Flemish Movement

Flemish flag, as used by the Flemish Movement.

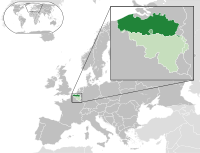

The Flemish Movement (Dutch: Vlaamse Beweging) is the political movement for greater autonomy of the Belgian region of Flanders, for protection of the Dutch language, for the overall protection of Flemish culture and history, and in some cases, for splitting from Belgium and forming an independent state.

The Flemish Movement's moderate wing was for a long time dominated by the Volksunie ("People's Union"), a party that from its onset in 1954 until its collapse in 2002, greatly advanced the Flemish cause although severely criticised by hardliners for being too accommodating. After the Volksunie's collapse, the party's representatives were absorbed by other Flemish parties. Today nearly every Flemish party (except for the far right Vlaams Belang) can be considered part of the moderate wing of the Flemish Movement.[citation needed] This wing has many ties with union and industry organisations, especially with the VOKA (network of the Vlaams Economisch Verbond (VEV, Flemish Economic Union).

The Flemish Movement's right wing is dominated by radical right-wing organizations such as Vlaams Belang, Voorpost, Nationalistische Studentenvereniging (Nationalist Students Union), and several others. The most radical group on the left side is the socialist and Flemish independentist Flemish-Socialist Movement. The militant wing also still comprises several moderate groups such as the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA, Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie), and several extra-parliamentary organisations, many of which are represented in the Overlegcentrum van Vlaamse Verenigingen (OVV, Consultation Centre of Flemish Associations). The most important of these is the Vlaamse Volksbeweging (VVB, Flemish People's Movement).

Contents

1 Internal trends

1.1 Separatists

1.2 Confederalists

1.3 Federalists

1.4 Orangists

2 History

2.1 Early roots

2.2 Belgian Independence

2.3 French Flanders

2.4 A call for change

2.5 World War I

2.6 Post World War I

2.7 World War II

2.8 Post War

2.9 Language border

2.10 Present day

2.11 Transfers

2.12 Current Belgian politics

3 Opinion polling

4 See also

5 References

5.1 Footnotes

5.2 Notations

Internal trends

Separatists

Today[when?], the militant wing of the Flemish Movement generally advocates the foundation of an independent Flemish republic, separating from Wallonia. The rightist parties Vlaams Belang and N-VA (the largest party in the Flemish Parliament as of 2014) support this view.[citation needed] A part of this militant wing also advocates reunion with the Netherlands. This view is shared with several Dutch right-winged activists and nationalists, as well as some mainstream politicians both in the Netherlands and Flanders (such as Louis Tobback, the mayor of Leuven or former minister of defence and Eurocommissioner Frits Bolkestein).[1]

Confederalists

The liberal List Dedecker, as well as several representatives of important Flemish parties belonging to the moderate wing, including the Christian Democratic and Flemish (CD&V) party, the Flemish Liberals and Democrats (VLD) party, and, to a lesser extent, the Different Socialist Party (SP.A), prefer a confederal organisation of the Belgian state over the current federal organisation. Such a scheme would make the Flemish government responsible for nearly all aspects of government,[citation needed] whereas some important aspects of government are currently the responsibility of the Belgian federal government. The Belgian capital of Brussels would remain a city where both Dutch-speaking and French-speaking citizens share equal rights.[citation needed]

As of 2010, the confederalist parties make up more than half of the Flemish Parliament, which combined with the separatist parties, would result in about 80% of the Flemish Parliament (and at least this much of the Flemish part of the Belgian Federal Parliament) occupied by parties who wish to see Flanders obtaining greater autonomy than is the case today.

Federalists

Several representatives of the SP.A and, to a lesser extent, the CD&V and VLD parties, prefer an improved federal organisation of the Belgian state over a confederal one. This view is shared with several social and cultural organisations such as the Vermeylenfonds (Vermeylen Foundation) or Willemsfonds, with labor unions, and with mutual health insurance organisations. The advocates of this view hope to improve the Belgian institutions so that they work correctly.

Orangists

After the secession of Belgium in 1830, the Orangist sentiment in Flanders for a time sought the restoration of the United Kingdom under the house of Orange. Some of the most prominent Flemish Orangists were Jan Frans Willems and Hippolyte Metdepenningen. This sentiment inspired the later Greater Netherlands movement, although that movement was not all monarchist. At present there is only little public support in Flanders (mainly around Flemish-nationalistic parties and the Algemeen-Nederlands Verbond), so there is hardly any public support for the house of Orange. A confederate state made out of these two nations is the only idea that has gained wider support.

History

Jan Frans Willems

Early roots

In 1788 Jan Baptist Chrysostomus Verlooy (1747–1797), a jurist and politician from the Southern Netherlands, wrote an essay titled Verhandeling op d'Onacht der moederlycke tael in de Nederlanden[2] (Essay on the disregard of the native language in the Low Countries), the first sign of life of the Flemish movement: a plea for the native language, but also for freedom and democracy.

Belgian Independence

When the Congress of Vienna created the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, with Protestant Willem I its king, he declared Dutch to be the only official language in all the newly created country. Wallonia, as well as the Catholic clergy and the bourgeoisie in Brussels and Flanders, spoke mainly French, causing unbalanced representation in the Dutch Parliament.

On October 4, 1830, Belgian separatists who were mainly French speaking declared the independence of Belgium from the Netherlands. The Flemish provinces were subordinated by a Belgian army consisting mainly of volunteers from Wallonia, supported by French troops. For example, Ghent was taken by the French Count Pontécoulant with volunteers from Brussels and Paris; Antwerp by Generals De Parent, Mellinet and Niellon.[citation needed]

Large Flemish cities like Ghent and Antwerp were opposed to separation for economic reasons. They had to deal with rebellious workers who mostly choose the side of the Orangists due to poor harvests. This was, however, more an act of discontent than an act of rejecting separatism. In Bruges, for instance, they opposed the separatists who had already taken power in that city. Three years after the separation Orangist parties gained a majority during the municipal elections in some of the aforementioned cities.[citation needed]

French Flanders

Upon Belgium becoming an independent state from the Netherlands, there was an (administrative) reaction against the Dutch and their language. In an attempt to remove Dutch from the new country, Belgian officials declared that the only official language in Belgium now was French. The Administration, Justice System, and higher education (apart from elementary schools in Flanders) all functioned in the French language.[3] Even Brussels, the capital where more than 95% of the population spoke Dutch, lacked a formal, state-sanctioned Flemish school of higher education.[4] The consequence was that every contact with the government and justice was conducted in French. This led to a number of erroneous legal judgements where innocent people received the death penalty because they were not able to verbally defend themselves at trials.[5]

The French-speaking Belgian government succeeded in removing the Dutch language from all levels of government more quickly in Brussels than in any other part of Flanders.[6] Because the administration was centered in Brussels, more and more French-speaking officials took up residency there. Education in Brussels was only in French which led to a surplus of young, unskilled and uneducated Flemish men. Dutch was hardly taught in the French schools.[7] For example: Dutch was worth 10 points in French schools, but drawing earned 15 points.[3] Today 16% of Brussels is Dutch-speaking, whereas in 1830 it was over 95%.[8]

The French-speaking bourgeoisie showed very little respect for the Flemish portion of the population. Belgium's co-founder, Charles Rogier, wrote in 1832 to Jean-Joseph Raikem, the minister of justice:

"Les premiers principes d'une bonne administration sont basés sur l'emploi exclusif d'une langue, et il est évident que la seule langue des Belges doit être le français. Pour arriver à ce résultat, il est nécessaire que toutes les fonctions civiles et militaires soient confiées à des Wallons et à des Luxembourgeois; de cette manière, les Flamands, privés temporairement des avantages attachés à ces emplois, seront contraints d'apprendre le français, et l'on détruira ainsi peu à peu l'élément germanique en Belgique."[8]

"The first principles of a good administration are based upon the exclusive use of one language, and it is evident that the only language of the Belgians should be French. In order to achieve this result, it is necessary that all civil and military functions are entrusted to Walloons and Luxemburgers; this way, the Flemish, temporarily deprived of the advantages of these offices, will be constrained to learn French, and we will hence destroy bit by bit the Germanic element in Belgium."

In 1838, another co-founder, senator Alexandre Gendebien, even declared that the Flemish were "one of the more inferior races on the Earth, just like the negroes".[9]

The economic heart of Belgium in those days was Flanders.[10] However, Wallonia would soon take the lead due to the Industrial Revolution. The Belgian establishment deemed it unnecessary to invest in Flanders and no less than 80% of the Belgian GNP between 1830 and 1918 went to Wallonia.[11] This had as a consequence that Wallonia had a surplus of large coal mines and iron ore facilities, while Flanders, to a large extent, remained a rural, farming region. When Belgium became independent, the economy of Flanders was hard hit. Antwerp was now almost impossible to reach by ships (The Scheldt River was blocked by the Netherlands) and foreign trade was drastically affected. The prosperous textile industry of Ghent lost a major portion of its market to Amsterdam.[12]

A call for change

Bust of Hugo Verriest in Roeselare, Belgium.

It was decades after the Belgian revolution that Flemish intellectuals such as Jan Frans Willems, Philip Blommaert, Karel Lodewijk Ledeganck, Ferdinand Augustijn Snellaert, August Snieders, Prudens van Duyse, and Hendrik Conscience began to call for recognition of the Dutch language and Flemish culture in Belgium. This movement became known as the Flemish Movement, but was more intellectual than social, with contributors such as the poets Guido Gezelle, Hugo Verriest, and Albrecht Rodenbach.

Cultural organizations promoting the Dutch language and Flemish culture were founded, such as the Willemsfonds in 1851, and the Davidsfonds in 1875. The first Vlaemsch Verbond (Constant Leirens, Ghent) and the Nederduitse Bond, were founded in 1861. The Liberale Vlaemsche Bond was founded in 1867. Writers such as Julius de Geyter and Max Rooses were active in the Nederduitse Bond. On 26 September 1866, Julius de Geyter founded the Vlaamsche Bond in Antwerp. The Flemish weekly magazine Het Volksbelang, founded by Julius Vuylsteke, appeared for the first time on 12 January 1867.

In 1861, the first Flemish political party, the Meetingpartij was founded in Antwerp, by radical liberals, Catholics and Flamingants (Jan Theodoor van Rijswijck, J. De Laet and E. Coremans), and it existed until 1914. In 1888, Julius Hoste Sr. founded the moderate liberal Flemish newspaper Het Laatste Nieuws, to support the Flemish Movement in Brussels. In 1893, the Flemish priest Adolf Daens, founded the Christene Volkspartij, which would cause a radicalization and democratization of the Catholic party. The first Flemish political success was the passing of the Gelijkheidswet (Equality law) in 1898 that for the first time recognized Dutch as equal to French in judicial matters (legal documents).

World War I

The liberal politician Louis Franck, the Roman Catholic Frans Van Cauwelaert and the socialist Camille Huysmans (together they were called the three crowing cocks) worked together for the introduction of Dutch at Ghent University. In 1911 the proposal by Lodewijk De Raet to this end was accepted, though it would not be implemented until 1930. With the coming of the 20th century the Flemish Movement became more radical and during World War I some activists welcomed the occupiers as "liberating Germanic brothers". The young Marnix Gijsen and the poet Paul van Ostaijen were involved in this activist movement during the war. The Germans did indeed help out their "Germanic brothers" by setting Dutch as the sole administrative language and by creating the Dutch language Von Bissing University in Ghent. Such steps were dictated by the German tactics of taking advantage of the Flemish-Walloon animosity in order to further Germany's own aims and to boost the occupying power's position known as the Flamenpolitik. With German support, Flemish activists formed a regional government, known as the Raad van Vlaanderen (RVV) which declared Flemish autonomy in December 1917.

Most of the Flemish population disapproved of those who collaborated with the German occupiers[citation needed]. The language reforms implemented by the Germans during occupation did not remain in place after the defeat of Germany. The collaboration and subsequent prosecution of certain leaders of the Flemish Movement did not produce a climate congenial to compromise.

Post World War I

The Flemish Movement became more socially oriented through the Frontbeweging (Front Movement), an organization of Flemish soldiers who complained about the lack of consideration for their language in the army, and in Belgium in general, and harbored pacifistic feelings. The Frontbeweging became a political movement, dedicated to peace, tolerance and autonomy (Nooit Meer Oorlog, Godsvrede, Zelfbestuur). A yearly pilgrimage to the IJzertoren is still held to this day. The poet Anton van Wilderode wrote many texts for this occasion.

Many rumours arose regarding the treatment of Flemish soldiers in World War I, though Flemish historians debunked many of these. One such rumour is that many Dutch-speaking soldiers were slaughtered because they could not understand orders given to them in French by French speaking officers. Whether a disproportionate number of Flemish died in the war compared to Walloons, is to this day being disputed. It is clear however, that the Belgian army de facto had only French as the official language. The phrase "et pour les Flamands, la meme chose" originated in this environment also, allegedly being used by the French-speaking officers to "translate" their orders into Dutch. It literally means "and for the Flemish, the same thing", which adds insult to injury for Flemish soldiers not understanding French.

Another source of further frustration was the Belgian royal family's poor knowledge of Dutch. King Albert I enjoyed some popularity in the early ages of the war, because he was a proponent of the bilingual status of Flanders – even though Wallonia was monolingual French, because he declared his oath to be king in both French and Dutch, and because he gave a speech at the start of the war in Dutch, referring to the Battle of the Golden Spurs. In the last years of the war however, it became clear that the only wish of the king was to keep his country peaceful, and not to give the Flemish the rights the French-speaking establishment denied them.

In the 1920s the first Flemish nationalist party was elected. In the 1930s the Flemish Movement grew ever larger and Dutch was recognized for the first time as the sole language of Flanders. In 1931, Joris Van Severen founded the Verbond van Dietse Nationaal-Solidaristen Verdinaso, a fascist movement in Flanders.

World War II

During World War II, Belgium was once again occupied by Germany. The Third Reich enacted laws to protect and encourage the Dutch language in Belgium and, generally, to propagate ill-feelings between Flemings and Francophones, e.g. by setting free only Flemish prisoners-of-war (see Flamenpolitik). The Nazis had no intentions of allowing the creation of an independent Flemish state or of a Greater Netherlands, and instead desired the complete annexation of not only Flanders (which they did de jure during the war through the establishment of a "Reichsgau Flandern" in late 1944), but all of the Low Countries as "racially Germanic" components of a Greater Germanic Reich.[13] Most[who?] Flemish nationalists embraced collaboration as a means to more autonomy. Because of this collaboration by a few, after the war being part of the Flemish movement was associated with having collaborated with the enemy.

Post War

While the Vermeylenfonds had been founded in 1945, the Flemish Movement lay dormant for nearly 20 years following the Second World War. In the 1960s the Flemish movement once more gathered momentum and, in 1962, the linguistic borders within Belgium were finally drawn up with Brussels being designated as a bilingual city. Also, in 1967 an official Dutch version of the Belgian Constitution was adopted.[14] For more than 130 years, the Dutch version of the Belgian constitution had been only a translation without legal value.

The late 1960s saw all major Belgian political parties splitting up into either Flemish or Francophone wings. It also saw the emergence of the first major nationalist Flemish party, the Volksunie (Popular Union, but not in a communist sense). In 1977 more radical far right-wing factions of the Volksunie became united and, together with earlier far right nationalist groups, formed Vlaams Blok. This party eventually overtook the Volksunie, only to be forced later, on the grounds of a discrimination conviction, to change its name to Vlaams Belang. It has become an important right-wing party of the Flemish Movement.

Language border

During the existence of Belgium more and more Dutch-speaking regions have become French-speaking regions; for example, Mouscron (Moeskroen), Comines (Komen), and particularly Brussels (see Francization of Brussels). Every ten years the government counted the people who spoke Dutch and those who spoke French. These countings always favoured the French-speaking part of Belgium.[3] In 1962 the Linguistic Border was drawn. In order to do so, a complicated compromise with the French-speakers was orchestrated: Brussels had to be recognised as an autonomous and bilingual region while Flanders and Wallonia remained monolingual regions. The French-speakers also demanded that in certain regions where there was a minority of more than 30% French-speaking or Dutch-speaking people; there would be language facilities. This means that these people can communicate with the government in their birth language.

Present day

The Flemish saw these facilities as a measure of integration to another language, as opposed to viewing it as a recognition of a permanent linguistic minority. The French-speaking people, however, saw these language facilities as an acquired right, and a step for an eventual addition to the bilingual region of Brussels, even though that would be unconstitutional.[15] As a result, the amount of French-speaking people in these regions (mostly around Brussels) did not decline, and contain a growing majority of French-speaking Belgians, even though they reside in the officially monolingual Flanders. This "frenchification" is considered frustrating by the Flemish Movement and a reason for a call to separate.

The situation is intensified due to a lack of Dutch language classes in the French-speaking schools.[16]

Transfers

Since the 1960s and continuing into the present time, Flanders is significantly richer than Wallonia. Based on population[17] and GDP [18] figures for 2007, GDP per capita in that year was 28286 € (38186 $) in Flanders and 20191 € (27258 $) in Wallonia. Although equalization payments between richer and poorer regions are common in federal states, the amount, the visibility and the utilization of these financial transfers are a singularly important issue for the Flemish Movement. A study by the University of Leuven[19] has estimated the size of the annual transfers from Flanders to Wallonia and Brussels in 2007 at 5.7 billion euros. If the effect of interest payments on the national debt is taken into account the figure could be as high as 11.3 billion euros or more than 6% of Flemish GDP.[20][21] Flemish criticism is not limited to the size of the transfers but also extends to the lack of transparency and the presumed inability or unwillingness of the recipients to use the money wisely and thus close the economic gap with Flanders. Although no longer relevant in the current economic context, the discussion is often exacerbated by the historic fact that even in the 19th century, when Flanders was much the poorer region, there was a net transfer from Flanders to Wallonia; this was mainly because of relatively heavier taxation of agriculture than of industrial activity.[22]

The tax system was never adjusted to reflect the industrial affluence of Wallonia, which led to an imbalance in tax revenue placing Flanders (average for 1832–1912 period: 44% of the population, 44% of total taxes) at a disadvantage compared with Wallonia (38% of population, 30% of taxes).[23][neutrality is disputed]

Current Belgian politics

As a result of escalating internal conflicts the Volksunie ceased to exist in 2000, splitting into two new parties: Spirit and N-VA (Nieuwe Vlaamse Alliantie, New Flemish Alliance). Both parties tried their luck in cartel with a bigger party, N-VA allying with the Christian Democrats of CD&V, and Spirit with the Flemish socialists of SP.a.

The cartel CD&V – N-VA emerged as the clear winner of the Belgian general election in June 2007 on a platform promising a far-reaching reform of the state. However, coalition negotiations with the French-speaking parties, who rejected any reform, proved extremely difficult. When the CD&V leader Yves Leterme was eventually able to form a government, his reform plans had been greatly diluted and with the onset of the financial crisis in the autumn of 2008 they were shelved completely. This led N-VA to break up the cartel in September 2008, withdrawing its parliamentary support for the federal government (which was thus left without a parliamentary majority in Flanders, a situation that is not unconstitutional but has been deemed undesirable by politicians and constitutional experts).

The role of Spirit, which represented the more left-leaning part of the former Volksunie, gradually declined. After a series of defections, two unsuccessful attempts to broaden its appeal (each time accompanied by a name change) and ending far below the 5% threshold in the Flemish regional elections of 2009, what was left of the party merged with Groen! (the Flemish green party) at the end of 2009.

In the Belgian general election of June 2010, N-VA became the leading party in Flanders and even in Belgium as a whole, polling 28% of the Flemish vote, dwarfing the senior partner of their former cartel, CD&V, which ended at an all-time low of 17.5%.[24] The enormous growth of N-VA is generally explained as caused by an influx of "moderate" Flemish voters who do not support the party's eventual aim of Flemish independence but do want consistent and far-reaching reforms with greater autonomy for the regions, something they no longer trust the traditional parties to be able to achieve.[25] On the Walloon side, the Parti Socialiste (PS), led by Elio Di Rupo, received an even stronger electoral mandate with 37% of the vote. After the election, coalition negotiations started with seven parties: N-VA, CD&V, SP.a and Groen! on the Flemish side, and PS, CDH (nominally Christian Democrat but very much left of centre) and the green party Ecolo on the Francophone side. The talks soon ran into serious difficulties, mainly because of the totally opposed objectives of the two victors: the N-VA economically conservative but with a radical constitutional agenda, the PS socialist and very reluctant to agree to any significant reform of the state. The ensuing deadlock led to an 18-month government formation crisis. In the end, a coalition was formed by CD&V, SP.a, Open VLD on the Flemish side, and PS, CDH and MR on the Walloon side. This coalition however does not contain a majority of the Flemish representatives, with only 43 of 88 Flemish seats supporting it. This situation has never happened since the split of the political parties into Flemish and Walloon wings, and it is unclear how the Flemish voters will show support for this coalition in the next elections.

Opinion polling

In June 2006 a poll published by VRT found that 44% percent of respondents support Flemish independence.[26]

See also

- Burgundian Netherlands

- Dietsland

- Flemish literature

- French Flemish

- Partition of Belgium

- Politics of Flanders

- Seventeen Provinces

- Walloon movement

References

Footnotes

^ Louis Tobback's opinion can be read in knack.rnews.be, Frits Bolkestein's in fritsbolkestein.com

^ Van der Wal, Marijke (1992) Geschiedenis van het Nederlands [History of Dutch] (in Dutch), Utrecht, Het Spectrum, p. 379, .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 90 274 1839 X.

^ abc De Schryver, Reginald (1973), Encyclopedie van de Vlaamse Beweging [Encyclopedia of the Flemish Movement] (in Dutch), Leuven: Lannoo, ISBN 90-209-0455-8

^ "Over het Brussels Nederlandstalig onderwijs" [about Dutch education in Brussels], VGC (in Dutch), Commission of the Flemish Community, archived from the original on 2012-11-20

^ Vande Lanotte, Johan & Goedertier, Geert (2007), Overzicht publiekrecht [Outline public law] (in Dutch), Brugge: die Keure, p. 23, ISBN 978-90-8661-397-7

^ Fleerackers, J. (1973), Colloqium Neerlandicum:De historische kracht van de Vlaamse beweging in België [Colloqium Neerlandicum:The Historical Power of the Flemish Movement in Belgium] (in Dutch), Digitale Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren

^ Rudi, Janssens (2001), Taalgebruik in Brussel — Taalverhoudingen, taalverschuivingen en taalidentiteit in een meertalige stad [Language Use in Brussels - language-relation, movement and identity in a multilingual city] (PDF) (in Dutch), VUBPress (Vrije Universiteit Brussel), ISBN 90-5487-293-4

^ ab Leclerc, Jacques (2008), Petite histoire de la Belgique et ses conséquences linguistices [Small history of Belgium and their linguistic consequences] (in French), Université Laval

^ Gaus, H. (2007), Alexander Gendebien en de organisatie van de Belgische revolutie van 1830 [Alexander Gendebien and the organisation of the Belgian revolution in 1830] (in Dutch and French)

^ Van Daele, Henri (2005), Een geschiedenis van Vlaanderen [A history of Flanders] (in Dutch), Uitgeverij Lannoo

^ Reynebeau, Marc (2006), Een geschiedenis van België [A history of Belgium] (in Dutch), Lannoo, p. 143

^ Reynebeau, Marc (2006), Een geschiedenis van België [A history of Belgium] (in Dutch), Lannoo, pp. 142–44

^ Rich, Norman (1974). Hitler's War Aims: the Establishment of the New Order. W.W. Norton & Company Inc., New York, pp. 179–80, 195–96.

^ Ethnic structure, inequality and governance of the public sector in Belgium

^ (in Dutch) "Vlaanderen en de taalwetgeving" (Flanders and language legislation), vlaanderen.be (ministerie van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap)

^ Prof. W. Dewachter (2006), De maatschappelijke identiteiten Vlaanderen en Wallonië [The cultural differences between Flanders and Wallonia], archived from the original on 2011-08-12

^ Statbel.fgov.be

^ NBB.be

^ Econ.kuleuven.be

^ (in Dutch) "Geldstroom naar Wallonië bereikt recordhoogte" (Money transfers reach record height), nieuwsblad.be

^ (in Dutch) "Vlaanderen en Wallonië zijn beter af zonder transfers" (Flanders and Wallonia are better off without transfers)

^ Juul Hannes, De mythe van de omgekeerde transfers, retrieved 2008-10-21

^ Filip van Laenen (2002-05-20), Flemish Questions – Flows of money out of Flanders, retrieved 2008-09-04

^ Verkiezingen2010.belgium.be Archived July 9, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

^ (in Dutch) Standaard.be

^ https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/118980/1/ERSA2010_0735.pdf

Notations

- Van geyt et al., The Flemish Movement, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science.1946; 247: 128-130

- Vos Hermans, The Flemish Movement: A Documentary History, 1780–1990, Continuum International Publishing Group – Athlone (Feb 1992),

ISBN 0-485-11368-6

- Clough Shepard B., History of the Flemish Movement in Belgium: A study in nationalism, New York, 1930, 316 pp.

- Ludo Simons (ed.), Nieuwe Encyclopedie van de Vlaamse Beweging, Lannoo, 1998,

ISBN 978-90-209-3042-9

- M. Van Haegendoren, The Flemish movement in Belgium, (J. Deleu) Ons Erfdeel – 1965, nr 1, p. 145

- J. Dewulf, The Flemish Movement: On the Intersection of Language and Politics in the Dutch-Speaking Part of Belgium, Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, vol. 13, issue 1 (Winter/Spring 2012): 23–33.