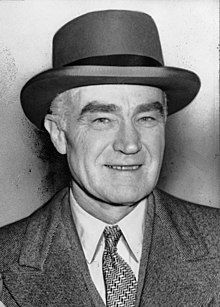

Henry Luce

Henry Luce | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Henry Robinson Luce (1898-04-03)April 3, 1898 Tengchow, China |

| Died | February 28, 1967(1967-02-28) (aged 68) Phoenix, Arizona, U.S. |

| Occupation | Publisher; Journalist |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Lila Ross Hotz (m. 1923; div. 1935) Clare Boothe Luce (m. 1935) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent(s) | Henry W. Luce Elizabeth Middleton Root |

Henry Robinson Luce (April 3, 1898 – February 28, 1967) was an American magazine magnate who was called "the most influential private citizen in the America of his day".[1] He launched and closely supervised a stable of magazines that transformed journalism and the reading habits of millions of Americans. Time summarized and interpreted the week's news; Life was a picture magazine of politics, culture, and society that dominated American visual perceptions in the era before television; Fortune reported on national and international business; and Sports Illustrated explored the world of sports. Counting his radio projects and newsreels, Luce created the first multimedia corporation. He envisaged that the United States would achieve world hegemony, and, in 1941, he declared the 20th century would be the "American Century".[2][3]

Contents

1 Early life

2 Career

3 Magazines

4 Family

5 References

6 Further reading

7 External links

Early life

Luce was born in Tengchow (now Penglai), Shandong, China, on April 3, 1898, the son of Elizabeth Root Luce and Henry Winters Luce, who was a Presbyterian missionary.[3] He received his education in various Chinese and English boarding schools, including the China Inland Mission Chefoo School.

Career

At 15, he was sent to the US to attend the Hotchkiss School in Connecticut, where he edited the Hotchkiss Literary Monthly. There, he first met Briton Hadden,[3] who would become a lifelong partner. At the time, Hadden served as editor-in-chief of the school newspaper, and Luce worked as an assistant managing editor. Both went on to Yale College, where Hadden served as chairman and Luce as managing editor of The Yale Daily News. Luce was also a member of Alpha Delta Phi and Skull and Bones. After being voted "most brilliant" of his class and graduating in 1920, he parted ways with Hadden to embark for a year on historical studies at Oxford University, followed by a stint as a cub reporter for the Chicago Daily News.

In December 1921, Luce rejoined Hadden to work at The Baltimore News. Recalling his relationship with Hadden, Luce later said, "Somehow, despite the greatest differences in temperaments and even in interests, we had to work together. We were an organization. At the center of our lives — our job, our function — at that point everything we had belonged to each other."[citation needed]

Magazines

Nightly discussions of the concept of a news magazine led Luce and Hadden, both age 23, to quit their jobs in 1922. Later that same year, they partnered with Robert Livingston Johnson and another Yale classmate to form Time Inc.[4] Having raised $86,000 of a $100,000 goal, they published the first issue of Time on March 3, 1923. Luce served as business manager while Hadden was editor-in-chief. Luce and Hadden annually alternated year-to-year the titles of president and secretary-treasurer while Johnson served as vice president and advertising director. In 1925, Luce decided to move headquarters to Cleveland, while Hadden was on a trip to Europe. Cleveland was cheaper, and Luce’s first wife, Lila, wanted out of New York. When Hadden returned, he was horrified and moved Time back to New York. Upon Hadden's sudden death in 1929, Luce assumed Hadden's position.

Luce launched the business magazine Fortune in February 1930 and acquired Life in order to relaunch it as a weekly magazine of photojournalism in November 1936; he went on to launch House & Home in 1952 and Sports Illustrated in 1954. He also produced The March of Time weekly newsreel. By the mid 1960s, Time Inc. was the largest and most prestigious magazine publisher in the world. (Dwight Macdonald, a Fortune staffer during the 1930s, referred to him as "Il Luce", a play on the Italian Dictator Mussolini, who was called "Il Duce".)

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, aware that most publishers were opposed to him, issued a decree in 1943 that blocked all publishers and media executives from visits to combat areas; he put General George Marshall in charge of enforcement.[citation needed] The main target was Luce, who had long opposed Roosevelt. Historian Alan Brinkley argued the move was "badly mistaken" and said had Luce been allowed to travel, he would have been an enthusiastic cheerleader for American forces around the globe.[citation needed] However, stranded in New York City, Luce's frustration and anger expressed itself in blatant partisanship.[5]

Luce, supported by Editor-in-Chief T. S. Matthews, appointed Whittaker Chambers as acting Foreign News editor in 1944, despite the feuds that Chambers had with reporters in the field.[6]

Luce, who remained editor-in-chief of all his publications until 1964, maintained a position as an influential member of the Republican Party.[7] An instrumental figure behind the so-called "China Lobby", he played a large role in steering American foreign policy and popular sentiment in favor of Kuomintang leader Chiang Kai-shek and his wife, Soong Mei-ling, in their war against the Japanese. (The Chiangs appeared in the cover of Time eleven times between 1927 and 1955.[8])

It has been reported that Luce, during the 1960s, tried LSD and reported that he had talked to God under its influence.[9]

Once ambitious to become Secretary of State in a Republican administration, Luce penned a famous article in Life magazine in 1941, called "The American Century", which defined the role of American foreign policy for the remainder of the 20th century (and perhaps beyond).[7]

An ardent anti-Soviet, he once demanded John Kennedy invade Cuba, later to remark to his editors that if he did not, his corporation would act like Hearst during the Spanish–American War. The publisher would advance his concepts of US dominance of the "American Century" through his periodicals with the ideals shared and guided by members of his social circle, John Foster Dulles, Secretary of State and his brother, director of the CIA, Allen Dulles.[citation needed]

Family

Luce Memorial Chapel, Tunghai University, Taiwan.

Luce met his first wife, Lila Hotz, while he was studying at Yale in 1919.[10] They married in 1923 and had two children, Peter Paul and Henry Luce III, before divorcing in 1935.[10] In 1935 he married his second wife, Clare Boothe Luce, who had an 11-year-old daughter, Ann Clare Brokaw, whom he raised as his own. He died in Phoenix, Arizona in 1967. At his death, he was said to be worth $100 million in Time Inc. stock.[11] Most of his fortune went to the Henry Luce Foundation, where his son Henry III served as chairman and chief executive for many years.[10] During his life, Luce supported many philanthropies such as Save the Children Federation, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and United Service to China, Inc. He is interred at Mepkin Plantation in South Carolina.

He was honored by the United States Postal Service with a 32¢ Great Americans series (1980–2000) postage stamp.[12] Luce was inducted into the Junior Achievement U.S. Business Hall of Fame in 1977.[citation needed]

Designed by I. M. Pei, the Luce Memorial Chapel, on the campus of Tunghai University, Taiwan, was constructed in memoriam of Henry Luce's father.

References

^ Robert Edwin Herzstein (2005). Henry R. Luce, Time, and the American Crusade in Asia. Cambridge U.P. p. 1..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Editorial (1941-02-17) The American Century, Life Magazine

^ abc Baughman, James L. (April 28, 2004). "Henry R. Luce and the Rise of the American News Media". American Masters (PBS). Retrieved 19 June 2014.

^ Warburton, Albert (Winter 1962). "Robert L. Johnson Hall Dedicated at Temple University" (PDF). The Emerald of Sigma Pi. Vol. 48 no. 4. p. 111.

^ Alan Brinkley, The Publisher: Henry Luce and his American Century (2010) pp. 302–03

^ Brinkley, The Publisher: Henry Luce and his American Century (2010) pp. 322–93

^ ab "Henry R. Luce: End of a Pilgrimage". Time. March 10, 1967

^ "Time magazine historical search". Time magazine. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

^ Maisto, Stephen A., Galizio, Mark, & Connors, Gerald J. (2008). Drug Use and Abuse: Fifth Edition. Belmont: Thomson Higher Education.

ISBN 0-495-09207-X

^ abc Ravo, Nick (April 3, 1999). "Lila Luce Tyng, 100, First Wife of Henry R. Luce". The New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

^ Edwin Diamond (October 23, 1972). "Why the Power Vacuum at Time Inc. Continues". New York Magazine.

^ "Henry R. Luce". US Stamp Gallery. April 3, 1998.

Further reading

Baughman, James L. "Henry R. Luce and the Business of Journalism." Business & Economic History On-Line 9 (2011). online

Baughman, James L. Henry R. Luce and the Rise of the American News Media (2001) excerpt and text search

- Brinkley, Alan. The Publisher: Henry Luce and His American Century, Alfred A. Knopf (2010) 531 pp.

"A Magazine Master Builder" Book review by Janet Maslin, The New York Times, April 19, 2010

- Brinkley, Alan. What Would Henry Luce Make of the Digital Age?, Time (April 19, 2010) excerpt and text search

- Elson, Robert T. Time Inc: The Intimate History of a Publishing Enterprise, 1923–1941 (1968); vol. 2: The World of Time Inc.: The Intimate History, 1941–1960 (1973), official corporate history

- Herzstein, Robert E. Henry R. Luce, Time, and the American Crusade in Asia (2006) excerpt and text search

- Herzstein, Robert E. Henry R. Luce: A Political Portrait of the Man Who Created the American Century (1994).

Morris, Sylvia Jukes. Rage for Fame: The Ascent of Clare Boothe Luce (1997).- Wilner, Isaiah. The Man Time Forgot: A Tale of Genius, Betrayal, and the Creation of Time Magazine, HarperCollins, New York, 2006

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Luce. |

- TIME biography

- The Henry Luce Foundation

- Luce Center for American Art at the Brooklyn Museum – Visible Storage and Study Center

- Whitman, Alden. "Henry R. Luce, Creator of Time–Life Magazine Empire, Dies in Phoenix at 68", The New York Times, March 1, 1967.

- PBS American Masters

Henry Luce at Find a Grave

- Henry Luce at NNDB

Henry R. Luce Papers at the New-York Historical Society