argument for rethinking the role of the southern drive through Germany.[22]

Perhaps the most compelling reason for increasing the emphasis on this southern drive had more to do with the actions of Americans than those of Germans. While Montgomery was carefully and cautiously planning for the main thrust in the north, complete with massive artillery preparation and an airborne assault, American forces in the south were displaying the kind of basic aggressiveness that Eisenhower wanted to see. On 7 March, Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges's U.S. 1st Army captured the last intact bridge over the Rhine at Remagen and steadily expanded the bridgehead.[22]

To the south in the Saar-Palatinate region, Lieutenant General George S. Patton's U.S. 3rd Army had dealt a devastating blow to the German 7th Army and, in conjunction with the U.S. 7th Army, had nearly destroyed the German 1st Army. In five days of battle, from 18–22 March, Patton's forces captured over 68,000 Germans. These bold actions eliminated the last German positions west of the Rhine. Although Montgomery's drive was still planned as the main effort, Eisenhower believed that the momentum of the American forces to the south should not be squandered by having them merely hold the line at the Rhine or make only limited diversionary attacks beyond it. By the end of March, the Supreme Commander thus leaned toward a decision to place more responsibility on his southern forces. The events of the first few days of the final campaign would be enough to convince him that this was the proper course of action.[22]

Occupation process

When Allied soldiers arrived in a town, its leaders and remaining residents typically used white flags, bedsheets, and tablecloths to signal surrender. The officer in charge of the unit capturing the area, typically a company or battalion, accepted responsibility over the town. Soldiers posted copies of General Eisenhower's Proclamation No. 1, which began with "We come as a victorious army, not as oppressors." The proclamation demanded compliance with all orders by the commanding officer, instituted a strict curfew and limited travel, and confiscated all communications equipment and weapons. After a day or two, specialized Office of Military Government, United States (OMGUS) units took over. Soldiers requisitioned housing and office space as needed from residents. At first this was done informally with occupants evicted immediately and taking with them few personal possessions, but the process became standardized, with three hours' notice and OMGUS personnel providing receipts for buildings' contents. The displaced residents nonetheless had to find housing on their own.[23]

Operations

On 19 March, Eisenhower told Bradley to prepare the 1st Army for a breakout from the Remagen bridgehead anytime after 22 March. The same day, in response to the 3rd Army's robust showing in the Saar-Palatinate region, and to have another strong force on the Rhine's east bank guarding the 1st Army's flank, Bradley gave Patton the go-ahead for an assault crossing of the Rhine as soon as possible.[24]

These were exactly the orders Patton had hoped for. The American general felt that if a sufficiently strong force could be thrown across the river and significant gains made, then Eisenhower might transfer responsibility for the main drive through Germany from Montgomery's 21st Army Group to Bradley's 12th. Patton also appreciated the opportunity he now had to beat Montgomery across the river and win for the 3rd Army the coveted distinction of making the first assault crossing of the Rhine in modern history. To accomplish this, he had to move quickly.[24]

On 21 March, Patton ordered his XII Corps to prepare for an assault over the Rhine on the following night, one day before Montgomery's scheduled crossing. While this was certainly short notice, it did not catch the XII Corps completely unaware. As soon as Patton had received the orders on the 19th to make a crossing, he had begun sending assault boats, bridging equipment, and other supplies forward from depots in Lorraine where they had been stockpiled since autumn in the expectation of just such an opportunity. Seeing this equipment moving up, his frontline soldiers did not need any orders from higher headquarters to tell them what it meant.[25]

The location of the river-crossing assault was critical. Patton knew that the most obvious place to jump the river was at Mainz or just downstream, north of the city. The choice was obvious because the Main River, flowing northward 30 miles (48 km) east of and parallel to the Rhine, turns west and empties into the Rhine at Mainz and an advance south of the city would involve crossing two rivers rather than one. However, Patton also realized that the Germans were aware of this difficulty and would expect his attack north of Mainz. Thus, he decided to feint at Mainz while making his real effort at Nierstein and Oppenheim, 9–10 mi (14–16 km) south of the city. Following this primary assault, which XII Corps would undertake, VIII Corps would execute supporting crossings at Boppard and St. Goar, 25–30 miles (40–48 km) northwest of Mainz.[25]

The terrain in the vicinity of Nierstein and Oppenheim was conducive to artillery support, with high ground on the west bank overlooking relatively flat land to the east. However, the same flat east bank meant that the bridgehead would have to be rapidly and powerfully reinforced and expanded beyond the river since there was no high ground for a bridgehead defense. The importance of quickly obtaining a deep bridgehead was increased by the fact that the first access to a decent road network was over 6 miles (9.7 km) inland at the town of Groß- Gerau.[25]

U.S. 12th Army Group crosses the Rhine (22 March)

The crossing of the Rhine between 22 and 28 March 1945.

On 22 March, with a bright moon lighting the late-night sky, elements of U.S. XII Corps′ 5th Infantry Division began the 3rd Army's Rhine crossing. At Nierstein assault troops did not meet any resistance. As the first boats reached the east bank, seven startled Germans surrendered and then paddled themselves unescorted to the west bank to be placed in custody. Upstream at Oppenheim, however, the effort did not proceed so casually. The first wave of boats was halfway across when the Germans began pouring machine-gun fire into their midst. An intense exchange of fire lasted for about thirty minutes as assault boats kept pushing across the river and those men who had already made it across mounted attacks against the scattered defensive strongpoints. Finally the Germans surrendered, and by midnight units moved out laterally to consolidate the crossing sites and to attack the first villages beyond the river. German resistance everywhere was sporadic, and the hastily mounted counterattacks invariably burned out quickly, causing few casualties. The Germans lacked both the manpower and the heavy equipment to make a more determined defense.[26]

By midafternoon on 23 March, all three regiments of the 5th Infantry Division were in the bridgehead, and an attached regiment from the 90th Infantry Division was crossing. Tanks and tank destroyers had been ferried across all morning, and by evening a Treadway bridge was open to traffic. By midnight, infantry units had pushed the boundary of the bridgehead more than 5 miles (8.0 km) inland, ensuring the unqualified success of the first modern assault crossing of the Rhine.[27]

Two more 3rd Army crossings—both by VIII Corps—quickly followed. In the early morning hours of 25 March, elements of the 87th Infantry Division crossed the Rhine to the north at Boppard, and then some 24 hours later elements of the 89th Infantry Division crossed 8 miles (13 km) south of Boppard at St. Goar. Although the defense of these sites was somewhat more determined than that XII Corps had faced, the difficulties of the Boppard and St. Goar crossings were compounded more by terrain than by German resistance. VIII Corps crossing sites were located along the Rhine Gorge, where the river had carved a deep chasm between two mountain ranges, creating precipitous canyon walls over 300 feet (91 m) high on both sides. In addition, the river flowed quickly and with unpredictable currents along this part of its course. Still, despite the terrain and German machine-gun and 20 millimetres (0.79 in) anti-aircraft cannon fire, VIII Corps troops managed to gain control of the east bank's heights, and by dark on 26 March, with German resistance crumbling all along the Rhine, they were preparing to continue the drive the next morning.[28]

U.S. 6th Army Group crosses the Rhine (26 March)

Adding to the Germans′ woes, the 6th Army Group made an assault across the Rhine on 26 March. At Worms, about 25 miles (40 km) south of Mainz, the 7th Army's XV Corps established a bridgehead, which it consolidated with the southern shoulder of the 3rd Army's bridgehead early the next day. After overcoming stiff initial resistance, XV Corps also advanced beyond the Rhine, opposed primarily by small German strongpoints sited in roadside villages.[28]

British 21st Army Group plans Operation Plunder

On the night of 23/24 March, after the XII Corps′ assault of the Rhine, Bradley had announced his success. The 12th Army Group commander said that American troops could cross the Rhine anywhere, without aerial bombardment or airborne troops, a direct jab at Montgomery whose troops were at that very moment preparing to launch their own Rhine assault following an intense and elaborate aerial and artillery preparation and with the assistance of two airborne divisions, the American 17th, and the British 6th.[28]

Field Marshal Montgomery was exhibiting his now legendary meticulous and circumspect approach to such enterprises, a lesson he had learned early in the North African Campaign against Rommel and one he could not easily forget. Thus, as his forces had approached the east bank of the river, Montgomery proceeded with one of the most intensive buildups of material and manpower of the war. His detailed plans, code-named Operation Plunder, were comparable to the Normandy invasion in terms of numbers of men and extent of equipment, supplies, and ammunition to be used. The 21st Army Group had 30 full-strength divisions, 11 each in the British 2nd and U.S. 9th Armies and eight in the Canadian 1st Army, providing Montgomery with more than 1,250,000 men.[28]

Plunder called for the 2nd Army to cross at three locations along the 21st Army Group front—at Rees, Xanten, and Rheinberg. The crossings would be preceded by several weeks of aerial bombing and a final massive artillery preparation. A heavy bombing campaign by USAAF and RAF forces, known as the "Interdiction of Northwest Germany", designed primarily to destroy the lines of communication and supply connecting the Ruhr to the rest of Germany had been underway since February.[29] The intention was to create a line from Bremen south to Neuwied. The main targets were rail yards, bridges, and communication centers, with a secondary focus on fuel processing and storage facilities and other important industrial sites. During the three days leading up to Montgomery's attack, targets in front of the 21st Army Group zone and in the Ruhr area to the southeast were pummeled by about 11,000 sorties, effectively sealing off the Ruhr while easing the burden on Montgomery's assault forces.[30]

Montgomery had originally planned to attach one corps of the U.S. 9th Army to the British 2nd Army, which would use only two of the corps′ divisions for the initial assault. The rest of the 9th Army would remain in reserve until the bridgehead was ready for exploitation. The 9th Army's commander—Lieutenant General William Hood Simpson—and the 2nd Army's Lieutenant-General Miles C. Dempsey took exception to this approach. Both believed that the plan squandered the great strength in men and equipment that the 9th Army had assembled and ignored the many logistical problems of placing the 9th Army's crossing sites within the 2nd Army's zone.[30]

Montgomery responded to these concerns by making a few small adjustments to the plan. Although he declined to increase the size of the American crossing force beyond two divisions, he agreed to keep it under 9th Army rather than 2nd Army control. To increase Simpson's ability to bring his army's strength to bear for exploitation, Montgomery also agreed to turn the bridges at Wesel, just north of the inter-army boundary, over to the 9th Army once the bridgehead had been secured.[30]

In the southernmost sector of the 21st Army Group's attack, the 9th Army's assault divisions were to cross the Rhine along an 11 miles (18 km) section of the front, south of Wesel and the Lippe River. This force would block any German counterattack from the Ruhr. Because of the poor road network on the east bank of this part of the Rhine, a second 9th Army corps was to cross over the promised Wesel bridges through the British zone north of the Lippe River, which had an abundance of good roads. After driving east nearly 100 miles (160 km), this corps was to meet elements of the 1st Army near Paderborn, completing the encirclement of the Ruhr.[30]

Another important aspect of Montgomery's plan was Operation Varsity, in which two divisions of Major General Matthew Ridgway's XVIII Airborne Corps were to make an airborne assault over the Rhine. In a departure from standard airborne doctrine, which called for a jump deep behind enemy lines several hours prior to an amphibious assault, Varsity′s drop zones were close behind the German front, within Allied artillery range. Additionally, to avoid being caught in the artillery preparation, the paratroopers would jump only after the amphibious troops had reached the Rhine's east bank. The wisdom of putting lightly-armed paratroopers so close to the main battlefield was debated, and the plan for amphibious forces to cross the Rhine prior to the parachute drop raised questions as to the utility of making an airborne assault at all. However, Montgomery believed that the paratroopers would quickly link up with the advancing river assault forces, placing the strongest force within the bridgehead as rapidly as possible. Once the bridgehead was secured the British 6th Airborne Division would be transferred to 2nd Army control, while the U.S. 17th Airborne Division would revert to 9th Army control.[31]

Montgomery launches Operation Plunder (23 March)

Plunder began on the evening of 23 March with the assault elements of the British 2nd Army massed against three main crossing sites: Rees in the north, Xanten in the center, and Wesel in the south. The two 9th Army divisions tasked for the assault concentrated in the Rheinberg area south of Wesel. At the northern crossing site, elements of British XXX Corps began the assault (Operation Turnscrew) about 21:00, attempting to distract the Germans from the main crossings at Xanten in the center and Rheinberg to the south. The initial assault waves crossed the river quickly, meeting only light opposition. Meanwhile, Operation Widgeon began 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Wesel as the 2nd Army's 1st Commando Brigade slipped across the river and waited within a mile of the city while it was demolished by one thousand tons of bombs delivered by RAF Bomber Command. Entering in the night, the commandos secured the city late on the morning of 24 March, although scattered resistance continued until dawn on the 25th. The 2nd Army's XII Corps and the 9th Army's XVI Corps began the main effort about 02:00 on 24 March, following a massive artillery and air bombardment.[31]

For the American crossing, the 9th Army commander—Lieutenant General Simpson—had chosen the veteran 30th and 79th Infantry Divisions of the XVI Corps. The 30th was to cross between Wesel and Rheinberg while the 79th assaulted south of Rheinberg. In reserve were the XVI Corps′ 8th Armored Division, and 35th and 75th Infantry Divisions, as well as the 9th Army's XIII and XIX Corps, each with three divisions. Simpson planned to commit the XIX Corps as soon as possible after the bridgehead had been secured, using the XIII Corps to hold the Rhine south of the crossing sites.[31]

After an hour of extremely intense artillery preparation, which General Eisenhower himself viewed from the front, the 30th Infantry Division began its assault. The artillery fire had been so effective and so perfectly timed that the assault battalions merely motored their storm boats across the river and claimed the east bank against almost no resistance. As subsequent waves of troops crossed, units fanned out to take the first villages beyond the river to only the weakest of opposition. An hour later, at 03:00, the 79th Infantry Division began its crossing upriver, achieving much the same results. As heavier equipment was ferried across the Rhine, both divisions began pushing east, penetrating 3–6 miles (4.8–9.7 km) into the German defensive line that day.[32]

Douglas C-47 transport aircraft drop hundreds of paratroopers on 24 March as part of Operation Varsity.

To the north, the British crossings had also gone well, with the ground and airborne troops linking up by nightfall. By then, the paratroopers had taken all their first day's objectives in addition to 3,500 prisoners.[32]

To the south, the discovery of a defensive gap in front of the 30th Infantry Division fostered the hope that a full-scale breakout would be possible on 25 March. When limited objective attacks provoked little response on the morning of the 25th, the division commander—Major General Leland S. Hobbs—formed two mobile task forces to make deeper thrusts with an eye toward punching through the defense altogether and breaking deep into the German rear. However, Hobbs had not fully taken into account the nearly nonexistent road network in front of the XVI Corps bridgehead. Faced with trying to make rapid advances through dense forest on rutted dirt roads and muddy trails, which could be strongly defended by a few determined soldiers and well placed roadblocks, the task forces advanced only about 2 miles (3.2 km) on the 25th. The next day they gained some more ground, and one even seized its objective, having slogged a total of 6 miles (9.7 km), but the limited progress forced Hobbs to abandon the hope for a quick breakout.[32]

In addition to the poor roads, the 30th Division's breakout attempts were also hampered by the German 116th Panzer Division. The only potent unit left for commitment against the Allied Rhine crossings in the north, the 116th began moving south from the Dutch-German border on 25 March against what the Germans considered their most dangerous threat, the U.S. 9th Army. The enemy armored unit began making its presence felt almost immediately, and by the end of 26 March the combination of the panzer division and the rough terrain had conspired to sharply limit the 30th Division's forward progress. With the 79th Infantry Division meeting fierce resistance to the south, General Simpson's only recourse was to commit some of his forces waiting on the west bank of the Rhine. Late on 26 March, the 8th Armored Division began moving into the bridgehead.[32]

Although the armored division bolstered his offensive capacity within the bridgehead, Simpson was more interested in sending the XIX Corps across the Wesel bridges, as Montgomery had agreed, and using the better roads north of the Lippe to outflank the enemy in front of the 30th Division. Unfortunately, because of pressure from the Germans in the northern part of the 2nd Army bridgehead, the British were having trouble completing their bridges at Xanten and were therefore bringing most of their traffic across the river at Wesel. With Montgomery allowing use of the Wesel bridges to the 9th Army for only five out of every 24 hours, and with the road network north of the Lippe under 2nd Army control, General Simpson was unable to commit or maneuver sufficient forces to make a rapid flanking drive.[33]

German Army Group B surrounded in the Ruhr pocket (1 April)

Encirclement of the Ruhr and other Allied operations between 29 March and 4 April 1945

By 28 March, the 8th Armored Division had expanded the bridgehead by only about 3 mi (4.8 km) and still had not reached Dorsten, a town about 15 mi (24 km) east of the Rhine, whose road junction promised to expand the XVI Corps′ offensive options. On the same day, however, Montgomery announced that the east bound roads out of Wesel would be turned over to the 9th Army on 30 March with the Rhine bridges leading into that city changing hands a day later. Also on 28 March, elements of the U.S. 17th Airborne Division—operating north of the Lippe River in conjunction with British armored forces—dashed to a point some 30 mi (48 km) east of Wesel, opening a corridor for the XIX Corps and handily outflanking Dorsten and the enemy to the south. General Simpson now had both the opportunity and the means to unleash the power of the 9th Army and begin in earnest the northern drive to surround the Ruhr.[33]

Simpson began by moving elements of the XIX Corps′ 2nd Armored Division into the XVI Corps bridgehead on 28 March with orders to cross the Lippe east of Wesel, thereby avoiding that city's traffic jams. After passing north of the Lippe on 29 March, the 2nd Armored Division broke out late that night from the forward position that the XVIII Airborne Corps had established around Haltern, 12 mi (19 km) northeast of Dorsten. On the 30th and 31st, the 2nd Armored made an uninterrupted 40 mi (64 km) drive east to Beckum, cutting two of the Ruhr's three remaining rail lines and severing the autobahn to Berlin. As the rest of the XIX Corps flowed into the wake of this spectacular drive, the 1st Army was completing its equally remarkable thrust around the southern and eastern edges of the Ruhr.[33]

The 1st Army's drive from the Remagen bridgehead began with a breakout before dawn on 25 March. German Field Marshal Walter Model—whose Army Group B was charged with the defense of the Ruhr—had deployed his troops heavily along the east-west Sieg River south of Cologne, thinking that the Americans would attack directly north from the Remagen bridgehead. Instead, the 1st Army struck eastward, heading for Giessen and the Lahn River, 65 mi (105 km) beyond Remagen, before turning north toward Paderborn and a linkup with the 9th Army. All three corps of the 1st Army participated in the breakout, which on the first day employed five infantry and two armored divisions. The U.S. VII Corps, on the left, had the hardest going due to the German concentration north of the bridgehead, yet its armored columns managed to advance 12 mi (19 km) beyond their line of departure. The U.S. III Corps, in the center, did not commit its armor on the first day of the breakout, but still made a gain of 4 mi (6.4 km). The U.S. V Corps on the right advanced 5–8 mi (8.0–12.9 km), incurring minimal casualties.[34]

Beginning the next day, 26 March, the armored divisions of all three corps turned these initial gains into a complete breakout, shattering all opposition and roaming at will throughout the enemy's rear areas. By the end of 28 March, General Hodges′ 1st Army had crossed the Lahn, having driven at least 50 mi (80 km) beyond the original line of departure and capturing thousands of German soldiers in the process. Nowhere, it seemed, were the Germans able to resist in strength. On 29 March, the 1st Army turned toward Paderborn, about 80 mi (130 km) north of Giessen, its right flank covered by the 3rd Army, which had broken out of its own bridgeheads and was headed northeast toward Kassel.[34]

A task force of the VII Corps′ 3rd Armored Division, which included some of the new M26 Pershing heavy tanks, spearheaded the drive for Paderborn on 29 March. By attaching an infantry regiment of the 104th Infantry Division to the armored division and following the drive closely with the rest of the 104th Division, the VII Corps was well prepared to hold any territory gained. Rolling northward 45 mi (72 km) without casualties, the mobile force stopped for the night 15 mi (24 km) from its objective. Taking up the advance again the next day, it immediately ran into stiff opposition from students of an SS panzer replacement training center located near Paderborn. Equipped with about 60 tanks, the students put up a fanatical resistance, stalling the American armor all day. When the task force failed to advance on 31 March, Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins—commander of the VII Corps—asked General Simpson if his 9th Army—driving eastward north of the Ruhr—could provide assistance. Simpson, in turn, ordered a combat command of the 2nd Armored Division—which had just reached Beckum—to make a 15 mi (24 km) advance southeast to Lippstadt, midway between Beckum and the stalled 3rd Armored Division spearhead. Early in the afternoon of 1 April elements of the 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions met at Lippstadt, linking the 9th and 1st Armies and sealing the prized Ruhr industrial complex—along with Model's Army Group B—within American lines.[34]

As March turned to April the offensive east of the Rhine was progressing in close accordance with Allied plans. All the armies assigned to cross the Rhine had elements east of the river, including the Canadian 1st Army in the north, which sent a division through the British bridgehead at Rees, and the French 1st Army in the south, which on 31 March established its own bridgehead by assault crossings at Germersheim and Speyer, about 50 mi (80 km) south of Mainz. With spectacular thrusts being made beyond the Rhine nearly every day and the enemy's capacity to resist fading at an ever-accelerating rate, the campaign to finish Germany was transitioning into a general pursuit.[35]

In the center of the Allied line, Eisenhower inserted a new army—the 15th Army, under U.S. 12th Army Group control—to hold the western edge of the Ruhr Pocket along the Rhine while the 9th and 1st Armies squeezed the remaining German defenders there from the north, east, and south. Following the reduction of the Ruhr, the 15th Army was to take over occupation duties in the region as the 9th,[36] 1st, and 3rd Armies pushed farther into Germany.[35]

Eisenhower switches his main thrust to U.S. 12th Army Group front (28 March)

On 28 March, as these developments unfolded, Eisenhower announced his decision to adjust his plans governing the future course of the offensive. Once the Ruhr was surrounded, he wanted the 9th Army transferred from the British 21st Army Group to the U.S. 12th Army Group. After the reduction of the Ruhr Pocket, the main thrust east would be made by Bradley's 12th Army Group in the center, rather than by Montgomery's 21st Army Group in the north as originally planned. Montgomery's forces were to secure Bradley's northern flank while Devers′ 6th U.S. Army Group covered Bradley's southern shoulder. Furthermore, the main objective was no longer Berlin, but Leipzig where a juncture with the Soviet Army would split the remaining German forces in two. Once this was done, the 21st Army Group would take Lübeck and Wismar on the Baltic Sea, cutting off the Germans remaining in the Jutland peninsula of Denmark, while the 6th U.S. Army Group and the 3rd Army drove south into Austria.[35]

The British Prime Minister and Chiefs of Staff strongly opposed the new plan. Despite the Russian proximity to Berlin, they argued that the city was still a critical political, if not military, objective. Eisenhower—supported by the American Chiefs of Staff—disagreed. His overriding objective was the swiftest military victory possible. Should the U.S. political leadership direct him to take Berlin, or if a situation arose in which it became militarily advisable to seize the German capital, Eisenhower would do so. Otherwise, he would pursue those objectives that would end the war soonest. In addition, since Berlin and the rest of Germany had already been divided into occupation zones by representatives of the Allied governments at the Yalta Conference, Eisenhower saw no political advantage in a race for Berlin. Any ground the western Allies gained in the future Soviet zone would merely be relinquished to the Soviets after the war. In the end the campaign proceeded as Eisenhower had planned it.[37]

Ruhr pocket cleared (18 April)

The reduction of the Ruhr Pocket and advance to Elbe and Mulde rivers between 5 and 18 April 1945

The first step in realizing Eisenhower's plan was the eradication of the Ruhr Pocket. Even before the encirclement had been completed, the Germans in the Ruhr had begun making attempts at a breakout to the east. All had been unceremoniously repulsed by the vastly superior Allied forces. Meanwhile, the 9th and 1st Armies began preparing converging attacks using the east-west Ruhr River as a boundary line. The 9th Army's XVI Corps—which had taken up position north of the Ruhr area after crossing the Rhine—would be assisted in its southward drive by two divisions of the XIX Corps, the rest of which would continue to press eastward along with the XIII Corps. South of the Ruhr River, the 1st Army's northward attack was to be executed by the XVIII Airborne Corps, which had been transferred to Hodges after Operation Varsity, and the III Corps, with the 1st Army's V and VII Corps continuing the offensive east. The 9th Army's sector of the Ruhr Pocket—although only about 1/3 the size of the 1st Army's sector south of the river—contained the majority of the densely urbanized industrial area within the encirclement. The 1st Army's area, on the other hand, was composed of rough, heavily forested terrain with a poor road network.[38]

By 1 April, when the trap closed around the Germans in the Ruhr, their fate was sealed. In a matter of days they would all be killed or captured. On 4 April, the day it shifted to Bradley's control, the 9th Army began its attack south toward the Ruhr River. In the south, the 1st Army's III Corps launched its strike on the 5th, and the XVIII Airborne Corps joined in on the 6th, both pushing generally northward. German resistance, initially rather determined, dwindled rapidly. By 13 April, the 9th Army had cleared the northern part of the pocket, while elements of the XVIII Airborne Corps′ 8th Infantry Division reached the southern bank of the Ruhr, splitting the southern section of the pocket in two. Thousands of prisoners were being taken every day; from 16–18 April, when all opposition ended and the remnants of German Army Group B formally surrendered, German troops had been surrendering in droves throughout the region. Army Group B commander Walther Model committed suicide on 21 April.[39]

The final tally of prisoners taken in the Ruhr reached 325,000, far beyond anything the Americans had anticipated. Tactical commanders hastily enclosed huge open fields with barbed wire creating makeshift prisoner of war camps, where the inmates awaited the end of the war and their chance to return home. Also looking forward to going home, tens of thousands of freed forced laborers and Allied prisoners of war further strained the American logistical system.[39]

U.S. 12th Army Group prepares its final thrust

Meanwhile, the remaining Allied forces north, south, and east of the Ruhr had been adjusting their lines in preparation for the final advance through Germany. Under the new concept, Bradley's 12th U.S. Army Group would make the main effort, with Hodges′ 1st Army in the center heading east for about 130 mi (210 km) toward the city of Leipzig and the Elbe River. To the north, the 9th Army's XIX and XIII Corps would also drive for the Elbe, toward Magdeburg, about 65 mi (105 km) north of Leipzig, although the army commander, General Simpson, hoped he would be allowed to go all the way to Berlin. To the south, Patton's 3rd Army was to drive east to Chemnitz, about 40 mi (64 km) southeast of Leipzig, but well short of the Elbe, and then turn southeast into Austria. At the same time, General Devers' 6th U.S. Army Group would move south through Bavaria and the Black Forest to Austria and the Alps, ending the threat of any Nazi last-ditch stand there.[40]

On 4 April, as it paused to allow the rest of the 12th U.S. Army Group to catch up, the 3rd Army made two notable discoveries. Near the town of Merkers, elements of the 90th Infantry Division found a sealed salt mine containing a large portion of the German national treasure. The hoard included vast quantities of German paper currency, stacks of priceless paintings, piles of looted gold and silver jewelry and household objects, and an estimated $250,000,000 worth of gold bars and coins of various nations. But the other discovery made by the 3rd Army on 4 April horrified and angered those who saw it. When the 4th Armored Division and elements of the 89th Infantry Division captured the small town of Ohrdruf, a few miles south of Gotha, they found the first concentration camp taken by the western Allies.[41]

U.S. 12th Army Group advances to the Elbe (9 April)

The 4 April pause in the 3rd Army advance allowed the other armies under Bradley's command to reach the Leine River, about 50 mi (80 km) east of Paderborn. Thus all three armies of the 12th U.S. Army Group were in a fairly even north-south line, enabling them to advance abreast of each other to the Elbe. By 9 April, both the 9th and 1st Armies had seized bridgeheads over the Leine, prompting Bradley to order an unrestricted eastward advance. On the morning of 10 April, the 12th U.S. Army Group's drive to the Elbe began in earnest.[41]

The Elbe River was the official eastward objective, but many American commanders still eyed Berlin. By the evening of 11 April, elements of the 9th Army's 2nd Armored Division—seemingly intent on demonstrating how easily their army could take that coveted prize—had dashed 73 mi (117 km) to reach the Elbe southeast of Magdeburg, just 50 mi (80 km) short of the German capital. On 12 April, additional 9th Army elements attained the Elbe and by the next day were on the opposite bank hopefully awaiting permission to drive on to Berlin. But two days later, on 15 April, they had to abandon these hopes. Eisenhower sent Bradley his final word on the matter: the 9th Army was to stay put—there would be no effort to take Berlin. Simpson subsequently turned his troops' attention to mopping up pockets of local resistance.[41]

American tanks in Coburg on 25 April

In the center of the 12th U.S. Army Group, Hodges′ 1st Army faced somewhat stiffer opposition, though it hardly slowed the pace. As its forces approached Leipzig, about 60 mi (97 km) south of Magdeburg and 15 mi (24 km) short of the Mulde River, the 1st Army ran into one of the few remaining centers of organized resistance. Here the Germans turned a thick defense belt of antiaircraft guns against the American ground troops with devastating effects. Through a combination of flanking movements and night attacks, First Army troops were able to destroy or bypass the guns, moving finally into Leipzig, which formally surrendered on the morning of 20 April. By the end of the day, the units that had taken Leipzig joined the rest of the 1st Army on the Mulde, where it had been ordered to halt.[42]

Meanwhile, on the 12th U.S. Army Group's southern flank, the 3rd Army had advanced apace, moving 30 mi (48 km) eastward to take Erfurt and Weimar, and then, by 12 April, another 30 mi (48 km) through the old 1806 Jena Napoleonic battlefield area. On that day, Eisenhower instructed Patton to halt the 3rd Army at the Mulde River, about 10 mi (16 km) short of its original objective, Chemnitz. The change resulted from an agreement between the American and Soviet military leadership based on the need to establish a readily identifiable geographical line to avoid accidental clashes between the converging Allied forces. However, as the 3rd Army began pulling up to the Mulde on 13 April, the XII Corps—Patton's southernmost force—continued moving southeast alongside the 6th U.S. Army Group to clear southern Germany and move into Austria. After taking Coburg, about 50 mi (80 km) south of Erfurt, on 11 April, XII Corps troops captured Bayreuth, 35 mi (56 km) farther southeast, on 14 April.[43]

As was the case throughout the campaign, the German ability to fight was sporadic and unpredictable during the drive to the Elbe-Mulde line. Some areas were stoutly defended while in others the enemy surrendered after little more than token resistance. By sending armored spearheads around hotly contested areas, isolating them for reduction by subsequent waves of infantry, Eisenhower's forces maintained their eastward momentum. A German holdout force of 70,000 in the Harz Mountains—40 mi (64 km) north of Erfurt—was neutralized in this way, as were the towns of Erfurt, Jena, and Leipzig.[43]

U.S. First Army makes first contact with the advancing Soviets (25 April)

The final operations of the Western Allied armies between 19 April and 7 May 1945 and the change in the Soviet front line over this period.

Every unit along the Elbe-Mulde line was anxious to be the first to meet the Red Army. By the last week of April, it was well known that the Soviets were close, and dozens of American patrols were probing beyond the east bank of the Mulde, hoping to meet them. Elements of the 1st Army's V Corps made first contact. At 11:30 on 25 April, a small patrol from the 69th Infantry Division met a lone Soviet horseman in the village of Leckwitz. Several other patrols from the 69th had similar encounters later that day, and on 26 April the division commander, Maj. Gen. Emil F. Reinhardt, met Maj. Gen. Vladimir Rusakov of the Russian 58th Guards Infantry Division at Torgau in the first official link-up ceremony.[43]

25 April is known as Elbe Day.

U.S. 6th Army Group heads for Austria

While the 12th U.S. Army Group made its eastward thrust, General Devers′ 6th U.S. Army Group to the south had the dual mission of protecting the 12th U.S. Army Group's right flank and eliminating any German attempt to make a last stand in the Alps of southern Germany and western Austria. To accomplish both objectives, Lt. Gen. Alexander Patch's 7th Army on Devers′ left was to make a great arc, first driving northeastward alongside Bradley's flank, then turning south with the 3rd Army to take Nuremberg and Munich, ultimately continuing into Austria. The French 1st Army—under General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny—was to attack to the south and southeast, taking Stuttgart before moving to the Swiss border and into Austria.[44]

Initially, the opposition in the 6th U.S. Army Group's sector was stiffer than that facing the 12th U.S. Army Group. The German forces there were simply in less disarray than those to the north. Nevertheless, the 7th Army broke out of its Rhine bridgehead, just south of Frankfurt, on 28 March, employing elements of three corps—the XV Corps to the north, the XXI Corps in the center, and the VI Corps to the south. The XV Corps′ 45th Infantry Division fought for six days before taking the city of Aschaffenburg, 35 mi (56 km) east of the Rhine, on 3 April. To the south, elements of the VI Corps met unexpectedly fierce resistance at Heilbronn, 40 mi (64 km) into the German rear. Despite a wide armored thrust to envelop the enemy defenses, it took nine days of intense fighting to bring Heilbronn fully under American control. Still, by 11 April 7th Army had penetrated the German defenses in depth, especially in the north, and was ready to begin its wheeling movement southeast and south. Thus, on 15 April when Eisenhower ordered Patton's entire 3rd Army to drive southeast down the Danube River valley to Linz, and south to Salzburg and central Austria, he also instructed the 6th U.S. Army Group to make a similar turn into southern Germany and western Austria.[45]

Soldiers of the US 3rd Infantry Division in Nuremberg on 20 April

Advancing along this new axis the Seventh Army's left rapidly overran Bamberg, over 100 mi (160 km) east of the Rhine, on its way to Nuremberg, about 30 mi (48 km) to the south. As its forces reached Nuremberg on 16 April, the Seventh Army ran into the same type of anti-aircraft gun defense that the 1st Army was facing at Leipzig. Only on 20 April, after breaching the ring of anti-aircraft guns and fighting house-to-house for the city, did its forces take Nuremberg.[46]

Following the capture of Nuremberg, the 7th Army discovered little resistance as the XXI Corps′ 12th Armored Division dashed 50 mi (80 km) to the Danube, crossing it on 22 April, followed several days later by the rest of the corps and the XV Corps as well.[46]

Meanwhile, on the 7th Army's right the VI Corps had moved southeast alongside the French 1st Army. In a double envelopment, the French captured Stuttgart on 21 April, and by the next day both the French and the VI Corps had elements on the Danube. Similarly, the 3rd Army on the 6th U.S. Army Group's left flank had advanced rapidly against very little resistance, its lead elements reaching the river on 24 April.[46]

As the 6th U.S. Army Group and the 3rd Army finished clearing southern Germany and approached Austria, it was clear to most observers, Allied and German alike, that the war was nearly over. Many towns flew white flags of surrender to spare themselves the otherwise inevitable destruction suffered by those that resisted, while German troops surrendered by the tens of thousands, sometimes as entire units.[46]

Link-up of U.S. forces in Germany and Italy (4 May)

On 30 April, elements of 7th Army's XV and XXI Corps captured Munich, 30 miles (48 km) south of the Danube, while the first elements of its VI Corps had already entered Austria two days earlier. On 4 May, the 3rd Army's V Corps and XII Corps advanced into Czechoslovakia, and units of the VI Corps met elements of Lieutenant General Lucian Truscott's U.S. 5th Army on the Italian frontier, linking the European and Mediterranean Theaters. Also on 4 May, after a shift in inter-army boundaries that placed Salzburg in the 7th Army sector, that city surrendered to elements of the XV Corps. The XV Corps also captured Berchtesgaden, the town that would have been Hitler's command post in the National Redoubt. With all passes to the Alps now sealed, however, there would be no final redoubt in Austria or anywhere else. In a few days the war in Europe would be over.[47]

British 21st Army Group crosses the Elbe (29 April)

A British tank in Hamburg on 4 May.

While the Allied armies in the south marched to the Alps, the 21st Army Group drove north and northeast. The right wing of the British 2nd Army reached the Elbe southeast of Hamburg on 19 April. Its left fought for a week to capture Bremen, which fell on 26 April. On 29 April, the British made an assault crossing of the Elbe, supported on the following day by the recently reattached XVIII Airborne Corps. The bridgehead expanded rapidly, and by 2 May Lubeck and Wismar, 40–50 miles (64–80 km) beyond the river, were in Allied hands, sealing off the Germans in the Jutland Peninsula.[48]

On the 21st Army Group's left, one corps of the Canadian 1st Army reached the North Sea near the Dutch-German border on 16 April, while another drove through the central Netherlands, trapping the German forces remaining in that country. However, concerned that the bypassed Germans would flood much of the nation and cause complete famine among a Dutch population already near starvation, General Eisenhower approved an agreement with the local enemy commanders to allow the Allies to air-drop food into the country in return for a local ceasefire on the battlefield. The ensuing airdrops, which began on 29 April,[49] marked the beginning of what was to become a colossal effort to put war-torn Europe back together again.[50]

On 6 May, the 1st Armoured Division (Poland) seized the Kriegsmarine naval base in Wilhelmshaven, where General Maczek accepted the capitulation of the fortress, naval base, East Frisian Fleet and more than 10 infantry divisions.

German surrender (8 May)

Final positions of the Allied armies, May 1945.

By the end of April, the Third Reich was in tatters. Of the land still under Nazi control almost none was actually in Germany. With his escape route to the south severed by the 12th Army Group's eastward drive and Berlin surrounded by the Soviets, Adolf Hitler committed suicide on 30 April, leaving to his successor, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, the task of capitulation. After attempting to strike a deal whereby he would surrender only to the Western Allies—a proposal that was summarily rejected—on 7 May Dönitz granted his representative, Alfred Jodl, permission to effect a complete surrender on all fronts. The appropriate documents were signed on the same day and became effective on 8 May. Despite scattered resistance from a few isolated units, the war in Europe was over.[51]

Analysis

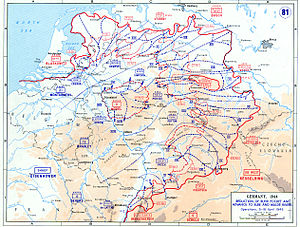

U.S. Airfields in Europe as of 8 May 1945.

By the beginning of the Central Europe Campaign, Allied victory in Europe was inevitable. Having gambled his future ability to defend Germany on the Ardennes offensive and lost, Hitler had no real strength left to stop the powerful Allied armies. The Western Allies still had to fight, often bitterly, for victory. Even when the hopelessness of the German situation became obvious to his most loyal subordinates, Hitler refused to admit defeat. Only when Soviet artillery was falling around his Berlin headquarters bunker did he begin to perceive the final outcome.[51]

The crossing of the Rhine, the encirclement and reduction of the Ruhr, and the sweep to the Elbe-Mulde line and the Alps all established the final campaign on the Western Front as a showcase for Allied superiority in maneuver warfare. Drawing on the experience gained during the campaign in Normandy and the Allied advance from Paris to the Rhine, the Western Allies demonstrated in Central Europe their capability of absorbing the lessons of the past. By attaching mechanized infantry units to armored divisions, they created a hybrid of strength and mobility that served them well in the pursuit warfare through Germany. Key to the effort was the logistical support that kept these forces fueled, and the determination to maintain the forward momentum at all costs. These mobile forces made great thrusts to isolate pockets of German troops, which were mopped up by additional infantry following close behind. The Allies rapidly eroded any remaining ability to resist.[52]

For their part, captured German soldiers often claimed to be most impressed not by American armor or infantry but by the artillery. They frequently remarked on its accuracy and the swiftness of its target acquisition—and especially the prodigious amount of artillery ammunition expended.[53]

In retrospect, very few questionable decisions were made concerning the execution of the campaign. For example, General Patton, the U.S. Third Army commander, potentially could have made his initial Rhine crossing north of Mainz and avoided the losses incurred crossing the Main. Further north the airborne landings during Operation Plunder in support of the 21st Army Group's crossing of the Rhine were probably not worth the risk. But these decisions were made in good faith and had little bearing on the ultimate outcome of the campaign. On the whole, Allied plans were excellent as demonstrated by how rapidly they met their objectives.[53]

Footnotes

^ Szélinger & Tóth 2010, p. 94.

^ MacDonald 2005, p. 322.

^ Includes 25 armored divisions and 5 airborne divisions. Includes 61 American divisions, 13 British divisions, 11 French divisions, 5 Canadian divisions, and 1 Polish division, as well as several independent brigades. One of the British divisions arrived from Italy after the start of the campaign.

^ "Tanks and AFV News", January 27, 2015. Zaloga gives the number of American tanks and tank destroyers as 11,000. The Americans comprised 2/3 of the Allied forces, and other Allied forces were generally equipped to the same standard.

^ ab MacDonald 2005, p. 478.

^ S. L. A. Marshall. ["On Heavy Artillery: American Experience in Four Wars"]. Journal of the US Army War College. Page 10. "The ETO", a term generally only used to refer to American forces in the Western European Theater, fielded 42,000 pieces of artillery; American forces comprised approximately 2/3 of all Allied forces during the campaign.

^ Glantz 1995, p. 304.

^ Zimmerman 2008, p. 277.

^ "Tanks and AFV News", January 27, 2015. Quoting an estimate given in an interview with Steven Zaloga.

^ Alfred Price. Luftwaffe Data Book. Greenhill Books. 1997. Total given for serviceable Luftwaffe strength by April 9, 1945 is 3,331 aircraft. See: Luftwaffe serviceable aircraft strengths (1940–45).

^ Dept of the Army 1953, p. 92.

^ Stacey & Bond 1960, p. 611.

^

- US General George Marshall estimated about 263,000 German battle deaths on the Western Front for the period from 6 June 1944 to 8 May 1945, or a longer period (George C Marshall, Biennial reports of the Chief of Staff of the United States Army to the Secretary of War : 1 July 1939-30 June 1945. Washington, DC : Center of Military History, 1996. Page 202).

- West German military historian Burkhart Müller-Hillebrand (Das Heer 1933–1945 Vol 3. Page 262) estimated 265,000 dead from all causes and 1,012,000 missing and prisoners of war on all German battlefronts from Jan 1, 1945 - April 30, 1945. No breakdown of these figures between the various battlefronts was provided.

- US Army historian Charles B. MacDonald (The European Theater of Operations: The Last Offensive, Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington D.C., 1993, page 478) holds that "exclusive of prisoners of war, all German casualties in the west from D-day to V–E Day probably equaled or slightly exceeded Allied losses". In the related footnote he writes the following: "The only specific figures available are from OB WEST for the period 2 June 1941–10 April 1945 as follows: Dead, 80,819; wounded, 265,526; missing, 490,624; total, 836,969. (Of the total, 4,548 casualties were incurred prior to D-day.) See Rpts, Der Heeresarzt im Oberkommando des Heeres Gen St d H/Gen Qu, Az.: 1335 c/d (IIb) Nr.: H.A./263/45 g. Kdos. of 14 Apr 45 and 1335 c/d (Ilb) (no date, but before 1945). The former is in OCMH X 313, a photostat of a document contained in German armament folder H 17/207; the latter in folder 0KW/1561 (OKW Wehrmacht Verluste). These figures are for the field army only, and do not include the Luftwaffe and Waffen-SS. Since the Germans seldom remained in control of the battlefield in a position to verify the status of those missing, a considerable percentage of the missing probably were killed. Time lag in reporting probably precludes these figures' reflecting the heavy losses during the Allied drive to the Rhine in March, and the cut-off date precludes inclusion of the losses in the Ruhr Pocket and in other stages of the fight in central Germany."

- German military historian Rüdiger Overmans (Deutsche militärische Verluste im Zweiten Weltkrieg, Oldenbourg 2000, pp.265-272) maintains, based on extrapolations from a statistical sample of the German military personnel records.(see German casualties in World War II), that the German armed forces suffered 1,230,045 deaths in the "Final Battles" on the Eastern and Western Fronts from January to May 1945. This figure is broken down as follows (p. 272): 401,660 killed, 131,066 dead from other causes, 697,319 missing and presumed dead. According to Overmans the figures are calculated at "todeszeitpunkt" the point of death, which means the losses occurred between January to May 1945. The number of POW deaths in Western captivity calculated by Overmans, based on the actual reported cases is 76,000 (p. 286). Between 1962 and 1974 by a German government commission, the Maschke Commission put the figure at 31,300 in western captivity.(p. 286) Overmans maintains (pp. 275, 279) that all 1,230,045 deaths occurred during the period from January to May 1945. He states that there is not sufficient data to give an exact breakout of the 1.2 million dead in the final battles (p.174). He did however make a rough estimate of the allocation for total war losses of 5.3 million; 4 million (75%) on the Eastern front, 1 million (20%) in the West and 500,000 (10%) in other theaters. Up until Dec. 1944 losses in the West were 340,000, this indicates losses could be 400,000 to 600,000 deaths in the Western theater from January to May 1945 (p.265). Overmans does not consider the high losses in early 1945 surprising in view of the bitter fighting, he notes that there were many deaths in the Ruhr pocket (p.240) According to Overmans the total dead including POW deaths, in all theaters from Jan-May 1945 was 1,407,000 (January-452,000; February-295,000; March-284,000; April-282,000; May-94,000) No breakout by theater for these losses is provided.(p.239)

^ Rüdiger Overmans, Soldaten hinter Stacheldraht. Deutsche Kriegs-gefangene des Zweiten Weltkrieges. Ullstein Taschenbuchvlg., 2002. p.273 During the period January to March 1945 the POW's held Western Allies increased by 200,000; During the period April to June 1945 the number increased to 5,440,000. These figures do not include POWs that died or were released during this period. (see Disarmed Enemy Forces).

^ Zaloga & Dennis 2006, p. 88.

^ Hastings 2005, p. 465.

^ Bedessem 1996, p. 3.

^ Bedessem 1996, pp. 3–6.

^ abcd Bedessem 1996, p. 6.

^ ab Keegan 1989, p. 182.

^ Wendel, Marcus. "Heer". Axis History Factbook..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abc Bedessem 1996, p. 7.

^ Baker 2004, pp. 38–39.

^ ab Bedessem 1996, p. 8.

^ abc Bedessem 1996, p. 9.

^ Bedessem 1996, pp. 9–10.

^ Bedessem 1996, p. 10.

^ abcd Bedessem 1996, p. 11.

^ Chapter 21: From the Rhine to the Elbe

^ abcd Bedessem 1996, p. 12.

^ abc Bedessem 1996, p. 13.

^ abcd Bedessem 1996, p. 16.

^ abc Bedessem 1996, p. 17.

^ abc Bedessem 1996, p. 20.

^ abc Bedessem 1996, p. 21.

^ Universal Newsreel staff 1945.

^ Bedessem 1996, p. 22.

^ Bedessem 1996, pp. 22–23.

^ ab Bedessem 1996, p. 23.

^ Bedessem 1996, pp. 23,26.

^ abc Bedessem 1996, p. 26.

^ Bedessem 1996, p. 27.

^ abc Bedessem 1996, p. 30.

^ Bedessem 1996, p. 31.

^ Bedessem 1996, pp. 31–32.

^ abcd Bedessem 1996, p. 32.

^ Bedessem 1996, pp. 32–33.

^ Bedessem 1996, p. 33.

^ RAF staff 2005, April 1945.

^ Bedessem 1996, pp. 33–34.

^ ab Bedessem 1996, p. 34.

^ Bedessem 1996, pp. 34–35.

^ ab Bedessem 1996, p. 35.

References

Baker, Anni P. (2004). American Soldiers Overseas: The Global Military Presence. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. pp. 38–39. ISBN 0-275-97354-9.

Bedessem, Edward M. (1996). Central Europe, 22 March – 11 May 1945. CMH Online bookshelves: The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. Washington, D.C.: US Army Center of Military History. ISBN 0-16-048136-8. CMH Pub 72-36.

"Army Battle Casualties and Nonbattle Deaths in World War II". Combined Arms Research Library, Department of the Army. 25 June 1953. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

Glantz, David (1995). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army stopped Hitler. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0899-0.

Hastings, Max (2005). Armageddon: The Battle for Germany, 1944–1945. Vintage. ISBN 0-375-71422-7.

Keegan, John, ed. (1989). The Times Atlas of the Second World War. London: Times Books. ISBN 0-7230-0317-3.

MacDonald, C (2005). The Last Offensive: The European Theater of Operations. University Press of the Pacific. p. 322.

RAF staff (6 April 2005). "Bomber Command: Campaign Diary: April–May 1945". RAF History – Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. Archived from the original on 6 July 2007.

Stacey, Colonel Charles Perry; Bond, Major C. C. J. (1960). The Victory Campaign: The Operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945. Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. III. The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery Ottawa. OCLC 256471407.

Szélinger, Balázs; Tóth, Marcell (2010). "Magyar katonák idegen frontokon" [Hungarian soldiers on foreign fronts]. In Duzs, Mária. Küzdelem Magyarországért: Harcok hazai földön (in Hungarian). Kisújszállás: Pannon-Literatúra Kft. p. 94. ISBN 978-963-251-185-6.

Universal Newsreel staff (1945). Video: Allies Overrun Germany Etc. (1945). Universal Newsreel. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

Zaloga, Steve; Dennis, Peter (2006). Remagen 1945: Endgame Against the Third Reich. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-249-0.

Zimmerman, John (2008). Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg (Vol. 10 Part 1). Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. ISBN 978-3-421-06237-6.

Attribution:

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Government document "Central Europe, 22 March – 11 May 1945, by Edward M. Bedessem".

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Government document "Central Europe, 22 March – 11 May 1945, by Edward M. Bedessem".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Western Allied invasion of Germany. |