Modern architecture

Top: Villa Savoye by Le Corbusier (1927); TWA Flight Center at JFK Airport by Eero Saarinen (1962): Center: Skyline of Chicago: Bottom: Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright (1935); Sydney Opera House by Jørn Utzon (1973) | |

| Years active | 1888–2000 |

|---|---|

| Country | International |

Modern architecture, or modernist architecture was based upon new and innovative technologies of construction, particularly the use of glass, steel and reinforced concrete; the idea that form should follow function; an embrace of minimalism; and a rejection of ornament.[1]

It emerged in the first half of the 20th century and became dominant after World War II until the 1980s, when it was gradually replaced as the

principal style for institutional and corporate buildings by Postmodern architecture.[2]

Contents

1 Origins

2 Early modernism in Europe (1900–1914)

3 Early American modernism (1900–1914)

3.1 Early skyscrapers

4 Rise of Modernism in Europe and Russia (1918–1931)

4.1 International Style (1918–1950s)

4.2 Bauhaus and the German Werkbund (1919–1932)

4.3 Expressionist architecture (1918–1931)

4.4 Constructivist architecture (1919–1931)

4.5 Modernism becomes a movement: CIAM (1928)

5 Art Deco

5.1 American Art Deco; the skyscraper style (1919–1939)

5.2 Streamline style and Public Works Administration (1933–1939)

6 American modernism - Frank Lloyd Wright, Rudolph Schindler, Richard Neutra (1919–1939)

7 Paris International Exposition of 1937 and the architecture of dictators

8 New York World's Fair (1939)

9 World War II: wartime innovation and postwar reconstruction (1939–1945)

10 Le Corbusier and the Cité Radieuse (1947–1952)

11 Postwar modernism in the United States (1945–1985)

11.1 Frank Lloyd Wright and the Guggenheim Museum

11.2 Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer

11.3 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

11.4 Richard Neutra and Charles & Ray Eames

11.5 Skidmore, Owings and Merrill and Wallace K. Harrison

11.6 Philip Johnson

11.7 Eero Saarinen

11.8 Louis Kahn

11.9 I. M. Pei

12 Postwar modernism in Europe (1945–1975)

13 Latin America

14 Asia and the Pacific

15 Preservation

16 See also

17 References

17.1 Notes and citations

17.2 Bibliography

18 External links

Origins

The Crystal Palace, 1851, was one of the first buildings to have cast plate glass windows supported by a cast-iron frame

The first house built of reinforced concrete, designed by François Coignet (1853) in Saint-Denis near Paris

The Home Insurance Building in Chicago, by William Le Baron Jenney, (1884)

The Eiffel Tower being constructed (August 1887-89)

Modern architecture emerged at the end of the 19th century from revolutions in technology, engineering and building materials, and from a desire to break away from historical architectural styles and to invent something that was purely functional and new.

The revolution in materials came first, with the use of cast iron, plate glass, and reinforced concrete, to build structures that were stronger, lighter and taller. The cast plate glass process was invented in 1848, allowing the manufacture of very large windows. The Crystal Palace by Joseph Paxton at the Great Exhibition of 1851 was an early example of iron and plate glass construction, followed in 1864 by the first glass and metal curtain wall. These developments together led to the first steel-framed skyscraper, the ten-story Home Insurance Building in Chicago, built in 1884 by William Le Baron Jenney.[3] The iron frame construction of the Eiffel Tower, then the tallest structure in the world, captured the imagination of millions of visitors to the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition.[4]

French industrialist François Coignet was the first to use iron-reinforced concrete, that is, concrete strengthened with iron bars, as a technique for constructing buildings.[5] In 1853 Coignet built the first iron reinforced concrete structure, a four-story house in the suburbs of Paris.[5] A further important step forward was the invention of the safety elevator by Elisha Otis, first demonstrated at the Crystal Palace exposition in 1852, which made tall office and apartment buildings practical.[6] Another important technology for the new architecture was electric light, which greatly reduced the inherent danger of fires caused by gas in the 19th century.[7]

The debut of new materials and techniques inspired architects to break away from the neoclassical and eclectic models that dominated European and American architecture in the late 19th century, most notably eclecticism, Victorian and Edwardian architecture, and the Beaux-Arts architectural style.[8] This break with the past was particularly urged by the architectural theorist and historian Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. In his 1872 book Entretiens sur L'Architecture, he urged: "use the means and knowledge given to us by our times, without the intervening traditions which are no longer viable today, and in that way we can inaugurate a new architecture. For each function its material; for each material its form and its ornament."[9] This book influenced a generation of architects, including Louis Sullivan, Victor Horta, Hector Guimard, and Antoni Gaudí.[10]

Early modernism in Europe (1900–1914)

The Glasgow School of Art by Charles Rennie MacIntosh (1896–99)

Reinforced concrete apartment building by Auguste Perret, Paris (1903)

Austrian Postal Savings Bank in Vienna by Otto Wagner (1904–1906)

The AEG Turbine factory by Peter Behrens (1909)

The Steiner House in Vienna by Adolf Loos (1910)

Stoclet Palace by Josef Hoffmann, Brussels, (1906–1911)

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris by Auguste Perret (1911–1913)

Stepped concrete apartment building in Paris by Henri Sauvage (1912–1914)

The Fagus Factory in Alfeld by Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer (1911–13)

The Glass Pavilion in Cologne by German architect Bruno Taut (1914)

At the end of the 19th century, a few architects began to challenge the traditional Beaux Arts and Neoclassical styles that dominated architecture in Europe and the United States. The Glasgow School of Art (1896-99) designed by Charles Rennie MacIntosh, had a facade dominated by large vertical bays of windows.[11] The Art Nouveau style was launched in the 1890s by Victor Horta in Belgium and Hector Guimard in France; it introduced new styles of decoration, based on vegetal and floral forms. In Barcelona, Antonio Gaudi conceived architecture as a form of sculpture; the facade of the Casa Battlo in Barcelona (1904–1907) had no straight lines; it was encrusted with colorful mosaics of stone and ceramic tiles [12]

Architects also began to experiment with new materials and techniques, which gave them greater freedom to create new forms. In 1903–1904 in Paris Auguste Perret and Henri Sauvage began to use reinforced concrete, previously only used for industrial structures, to build apartment buildings.[13] Reinforced concrete, which could be molded into any shape, and which could create enormous spaces without the need of supporting pillars, replaced stone and brick as the primary material for modernist architects. The first concrete apartment buildings by Perret and Sauvage were covered with ceramic tiles, but in 1905 Perret built the first concrete parking garage on 51 rue de Ponthieu in Paris; here the concrete was left bare, and the space between the concrete was filled with glass windows. Henri Sauvage added another construction innovation in an apartment building on Rue Vavin in Paris (1912–1914); the reinforced concrete building was in steps, with each floor set back from the floor below, creating a series of terraces. Between 1910 and 1913, Auguste Perret built the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, a masterpiece of reinforced concrete construction, with Art Deco sculptural bas-reliefs on the facade by Antoine Bourdelle. Because of the concrete construction, no columns blocked the spectator's view of the stage.[14]

Otto Wagner, in Vienna, was another pioneer of the new style. In his book Moderne Architektur (1895) he had called for a more rationalist style of architecture, based on "modern life".[15] He designed a stylized ornamental metro station at Karlsplatz in Vienna (1888–89), then an ornamental Art Nouveau residence, Majolika House (1898), before moving to a much more geometric and simplified style, without ornament, in the Austrian Postal Savings Bank (1904–1906). Wagner declared his intention to express the function of the building in its exterior. The reinforced concrete exterior was covered with plaques of marble attached with bolts of polished aluminum. The interior was purely functional and spare, a large open space of steel, glass and concrete where the only decoration was the structure itself.[16]

The Viennese architect Adolf Loos also began removing any ornament from his buildings. His Steiner House, in Vienna (1910), was an example of what he called rationalist architecture; it had a simple stucco rectangular facade with square windows and no ornament. . The fame of the new movement, which became known as the Vienna Secession spread beyond Austria. Josef Hoffmann, a student of Wagner, constructed a landmark of early modernist architecture, the Palais Stoclet, in Brussels, in 1906–1911. This residence, built of brick covered with Norwegian marble, was composed of geometric blocks, wings and a tower. A large pool in front of the house reflected its cubic forms. The interior was decorated with paintings by Gustav Klimt and other artists, and the architect even designed clothing for the family to match the architecture.[17]

In Germany, a modernist industrial movement, Deutscher Werkbund (German Work Federation) had been created in Munich in 1907 by Hermann Muthesius, a prominent architectural commentator. Its goal was to bring together designers and industrialists, to turn out well-designed, high quality products, and in the process to invent a new type of architecture.[18] The organization originally included twelve architects and twelve business firms, but quickly expanded. The architects include Peter Behrens, Theodor Fischer (who served as its first president), Josef Hoffmann and Richard Riemerschmid.[19] In 1909 Behrens designed one of the earliest and most influential industrial buildings in the modernist style, the AEG turbine factory, a functional monument of steel and concrete. In 1911–1913, Adolf Meyer and Walter Gropius, who had both worked for Behrens, built another revolutionary industrial plant, the Fagus factory in Alfeld an der Leine, a building without ornament where every construction element was on display. The Werkbund organized a major exposition of modernist design in Cologne just a few weeks before the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. For the 1914 Cologne exhibition, Bruno Taut built a revolutionary glass pavilion.[20]

Early American modernism (1900–1914)

William H. Winslow House, by Frank Lloyd Wright, Oak Park, Illinois (1893-94)

The Arthur Heurtley House in Oak Park, Illinois (1902)

Larkin Administration Building by Frank Lloyd Wright, Buffalo, New York (1904–1906)

Interior of Unity Temple by Frank Lloyd Wright, Oak Park, Illinois (1905–1908)

The Robie House by Frank Lloyd Wright, Chicago (1909)

Frank Lloyd Wright was a highly original and independent American architect who refused to be categorized in any one architectural movement. Like Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, he had no formal architectural training. In 1887-93 he worked in the Chicago office of Louis Sullivan, who pioneered the first tall steel-frame office buildings in Chicago, and who famously stated "form follows function." [21] Wright set out to break all the traditional rules. Wright was particularly famous for his Prairie Houses, including the Winslow House in River Forest, Illinois(1893–94),;Arthur Heurtley House (1902) and Robie House (1909); sprawling, geometric residences without decoration, with strong horizontal lines which seemed to grow out of the earth, and which echoed the wide flat spaces of the American prairie. His Larkin Building (1904–1906) in Buffalo, New York, Unity Temple (1905) in Oak Park, Illinois and Unity Temple had highly original forms and no connection with historical precedents. [22]

Early skyscrapers

Home Insurance Building in Chicago by William Le Baron Jenney (1883)

Prudential (Guaranty) Building by Louis Sullivan in Buffalo, New York (1896)

The Flatiron Building in New York City (1903)

The Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building in Chicago by Louis Sullivan (1904–1906)

The Woolworth Building and the New York skyline in 1913. It was modern on the inside but neo-Gothic on the outside.

The neo-Gothic crown of the Woolworth Building by Cass Gilbert (1912)

At the end of the 19th century, the first skyscrapers began to appear in the United States. They were a response to the shortage of land and high cost of real estate in the center of the fast-growing American cities, and the availability of new technologies, including fireproof steel frames and improvements in the safety elevator invented by Elisha Otis in 1852. The first steel-framed "skyscraper", The Home Insurance Building in Chicago, was ten stories high. It was designed by William Le Baron Jenney in 1883, and was briefly the tallest building in the world. Louis Sullivan built another monumental new structure, the Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building, in the heart of Chicago in 1904-06. While these buildings were revolutionary in their steel frames and height, their decoration was borrowed from neo-renaissance, Neo-Gothic and Beaux-Arts architecture. The Woolworth Building, designed by Cass Gilbert, was completed in 1912, and was the tallest building in the world until the completion of the Chrysler Building in 1929. The structure was purely modern, but its exterior was decorated with Neo-Gothic ornament, complete with decorative buttresses, arches and spires, which caused it be nicknamed the "Cathedral of Commerce." [23]

Rise of Modernism in Europe and Russia (1918–1931)

After the first World War, a prolonged struggle began between architects who favored the more traditional styles of neo-classicism and the Beaux-Arts architecture style, and the modernists, led by Le Corbusier and Robert Mallet-Stevens in France, Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in Germany, and Konstantin Melnikov in the new Soviet Union, who wanted only pure forms and the elimination of any decoration. Art Deco architects such as Auguste Perret and Henri Sauvage often made a compromise between the two, combining modernist forms and stylized decoration.

International Style (1918–1950s)

The Villa La Roche-Jeanneret (now Fondation Le Corbusier) by Le Corbusier, Paris (1923–25)

Corbusier Haus in Weissenhof Estate, Stuttgart, Germany (1927)

Citrohan Haus in Weissenhof Estate, Stuttgart, Germany by Le Corbusier (1927)

The Villa Savoye in Poissy by Le Corbusier (1928–31)

Villa Paul Poiret by Robert Mallet-Stevens (1921–1925)

The Villa Noailles in Hyères by Robert Mallet-Stevens (1923)

Hôtel Martel rue Mallet-Stevens, by Robert Mallet-Stevens (1926–1927)

The dominant figure in the rise of modernism in France was Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, a Swiss-French architect who in 1920 took the name Le Corbusier. In 1920 he co-founded a journal called 'L'Espirit Nouveau and energetically promoted architecture that was functional, pure, and free of any decoration or historical associations. He was also a passionate advocate of a new urbanism, based on planned cities. In 1922 he presented a design of a city for three million people, whose inhabitants lived in identical sixty-story tall skyscrapers surrounded by open parkland. He designed modular houses, which would be mass-produced on the same plan and assembled into apartment blocks, neighborhoods and cities. In 1923 he published "Toward an Architecture", with his famous slogan, "a house is a machine for living in."[24] He tirelessly promoted his ideas through slogans, articles, books, conferences, and participation in Expositions.

To illustrate his ideas, in the 1920s he built a series of houses and villas in and around Paris. They were all built according to a common system, based upon the use of reinforced concrete, and of reinforced concrete pylons in the interior which supported the structure, allowing glass curtain walls on the facade and open floor plans, independent of the structure. They were always white, and had no ornament or decoration on the outside or inside. The best-known of these houses was the Villa Savoye, built in 1928–1931 in the Paris suburb of Poissy. An elegant white box wrapped with a ribbon of glass windows around on the facade, with living space that opened upon an interior garden and countryside around, raised up by a row of white pylons in the center of a large lawn, it became an icon of modernist architecture.[25]

Bauhaus and the German Werkbund (1919–1932)

The Bauhaus school building at Dessau, Germany, designed by Walter Gropius (1926)

A Bauhaus design for a worker's apartment, by Walter Gropius (1928-30)

The Barcelona Pavilion (modern reconstruction) by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1929)

The Weissenhof Estate in Stuttgart, initiated and realized by the German Werkbund (1927)

In Germany, two important modernist movements appeared after the first World War, The Bauhaus was a school organized Weimar in 1919 under the direction of Walter Gropius. Gropius was the son of the official state architect of Berlin, who studied before the war with Peter Behrens, and designed the modernist Fagus turbine factory. The Bauhaus was a fusion of the prewar Academy of Arts and the school of technology. In 1926 it was transferred from Weimar to Dessau; Gropius designed the new school and student dormitories in the new, purely functional modernist style he was encouraging. The school brought together modernists in all fields; the faculty included the modernist painters Vasily Kandinsky, Joseph Albers and Paul Klee, and the designer Marcel Breuer.

Gropius became an important theorist of modernism, writing ‘’The Idea and Construction’’ in 1923. He was an advocate of standardization in architecture, and the mass construction of rationally-designed apartment blocks for factory workers. In 1928 he was commissioned by the Siemens company to build apartment for workers in the suburbs of Berlin, and in 1929 he proposed the construction of clusters of slender eight to ten story high rise apartment towers for workers.

While Gropius was active at the Bauhaus, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe led the modernist architectural movement in Berlin. Inspired by the De Stijl movement in the Netherlands, he built clusters of concrete summer houses and proposed a project for a glass office tower. He became the vice president of the German ‘’Werkbund’’, and became the head of the Bauhaus from 1930 to 1932. proposing a wide variety of modernist plans for urban reconstruction. His most famous modernist work was the German pavilion for the 1929 international exposition in Barcelona. It was a work of pure modernism, with glass and concrete walls and clean, horizontal lines. Though it was only a temporary structure, and was torn down in 1930, it became, along with Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye, one of best-known landmarks of modernist architecture. A reconstructed version now stands on the original site in Barcelona.[26]

When the Nazis came to power in Germany, they viewed the Bauhaus as a training ground for communists, and closed the school in 1932. Gropius left Germany and went to England, then to the United States, where he and Marcel Breuer both joined the faculty of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and became the teachers of a generation of American postwar architects. In 1937 Mies van der Rohe also moved to the United States; he became one of the most famous designers of postwar American skyscrapers.[26]

Expressionist architecture (1918–1931)

Foyer of the Großes Schauspielhaus, or Great Theater, in Berlin by Hans Poelzig (1919)

The Einstein Tower by Erich Mendelsohn (1920–24)

The Mossehaus in Berlin by Erich Mendelsohn, an early example of streamline moderne (1921–23)

The Chilehaus in Hamburg by Fritz Höger (1921–24)

Horseshoe-shaped public housing project by Bruno Taut (1925)

Second Goetheanum in Dornach near Basel (Switzerland) by the Austrian architect Rudolf Steiner (1924–1928)

Het Schip apartment building in Amsterdam by Michel de Klerk (1917–1920)

De Bijenkorf store in The Hague by Piet Kramer (1924–1926)

Expressionism, which appeared in Germany between 1910 and 1925, was a counter-movement against the strictly functional architecture of the Bauhaus and Werkbund. Its advocates, including Bruno Taut, Hans Poelzig, Fritz Hoger and Erich Mendelsohn, wanted to create architecture that was poetic, expressive, and optimistic. Many expressionist architects had fought in World War I and their experiences, combined with the political turmoil and social upheaval that followed the German Revolution of 1919, resulted in a utopian outlook and a romantic socialist agenda.[27] Economic conditions severely limited the number of built commissions between 1914 and the mid–1920s,[28] As result, many of the most innovative expressionist projects, including Bruno Taut's Alpine Architecture and Hermann Finsterlin's Formspiels, remained on paper. Scenography for theatre and films provided another outlet for the expressionist imagination,[29] and provided supplemental incomes for designers attempting to challenge conventions in a harsh economic climate. A particular type, using bricks to create its forms (rather than concrete) is known as Brick Expressionism.

Erich Mendelsohn, (who disliked the term Expressionism for his work) began his career designing churches, silos, and factories which were highly imaginative, but, for lack of resources, were never built In 1920, he finally was able to construct one of his works in the city of Potsdam; an observatory and research center called the Einsteinium, named in tribute to Albert Einstein. It was supposed to be built of reinforced concrete, but because of technical problems it was finally built of traditional materials covered with plaster. His sculptural form, very different from the austere rectangular forms of the Bauhaus, first won him commissions to build movie theaters and retail stores in Stuttgart, Nuremberg and Berlin. His Mossehaus in Berlin was an early model for the streamline moderne style. His Columbushaus on Potsdamer Platz in Berlin (1931) was a prototype for the modernist office buildings that followed. (It was torn down in 1957, because it stood in the zone between East and West Berlin, where the Berlin Wall was constructed.) Following the rise of the Nazis to power, he moved to England (1933), then to the United States (1941).[30]

Fritz Höger was another notable Expressionist architect of the period. His Chilehaus was built as the headquarters of a shipping company, and was modeled after a giant steamship, a triangual building with a sharply pointed bow. It was constructed of dark brick, and used external piers to express its vertical structure. Its external decoration borrowed from Gothic cathedrals, as did its internal arcades. Hans Poelzig was another notable expressionist architect. In 1919 he built the Großes Schauspielhaus, an immense theater in Berlin, seating five thousand spectators for theater impresario Max Reinhardt. It featured elongated shapes like stalagmites hanging down from its gigantic dome, and lights on massive columns in its foyer. He also constructed the IG Farben building, a massive corporate headquarters, now the main building of Goethe University in Frankfurt. Bruno Taut specialized in building large scale apartment complexes for working-class Berliners. He built twelve thousand individual units, sometimes in buildings with unusual shapes, such as a giant horseshoe. Unlike most other modernists, he used bright exterior colors to give his buildings more life The use of dark brick in the German projects gave that particular style a name, Brick Expressionism.[31]

The Austrian philosopher, architect and social critic Rudolf Steiner also departed as far as possible from traditional architectural forms. His Second Goetheanum, built from 1926 near Basel, Switzerland the Einsteinturm in Potsdam, Germany, and the Second Goetheanum, by Rudolf Steiner (1926), were based on no traditional models, and had entirely original shapes.

Constructivist architecture (1919–1931)

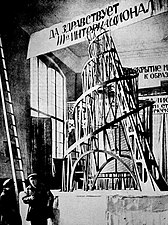

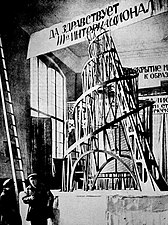

Model of the Tower for the Third International, by Vladimir Tatlin (1919)

the Lenin Mausoleum in Moscow by Alexey Shchusev (1924)

The USSR Pavilion at the 1925 Paris Exposition of Decorative Arts, by Konstantin Melnikov (1925)

Rusakov Workers' Club, Moscow, by Konstantin Melnikov (1928)

Derzhprom (the House of Industry), Kharkiv, by Sergey Serafimovich, Samul Kravets and Marc Felger (1928)

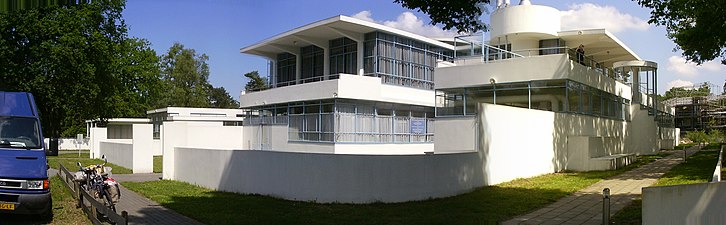

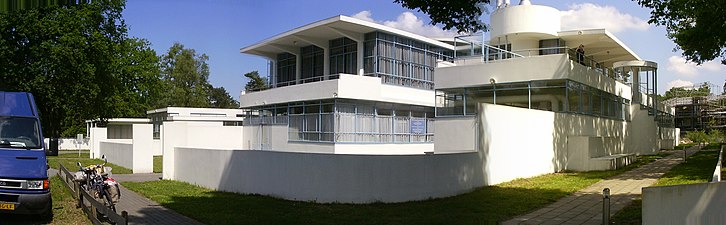

Zonnestraal Sanatorium in Hilversum by Jan Duiker and Bernard Bijvoet (1926–1928)

Open air school in Amsterdam by Jan Duiker (1929–1930)

Van Nelle Factory in Rotterdam by Leendert van der Vlugt and Mart Stam (1927–1931)

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Russian avant-garde artists and architects began searching for a new Soviet style which could replace traditional neoclassicism. The new architectural movements were closely tied with the literary and artistic movements of the period, the futurism of poet Vladimir Mayakovskiy, the Suprematism of painter Kasimir Malevich, and the colorful Rayonism of painter Mikhail Larionov. The most startling design that emerged was the tower proposed by painter and sculptor Vladimir Tatlin for the Moscow meeting of the Third Communist International in 1920: he proposed two interlaced towers of metal four hundred meters high, with four geometric volumes suspended from cables. The movement of Russian Constructivist architecture was launched in 1921 by a group of artists led by Aleksandr Rodchenko. Their manifesto proclaimed that their goal was to find the "communist expression of material structures." Soviet architects began to construct workers' clubs, communal apartment houses, and communal kitchens for feeding whole neighborhoods.[32]

One of the first prominent constructivist architects to emerge in Moscow was Konstantin Melnikov, the number of working clubs - including Rusakov Workers' Club (1928) - and his own living house, Melnikov House (1929) near Arbat Street in Moscow. Melnikov traveled to Paris in 1925 where he built the Soviet Pavilion for the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris in 1925; it was a highly geometric vertical construction of glass and steel crossed by a diagonal stairway, and crowned with a hammer and sickle. The leading group of constructivist architects, led by Vesnin brothers and Moisei Ginzburg, was publishing the 'Contemporary Architecture' journal. This group created several major constructivist projects in the wake of the First Five Year Plan - including colossal Dnieper Hydroelectric Station (1932) - and made an attempt to start the standardization of living blocks with Ginzburg's Narkomfin building. A number of architects from the pre-Soviet period also took up the constructivist style. The most famous example was Lenin's Mausoleum in Moscow (1924), by Alexey Shchusev (1924)[33]

The main centers of constructivist architecture were Moscow and Leningrad; however, during the industrialization lots of constructivist buildings were erected in provincial cities. The regional industrial centers, including Ekaterinburg, Kharkiv or Ivanovo, were rebuilt in the constructivist manner; some cities, like Magnitogorsk or Zaporizhia, were constructed anew (the so-called socgorod, or 'socialist city').

The style fell markedly out of favor in the 1930s, replaced by the more grandiose nationalist styles that Stalin favored. Constructivist architects and even Le Corbusier projects for the new Palace of the Soviets from 1931 to 1933, but the winner was an early Stalinist building in the style termed Postconstructivism. The last major Russian constructivist building, by Boris Iofan, was built for the Paris World Exhibition (1937), where it faced the pavilion of Nazi Germany by Hitler's architect Albert Speer.[34]

Modernism becomes a movement: CIAM (1928)

By the late 1920s, modernism had become an important movement in Europe. Architecture, which previously had been predominantly national, began to become international. The architects traveled, met each other, and shared ideas. Several modernists, including Le Corbusier, had participated in the competition for the headquarters of the League of Nations in 1927. In the same year, the German Werkbund organized an architectural exposition at the Weissenhof Estate Stuttgart. Seventeen leading modernist architects in Europe were invited to design twenty-one houses; Le Corbusier, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe played a major part. In 1927 Le Corbusier, Pierre Chareau and others proposed the foundation of an international conference to establish the basis for a common style. The first meeting of the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne or International Congresses of Modern Architects (CIAM), was held in a chateau on Lake Leman in Switzerland June 26–28, 1928. Those attending included Le Corbusier, Robert Mallet-Stevens, Auguste Perret, Pierre Chareau and Tony Garnier from France; Victor Bourgeois from Belgium; Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn, Ernst May and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe from Germany; Josef Frank from Austria; Mart Stam and Gerrit Rietveld from the Netherlands, and Adolf Loos from Czechoslovakia. A delegation of Soviet architects was invited to attend, but they were unable to obtain visas. Later members included Josep Lluís Sert of Spain and Alvar Aalto of Finland. No one attended from the United States. A second meeting was organized in 1930 in Brussels by Victor Bourgeois on the topic "Rational methods for groups of habitations". A third meeting, on "The functional city", was scheduled for Moscow in 1932, but was cancelled at the last minute. Instead the delegates held their meeting on a cruise ship traveling between Marseille and Athens. On board, they together drafted a text on how modern cities should be organized. The text, called The Athens Charter, after considerable editing by Corbusier and others, was finally published in 1957 and became an influential text for city planners in the 1950s and 1960s. The group met once more in Paris in 1937 to discuss public housing and was scheduled to meet in the United States in 1939, but the meeting was cancelled because of the war. The legacy of the CIAM was a roughly common style and doctrine which helped define modern architecture in Europe and the United States after World War II.[35]

Art Deco

Pavilion of the Galeries Lafayette Department Store at the Paris International Exposition of Decorative Arts (1925)

The Grand Rex movie theater in Paris (1932)

La Samaritaine department store, by Henri Sauvage, Paris, (1925–28)

The Art Deco architectural style (called Style Moderne in France), was modern, but it was not modernist; it had many features of modernism, including the use of reinforced concrete, glass, steel, chrome, and it rejected traditional historical models, such as the Beaux-Arts style and Neo-classicism; but, unlike the modernist styles of Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, it made lavish use of decoration and color. It reveled in the symbols of modernity; lightning flashes, sunrises, and zig-zags. Art Deco had begun in France before World War I and spread through Europe; in the 1920s and 1930s it became a highly popular style in the United States, South America, India, China, Australia and Japan. In Europe, Art Deco was particularly popular for department stores and movie theaters. The style reached its peak in Europe at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in 1925, which featured art deco pavilions and decoration from twenty countries. Only two pavilions were purely modernist; the Esprit Nouveau pavilion of Le Corbusier, which represented his idea for a mass-produced housing unit, and the pavilion of the USSR, by Konstantin Melnikov in a flamboyantly futurist style.[36]

Later French landmarks in the Art Deco style included the Grand Rex movie theater in Paris, La Samaritaine department store by Henri Sauvage (1926–28) and the Social and Economic Council building in Paris (1937–38) by Auguste Perret, and the Palais de Tokyo and Palais de Chaillot, both built by collectives of architects for the 1937 Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne. .[37]

American Art Deco; the skyscraper style (1919–1939)

The American Radiator Building in New York City by Raymond Hood (1924)

Guardian Building in Detroit, by Wirt C. Rowland (1927–29)

Chrysler Building in New York City, by William Van Alen (1928–30)

Crown of the General Electric Building (also known as 570 Lexington Avenue) by Cross & Cross (1933)

30 Rockefeller Center, now the Comcast Building, by Raymond Hood (1933)

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, an exuberant American variant of Art Deco appeared in the Chrysler Building, Empire State Building and Rockefeller Center in New York City, and Guardian Building in Detroit. The first skyscrapers in Chicago and New York had been designed in a neo-gothic or neoclassical style, but these buildings were very different; they combined modern materials and technology (stainless steel, concrete, aluminum, chrome-plated steel) with Art Deco geometry; stylized zig-zags, lightning flashes, fountains, sunrises, and, at the top of the Chrysler building, Art Deco "gargoyles" in the form of stainless steel radiator ornaments. The interiors of these new buildings, sometimes termed Cathedrals of Commerce", were lavishly decorated in bright contrasting colors, with geometric patterns variously influenced by Egyptian and Mayan pyramids, African textile patterns, and European cathedrals, Frank Lloyd Wright himself experimented with Mayan Revival, in the concrete cube-based Ennis House of 1924 in Los Angeles. The style appeared in the late 1920s and 1930s in all major American cities. The style was used most often in office buildings, but it also appeared in the enormous movie palaces that were built in large cities when sound films were introduced.[38]

Streamline style and Public Works Administration (1933–1939)

Pan-Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles (1936)

The San Francisco Maritime Museum, originally was a public bath house (1936)

Intake towers of Hoover Dam (1931–36)

Long Beach Main Post Office (1933–34)

The beginning of the Great Depression in 1929 brought an end to lavishly-decorated Art Deco architecture and a temporary halt to the construction of new skyscrapers. It also brought in a new style, called "Streamline Moderne" or sometimes just Streamline. This style, sometimes modeled after for the form of ocean liners, featured rounded corners, strong horizontal lines, and often nautical features, such as superstructures and steel railings. It was associated with modernity and especially with transportation; the style was often used for new airport terminals, train and bus stations, and for gas stations and diners built along the growing American highway system. In the 1930s the style was used not only in buildings, but in railroad locomotives, and even refrigerators and vacuum cleaners. It both borrowed from industrial design and influenced it.[39]

In the United States, the Great Depression led to a new style for government buildings, sometimes called PWA Moderne, for the Public Works Administration, which launched gigantic construction programs in the U.S. to stimulate employment. It was essentially classical architecture stripped of ornament, and was employed in state and federal buildings, from post offices to the largest office building in the world at that time, Pentagon (1941–43), begun just before the United States entered the Second World War.[40]

American modernism - Frank Lloyd Wright, Rudolph Schindler, Richard Neutra (1919–1939)

Ennis House in Los Angeles, by Frank Lloyd Wright (1924)

Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright (1928–34)

Lovell Beach House in Newport Beach by Rudolph Schindler (1926)

Lovell House in Los Angeles, California, by Richard Neutra (1927–29)

During the 1920s and 1930s, Frank Lloyd Wright resolutely refused to associate himself with any architectural movements. He considered his architecture to be entirely unique and his own. Between 1916 and 1922, he broke away from his earlier prairie house style and worked instead on houses decorated with textured blocks of cement; this became known as his "Mayan style", after the pyramids of the ancient Mayan civilization. He experimented for a time with modular mass-produced housing. He identified his architecture as "Usonian", a combination of USA, "utopian" and "organic social order". His business was severely affected by the beginning of the Great Depression that began in 1929; he had fewer wealthy clients who wanted to experiment. Between 1928 and 1935, he built only two buildings: a hotel near Chandler, Arizona, and the most famous of all his residences, Fallingwater (1934–37), a vacation house in Pennsylvania for Edgar J. Kaufman. Fallingwater is a remarkable structure of concrete slabs suspended over a waterfall, perfectly uniting architecture and nature.[41]

The Austrian architect Rudolph Schindler designed what could be called the first house in the modern style in 1922, the Schindler house.

Schindler also contributed to American modernism with his design for the Lovell beach house in Newport Beach. The Austrian architect Richard Neutra moved to the United States in 1923, worked for short time with Frank Lloyd Wright, also quickly became a force in American architecture through his modernist design for the same client, the Lovell House in Los Angeles.

Paris International Exposition of 1937 and the architecture of dictators

The Palais de Chaillot by Louis-Hippolyte Boileau, Jacques Carlu and Léon Azéma from the 1937 Paris International Exposition

The Pavilion of Nazi Germany (left) faced the Pavilion of Stalin's Soviet Union (right) at the 1937 Paris Exposition.

Reconstruction of the Pavilion of the Second Spanish Republic by Josep Lluis Sert (1937) displayed Picasso's painting Guernica' (1937)

The Zeppelinfield stadium in Nuremberg, Germany (1934), built by Albert Speer for Nazi Party rallies

The Casa del Fascio (House of Fascism) in Como, Italy, by Giuseppe Terragni (1932–1936)

Palais de Tokyo, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

The 1937 Paris International Exposition in Paris effectively marked the end of the Art Deco, and of pre-war architectural styles. Most of the pavilions were in a neoclassical Deco style, with colonnades and sculptural decoration. The pavilions of Nazi Germany, designed by Albert Speer, in a German neoclassical style topped by eagle and swastika, faced the pavilion of the Soviet Union, topped by enormous statues of a worker and a peasant carrying a hammer and sickle. As to the modernists, Le Corbusier was practically, but not quite invisible at the Exposition; he participated in the Pavilion des temps nouveaux, but focused mainly on his painting.[42] The one modernist who did attract attention was a collaborator of Le Corbusier, Josep Lluis Sert, the Spanish-Catalan architect, whose pavilion of the Second Spanish Republic was pure modernist glass and steel box. Inside it displayed the most modernist work of the Exposition, the painting Guernica by Pablo Picasso. The original building was destroyed after the Exposition, but it was recreated in 1992 in Barcelona.

The rise of nationalism in the 1930s was reflected in the Fascist architecture of Italy, and Nazi architecture of Germany, based on classical styles and designed to express power and grandeur. The Nazi architecture, much of it designed by Albert Speer, was intended to awe the spectators by its huge scale. Adolf Hitler intended to turn Berlin into the capital of Europe, more grand than Rome or Paris. The Nazis closed the Bauhaus, and the most prominent modern architects soon departed for Britain or the United States. In Italy, Benito Mussolini wished to present himself as the heir to the glory and empire of ancient Rome.[43] Mussolini's government was not as hostile to modernism as The Nazis; the spirit of Italian Rationalism of the 1920s continued, with the work of architect Giuseppe Terragni His Casa dl Fascio in Como, headquarters of the local Fascist party, was a perfectly modernist building, with geometric proportions (33.2 meters long by 16.6 meters high); a clean facade of marble, and a Renaissance-inspired interior courtyard. Opposed to Terragni was Marcello Piacitini, a proponent of monumental fascist architecture, who rebuilt the University of Rome, and designed the Italian pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exposition, and planned a grand reconstruction of Rome on the fascist model.[44]

New York World's Fair (1939)

The Trylon and Perisphere, symbols of the 1939 World's Fair

Pavilion of the Ford Motor Company, in the Streamline Moderne style

The RCA Pavilion featured the first public television broadcasts

Living room of the House of Glass, showing what future homes would look like

The 1939 New York World's Fair marked a turning point in architecture between the Art Deco and modern architecture. The theme of the Fair was the World of Tomorrow, and its symbols were the purely geometric trilon and perisphere sculpture. It had many monuments to Art Deco, such as the Ford Pavilion in the Streamline Moderne style, but also included the new International Style that would replace Art Deco as the dominant style after the War. The Pavilions of Finland, by Alvar Aalto, of Sweden by Sven Markelius, and of Brazil by Oscar Niemeyer and Lucio Costa, looked forward to a new style. They became leaders in the postwar modernist movement.[45]

World War II: wartime innovation and postwar reconstruction (1939–1945)

The center of Le Havre destroyed by bombing in 1944

The center of Le Havre as reconstructed by Auguste Perret (1946–1964)

Quonset hut en route to Japan (1945)

World War II (1939–1945) and its aftermath was a major factor in driving innovation in building technology, and in turn, architectural possibilities.[40][46] The wartime industrial demands resulted in shortages of steel and other building materials, leading to the adoption of new materials, such as aluminum, The war and postwar period brought greatly expanded use of prefabricated building; largely for the military and government. The semi-circular metal Nissen hut of World War I was revived as the Quonset hut. The years immediately after the war saw the development of radical experimental houses, including the enameled-steel Lustron house (1947–1950), and Buckminster Fuller's experimental aluminum Dymaxion House.[46][47]

The unprecedented destruction caused by the war was another factor in the rise of modern architecture. Large parts of major cities, from Berlin, Tokyo and Dresden to Rotterdam and east London; all the port cities of France, particularly Le Havre, Brest, Marseille, Cherbourg had been destroyed by bombing. In the United States, little civilian construction had been done since the 1920s; housing was needed for millions of American soldiers returning from the war. The postwar housing shortages in Europe and the United States led to the design and construction of enormous government-financed housing projects, usually in run-down center of American cities, and in the suburbs of Paris and other European cities, where land was available,

One of the largest reconstruction projects was that of the city center of Le Havre, destroyed by the Germans and by Allied bombing in 1944; 133 hectares of buildings in the center were flattened, destroying 12,500 buildings and leaving 40,000 persons homeless. The architect Auguste Perret, a pioneer in the use of reinforced concrete and prefabricated materials, designed and built an entirely new center to the city, with apartment blocks, cultural, commercial and government buildings. He restored historic monuments when possible, and built a new church, St. Joseph, with a lighthouse-like tower in the center to inspire hope. His rebuilt city was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2005.[48]

Le Corbusier and the Cité Radieuse (1947–1952)

Exterior of the Unité d'Habitation, or Cité Radieuse in Marseille (1947–52)

Salon and Terrace of an original unit of the Unité d'Habitation, now at the Cité de l'Architecture et du Patrimoine in Paris (1952)

The Chapel of Notre-Dame-du-Haut in Ronchamp (1950–1955)

Shortly after the War, the French architect Le Corbusier, who was nearly sixty years old and had not constructed a building in ten years, was commissioned by the French government to construct a new apartment block in Marseille. He called it Unité d'Habitation in Marseille, but it more popularly took the name of the Cité Radieuse, after his book about futuristic urban planning. Following his doctrines of design, the building had a concrete frame raised up above the street on pylons. it contained 337 duplex apartment units, fit into the framework like pieces of a puzzle. Each unit had two levels and a small terrace. Interior "streets" had shops, a nursery school and other serves, and the flat terrace roof had a running track, ventilation ducts, and a small theater. Le Corbusier designed furniture, carpets and lamps to go with the building, all purely functional; the only decoration was a choice of interior colors that Le Corbusier gave to residents. Unité d'Habitation became a prototype for similar buildings in other cities, both in France and Germany. Combined with his equally radical organic design for the Chapel of Notre-Dame du-Haut at Ronchamp, this work propelled Corbusier in the first rank of postwar modern architects.[49]

Postwar modernism in the United States (1945–1985)

The international Style of architecture had appeared in Europe, particularly in the Bauhaus movement, in the late 1920s. In 1932 it was recognized and given a name at an Exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City organized by architect Philip Johnson and architectural critic Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Between 1937 and 1941, following the rise Hitler and the Nazis in Germany, most of the leaders of the German Bauhaus movement found a new home in the United States, and played an important part in the development of American modern architecture.

Frank Lloyd Wright and the Guggenheim Museum

The Pfeiffer Chapel at Florida Southern College by Frank Lloyd Wright (1941–1958)

The tower of the Johnson Wax Headquarters and Research Center (1944–50)

The Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma (1956)

Solomon Guggenheim Museum, by Frank Lloyd Wright (1946–1959)

Frank Lloyd Wright was eighty years old in 1947; he had been present at the beginning of American modernism, and though he refused to accept that he belonged to any movement, continued to play a leading role almost to its end. One of his most original late projects was the campus of Florida Southern College in Lakeland, Florida, begun in 1941 and completed in 1943. He designed nine new buildings in a style that he described as "The Child of the Sun". He wrote that he wanted the campus to "grow out of the ground and into the light, a child of the sun."

He completed several notable projects in the 1940s, including the Johnson Wax Headquarters and the Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma (1956). The building is unusual that it is supported by its central core of four elevator shafts; the rest of the building is cantilevered to this core, like the branches of a tree. Wright originally planned the structure for an apartment building in New York City. That project was cancelled because of the Great Depression, and he adapted the design for an oil pipeline and equipment company in Oklahoma. He wrote that in New York City his building would have been lost in a forest of tall buildings, but that in Oklahoma it stood alone. The design is asymmetrical; each side is different.

In 1943 he was commissioned by the art collector Solomon R. Guggenheim to design a museum for his collection of modern art. His design was entirely original; a bowl-shaped building with a spiral ramp inside that led museum visitors on an upward tour of the art of the 20th century. Work began in 1946 but it was not completed until 1959, the year that he died.[45]

Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer

Story Hall of the Harvard Law School by Walter Gropius and (The Architects Collaborative)

The Stillman House Litchfield, Connecticut, by Marcel Breuer (1950) The swimming pool mural is by Alexander Calder

The PanAm building (Now MetLife Building) in New York, by Walter Gropius and The Architects Collaborative (1958–63)

Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus, moved to England in 1934 and spent three years there before being invited to the United States by Walter Hudnut of the Harvard Graduate School of Design; Gropius became the head of the architecture faculty. Marcel Breuer, who had worked with him at the Bauhaus, joined him and opened an office in Cambridge. The fame of Gropius and Breuer attracted many students, who themselves became famous architects, including Ieoh Ming Pei and Philip Johnson. They did not receive an important commission until 1941, when they designed housing for workers in Kensington, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh., In 1945 Gropius and Breuer associated with a group of younger architects under the name TAC (The Architects Collaborative). Their notable works included the building of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, the U.S. Embassy in Athens (1956–57), and the headquarters of Pan American Airways in New York (1958–63). [50]

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Barcelona Pavilion, by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe was the German Pavilion for the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition

The Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois (1945–51)

Crown Hall at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago (1956)

The Seagram Building, New York City, 1958, by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe described his architecture with the famous saying, "Less is more". As the director of the school of architecture of what is now called the Illinois Institute of Technology from 1939 to 1956, Mies (as he was commonly known) made Chicago the leading city for American modernism in the postwar years. He constructed new buildings for the Institute in modernist style, two high-rise apartment buildings on Lakeshore Drive (1948–51), which became models for high-rises across the country. Other major works included Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois (1945–1951), a simple horizontal glass box that had an enormous influence on American residential architecture. The Chicago Convention Center (1952–54) and Crown Hall at the Illinois Institute of Technology (1950–56), and The Seagram Building in New York City (1954–58) also set a new standard for purity and elegance. Based on granite pillars, the smooth glass and steel walls were given a touch of color by the use of bronze-toned I-beams in the structure. He returned to Germany in 1962-68 to build the new Nationalgallerie in Berlin. His students and followers included Philip Johnson, and Eero Saarinen, whose work was substantially influenced by his ideas.[51]

Richard Neutra and Charles & Ray Eames

Eames House by Charles and Ray Eames, Pacific Palisades, (1949)

Neutra Office Building by Richard Neutra in Los Angeles (1950)

The Constance Perkins House by Richard Neutra, Los Angeles (1962)

Influential residential architects in the new style in the United States included Richard Neutra and Charles and Ray Eames. The most celebrated work of the Eames was Eames House in Pacific Palisades, California, (1949) Charles Eames in collaboration with Eero Saarinen It is composed of two structures, an architects residence and his studio, joined in the form of an L. The house, influenced by Japanese architecture, is made of translucent and transparent panels organized in simple volumes, often using natural materials, supported on a steel framework. The frame of the house was assembled in sixteen hours by five workmen. He brightened up his buildings with panels of pure colors.[52]

Richard Neutra continued to build influential houses in Los Angeles, using the theme of the simple box. Many of these houses erased the line distinction between indoor and outdoor spaces with walls of plate glass.[53] Neutra's Constance Perkins House in Pasadena, California (1962) was re-examination of the modest single-family dwelling. It was built of inexpensive material–wood, plaster, and glass–and completed at a cost of just under $18,000. Neutra scaled the house to the physical dimensions of its owner, a small woman. It features a reflecting pool which meanders under of the glass walls of the house. One of Neutra's most unusual buildings was Shepherd's Grove in Garden Grove, California, which featured an adjoining parking lot where worshippers could follow the service without leaving their cars.

Skidmore, Owings and Merrill and Wallace K. Harrison

Lever House by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (1951–52)

Manufacturers Trust Company Building, by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, New York City (1954)

Beinecke Library at Yale University by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (1963)

United Nations Headquarters in New York, by Wallace Harrison with Oscar Niemeyer and Le Corbusier (1952)

The Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center in New York City by Wallace Harrison (1966)

Many of the notable modern buildings in the postwar years were produced by two architectural mega-agencies, which brought together large teams of designers for very complex projects. The firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill was founded in Chicago in 1936 by Louis Skidmore and Nathaniel Owings, and joined in 1939 by engineer John Merrill, It soon went under the name of SOM. Its first big project was Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, the gigantic government installation that produced plutonium for the first nuclear weapons. In 1964 the firm had eighteen "partner-owners", 54 "associate participants,"and 750 architects, technicians, designers, decorators, and landscape architects. Their style was largely inspired by the work of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and their buildings soon had a large place in the New York skyline, including the Lever House (1951-52) and the Manufacturers Trust Company Building (1954). Later buildings by the firm include Beinecke Library at Yale University (1963), the Willis Tower, formerly Sears Tower in Chicago (1973) and One World Trade Center in New York City (2013), which replaced the building destroyed in the terrorist attack of September 11, 2001.[54]

Wallace Harrison played a major part in the modern architectural history of New York; as the architectural advisor of the Rockefeller Family, he helped design Rockefeller Center, the major Art Deco architectural project of the 1930s. He was supervising architect for the 1939 New York World's Fair, and, with his partner Max Abramowitz, was the builder and chief architect of the United Nations Building; Harrison headed a committee of international architects, which included Oscar Niemeyer (who produced the original plan approved by the committee) and Le Corbusier, Other landmark New York buildings designed by Harrison and his firm included Metropolitan Opera House, the master plan for Lincoln Center, and John F. Kennedy Airport.[55]

Philip Johnson

The Glass House by Philip Johnson in New Canaan, Connecticut (1953)

The IDS Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, by Philip Johnson (1969–72)

The Crystal Cathedral by Philip Johnson (1977–80)

The Williams Tower in Houston, Texas, by Philip Johnson (1981–1983)

PPG Place in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, by Philip Johnson (1981–84)

Philip Johnson (1906-2005) was one of the youngest and last major figures in American modern architecture. He trained at Harvard with Walter Gropius, then was director of the department of architecture and modern design at the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1946 to 1954. In 1947, he published a book about Mies van der Rohe, and in 1953 designed his own residence, the Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut in a style modeled after Mies's Farnsworth House. Beginning in 1955 he began to go in his own direction, moving gradually toward expressionism with designs that increasingly departed from the orthodoxies of modern architecture. His final and decisive break with modern architecture was the AT&T Building (later known as the Sony Tower, and now the 550 Madison Avenue in New York City, (1979) an essentially modernist skyscraper completely altered by the addition of curved cap at the top of a piece of chippendale furniture. This building is generally considered to mark the beginning of Postmodern architecture in the United States.[55]

Eero Saarinen

The Gateway Arch in Saint Louis, Missouri (1948–1965)

Main building of the General Motors Technical Center (1949–55)

The Ingalls Rink in New Haven, Connecticut (1953–58)

The TWA Terminal at JFK Airport in New York, by Eero Saarinen (1956–62)

Eero Saarinen (1910–1961) was the son of Eliel Saarinen, the most famous Finnish architect of the Art Nouveau period, who emigrated to the United States in 1923, when Eero was thirteen. He studied art and sculpture at the academy where his father taught, and then at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière Academy in Paris before studying architecture at Yale University. His architectural designs were more like enormous pieces of sculpture than traditional modern buildings; he broke away from the elegant boxes inspired by Mies van der Rohe and used instead sweeping curves and parabolas, like the wings of birds. In 1948 he conceived the idea of a monument in St. Louis, Missouri in the form of a parabolic arch 192 meters high, made of stainless steel (1948). He then designed the General Motors Technical Center in Warren, Michigan (1949–55), a glass modernist box in the style of Mies van der Rohe, followed by the IBM Research Center in Yorktown, Virginia (1957–61). His next works were a major departure in style; he produced a particularly striking sculptural design for the Ingalls Rink in New Haven, Connecticut (1956–59, an ice skiing rink with a parabolic roof suspended from cables, which served as a preliminary model for next and most famous work, the TWA Terminal at JFK airport in New York (1956–1962). His declared intention was to design a building that was distinctive and memorable, and also one that would capture the particular excitement of passengers before a journey. The structure is separated into four white concrete parabolic vaults, which together resemble a bird on the ground perched for flight. Each of the four curving roof vaults has two sides attached to columns in a Y form just outside the structure. One of the angles of each shell is lightly raised, and the other is attached to the center of the structure. The roof is connected with the ground by curtain walls of glass. All of the details inside the building, including the benches, counters, escalators and clocks, were designed in the same style. [56]

Louis Kahn

The First Unitarian Church of Rochester by Louis Kahn (1962)

The Salk Institute by Louis Kahn (1962–63)

Richards Medical Research Laboratories by Louis Kahn (1957–61)

The Kimball Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas (1966–72)

The National Parliament Building in Dhaka, Bangladesh (1962–74)

Louis Kahn (1901–74) was another American architect who moved away from the Mies van der Rohe model of the glass box, and other dogmas of the prevailing international style. He borrowed from a wide variety of styles, and idioms, including neoclassicism. He was professor of architecture at Yale University from 1947–57, where his students included Eero Saarinen. From 1957 until his death he was professor of architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. His work and ideas influenced Philip Johnson, Minoru Yamasaki, and Edward Durell Stone as they moved toward a more neoclassical style. Unlike Mies, he did not try to make his buildings look light; he constructed mainly with concrete and brick, and made his buildings look monumental and solid. He drew from a wide variety of different sources; the towers of Richards Medical Research Laboratories were inspired by the architecture of the Renaissance towns he had seen in Italy as a resident architect at the American Academy in Rome in 1950. Notable buildings by Kahn in the United States include the First Unitarian Church of Rochester, New York (1962); and the Kimball Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas (1966–72). Following the example of Le Corbusier and his design of the government buildings in Chandigarh, the capital city of the Haryana & Punjab State of India, Kahn designed the Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban (National Assembly Building) in Dhaka, Bangladesh (1962–74), when that country won independence from Pakistan. It was Kahn's last work.[57]

I. M. Pei

Green Building at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by I. M. Pei (1962–64)

The National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado by I. M. Pei (1963–67)

Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York by I. M. Pei (1973)

East Wing of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., by I M. Pei (1978)

Pyramid of the Louvre Museum in Paris by I. M. Pei (1983–89)

I. M. Pei (born 1917) is a major figure in late modernism and the debut of Post-modern architecture. He was born in China and educated in the United States, studying architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While the architecture school there still trained in the Beaux-Arts architecture style, Pei discovered the writings of Le Corbusier, and a two-day visit by Le Corbusier to the campus in 1935 had a major impact on Pei's ideas of architecture. In the late 1930s he moved to the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where he studied with Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer and became deeply involved in Modernism.[58] After the War he worked on large projects for the New York real estate developer William Zeckendorf, before breaking away and starting his own firm. One of the first buildings his own firm designed was the Green Building at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While the clean modernist facade was admired, the building developed an unexpected problem; it created a wind-tunnel effect, and in strong winds the doors could not be opened. Pei was forced to construct a tunnel so visitors could enter the building during high winds.

Between 1963 and 1967 Pei designed the Mesa Laboratory for the National Center for Atmospheric Research outside Boulder, Colorado, in an open area at the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. The project differed from Pei's earlier urban work; it would rest in an open area in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. His design was a striking departure from traditional modernism; it looked as if it were carved out of the side of the mountain.[59]

In the late modernist area, art museums bypassed skyscrapers as the most prestigious architectural projects; they offered greater possibilities for innovation in form and more visibility. Pei established himself with his design for the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York (1973), which was praised for its imaginative use of a small space, and its respect for the landscape and other buildings around it. This led to the commission for one of the most important museum projects of the period, the new East Wing of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, completed in 1978, and to another of Pei's most famous projects, the pyramid at the entrance of Louvre Museum in Paris (1983–89). Pei chose the pyramid as the form that best harmonized with the Renaissance and neoclassical forms of the historic Louvre., as well as for its associations with Napoleon and the Battle of the Pyramids. Each face of the pyramid is supported by 128 beams of stainless steel, supporting 675 panels of glass, each 2.9 by 1.9 meters.[60]

Postwar modernism in Europe (1945–1975)

Sainte Marie de La Tourette in Evreaux-sur-l'Arbresle, France by Le Corbusier (1956–60)

Royal National Theatre, London, by Denys Lasdun (1967–1976)

Auditorium of the University of Technology, Helsinki, by Alvar Aalto (1964)

University Hospital Center in Liege, Belgium by Charles Vandenhove (1962–82)

The Pirelli Tower in Milan, by Gio Ponti and Pier Luigi Nervi (1958–60)

The Fondation Maeght by Josep Lluis Sert (1959–1964)

Church of St. Martin, Idstein Germany by Johannes Krahn (1965)

Warszawa Centralna railway station in Poland by Arseniusz Romanowicz (1975)

In France, Le Corbusier remained the most prominent architect, though he built few buildings there. His most prominent late work was the convent of Sainte Marie de La Tourette in Evreaux-sur-l'Arbresle. The Convent, built of raw concrete, was austere and without ornament, inspired by the medieval monasteries he had visited on his first trip to Italy. [61]

In Britain, the major figures in modernism included James Stirling (1926–1992) and Denys Lasdun (1914–2001). Lasdun's best-known work is the Royal National Theatre (1967–1976) on the south bank of the Thames. Its raw concrete and blockish form offended British traditionalists; Charles, Prince of Wales Prince Charles compared it with a nuclear power station.

In Belgium, a major figure was Charles Vandenhove (born 1927) who constructed an important series of buildings for the University Hospital Center in Liege. His later work ventured into colorful rethinking of historical styles, such as Palladian architecture.[62]

In Finland, the most influential architect was Alvar Aalto, who adapted his version of modernism to the Nordic landscape, light, and materials, particularly the use of wood. After World War II, he taught architecture in the United States. In Sweden, Arne Jacobsen was the best-known of the modernists, who designed furniture as well as carefully-proportioned buildings.

In Italy, the most prominent modernist was Gio Ponti, who worked often with the structural engineer Pier Luigi Nervi, a specialist in reinforced concrete. Nervi created concrete beams of exceptional length, twenty-five meters, which allowed greater flexibility in forms and greater heights. Their best-known design was the Pirelli Building in Milan (1958–1960), which for decades was the tallest building in Italy.[63]

The most famous Spanish modernist was the Catalan architect Josep Lluis Sert, who worked with great success in Spain, France and the United States. In his early career he worked for a time under Le Corbusier, and designed the Spanish pavilion for the 1937 Paris Exposition. His notable later work included the Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul-de-Provence, France (1964), and the Harvard Science Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He served as Dean of Architecture at the Harvard School of Design.

Notable German modernists included Johannes Krahn, who played an important part in rebuilding German cities after World War II, and built several important museums and churches, notably St. Martin, Idstein, which artfully combined stone masonry, concrete and glass. Leading Austrian architects of the style included Gustav Peichl, whose later works included the Art and Exhibition Center of the German Federal Republic in Bonn, Germany (1989).

Latin America

Ministry of Health and Education in Rio de Janeiro by Lucio Costa (1936–43)

MAM Rio museum, by Affonso Eduardo Reidy (1960)

The National Congress building in Brasilia by Oscar Niemeyer (1956–61)

The Cathedral of Brasilia by Oscar Niemeyer (1958–1970)

The Palácio do Planalto, offices of the Brazilian president, by Oscar Niemeyer (1958–60)

The Torre Latinoamericana in Mexico City by Augusto H. Alvarez (1956)

The Colegio de México in Mexico City by Teodoro González de León and Abraham Zabludovsky (1976)

Interior of the Luis Barragán House and Studio in Mexico City, by Luis Barragan (1948)

Brazil became a showcase of modern architecture in the late 1930s through the work of Lucio Costa (1902–1998) and Oscar Niemeyer (1907–2012). Costa had the lead and Niemeyer collaborated on the Ministry of Education and Health in Rio de Janeiro (1936–43) and the Brazilian pavilion at the 1939 World's Fair in New York. Following the war, Niemeyer, along with Le Corbusier, conceived the form of the United Nations Headquarters constructed by Walter Harrison.

Lucio Costa also had overall responsibility for the plan of the most audacious modernist project in Brazil; the creation of a new capital, Brasilia, constructed between 1956 and 1961. Costa made the general plan, laid out in the form of a cross, with the major government buildings in the center. Niemeyer was responsible for designing the government buildings, including the palace of the President;the National Assembly, composed of two towers for the two branches of the legislature and two meeting halls, one with a cupola and other with an inverted cupola. Niemeyer also built the cathedral, eighteen ministries, and giant blocks of housing, each designed for three thousand residents, each with its own school, shops, and chapel. Modernism was employed both as an architectural principle and as a guideline for organizing society, as explored in The Modernist City.[64]

Following a military coup d'état in Brazil in 1964, Niemeyer moved to France, where he designed the modernist headquarters of the French Communist Party in Paris (1965–1980), a miniature of his United Nations plan.[65]

Mexico also had a prominent modernist movement. Important figures included Félix Candela, born in Spain, who emigrated to Mexico in 1939, and participated in the construction of the new University of Mexico City; he specialized in concrete structures in unusual parabolic forms. Another important figure was Mario Pani, who designed the National Conservatory of Music in Mexico City (1949), and the Torre Insignia (1988). Augusto H. Alvarez designed the Torre Latinamericano, one of the early modernist skyscrapers in Mexico City (1956); it successfully withstood the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, which destroyed many other buildings in the city center. 1964. Pedro Ramirez Vasquez and Rafael Mijares designed the Olympic Stadium for the 1968 Olympics, and Antoni Peyri and Candela designed the Palace of Sports. Luis Barragan was another influential figure in Mexican modernism; his raw concrete residence and studio in Mexico City looks like a blockhouse on the outside, while inside it features great simplicity in form, pure colors, abundant natural light, and, one of is signatures, a stairway without a railing. He won the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1980, and the house was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2004.[66]

Asia and the Pacific

House of Kunio Maekawa in Tokyo (1935)

International House of Japan by Kunio Maekawa, Tokyo (1955)

Yoyogi National Gymnasium by Kenzo Tange (1964)

Sydney Opera House in Sydney, Australia, by Jorn Utzon (1973)

Japan, like Europe, had an enormous shortage of housing after the war, due to the bombing of many cities. 4.2 million housing units needed to be replaced. Japanese architects combined both traditional and styles and techniques. One of the foremost Japanese modernists was Kunio Maekawa (1905–1986), who had worked for Le Corbusier in Paris until 1930. His own house in Tokyo was an early landmark of Japanese modernism, combining traditional style with ideas he acquired working with Le Corbusier. His notable buildings include concert halls in Tokyo and Kyoto and the International House of Japan in Tokyo, all in the pure modernist style.

Kenzo Tange (1913–2005) worked in the studio of Kunio Maekawa from 1938 until 1945 before opening his own architectural firm. His first major commission was the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum . He designed many notable office buildings and cultural centers. office buildings, as well as the Yoyogi National Gymnasium for the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. The gymasim, built of concrete, features a roof suspended over the stadium on steel cables.

The Danish architect Jorn Utzon (1918-) worked briefly with Alvar Aalto, studied the work of Le Corbusier, and traveled to the United States to meet Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1957 he designed one of the most recognizable modernist buildings in the world; the Sydney Opera House.. He is known for the sculptural qualities of his buildings, and their relationship with the landscape. The five concrete shells of the structure resemble seashells by the beach. Begun in 1957, the project encountered considerable technical difficulties making the shells and getting the acoustics right. Utzon resigned in 1966, and the opera house was not finished until 1973, ten years after its scheduled completion. [67]

Preservation

Several works or collections of modern architecture have been designated by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites. In addition to the early experiments associated with Art Nouveau, these include a number of the structures mentioned above in this article: the Rietveld Schröder House in Utrecht, the Bauhaus structures in Weimar and Dessau, the Berlin Modernism Housing Estates, the White City of Tel Aviv, the city of Asmara, the city of Brasilia, the Ciudad Universitaria of UNAM in Mexico City and the University City of Caracas in Venezuela, and the Sydney Opera House.

Private organizations such as Docomomo International, the World Monuments Fund, and the Recent Past Preservation Network are working to safeguard and document imperiled Modern architecture. In 2006, the World Monuments Fund launched Modernism at Risk, an advocacy and conservation program.

See also

- Modernisme

- Modern furniture

- Modern art

- Organic architecture

- Postmodern architecture

- Critical regionalism

- List of post-war Category A listed buildings in Scotland

References

Notes and citations

^ "What is Modern architecture?". Royal Institute of British Architects. Retrieved 15 October 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Tietz 1999, pp. 6-10.

^ Bony 2012, pp. 42-43.

^ Bony 2012, pp. 14-16.

^ ab Encyclopædia Britannica - François Coignet

^ Bony 2012, p. 42.

^ Bony 2012, p. 16.

^ Crouch, Christopher. 2000. "Modernism in Art Design and Architecture", New York: St. Martins Press.

ISBN 0-312-21830-3 (cloth)

ISBN 0-312-21832-X (pbk)

^ Viollet Le-duc, Entretiens sur Architecture

^ Bouillon 1985, p. 24.

^ Bony 2012, p. 27.

^ Bony 2012, p. 33.

^ Poisson, pp. 318-319.

^ Poisson 2009, p. 318.

^ Otto Wagner, Modern Architecture: A Guidebook for His Students to this Field of Art, 1895, translation by Harry Francis Mallgrave, Getty Publications, 1988,

ISBN 0226869393

^ Bony, p. 36.

^ Bony 2012, p. 38.

^ Lucius Burckhardt (1987) . The Werkbund. ? : Hyperion Press. ISBN. Frederic J. Schwartz (1996). The Werkbund: Design Theory and Mass Culture Before the First World War. New Haven, Conn. : Yale University Press. ISBN.

^ Mark Jarzombek. "Joseph August Lux: Werkbund Promoter, Historian of a Lost Modernity," Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 63/1 (June 2004): 202–219.

^ Tietz 1999, p. 19.

^ Tietz 1999, p. 16.

^ Bony 2012, pp. 62-63.

^ Burchard and Brown 1966, p. 83.

^ Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture", (1923), Flammarion edition (1995), pages XVIII-XIX

^ Bony 2012, p. 83.

^ ab Bony 2012, pp. 93-95.

^ Jencks, p. 59

^ Sharp, p. 68

^ Pehnt, p. 163

^ Bony 2012, p. 95.

^ Tietz 1999, pp. 26-27.

^ Bony 2012, pp. 86-87.

^ "Alexey Shchusev (1873-1949)". Retrieved 2015-08-16.

^ Udovički-Selb, Danilo (2012-01-01). "Facing Hitler's Pavilion: The Uses of Modernity in the Soviet Pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exhibition". Journal of Contemporary History. 47 (1): 13–47. doi:10.1177/0022009411422369. ISSN 0022-0094.

^ Bony 2012, pp. 84-85.

^ Anwas, Victor, Art Deco (1992), Harry N. Abrams Inc.,

ISBN 0810919265

^ Poisson, Michel, 1000 Immeubles et Monuments de Paris (2009), Parigramme, pages 318-319 and 300-01

^ Duncan.

^ Ducher 2014, p. 204.

^ ab "Growth, Efficiency, and Modernism" (PDF). U.S. General Services Administration. 2006 [2003]. p. 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-03-31. Retrieved March 2011. Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

^ Bony 2012, p. 99.

^ Journet 2015, p. 216.

^ Frampton, Kenneth (1980). Modern Architecture: A Critical History (3rd ed.). Thames and Hudson. pp. 210–218. ISBN 0-500-20257-5.

^ Bony 2012, pp. 120-121.

^ ab Bony 2012, p. 128.

^ ab Thomas C. Jester, ed. (1995). Twentieth-Century Building Materials. McGraw-Hill. pp. 41–42, 48–49. ISBN 0-07-032573-1.