Green Climate Fund

| |

| |

| Abbreviation | GCF |

|---|---|

| Formation | 2010 |

| Legal status | Active |

| Headquarters | Songdo International Business District, Yeonsu-gu, Incheon, South Korea |

| Website | www.greenclimate.fund |

The Green Climate Fund (GCF) is a fund established within the framework of the UNFCCC as an operating entity of the Financial Mechanism to assist developing countries in adaptation and mitigation practices to counter climate change. The GCF is based in Incheon, South Korea. It is governed by a Board of 24 members and supported by a Secretariat.

The objective of the Green Climate Fund is to "support projects, programmes, policies and other activities in developing country Parties using thematic funding windows".[1] It is intended that the Green Climate Fund be the centrepiece of efforts to raise Climate Finance under the UNFCCC.

According to the Climate & Development Knowledge Network, at the third meeting of the Board in Berlin in March 2013, members agreed on how to move forward with the fund's Business Model Framework (BMF). They identified the need to assess various options for how nations could access the fund, approaches for involving the private sector, plus ways to measure results and ensure requests for monies are country-driven.[2] At the fourth Board meeting in June 2013, Hela Cheikhrouhou, a Tunisian national, was selected to become the Fund's first Executive Director.[3] Cheikhrouhou left the fund in September 2016.[citation needed] Ms. Cheikhrouhou was succeeded by Australian national Howard Bamsey, who took office on 10 January 2017. Mr. Bamsey resigned from his position as Executive Director on 4 July 2018, at the completion of the 20th meeting of the Board which was dominated by "challenging and difficult discussions between Board members"[1] without any climate finance being approved. The position of Executive Director is temporarily observed by Javier Manzanares until a replacement is appointed by the Board.

Contents

1 History

2 Organization

3 Sources of finance

4 Issues

4.1 Fulfilling the Green Climate Fund’s requirements when developing a funding proposal

4.2 Role of the private sector

4.3 Additionality of funds

4.4 A lack of stakeholder involvement

4.5 Failure to ban fossil fuel funding under climate finance

5 Accredited entities

6 References

7 Further reading

8 External links

History

The Copenhagen Accord, established during the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP-15) in Copenhagen mentioned the "Copenhagen Green Climate Fund". The fund was formally established during the 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Cancun as a fund within the UNFCCC framework.[4] Its governing instrument was adopted at the 2011 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 17) in Durban, South Africa.[5]

Organization

During COP-16 in Cancun, the matter of governing the GCF was entrusted to the newly founded Green Climate Fund Board, and the World Bank was chosen as the temporary trustee.[4] To develop a design for the functioning of the GCF, the "Transitional Committee for the Green Climate Fund" was established in Cancun too. The committee met four times throughout the year 2011, and submitted a report to the 17th COP in Durban, South Africa. Based on this report, the COP decided that the "GCF would become an operating entity of the financial mechanism" of the UNFCCC,[6] and that on COP-18 in 2012, the necessary rules should be adopted to ensure that the GCF "is accountable to and functions under the guidance of the COP".[6] Researchers at the Overseas Development Institute state that without this last minute agreement on a governing instrument for the GCF, the "African COP" would have been considered a failure.[7] Furthermore, the GCF Board was tasked with developing rules and procedures for the disbursement of funds, ensuring that these should be consistent with the national objectives of the countries where projects and programmes will be taking place. The GCF Board was also charged with establishing an independent secretariat and the permanent trustee of the GCF.[6]

Sources of finance

The Fund has set itself a goal of raising $100 billion a year by 2020, which is not an official figure for the size of the Fund itself. Uncertainty over where this money would come from led to the creation of a High Level Advisory Group on Climate Financing (AGF) by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon in February 2010. There is no formal connection between AGF and GCF, although its report is one source for debates on "resource mobilisation" for the GCF, an item that will be discussed at the GCF's October 2013 Board meeting.[8] Disputes also remain as to whether the funding target will be based on public sources, or whether "leveraged" private finance will be counted towards the total.[9]

As at 17 May 2017, a total of US$10.3 billion has been pledged, which is mostly meant to cover start-up costs.[10]

The European Commission does not provide funding to the fund. EU member states contribute directly, and by 2016 they have jointly pledged US$4.7 billion, nearly half of the fund's resources.[11]

The lack of pledged funds and potential reliance on the private sector is controversial and has been criticized by developing countries.[12] Though the Green Climate Fund is an important institution for ensuring the implementation of the Paris Agreement, its future financial viability is by no means guaranteed. The USA had pledged $ 3 billion, of which $ 2 billion are outstanding. Since US President Donald Trump has announced his nation’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement in June, this money is unlikely to flow in the next few years. Some observers worry that other major donor countries – including Japan, Britain and Germany – will not make up for the shortfall.[13]

U.S. President Obama committed the US to contributing US$3 billion to the fund. In January 2017, in his final 3 days in office, Obama initiated the transfer of a second $500m installment to the fund, leaving $2 billion owing. U.S. President Donald Trump in his announcement of U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on June 1, 2017, also criticized the Green Climate Fund, calling it a scheme to redistribute wealth from rich to poor countries.[14]

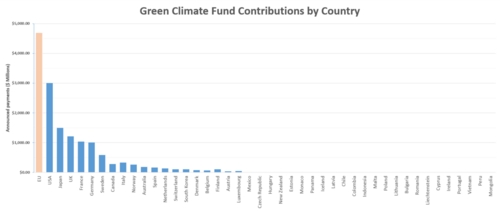

| Country | Announced ($Millions) | Signed ($Millions) | Signed per capita | GDP per capita | Emissions per capita (tonnes of CO2e) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU* | $4,697 | $4,611.90 | NA | NA | NA |

| USA | $3,000 | $3,000 | $9.41 | $55,000 | 17 |

| Japan | $1,500 | $1,500 | $11.80 | $36,000 | 9 |

| UK | $1,211 | $1,211 | $18.77 | $46,000 | 7 |

| France | $1,035 | $1,035 | $15.64 | $43,000 | 5 |

| Germany | $1,003 | $1,003 | $12.40 | $48,000 | 9 |

| Sweden | $581 | $581 | $59.31 | $59,000 | 6 |

| Canada | $277 | $277 | $7.79 | $50,000 | 14 |

| Italy | $334 | $268 | $4.54 | $35,000 | 7 |

| Norway | $258 | $258 | $50.20 | $97,000 | 9 |

| Australia | $187 | $187 | $7.92 | $62,000 | 17 |

| Spain | $161 | $161 | $3.46 | $30,000 | 6 |

| Netherlands | $134 | $134 | $7.94 | $52,000 | 10 |

| Switzerland | $100 | $100 | $12.21 | $85,000 | 5 |

| South Korea | $100 | $100 | $1.99 | $28,000 | 12 |

| Denmark | $71.8 | $71.8 | $12.73 | $61,000 | 7 |

| Belgium | $66.9 | $66.9 | $6.18 | $48,000 | 9 |

| Finland | $107 | $46.4 | $8.49 | $50,000 | 10 |

| Austria | $34.8 | $34.8 | $4.09 | $51,000 | 8 |

| Luxembourg | $46.8 | $33.4 | $58.63 | $111,000 | 21 |

| Mexico | $10.0 | $10.0 | $0.08 | $10,000 | 4 |

| Czech Republic | $5.32 | $5.32 | $0.57 | $20,000 | 10 |

| Hungary | $4.30 | $4.30 | $0.43 | $14,000 | 5 |

| New Zealand | $2.56 | $2.56 | $0.57 | $42,000 | 7 |

| Estonia | $1.30 | $1.30 | $0.99 | $20,000 | 14 |

| Monaco | $1.08 | $1.08 | $28.89 | $163,000 | – |

| Panama | $1.00 | $1.00 | $0.25 | $12,000 | 3 |

| Iceland | $1.00 | $0.50 | $1.55 | $52,000 | 6 |

| Latvia | $0.47 | $0.47 | $0.24 | $16,000 | 4 |

| Chile | $0.30 | $0.30 | $0.02 | $15,000 | 5 |

| Colombia | $6.00 | $0.30 | < $0.01 | $8,000 | 2 |

| Indonesia | $0.25 | $0.25 | < $0.01 | $4,000 | 2 |

| Malta | $0.20 | $0.20 | $0.47 | $23,000 | 6 |

| Poland | $0.11 | $0.11 | < $0.01 | $14,000 | 8 |

| Lithuania | $0.10 | $0.10 | $0.04 | $16,000 | 5 |

| Bulgaria | $0.10 | $0.10 | $0.02 | $8,000 | 7 |

| Romania | $0.10 | $0.10 | < $0.01 | $10,000 | 4 |

| Liechtenstein | < $0.1 | < $0.1 | $1.48 | $135,000 | 1 |

| Cyprus | $0.50 | – | 0 | $27,000 | 7 |

| Ireland | $2.70 | – | 0 | $53,000 | 8 |

| Vietnam | $0.10 | – | 0 | $2,000 | 2 |

| Portugal | $2.68 | – | 0 | $22,000 | 5 |

| Peru | $6.00 | – | 0 | $7,000 | 2 |

| Mongolia | < $0.1 | – | 0 | $4,000 | 7 |

*The EU does not provide direct funding to the GCF, this figure is an aggregate of all EU members' contributions.

Issues

The process of designing the GCF has raised several issues. These include ongoing questions on how funds will be raised,[16] the role of the private sector,[17] the level of "country ownership" of resources,[18] and the transparency of the Board itself.[19] In addition, questions have been raised about the need for yet another new international climate institution which may further fragment public dollars that are put toward mitigation and adaptation annually.[20]

The Fund is also pledged to offer "balanced" support to adaptation and mitigation, although there is some concern amongst developing countries that inadequate adaptation financing will be offered, in particular if the fund is reliant on "leveraging" private sector finance.[21]

The Fund's initial investments have met with mixed responses. The Fund's former director Héla Cheikhrouhou has complained that the Fund is backing too many "business-as-usual types of investment proposals", a view echoed by a number of civil society organizations.[22] But in at least one case it also drew praise for involving local communities in the formulation of an adaptation project, and for incorporating consumer protection into a plan for off-grid solar energy.[23]

Fulfilling the Green Climate Fund’s requirements when developing a funding proposal

While it is relatively easy to tell what a mitigation project or programme is (i.e. its contribution to the reduction of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, and/or whether it increases the capacity of an ecosystem to absorb them), the blurred line between a general development project and an adaptation project has been a contentious issue in the international climate finance debate, including at Green Climate Fund Board meetings, according to a report by the Climate and Development Knowledge Network.[24]

The relevant question is not whether a project is (also) a development project, but whether the project contributes to adaptation (i.e. what the adaptation/additionality argument is). Cross- cutting projects that deliver co-benefits in terms of both mitigation and adaptation are also eligible for funding.[24]

Role of the private sector

One of the most controversial aspects of the GCF concerns the creation of the Fund's Private Sector Facility (PSF). Many of the developed countries represented on the GCF board advocate a PSF that appeals to capital markets, in particular the pension funds and other institutional investors that control trillions of dollars that pass through Wall Street and other financial centers. They hope that the Fund will ultimately use a broad range of financial instruments.[25]

However, several developing countries and non-governmental organizations have suggested that the PSF should focus on "pro-poor climate finance" that addresses the difficulties faced by micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises in developing countries. This emphasis on encouraging the domestic private sector is also written into the GCF's Governing Instrument, its founding document.[26]

Additionality of funds

The Cancun agreements clearly specify that the funds provided to the developing countries as climate finance, including through the GCF, should be "new" and "additional" to existing development aid.[4] The condition of funds having to be new means that pledges should come on top of those made in previous years. As far as additionality is concerned, there is no strict definition of this term, which has already led to serious problems in evaluating the additionality of emission reductions through CDM-projects, leading to counter-productivity, and even fraud.[27][28] While climate finance usually only counts pledges from developed countries, the US$10.3 billion pledged to the GCF also includes some (relatively small) contributions from developing countries.[10]

A lack of stakeholder involvement

Using the money in the right way in order to enforce actual change on the ground is one of the biggest challenges ahead. Many academics argue that, in order to do this in an efficient way, all stakeholders should be involved in the process, instead of using a top-down approach. They point to that fact that, without their input, it is harder to achieve targets set. Moreover, projects often even miss out on their actual purpose.[21][29][30][31][32] A group of researchers associated with the Australian National University,[33] call for the foundation of so-called "National Implementing Entities" (NIE) in each country, that would become responsible for "the implementation of sub-national projects".[33] This would avoid national governments getting too involved, because in the past, they "often hindered the flow of international support to subnational scale reform for sustainable development".[33]

Overall, this view on the need for more stakeholder involvement can be framed within the movement in environmental governance calling for a shift from traditional ways of government to governance.[34] The Climate & Development Knowledge Network is funding a research project that aims to help the GCF Board, by analysing how best to allocate resources among countries. The project will research and present four case studies of how federal or central government money is presently distributed to sub-national entities. Chosen for the diversity in their underlying political systems, these are: China, India, Switzerland, and the USA.[35]

Failure to ban fossil fuel funding under climate finance

At its board meeting in South Korea held in March 2015, the GCF refused an explicit ban on fossil fuel projects. Japan, China, and Saudi Arabia opposed the ban.[36][37]

Accredited entities

List as of 9 March 2016[update]:[38]

Acumen Fund, Inc. (US)

Africa Finance Corporation (Nigeria)

African Development Bank (Côte d'Ivoire)

Agence française de développement (France)

Agency for Agricultural Development of Morocco (Morocco)

Asian Development Bank (Philippines)

Caribbean Community Climate Change Center (Belize)

Centre de Suivi Ecologique (Senégal)

Conservation International Foundation (US)

CAF – Development Bank of Latin America (Venezuela)

Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank (France)

Development Bank of Southern Africa (South Africa)

Deutsche Bank AktienGesellschaft (Germany)

Environmental Investment Fund (Namibia)

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (United Kingdom)

European Investment Bank (Luxembourg)

HSBC Holdings PLC and its subsidiaries (United Kingdom)

Inter-American Development Bank (US)

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and International Development Association (US)

International Finance Corporation (US)

International Union for Conservation of Nature (Switzerland)

Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (Germany)

Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (Ethiopia)

Ministry of Natural Resources (Rwanda)

National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (India)

National Environment Management Authority of Kenya (Kenya)

Peruvian Trust Fund for National Parks and Protected Areas (Peru)

Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (Samoa)

Unidad Para el Cambio Rural (Unit for Rural Change) of Argentina (Argentina)

United Nations Development Programme (US)

United Nations Environment Programme (Kenya)

World Food Programme (Italy)

World Meteorological Organization (Switzerland)

World Wildlife Fund (US)

References

^ UNFCCC. "Transitional Committee for the design of the Green Climate Fund". Retrieved 23 November 2011..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ NEWS: Board members sketch out an operational framework for the Green Climate Fund, Climate & Development Knowledge Network, 27 March 2013

^ Green Climate Fund (press release) (2013), Green Climate Fund Board selects Hela Cheikhrouhou as Executive Director Archived 5 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 31 July 2013

^ abc UNFCCC. "Report of the Conference of the Parties on its sixteenth session, held in Cancun from 29 November to 10 December 2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

^ UNFCCC. "Green Climate Fund - report of the Transitional Committee" (PDF). Retrieved 23 July 2013.

^ abc IISD (13 December 2011). "Summary of the Durban Climate Change Conference: 28 November - 11 December 2011" (PDF). Earth Negotiations Bulletin. 12 (534).

^ Schalatek, L., Stiftung, H., Nakhooda, S. and Bird, N., February 2011, The design of the Green Climate Fund, Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved 7 April 2012

^ UN. "UN Secretary-General's High-level Advisory Group on Climate Change Financing (AGF)". Retrieved 13 December 2011.

^ Institute for Policy Studies (2013), Green Climate Fund, A Glossary of Climate Finance Terms. Retrieved 23 July 2013

^ ab Green Climate Fund, Status of Pledges. Retrieved 17 May 2017

^ http://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/international/finance/index_en.htm

^ Sethi, Nitin (6 December 2011). "A green climate fund but no money at Durban". The Times of India. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

^ Liane Schalatek (21 September 2017). "Signalling effect for global climate finance". D+C, development and cooperation. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

^ Eddy, Somini Sengupta, Melissa; Buckley, Chris (June 1, 2017). "As Trump Exits Paris Agreement, Other Nations Are Defiant". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

^ http://www.greenclimate.fund/partners/contributors/resources-mobilized

^ Wu, Brandon (2013). "Where's the Money? The Elephant in the Boardroom". Huffington Post. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

^ Reyes, Oscar (2013). "Songdo Fallout: is green finance a red herring?". Foreign Policy in Focus. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

^ Carvalho, Annaka Peterson. "3 ways country ownership is being put to the test with climate change funding". Oxfam America. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

^ Godoy, Emilio (2013). "Civil Society Pushes for More Active Participation in Green Climate Fund". Inter Press Service. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

^ Razzouk, Assaad W. (2013). "Why We Should Kill The Green Climate Fund". The Independent. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

^ ab Abbott, K.W., Gartner, D. (2011). "The Green Climate Fund and the Future of Environmental Governance". Earth System Governance Working Paper No. 16. SSRN 1931066.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ Clark, Pilita (6 September 2016). "Green fund investing in the wrong projects, says former chief". Financial times. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

^ Reyes, Oscar (2016). "The Little-Known Fund at the Heart of the Paris Climate Agreement". Foreign Policy in Focus. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

^ ab Green Climate Fund proposal toolkit 2017, Climate & Development Knowledge Network, 31 July 2017

^ Oscar Reyes (2013), Songdo Fallout: is green finance a red herring?, Foreign Policy in Focus. Retrieved 23 July 2013

^ Friends of the Earth USA (2013), Pro-poor Climate Finance: Is There a Role for Private Finance in the Green Climate Fund?, Friends of the Earth USA. Retrieved 24 July 2013

^ Wara, M. W.; Victor, D. G. (April 2008). "A Realistic Policy on International Carbon Offsets" (PDF). PESD Working Paper (74). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

^ International Rivers. "Failed Mechanism: Hundreds of Hydros Expose Serious Flaws in the CDM". Internationalrivers.org. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

^ Easterly, William (May 2008). "Institutions: Top down or Bottom up?" (PDF). The American Economic Review. 98 (2): 95–99. doi:10.1257/aer.98.2.95.

^ Bond, Patrick (2006). "Global Governance Campaigning and mdgs: from top-down to bottom-up anti-poverty work". Third World Quarterly. 27 (2): 339–354. doi:10.1080/01436590500432622.

^ Altieri, Miguel A.; Masera, O. (April 1993). "Sustainable rural development in Latin America: building from the bottom-up". Ecological Economics. 7 (2): 93–121. doi:10.1016/0921-8009(93)90049-c.

^ Richardson, K., Steffen, W. & Liverman, D. (2011). Global Risks, Challenges and Decisions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 524.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ abc van Kerkhoff, Lorrae; Ahmad I.H., Pittock J.; Steffen W. (2011). "Designing the Green Climate Fund: How to Spend $100 Billion Sensibly". Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. 53 (3): 18–31. doi:10.1080/00139157.2011.570644.

^ Evans, James P. (2012). Environmental Governance. London: Routledge. p. 247.

^ NEWS: Guiding allocation of resources from the Green Climate Fund, Climate & development Knowledge Network, 17 December 2012

^ "UN green climate fund can be spent on coal-fired power generation". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

^ Cleantechnica. "Green Climate Fund Can Be Spent To Subsidise Dirty Coal". Cleantechnica. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

^ http://www.greenclimate.fund/documents/20182/114261/20160406_-_GCF_List_of_Accredited_Entities.pdf/e09bb9b3-9730-4adc-bca9-ff32739ecae8

Further reading

- Abbott, K.W., Gartner, D. (2011). "The Green Climate Fund and the Future of Environmental Governance". Earth System Governance Working Paper No. 16.

- ClimateFund.info. "Climate Fund Info".

- Purvis, N. & Stevenson, A. "Climate Negotiations and International Finance".

- van Kerkhoff, Lorrae; Ahmad I.H., Pittock J. and Steffen W. (2011). "Designing the Green Climate Fund: How to Spend $100 Billion Sensibly". Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 53 (3): 18-31.

External links

- Official website