Prime Minister of Australia

| Prime Minister of Australia | |

|---|---|

Commonwealth Coat of Arms | |

Incumbent Scott Morrison since 24 August 2018 | |

| |

| Style |

|

| Member of |

|

| Reports to | Parliament, Governor-General |

| Residence |

|

| Seat | Canberra |

| Appointer | Governor-General of Australia by convention, based on appointee's ability to command confidence in the House of Representatives[2] |

| Term length | At the Governor-General's pleasure contingent on the Prime Minister's ability to command confidence in the lower house of Parliament[3] |

| Inaugural holder | Edmund Barton |

| Formation | 1 January 1901 |

| Deputy | Michael McCormack |

| Salary | $527,852 (AUD) |

| Website | pm.gov.au |

The Prime Minister of Australia (abbreviated PM) is the head of government of Australia. The individual who holds the office is the most senior Minister of the Crown, the leader of the Cabinet. The Prime Minister also has the responsibility of administering the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, and is the chair of the National Security Committee and the Council of Australian Governments. The office of Prime Minister is not mentioned in the Constitution of Australia but exists through Westminster political convention. The individual who holds the office is commissioned by the Governor-General of Australia and at the Governor-General's pleasure subject to the Constitution of Australia and constitutional conventions.

Scott Morrison has held the office of Prime Minister since 24 August 2018. He received his commission after replacing Malcolm Turnbull as the leader of the Liberal Party, the largest party in the Coalition government, following the Liberal Party leadership spill earlier the same day.[4]

Contents

1 Constitutional basis and appointment

2 Powers and role

3 Privileges of office

3.1 Salary

3.2 Allowances

3.3 After office

4 Acting and interim Prime Ministers

5 Former Prime Ministers

6 Ages

7 List and timeline

8 See also

9 Notes

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

Constitutional basis and appointment

Australia |

|---|

|

This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Australia |

Constitution

|

The Crown

|

Executive

|

Legislature

|

Judiciary

|

Elections

|

States and territories

|

Local government

|

Related topics

|

|

Australia's first Prime Minister, Edmund Barton at the central table in the House of Representatives in 1901.

The Prime Minister of Australia is appointed by the Governor-General of Australia under Section 64 of the Australian Constitution, which empowers the Governor-General, as the official representative of the Crown, to appoint government ministers of state on the advice of the Prime Minister and requires them to be members of the House of Representatives or the Senate, or become members within three months of the appointment. The Prime Minister and Treasurer are traditionally members of the House, but the Constitution does not have such a requirement.[5] Before being sworn in as a Minister of the Crown, a person must first be sworn in as a member of the Federal Executive Council if they are not already a member. Membership of the Federal Executive Council entitles the member to the style of The Honourable (usually abbreviated to The Hon) for life, barring exceptional circumstances. The senior members of the Executive Council constitute the Cabinet of Australia.

The Prime Minister is, like other ministers, normally sworn in by the Governor-General and then presented with the commission (letters patent) of office. When defeated in an election, or on resigning, the Prime Minister is said to "hand in the commission" and actually does so by returning it to the Governor-General. In the event of a Prime Minister dying in office, or becoming incapacitated, or for other reasons, the Governor-General can terminate the commission. Ministers hold office "during the pleasure of the Governor-General" (s. 64 of the Constitution of Australia), so theoretically, the Governor-General can dismiss a minister at any time, by notifying them in writing of the termination of their commission; however, their power to do so except on the advice of the Prime Minister is heavily circumscribed by convention.

According to convention, the Prime Minister is the leader of the majority party or largest party in a coalition of parties in the House of Representatives which holds the confidence of the House. Some commentators argue that the Governor-General may also dismiss a Prime Minister who is unable to pass the government's supply bill through both houses of parliament, including the Australian Senate, where the government doesn't normally command the majority, as happened in the 1975 constitutional crisis.[citation needed] Other commentators argue that the Governor General acted improperly in 1975 as Whitlam still retained the confidence of the House of Representatives, and there are no generally accepted conventions to guide the use of the Governor General's reserve powers in this circumstance.[2] However, there is no constitutional requirement that the Prime Minister sit in the House of Representatives, or even be a member of the federal parliament (subject to a constitutionally prescribed limit of three months), though by convention this is always the case. The only case where a member of the Senate was appointed Prime Minister was John Gorton, who subsequently resigned his Senate position and was elected as a member of the House of Representatives.

Despite the importance of the office of Prime Minister, the Constitution does not mention the office by name. The conventions of the Westminster system were thought to be sufficiently entrenched in Australia by the authors of the Constitution that it was deemed unnecessary to detail them.[citation needed] The formal title of the portfolio has always been simply "Prime Minister", except for the period of the Fourth Deakin Ministry (June 1909 to April 1910), when it was known as "Prime Minister (without portfolio)".[6]

If a government cannot get its appropriation (budget) legislation passed by the House of Representatives, or the House passes a vote of "no confidence" in the government, the Prime Minister is bound by convention to immediately advise the Governor-General to dissolve the House of Representatives and hold a fresh election.

Following a resignation in other circumstances or the death of a Prime Minister, the governor-general generally appoints the Deputy Prime Minister as the new Prime Minister, until or if such time as the governing party or senior coalition party elects an alternative party leader. This has resulted in the party leaders from the Country Party (now named National Party) being appointed as Prime Minister, despite being the smaller party of their coalition. This occurred when Earle Page became caretaker Prime Minister following the death of Joseph Lyons in 1939, and when John McEwen became caretaker Prime Minister following the disappearance of Harold Holt in 1967. However in 1941, Arthur Fadden became the leader of the Coalition and subsequently Prime Minister by the agreement of both coalition parties, despite being the leader of the smaller party in coalition, following the resignation of UAP leader Robert Menzies.

Excluding the brief transition periods during changes of government or leadership elections, there have only been a handful of cases where someone other than the leader of the majority party in the House of Representatives was Prime Minister:

Federation occurred on 1 January 1901, but elections for the first parliament were not scheduled until late March. In the interim, an unelected caretaker government was necessary. In what is now known as the Hopetoun Blunder, the governor-general, Lord Hopetoun, invited Sir William Lyne, the premier of the most populous state, New South Wales, to form a government. Lyne was unable to do so and returned his commission in favour of Edmund Barton, who became the first Prime Minister and led the inaugural government into and beyond the election.- During the second parliament, three parties (Free Trade, Protectionist and Labor) had roughly equal representation in the House of Representatives. The leaders of the three parties, Alfred Deakin, George Reid and Chris Watson each served as Prime Minister before losing a vote of confidence.

- As a result of the Labor Party's split over conscription, Billy Hughes and his supporters were expelled from the Labor Party in November 1916. He subsequently continued on as prime minister at the head of the new National Labor Party, which had only 14 members out of a total of 75 in the House of Representatives. The Commonwealth Liberal Party – despite still forming the Official Opposition – provided confidence and supply until February 1917, when the two parties agree to merge and form the Nationalist Party.

- During the 1975 constitutional crisis, on 11 November 1975, the governor-general, Sir John Kerr, dismissed the Labor Party's Gough Whitlam as Prime Minister. Despite Labor holding a majority in the House of Representatives, Kerr appointed the Leader of the Opposition, Liberal leader Malcolm Fraser as caretaker Prime Minister, conditional on the passage of the Whitlam government's Supply bills through the Senate and the calling of an election for both houses of parliament. Fraser accepted these terms and immediately advised a double dissolution. An election was called for 13 December, which the Liberal Party won in its own right (although the Liberals governed in a coalition with the Country Party).

Powers and role

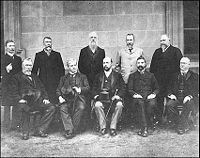

The first Prime Minister of Australia, Edmund Barton (sitting second from left), with his Cabinet, 1901.

Most of the Prime Minister's power derives from being the head of Government.[citation needed] In practice, the Federal Executive Council acts to ratify all executive decisions made by the government and requires the support of the Prime Minister. The powers of the Prime Minister are to direct the Governor General through advice to grant Royal Assent to legislation, to dissolve and prorogue parliament, to call elections and to make government appointments, which the Governor-General follows.

The formal power to appoint the Governor-General lies with the Queen of Australia, on the advice of the Prime Minister, whereby convention holds that the Queen is bound to follow the advice. The Prime Minister can also advise the monarch to dismiss the Governor-General, though it remains unclear how quickly the monarch would act on such advice in a constitutional crisis. This uncertainty, and the possibility of a "race" between the Governor-General and Prime Minister to dismiss the other, was a key question in the 1975 constitutional crisis. Prime Ministers whose government loses a vote of no-confidence in the House of Representatives, are expected to advise the Governor-General to dissolve parliament and hold an election, if an alternative government cannot be formed. If they fail to do this, the Governor-General may by convention dissolve parliament or appoint an alternative government.[7]

The Prime Minister is also the responsible minister for the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, which is tasked with supporting the policy agendas of the Prime Minister and Cabinet through policy advice and the coordination of the implementation of key government programs, to manage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy and programs and to promote reconciliation, to provide leadership for the Australian Public Service alongside the Australian Public Service Commission, to oversee the honours and symbols of the Commonwealth, to provide support to ceremonies and official visits, to set whole of government service delivery policy, and to coordinate national security, cyber, counterterrorism, regulatory reform, cities, population, data, and women's policy.[8] Since 1992, the Prime Minister also acts as the chair of the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), an intergovernmental forum between the federal government and the state governments in which the Prime Minister, the state premiers and chief ministers, and a representative of local governments meet annually.[9]

Privileges of office

Salary

| Effective date | Salary |

|---|---|

| 2 June 1999 | $289,270 |

| 6 September 2006 | $309,270 |

| 1 July 2007 | $330,356 |

| 1 October 2009 | $340,704[10] |

| 1 August 2010 | $354,671[11] |

| 1 July 2011 | $366,366 |

| 1 December 2011 | $440,000 |

| 15 March 2012 | $481,000[12] |

| 1 July 2012 | $495,430[13] |

| 1 July 2013 | $507,338[14] |

| 1 January 2016 | $517,504[15] |

| 1 July 2017 | $527,852[16] |

On 1 July 2017, the Australian Government's Remuneration Tribunal adjusted the Prime Ministerial salary, raising it to its current amount of $527,852,[16] which was equivalent then to ten times the wage of the average Australian. As of May 2018, this made the Australian Prime Minister the highest paid leader in the OECD.[17]

Allowances

Prime Ministers Curtin, Fadden, Hughes, Menzies and Governor-General The Duke of Gloucester 2nd from left, in 1945.

Whilst in office, the Prime Minister has two official residences. The primary official residence is The Lodge in Canberra. Most Prime Ministers have chosen The Lodge as their primary residence because of its security facilities and close proximity to Parliament House. There have been some exceptions, however. James Scullin preferred to live at the Hotel Canberra (now the Hyatt Hotel) and Ben Chifley lived in the Hotel Kurrajong. More recently, John Howard used the Sydney Prime Ministerial residence, Kirribilli House, as his primary accommodation. On her appointment on 24 June 2010, Julia Gillard said she would not be living in The Lodge until such time as she was returned to office by popular vote at the next general election, as she became Prime Minister by replacing an incumbent during a parliamentary term. Tony Abbott was never able to occupy The Lodge during his term (2013–15) as it was undergoing extensive renovations, which continued into the early part of his successor Malcolm Turnbull's term.[18] Instead, Abbott resided in dedicated rooms at the Australian Federal Police College when in Canberra.

During his first term, Rudd had a staff at The Lodge consisting of a senior chef and an assistant chef, a child carer, one senior house attendant, and two junior house attendants. At Kirribilli House in Sydney, there is one full-time chef and one full-time house attendant.[19]

The official residences are fully staffed and catered for both the Prime Minister and their family. In addition, both have extensive security facilities. These residences are regularly used for official entertaining, such as receptions for Australian of the Year finalists.

The Prime Minister receives a number of transport amenities for official business. The Royal Australian Air Force's No. 34 Squadron transports the Prime Minister within Australia and overseas by specially converted Boeing Business Jets and smaller Challenger aircraft. The aircraft contain secure communications equipment as well as an office, conference room and sleeping compartments. The call-sign for the aircraft is "Envoy". For ground travel, the Prime Minister is transported in an armoured BMW 7 Series model. It is referred to as "C-1", or Commonwealth One, because of its licence plate. It is escorted by police vehicles from state and federal authorities.[20]

- Privileges of office

The Lodge

Kirribilli House

Prime Ministerial car

Official aircraft

After office

Politicians, including Prime Ministers, are usually granted certain privileges after leaving office, such as office accommodation, staff assistance, and a Life Gold Pass, which entitles the holder to travel within Australia for "non-commercial" purposes at government expense. In 2017, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said the pass should be available only to former prime ministers, though he would not use it when he was no longer PM.[21]

Only one Prime Minister who had left the Federal Parliament ever returned. Stanley Bruce was defeated in his own seat in 1929 while Prime Minister but was re-elected to parliament in 1931. Other Prime Ministers were elected to parliaments other than the Australian federal parliament: Sir George Reid was elected to the UK House of Commons (after his term as High Commissioner to the UK), and Frank Forde was re-elected to the Queensland Parliament (after his term as High Commissioner to Canada, and a failed attempt to re-enter the Federal Parliament).

Acting and interim Prime Ministers

From time to time Prime Ministers are required to leave the country on government business and a deputy acts in their place during that time. In the days before jet aircraft, such absences could be for extended periods. For example, William Watt was acting Prime Minister for 16 months, from April 1918 until August 1919, when Prime Minister Billy Hughes was away at the Paris Peace Conference,[22] and Senator George Pearce was acting Prime Minister for more than seven months in 1916.[23] An acting Prime Minister is also appointed when the prime minister takes leave. The Deputy Prime Minister most commonly becomes acting Prime Minister in those circumstances.

Three Prime Ministers have died in office – Joseph Lyons (1939), John Curtin (1945) and Harold Holt (1967). In each of these cases, the Deputy Prime Minister (an unofficial office at the time) became an interim Prime Minister, pending an election of a new leader of the government party. In none of these cases was the interim Prime Minister successful at the subsequent election.

Former Prime Ministers

As of November 2018, there are seven living former Australian Prime Ministers.[24]

Bob Hawke In office: 1983–1991 Age: 88 |  Paul Keating In office: 1991–1996 Age: 74 |  John Howard In office: 1996–2007 Age: 79 |  Kevin Rudd In office: 2007–2010; 2013 Age: 61 |  Julia Gillard In office: 2010–2013 Age: 57 |  Tony Abbott, In office: 2013–2015 Age: 61 |  Malcolm Turnbull, In office: 2015–2018 Age: 64 |

The greatest number of living former Prime Ministers at any one time was eight. This has occurred twice:

- Between 7 October 1941 (when John Curtin succeeded Arthur Fadden) and 18 November 1941 (when Chris Watson died), the eight living former Prime Ministers were Bruce, Cook, Fadden, Hughes, Menzies, Page, Scullin and Watson.

- Between 13 July 1945 (when Ben Chifley succeeded Frank Forde) and 30 July 1947 (when Sir Joseph Cook died), the eight living former Prime Ministers were Bruce, Cook, Fadden, Forde, Hughes, Menzies, Page and Scullin.

Of the other Prime Ministers, Ben Chifley died only one year and six months after leaving the Prime Ministership and Alfred Deakin lived another nine years and five months.[25]

All the others who have left office have lived at least another 10 years. Nine of them (Bruce, Cook, Fadden, Forde, Fraser, Gorton, Hughes, Watson, and Whitlam) lived more than 25 years after leaving the office, and all but one of them have survived longer than 30 years (Hughes lived for 29 years and 8 months following service). Bob Hawke, who is still alive, has also lived 25 years beyond the end of his prime ministership.

The longest-surviving was Gough Whitlam, who lived 38 years and 11 months after office, surpassing Stanley Bruce's previous record of 37 years and 10 months after leaving the office.[26]

Ages

Four Australian prime ministers – Forde, Curtin, Menzies, and Hughes – at a meeting of the Advisory War Council in 1940.

The three youngest people when they first became Prime Minister were:

- Chris Watson – 37[27]

- Stanley Bruce – 39[28]

- Robert Menzies – 44[29]

The three oldest people when they first became Prime Minister were:

- John McEwen – 67[30]

- William McMahon – 63[31]

- Malcolm Turnbull – 60

The three youngest people to last leave the office of Prime Minister were:

- Chris Watson – 37

- Arthur Fadden – 46 years 5 months 22 days[32]

- Stanley Bruce – 46 years 6 months 7 days

The three oldest people to last leave the office of Prime Minister were:

- Robert Menzies – 71

- John Howard – 68

- John McEwen – 67

List and timeline

The longest-serving Prime Minister was Sir Robert Menzies, who served in office twice: from 26 April 1939 to 28 August 1941, and again from 19 December 1949 to 26 January 1966. In total Robert Menzies spent 18 years, 5 months and 12 days in office. He served under the United Australia Party and the Liberal Party respectively.

The shortest-serving Prime Minister was Frank Forde, who was appointed to the position on 6 July 1945 after the death of John Curtin, and served until 13 July 1945 when Ben Chifley was elected leader of the Australian Labor Party.

The last Prime Minister to serve out a full government term in the office was John Howard, who won the 2004 election and led his party to the 2007 election, but lost. Since then, the five subsequent Prime Ministers have been either voted out of the office mid-term by the caucuses of their own parties, assumed the office mid-term under such circumstances, or both.

- Parties

Australian Labor Party

Liberal Party of Australia

Australian Country Party

Nationalist Party of Australia

United Australia Party

Commonwealth Liberal Party

National Labor Party

Free Trade Party

Protectionist Party

| No. | Name (birth–death) | Portrait | Party | Term of office | Electorate served | Elections won | Ministry | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sir Edmund Barton (1849–1920) |  | Protectionist | 1 January 1901 | 24 September 1903 | Hunter, NSW, 1901–1903 (resigned) | 1901 | Barton | [33] |

| 2 | Alfred Deakin (1856–1919) |  | Protectionist | 24 September 1903 | 27 April 1904 | Ballaarat, Vic,[Note 1] 1901–1913 (retired) | 1903 | 1st Deakin | [34] |

| 3 | Chris Watson (1867–1941) |  | Labour | 27 April 1904 | 18 August 1904 | Bland, NSW, 1901–1906 South Sydney, NSW, 1906–1910 (retired) | — | Watson | [27] |

| 4 | George Reid (1845–1918) |  | Free Trade | 18 August 1904 | 5 July 1905 | East Sydney, NSW, 1901–1909 (resigned) | — | Reid | [35] |

(2) | Alfred Deakin (1856–1919) |  | Protectionist | 5 July 1905 | 13 November 1908 | Ballaarat, Vic,[Note 1] 1901–1913 (retired) | — | 2nd Deakin | |

1906 | 3rd Deakin | ||||||||

| 5 | Andrew Fisher (1862–1928) |  | Labour | 13 November 1908 | 2 June 1909 | Wide Bay, Qld, 1901–1915 (resigned) | — | 1st Fisher | [36] |

(2) | Alfred Deakin (1856–1919) |  | Commonwealth Liberal | 2 June 1909 | 29 April 1910 | Ballaarat, Vic,[Note 1] 1901–1913 (retired) | — | 4th Deakin | |

(5) | Andrew Fisher (1862–1928) |  | Labor | 29 April 1910 | 24 June 1913 | Wide Bay, Qld, 1901–1915 (resigned) | 1910 | 2nd Fisher | |

| 6 | Joseph Cook (1860–1947) |  | Commonwealth Liberal | 24 June 1913 | 17 September 1914 | Parramatta, NSW, 1901–1921 (resigned) | 1913 | Cook | [37] |

(5) | Andrew Fisher (1862–1928) |  | Labor | 17 September 1914 | 27 October 1915 | Wide Bay, Qld, 1901–1915 (resigned) | 1914 | 3rd Fisher | |

Billy Hughes (1862–1952) |  | Labor | 27 October 1915 | 14 November 1916 | West Sydney, NSW, 1901–1917 Bendigo, Vic, 1917–1922 North Sydney, NSW, 1922–1949 Bradfield, NSW, 1949–1952 (died) | — | 1st Hughes | [38] | |

| 7 | National Labor | 14 November 1916 | 17 February 1917 | — | 2nd Hughes | ||||

| Nationalist | 17 February 1917 | 9 February 1923 | — | 3rd Hughes | |||||

| 1917 | 4th Hughes | ||||||||

| 1919 | 5th Hughes | ||||||||

| 8 | Stanley Bruce (1883–1967) |  | Nationalist (Coalition) | 9 February 1923 | 22 October 1929 | Flinders, Vic, 1918–1929 (defeated) ; 1931–1933 (resigned) | 1922 | 1st Bruce | [28] |

1925 | 2nd Bruce | ||||||||

1928 | 3rd Bruce | ||||||||

| 9 | James Scullin (1876–1953) |  | Labor | 22 October 1929 | 6 January 1932 | Corangamite, Vic, 1910–1913 (defeated) Yarra, Vic, 1922–1949 (retired) | 1929 | Scullin | [39] |

| 10 | Joseph Lyons (1879–1939) |  | United Australia (Coalition) | 6 January 1932 | 7 April 1939† | Wilmot, Tas, 1929–1939 (died) | 1931 | 1st Lyons | [40] |

1934 | 2nd Lyons | ||||||||

| — | 3rd Lyons | ||||||||

1937 | 4th Lyons | ||||||||

| 11 | Sir Earle Page (1880–1961) |  | Country (Coalition) | 7 April 1939 | 26 April 1939 | Cowper, NSW 1919–1961 (defeated) | — | Page | [41] |

| 12 | Robert Menzies (1894–1978) |  | United Australia (Coalition) | 26 April 1939 | 28 August 1941 | Kooyong, Vic, 1934–1966 (resigned) | — | 1st Menzies | [29] |

2nd Menzies | |||||||||

1940 | 3rd Menzies | ||||||||

| 13 | Arthur Fadden (1894–1973) |  | Country (Coalition) | 28 August 1941 | 7 October 1941 | Darling Downs, Qld 1936–1949 McPherson, Qld 1949–1958 (retired) | — | Fadden | [32] |

| 14 | John Curtin (1885–1945) |  | Labor | 7 October 1941 | 5 July 1945† | Fremantle, WA, 1928–1931 (defeated) ; 1934–1945 (died) | — | 1st Curtin | |

1943 | 2nd Curtin | ||||||||

| 15 | Frank Forde (1890–1983) |  | Labor | 6 July 1945 | 13 July 1945 | Capricornia, Qld, 1922–1946 (defeated) | — | Forde | |

| 16 | Ben Chifley (1885–1951) |  | Labor | 13 July 1945 | 19 December 1949 | Macquarie, NSW, 1928–1931 (defeated) ; 1940–1951 (died) | — | 1st Chifley | |

1946 | 2nd Chifley | ||||||||

(12) | Sir Robert Menzies (1894–1978) |  | Liberal (Coalition) | 19 December 1949 | 26 January 1966 | Kooyong, Vic, 1934–1966 (resigned) | 1949 | 4th Menzies | |

1951 | 5th Menzies | ||||||||

1954 | 6th Menzies | ||||||||

1955 | 7th Menzies | ||||||||

1958 | 8th Menzies | ||||||||

1961 | 9th Menzies | ||||||||

1963 | 10th Menzies | ||||||||

| 17 | Harold Holt (1908–1967) |  | Liberal (Coalition) | 26 January 1966 | 19 December 1967† | Fawkner, Vic, 1935–1949 Higgins, Vic, 1949–1967 (disappeared) | — | 1st Holt | |

1966 | 2nd Holt | ||||||||

| 18 | John McEwen (1900–1980) |  | Country (Coalition) | 19 December 1967 | 10 January 1968 | Echuca, Vic, 1934–1937 Indi, Vic, 1937–1949 Murray, Vic, 1949–1971 (resigned) | — | McEwen | |

| 19 | John Gorton (1911–2002) |  | Liberal (Coalition) | 10 January 1968 | 10 March 1971 | Senator 1950–1968 (resigned)[Note 2] MP for Higgins, Vic, | — | 1st Gorton | |

1969 | 2nd Gorton | ||||||||

| 20 | William McMahon (1908–1988) |  | Liberal (Coalition) | 10 March 1971 | 5 December 1972 | Lowe, NSW, 1949–1982 (resigned) | — | McMahon | |

| 21 | Gough Whitlam (1916–2014) |  | Labor | 5 December 1972 | 11 November 1975 | Werriwa, NSW, 1952–1978 (resigned) | 1972 | 1st Whitlam | |

| — | 2nd Whitlam | ||||||||

1974 | 3rd Whitlam | ||||||||

| 22 | Malcolm Fraser (1930–2015) |  | Liberal (Coalition) | 11 November 1975 | 11 March 1983 | Wannon, Vic, 1955–1983 (resigned) | — | 1st Fraser | |

1975 | 2nd Fraser | ||||||||

1977 | 3rd Fraser | ||||||||

1980 | 4th Fraser | ||||||||

| 23 | Bob Hawke (1929–) |  | Labor | 11 March 1983 | 20 December 1991 | Wills, Vic, 1980–1992 (resigned) | 1983 | 1st Hawke | |

1984 | 2nd Hawke | ||||||||

1987 | 3rd Hawke | ||||||||

1990 | 4th Hawke | ||||||||

| 24 | Paul Keating (1944–) |  | Labor | 20 December 1991 | 11 March 1996 | Blaxland, NSW, 1969–1996 (resigned) | — | 1st Keating | |

1993 | 2nd Keating | ||||||||

| 25 | John Howard (1939–) |  | Liberal (Coalition) | 11 March 1996 | 3 December 2007 | Bennelong, NSW, 1974–2007 (defeated) | 1996 | 1st Howard | |

1998 | 2nd Howard | ||||||||

2001 | 3rd Howard | ||||||||

2004 | 4th Howard | ||||||||

| 26 | Kevin Rudd (1957–) |  | Labor | 3 December 2007 | 24 June 2010 | Griffith, Qld, 1998–2013 (resigned) | 2007 | 1st Rudd | |

| 27 | Julia Gillard (1961–) |  | Labor | 24 June 2010 | 27 June 2013 | Lalor, Vic, 1998–2013 (retired) | — | 1st Gillard | |

2010 | 2nd Gillard | ||||||||

(26) | Kevin Rudd (1957–) |  | Labor | 27 June 2013 | 18 September 2013 | Griffith, Qld, 1998–2013 (resigned) | — | 2nd Rudd | |

| 28 | Tony Abbott (1957–) |  | Liberal (Coalition) | 18 September 2013 | 15 September 2015 | Warringah, NSW, since 1994 | 2013 | Abbott | |

| 29 | Malcolm Turnbull (1954–) |  | Liberal (Coalition) | 15 September 2015 | 24 August 2018 | Wentworth, NSW, 2004–2018 (resigned) | — | 1st Turnbull | |

2016 | 2nd Turnbull | ||||||||

| 30 | Scott Morrison (1968–) |  | Liberal (Coalition) | 24 August 2018 | Incumbent | Cook, NSW, since 2007 | — | Morrison | |

See also

- Deputy Prime Minister of Australia

- List of Prime Ministers of Australia

- List of Prime Ministers of Australia by age

- List of Prime Ministers of Australia by time in office

- List of Prime Ministers of Australia (graphical)

- Historical rankings of Prime Ministers of Australia

Prime Ministers Avenue in Horse Chestnut Avenue in the Ballarat Botanical Gardens contains a collection of bronze busts of former Australian Prime Ministers.- Spouse of the Prime Minister of Australia

- Transportation of the Prime Minister of Australia

- List of Australian Leaders of the Opposition

- Prime Ministers of Queen Elizabeth II

- List of Commonwealth Heads of Government

- List of Privy Counsellors (1952–present)

- Prime Minister's XI

Notes

^ abc The Electoral Division of Ballaarat was spelled with a double a until 1977.

^ Gorton was elected to the Senate at the general election of 10 December 1949, but his term did not commence until 22 February 1950. He was appointed Prime Minister on 10 January 1968; resigned from the Senate on 1 February; and was elected to the House of Representatives at a by-election on 24 February.

^ Gorton retired from the House of Representatives at the double dissolution of 11 November 1975, and stood for an Australian Capital Territory Senate seat as an independent at the general election of 13 December 1975, but was unsuccessful.

References

^ "Heads of State, Government and Ministers for Foreign Affairs" (PDF). UN. United Nations Foreign and Protocol Service..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Australia's Constitution : With Overview and Notes by the Australian Government Solicitor (Pocket ed.). Canberra: Parliamentary Education Office and Australian Government Solicitor. 2010. p. v. ISBN 9781742293431.

^ "9 - Motions". House of Representatives Practice, 6th Ed – HTML version. Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

^ "Scott Morrison sworn in as Australia's 30th Prime Minister". ABC News. 15 September 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

^ "No. 14 - Ministers in the Senate". Senate Briefs. Parliament of Australia. December 2016.

^ "ParlInfo – Part 6 – Historical information on the Australian Parliament : Ministries and Cabinets". aph.gov.au.

^ Kerr, John. "Statement from John Kerr (dated 11 November 1975) explaining his decisions". WhitlamDismissal.com. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

^ "Administrative Arrangements Order" (PDF). Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Commonwealth of Australia. 1 September 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

^ https://www.coag.gov.au/about-coag

^ "Prime Minister Kevin Rudd and MPs in line to get a 3% pay rise".

^ Hudson, Phillip (25 August 2010). "Politicians awarded secret pay rise". Herald Sun. Australia.

^ [1] Archived 13 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Tony Abbott defends increase in MP salary, saying he's working hard for every Australian". Herald Sun. 5 July 2012.

^ Peatling, Stephanie (14 June 2013). "PM's salary tops $500,000". Sydney Morning Herald.

^ Mannheim, Markus (10 December 2015). "Politicians, judges and top public servants to gain 2% pay rise after wage freeze". Canberra Times.

^ ab "Politicians under fire for pay increases while penalty rates cut, One Nation wants to reject rise". 23 June 2017.

^ Bagshaw, Eryk (26 May 2018). "At $528,000 a year, Turnbull's pay is highest of any leader in OECD". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

^ Canberra Times, 18 August 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2018

^ Metherell, Mark (19 February 2008). "Rudds' staff extends to a child carer at the Lodge". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

^ CarAdvice.com.au (6 April 2009). "25% of government car fleet foreign made". Car Advice. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

^ Hutchens, Gareth (7 February 2017). "Malcolm Turnbull to scrap Life Gold Pass for former MPs". the Guardian.

^ "Australian Dictionary of Biography – William Alexander Watt". ADB ANU. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

^ "Australian Dictionary of Biography – Sir George Foster Pearce". ADB ANU. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

^ Cox, Lisa. "The 'special moment' seven surviving Prime Ministers were photographed together".

^ "After office". naa.gov.au.

^ "Prime Minister of Australia". Australian Policy Online. Archived from the original on 17 September 2015.

^ ab Nairn, Bede (1990). "Watson, John Christian (1867–1941)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

^ ab Radi, Heather (1979). "Bruce, Stanley Melbourne [Viscount Bruce] (1883–1967)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

^ ab Martin, A. W. "Menzies, Sir Robert Gordon (Bob) (1894–1978)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

^ "McEwen, Sir John (1900–1980)". Australian Dictionary of Biography.

^ "McMahon, Sir William (Billy) (1908–1988)". Australian Dictionary of Biography.

^ ab Cribb, Margaret Bridson. "Fadden, Sir Arthur William (1894–1973)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

^ Rutledge, Martha. "Barton, Sir Edmund (1849–1920)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian National University. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

^ Norris, R. (1981). "Deakin, Alfred (1856–1919)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

^ McMinn, W. G. "Reid, Sir George Houstoun (1845–1918)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian National University. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

^ Murphy, D. J. "Fisher, Andrew (1862–1928)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian National University. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

^ Crowley, F. K. "Cook, Sir Joseph (1860–1947)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian National University. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

^ Fitzhardinge, L. F. "Hughes, William Morris (Billy) (1862–1952)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian National University. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

^ Robertson, J. R. (1988). "Scullin, James Henry (1876–1953)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

^ Hart, P. R. (1986). "Lyons, Joseph Aloysius (1879–1939)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

^ Bridge, Carl. "Page, Sir Earle Christmas Grafton (1880–1961)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

Further reading

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Strangio, Paul; t'Hart, Paul & Walter, James (2016). Settling the Office: The Australian Prime Ministership from Federation to Reconstruction. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 9780522868722.

Strangio, Paul; t'Hart, Paul & Walter, James (2017). The Pivot of Power: Australian Prime Ministers and Political Leadership, 1949-2016. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 9780522868746.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prime Ministers of Australia. |

Library resources about Prime Minister of Australia |

|

- Official website of the Prime Minister of Australia

- Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet

Australia's Prime Ministers – National Archives of Australia reference site and research portal

Biographies of Australia's Prime Ministers / National Museum of Australia- Classroom resources on Australian Prime Ministers