Isabella of France

| Isabella of France | |

|---|---|

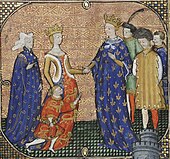

15th century depiction of Isabella | |

| Queen consort of England | |

| Tenure | 25 January 1308 – 25 January 1327 |

| Coronation | 25 February 1308 |

| Born | 1295 Paris, France |

| Died | 22 August 1358 (aged 62–63) Hertford Castle, England[1] |

| Burial | 27 November 1358 Grey Friars' Church at Newgate |

| Spouse | Edward II of England (m. 1308; died 1327) |

| Issue |

|

| House | Capet |

| Father | Philip IV of France |

| Mother | Joan I of Navarre |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Isabella of France (1295 – 22 August 1358), sometimes described as the She-Wolf of France, was Queen of England as the wife of Edward II, and regent of England from 1326 until 1330. She was the youngest surviving child and only surviving daughter of Philip IV of France and Joan I of Navarre. Queen Isabella was notable at the time for her beauty, diplomatic skills, and intelligence.

Isabella arrived in England at the age of 12[2] during a period of growing conflict between the king and the powerful baronial factions. Her new husband was notorious for the patronage he lavished on his favourite, Piers Gaveston, but the queen supported Edward during these early years, forming a working relationship with Piers and using her relationship with the French monarchy to bolster her own authority and power. After the death of Gaveston at the hands of the barons in 1312, however, Edward later turned to a new favourite, Hugh Despenser the Younger, and attempted to take revenge on the barons, resulting in the Despenser War and a period of internal repression across England. Isabella could not tolerate Hugh Despenser and by 1325 her marriage to Edward was at a breaking point.

Travelling to France under the guise of a diplomatic mission, Isabella began an affair with Roger Mortimer, and the two agreed to depose Edward and oust the Despenser family. The Queen returned to England with a small mercenary army in 1326, moving rapidly across England. The King's forces deserted him. Isabella deposed Edward, becoming regent on behalf of her son, Edward III. Many have believed that Isabella then arranged the murder of Edward II. Isabella and Mortimer's regime began to crumble, partly because of her lavish spending, but also because the Queen successfully, but unpopularly, resolved long-running problems such as the wars with Scotland.

In 1330, Isabella's son Edward III deposed Mortimer in turn, taking back his authority and executing Isabella's lover. The Queen was not punished, however, and lived for many years in considerable style—although not at Edward III's court, though she often visited to dote on her grandchildren and was marginally involved in peace talks—until her death in 1358. Isabella became a popular "femme fatale" figure in plays and literature over the years, usually portrayed as a beautiful but cruel, manipulative figure.

Contents

1 Early life and marriage: 1295–1308

2 Queenship

2.1 Fall of Gaveston: 1308–1312

2.2 Tensions grow: 1312–1321

2.3 Return of the Despensers, 1321–1326

3 Invasion of England

3.1 Tensions in Gascony, 1323–1325

3.2 Roger Mortimer, 1325–1326

3.3 Seizure of power, 1326

3.4 Death of Edward, 1327

4 Later years

4.1 As regent, 1326–1330

4.2 Mortimer's fall from power, 1330

4.3 In retirement, 1330–1358

5 Cultural depictions

5.1 Literature and theatre

5.2 Film

6 Issue

7 Arms

8 Ancestry

9 See also

10 Notes

11 Sources

12 External links

Early life and marriage: 1295–1308

Isabella's French family, depicted in 1315: l-r: Isabella's brothers, Charles and Philip, Isabella herself, her father, Philip IV, her brother Louis, and her uncle, Charles of Valois. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Isabella was born in Paris on an uncertain date – on the basis of the chroniclers and the eventual date of her marriage, she was probably born between May and November 1295. She is described as born in 1292 in the Annals of Wigmore, and Piers Langtoft agrees, claiming that she was 7 years old in 1299. The French chronicler Guillaume de Nangis and English chronicler Thomas Walsingham describe her as 12 years old at the time of her marriage in January 1308, placing her birth between January 1295 and of 1296. A papal dispensation by Clement V in November 1305 permitted her immediate marriage by proxy, despite the fact that she was probably only 10 years old. Since she had to reach the canonical age of 7 before her betrothal in May 1303, and that of 12 before her marriage in January 1308, the evidence suggests that she was born between May and November 1295.[3] Her parents were King Philip IV of France and Queen Joan I of Navarre; her brothers Louis, Philip and Charles became kings of France.

Isabella was born into a royal family that ruled the most powerful state in Western Europe. Her father, King Philip, known as "le Bel" (the Fair) because of his good looks, was a strangely unemotional man; contemporaries described him as "neither a man nor a beast, but a statue";[4] modern historians have noted that he "cultivated a reputation for Christian kingship and showed few weaknesses of the flesh".[5] Philip built up centralised royal power in France, engaging in a sequence of conflicts to expand or consolidate French authority across the region, but remained chronically short of money throughout his reign. Indeed, he appeared almost obsessed about building up wealth and lands, something that his daughter was also accused of in later life.[6] Isabella's mother died when Isabella was still quite young; some contemporaries suspected Philip IV of her murder, albeit probably incorrectly.[7]

Seal of Edward II

Isabella was brought up in and around the Château du Louvre and the Palais de la Cité in Paris.[8] Isabella was cared for by Théophania de Saint-Pierre, her nurse, given a good education and taught to read, developing a love of books.[8] As was customary for the period, all of Philip's children were married young for political benefit. Isabella was promised in marriage by her father to Edward, the infant son of King Edward I of England, with the intention to resolve the conflicts between France and England over the latter's continental possession of Gascony and claims to Anjou, Normandy and Aquitaine.[9]Pope Boniface VIII had urged the marriage as early as 1298 but was delayed by wrangling over the terms of the marriage contract. Edward I attempted to break the engagement several times for political advantage, and only after he died in 1307 did the wedding proceed.

Isabella and Edward II were finally married at Boulogne-sur-Mer on 25 January 1308. Isabella's wardrobe gives some indications of her wealth and style – she had gowns of baudekyn, velvet, taffeta and cloth, along with numerous furs; she had over 72 headdresses and coifs; she brought with her two gold crowns, gold and silver dinnerware and 419 yards of linen.[10] At the time of her marriage, Isabella was probably about twelve and was described by Geoffrey of Paris as "the beauty of beauties... in the kingdom if not in all Europe." This description was probably not simply flattery by a chronicler, since both Isabella's father and brothers were considered very handsome men by contemporaries, and her husband was to nickname her "Isabella the Fair".[10] Isabella was said to resemble her father, and not her mother, queen regnant of Navarre, a plump, plain woman.[11] This indicates that Isabella was slender and pale-skinned, although the fashion at the time was for blonde, slightly full-faced women, and Isabella may well have followed this stereotype instead.[12] Throughout her career, Isabella was noted as charming and diplomatic, with a particular skill at convincing people to follow her courses of action.[13] Unusual for the medieval period, contemporaries also commented on her high intelligence.[14]

Queenship

As queen, the young Isabella faced numerous challenges. Edward was handsome, but highly unconventional, possibly forming close romantic attachments to first Piers Gaveston and then Hugh Despenser the younger. Edward found himself at odds with the barons, too, in particular his first cousin Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, whilst continuing the war against the Scots that he had inherited from Edward I. Using her own supporters at court, and the patronage of her French family, Isabella attempted to find a political path through these challenges; she successfully formed an alliance with Gaveston, but after his death at the hands of the barons her position grew increasingly precarious. Edward began to take revenge on his enemies, using an ever more brutal alliance with the Despenser family, in particular his new favourite, Hugh Despenser the younger. By 1326 Isabella found herself at increasing odds with both Edward and Hugh, ultimately resulting in Isabella's own bid for power and the invasion of England.[15]

Fall of Gaveston: 1308–1312

Isabella was able to come to an understanding with her husband's first favourite Piers Gaveston, shown here lying dead at the feet of Guy de Beauchamp, in a 15th-century representation.

Isabella's new husband Edward was an unusual character by medieval standards. Edward looked the part of a Plantagenet king to perfection. He was tall, athletic, and wildly popular at the beginning of his reign.[16] He rejected most of the traditional pursuits of a king for the period – jousting, hunting and warfare – and instead enjoyed music, poetry and many rural crafts.[17] Furthermore, there is the question of Edward's sexuality in a period when homosexuality of any sort was considered a very serious crime, but there is no direct evidence of his sexual orientation. However, contemporary chroniclers made much of his close affinity with a succession of male favourites; some condemned Edward for loving them "beyond measure" and "uniquely", others explicitly referring to an "illicit and sinful union".[18] Nonetheless, Isabella bore four children by Edward, leading to an opinion amongst some historians that Edward's affairs with his male favourites may have been platonic.[18]

When Isabella first arrived in England following her marriage, her husband was already in the midst of a relationship with Piers Gaveston, an "arrogant, ostentatious" soldier, with a "reckless and headstrong" personality that clearly appealed to Edward.[19] Isabella, then aged twelve, was effectively sidelined by the pair. Edward chose to sit with Gaveston rather than Isabella at their wedding celebration,[20] causing grave offence to her uncles Louis, Count of Évreux, and Charles, Count of Valois,[17] and then refused to grant her either her own lands or her own household.[21] Edward also gave Isabella's own jewelry to Gaveston, which he wore publicly.[22] It took the intervention of Isabella's father, Philip IV, before Edward began to provide for her more appropriately.[21]

Isabella's relationship with Gaveston was a complex one. Baronial opposition to Gaveston, championed by Thomas of Lancaster, was increasing, and Philip IV began to covertly fund this grouping, using Isabella and her household as intermediaries.[23] Edward was forced to exile Gaveston to Ireland for a period, and began to show Isabella much greater respect and assigning her significant lands and patronage; in turn, Philip ceased his support for the barons. Gaveston eventually returned from Ireland, and by 1309–11 the three seemed to be co-existing together relatively comfortably.[24] Indeed, Gaveston's key enemy, Thomas of Lancaster, considered Isabella to be an ally of Gaveston's.[24] Isabella had begun to build up her own supporters at court, principally the de Beaumont family, itself opposed to the Lancastrians; originating, like her, from France, the senior member of the family, Isabella de Vesci, had been a close confidant of Edward's mother Eleanor; supported by her brother, Henry de Beaumont, Isabella de Vesci became a close friend of Queen Isabella in turn.[citation needed]

During 1311, however, Edward conducted a failed campaign against the Scots, during which Isabella and he only just escaped capture. In the aftermath, the barons rose up, signing the Ordinances of 1311, which promised action against Gaveston and expelled Isabella de Vesci and Henry de Beaumont from court.[25] 1312 saw a descent into civil war against the king and his lover – Isabella stood with Edward, sending angry letters to her uncles d'Évreux and de Valois asking for support.[25] Edward left Isabella, rather against her will, at Tynemouth Priory in Northumberland whilst he unsuccessfully attempted to fight the barons.[26] The campaign was a disaster, and although Edward escaped, Gaveston found himself stranded at Scarborough Castle, where his baronial enemies first surrounded and captured him. Guy de Beauchamp and Thomas of Lancaster ensured Gaveston's execution as he was being taken south to rejoin Edward.[27]

Tensions grow: 1312–1321

Tensions mounted steadily over the decade. In 1312, Isabella gave birth to the future Edward III, but by the end of the year Edward's court was beginning to change. Edward was still relying upon his French in-laws – Isabella's uncle Louis, for example, had been sent from Paris to assist him – but Hugh Despenser the elder now formed part of the inner circle, marking the beginning of the Despensers' increased prominence at Edward's court.[28] The Despensers were opposed to both the Lancastrians and their other allies in the Welsh Marches, making an easy alliance with Edward, who sought revenge for the death of Gaveston.[29]

In 1313, Isabella travelled to Paris with Edward to garner further French support, which resulted in the Tour de Nesle Affair. The journey was a pleasant one, with lots of festivities, although Isabella was injured when her tent burned down.[30] During the visit Louis and Charles had had a satirical puppet show put on for their guests, and after this Isabella had given new embroidered purses both to her brothers and to their wives.[31] Isabella and Edward then returned to England with new assurances of French support against the English barons. Later in the year, however, Isabella and Edward held a large dinner in London to celebrate their return and Isabella apparently noticed that the purses she had given to her sisters-in-law were now being carried by two Norman knights, Gautier and Philippe d'Aunay.[31] Isabella concluded that the pair must have been carrying on an illicit affair, and appears to have informed her father of this during her next visit to France in 1314.[32] The consequence of this was the Tour de Nesle Affair in Paris, which led to legal action against all three of Isabella's sisters-in-law; Blanche and Margaret of Burgundy were imprisoned for life for adultery. Joan of Burgundy was imprisoned for a year. Isabella's reputation in France suffered somewhat as a result of her perceived role in the affair.

In the north, however, the situation was turning worse. Edward attempted to quash the Scots in a fresh campaign in 1314, resulting in the disastrous defeat at the battle of Bannockburn. Edward was blamed by the barons for the catastrophic failure of the campaign. Thomas of Lancaster reacted to the defeats in Scotland by taking increased power in England and turning against Isabella, cutting off funds and harassing her household.[33] To make matters worse, the "Great Famine" descended on England during 1315–17, causing widespread loss of life and financial problems.[34]

Despite Isabella giving birth to her second son, John, in 1316, Edward's position was precarious. Indeed, John Deydras, a royal Pretender, appeared in Oxford, claiming to have been switched with Edward at birth, and to be the real king of England himself.[35] Given Edward's unpopularity, the rumours spread considerably before Deydras' eventual execution, and appear to have greatly upset Isabella. Isabella responded by deepening her alliance with Lancaster's enemy Henry de Beaumont and by taking up an increased role in government herself, including attending council meetings and acquiring increased lands.[36] Henry's sister, Isabella de Vesci, continued to remain a close adviser to the Queen.[34] The Scottish general Sir James Douglas, war leader for Robert I of Scotland, made a bid to capture Isabella personally in 1319, almost capturing her at York – Isabella only just escaped.[37] Suspicions fell on Lancaster, and one of Edward's knights, Edmund Darel, was arrested on charges of having betrayed her location, but the charges were essentially unproven.[38] In 1320, Isabella accompanied Edward to France, to try and convince her brother, Philip V, to provide fresh support to crush the English barons.[38]

Meanwhile, Hugh de Despenser the younger became an increasing favourite of Isabella's husband, and was widely believed to have begun a sexual relationship with him around this time.[39] Hugh was the same age as Edward. His father, Hugh the elder, had supported Edward and Gaveston a few years previously.[40] The Despensers were bitter enemies of Lancaster, and with Edward's support began to increase their power base in the Welsh Marches, in the process making enemies of Roger Mortimer de Chirk and his nephew, Roger Mortimer of Wigmore, their rival Marcher Lords.[41] Whilst Isabella had been able to work with Gaveston, Edward's previous favourite, it became increasingly clear that Hugh the younger and Isabella could not work out a similar compromise. Unfortunately for Isabella, she was still estranged from Lancaster's rival faction, giving her little room to manoeuvre.[42] In 1321, Lancaster's alliance moved against the Despensers, sending troops into London and demanding their exile. Aymer de Valence, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, a moderate baron with strong French links, asked Isabella to intervene in an attempt to prevent war;[43] Isabella publicly went down on her knees to appeal to Edward to exile the Despensers, providing him with a face-saving excuse to do so, but Edward intended to arrange their return at the first opportunity.[44]

Return of the Despensers, 1321–1326

Despite the momentary respite delivered by Isabella, by the autumn of 1321, the tensions between the two factions of Edward, Isabella and the Despenser, opposing the baronial opposition led by Thomas of Lancaster, were extremely high, with forces still mobilised across the country.[45] At this point, Isabella undertook a pilgrimage to Canterbury, during which she left the traditional route to stop at Leeds Castle in Kent, a fortification held by Bartholomew de Badlesmere, steward of the King's household who had by 1321 joined the ranks of Edward's opponents. Historians believe that the pilgrimage was a deliberate act by Isabella on Edward's behalf to create a casus belli.[46] Lord Badlesmere was away at the time, having left his wife Margaret in charge of the castle. When the latter adamantly refused the Queen admittance, fighting broke out outside the castle between Isabella's guards and the garrison, marking the beginning of the Despenser War.[47] Whilst Edward mobilised his own faction and placed Leeds castle under siege, Isabella was given the Great Seal and assumed control of the royal Chancery from the Tower of London.[47] After surrendering to Edward's forces on 31 October 1321, Margaret, Baroness Badlesmere and her children were sent to the Tower, and 13 of the Leeds garrison were hanged. By January 1322, Edward's army, reinforced by the Despensers returning from exile, had forced the surrender of the Mortimers, and by March Lancaster himself had been captured after the battle of Boroughbridge; Lancaster was promptly executed, leaving Edward and the Despensers victorious.[48]

Tynemouth Priory, seen from the sea, where Isabella escaped the Scots army following the disastrous campaign of 1322.

Hugh Despenser the younger was now firmly ensconced as Edward's new favourite and lover, and together over the next four years Edward and the Despensers imposed a harsh rule over England, a "sweeping revenge"[49] characterised by land confiscation, large-scale imprisonment, executions and the punishment of extended family members, including women and the elderly.[50] This was condemned by contemporary chroniclers, and is felt to have caused concern to Isabella as well;[51] some of those widows being persecuted included her friends.[52] Isabella's relationship with Despenser the younger continued to deteriorate; the Despensers refused to pay her monies owed to her, or return her castles at Marlborough and Devizes.[53] Indeed, various authors have suggested that there is evidence that Hugh Despenser the younger may have attempted to assault Isabella herself in some fashion.[54] Certainly, immediately after the battle of Boroughbridge, Edward began to be markedly less generous in his gifts towards Isabella, and none of the spoils of the war were awarded to her.[55] Worse still, later in the year Isabella was caught up in the failure of another of Edward's campaigns in Scotland, in a way that permanently poisoned her relationship with both Edward and the Despensers.

Isabella and Edward had travelled north together at the start of the autumn campaign; before the disastrous Battle of Old Byland in Yorkshire, Edward had ridden south, apparently to raise more men, sending Isabella east to Tynemouth Priory.[56] With the Scottish army marching south, Isabella expressed considerable concern about her personal safety and requested assistance from Edward. Her husband initially proposed sending Despenser forces to secure her, but Isabella rejected this outright, instead requesting friendly troops. Rapidly retreating south with the Despensers, Edward failed to grip the situation, with the result that Isabella found herself and her household cut off from the south by the Scottish army, with the coastline patrolled by Flemish naval forces allied to the Scots.[57] The situation was precarious and Isabella was forced to use a group of squires from her personal retinue to hold off the advancing army whilst other of her knights commandeered a ship; the fighting continued as Isabella and her household retreated onto the vessel, resulting in the death of two of her ladies-in-waiting.[57] Once aboard, Isabella evaded the Flemish navy, landing further south and making her way to York.[57] Isabella was furious, both with Edward for, from her perspective, abandoning her to the Scots, and with Despensers for convincing Edward to retreat rather than sending help.[58] For his part, Edward blamed Lewis de Beaumont, the Bishop of Durham and an ally of Isabella, for the fiasco.[58]

Isabella effectively separated from Edward from here onwards, leaving him to live with Hugh Despenser. At the end of 1322, Isabella left the court on a ten-month-long pilgrimage around England by herself.[59] On her return in 1323 she visited Edward briefly, but refused to take a loyalty oath to the Despensers and was removed from the process of granting royal patronage.[59] At the end of 1324, as tensions grew with Isabella's homeland of France, Edward and the Despensers confiscated all of Isabella's lands, took over the running of her household and arrested and imprisoned all of her French staff. Isabella's youngest children were removed from her and placed into the custody of the Despensers.[60] At this point, Isabella appears to have realised that any hope of working with Edward was effectively over and begun to consider radical solutions.

Invasion of England

By 1325, Isabella was facing increasing pressure from Hugh Despenser the Younger, Edward's new royal favourite. With her lands in England seized, her children taken away from her and her household staff arrested, Isabella began to pursue other options. When her brother, King Charles IV of France, seized Edward's French possessions in 1325, she returned to France, initially as a delegate of the King charged with negotiating a peace treaty between the two nations. However, her presence in France became a focal point for the many nobles opposed to Edward's reign. Isabella gathered an army to oppose Edward, in alliance with Roger Mortimer, whom she took as a lover. Isabella and Mortimer returned to England with a mercenary army, seizing the country in a lightning campaign. The Despensers were executed and Edward was forced to abdicate – his eventual fate and possible murder remains a matter of considerable historical debate. Isabella ruled as regent until 1330, when her son, Edward deposed Mortimer in turn and ruled directly in his own right.[61]

Tensions in Gascony, 1323–1325

A near-contemporary miniature showing the future Edward III giving homage to Charles IV under the guidance of Edward's mother, and Charles' sister, Isabella, in 1325.[62]

Isabella's husband Edward, as the Duke of Aquitaine, owed homage to the King of France for his lands in Gascony.[63] Isabella's three brothers each had only short reigns, and Edward had successfully avoided paying homage to Louis X, and had only paid homage to Philip V under great pressure. Once Charles IV took up the throne, Edward had attempted to avoid doing so again, increasing tensions between the two.[63] One of the elements in the disputes was the border province of Agenais, part of Gascony and in turn part of Aquitaine. Tensions had risen in November 1323 after the construction of a bastide, a type of fortified town, in Saint-Sardos, part of the Agenais, by a French vassal.[64] Gascon forces destroyed the bastide, and in turn Charles attacked the English-held Montpezat: the assault was unsuccessful,[65] but in the subsequent War of Saint-Sardos Isabella's uncle, Charles of Valois, successfully wrestled Aquitaine from English control;[66] by 1324, Charles had declared Edward's lands forfeit and had occupied the whole of Aquitaine apart from the coastal areas.[67]

Edward was still unwilling to travel to France to give homage; the situation in England was febrile; there had been an assassination plot against Edward and Hugh Despenser in 1324, there had been allegations that the famous magician John of Nottingham had been hired to kill the pair using necromancy in 1325, and criminal gangs were occupying much of the country.[68] Edward was deeply concerned that should he leave England, even for a short while, the barons would take the chance to rise up and take their revenge on the Despensers. Charles sent a message through Pope John XXII to Edward, suggesting that he was willing to reverse the forfeiture of the lands if Edward ceded the Agenais and paid homage for the rest of the lands:[69] the Pope proposed Isabella as an ambassador. Isabella, however, saw this as a perfect opportunity to resolve her situation with Edward and the Despensers.

Having promised to return to England by the summer, Isabella reached Paris in March 1325, and rapidly agreed a truce in Gascony, under which Prince Edward, then thirteen years old, would come to France to give homage on his father's behalf.[70] Prince Edward arrived in France, and gave homage in September. At this point, however, rather than returning, Isabella remained firmly in France with her son. Edward began to send urgent messages to the Pope and to Charles IV, expressing his concern about his wife's absence, but to no avail.[70] For his part, Charles replied that the, "queen has come of her own will and may freely return if she wishes. But if she prefers to remain here, she is my sister and I refuse to expel her." Charles went on to refuse to return the lands in Aquitaine to Edward, resulting in a provisional agreement under which Edward resumed administration of the remaining English territories in early 1326 whilst France continued to occupy the rest.[71]

Meanwhile, the messages brought back by Edward's agent Walter de Stapledon, Bishop of Exeter and others grew steadily worse: Isabella had publicly snubbed Stapledon; Edward's political enemies were gathering at the French court, and threatening his emissaries; Isabella was dressed as a widow, claiming that Hugh Despenser had destroyed her marriage with Edward; Isabella was assembling a court-in-exile, including Edmund of Kent and John of Brittany, Earl of Richmond.[70] By this stage Isabella had begun a romantic relationship with the English exile Roger Mortimer.

Roger Mortimer, 1325–1326

Isabella landing in England with her son, the future Edward III in 1326

Roger Mortimer of Wigmore was a powerful Marcher lord, married to the wealthy heiress Joan de Geneville, and the father of twelve children. Mortimer had been imprisoned in the Tower of London in 1322 following his capture by Edward during the Despenser wars. Mortimer's uncle, Roger Mortimer de Chirk finally died in prison, but Mortimer managed to escape the Tower in August 1323, making a hole in the stone wall of his cell and then escaping onto the roof, before using rope ladders provided by an accomplice to get down to the River Thames, across the river and then on eventually to safety in France.[72] Victorian writers suggested that, given later events, Isabella might have helped Mortimer escape and some historians continue to argue that their relationship had already begun at this point, although most believe that there is no hard evidence for their having had a substantial relationship before meeting in Paris.[73]

Isabella was reintroduced to Mortimer in Paris by her cousin, Joan, Countess of Hainault, who appears to have approached Isabella suggesting a marital alliance between their two families, marrying Prince Edward to Joan's daughter, Philippa.[74] Mortimer and Isabella began a passionate relationship from December 1325 onwards; Isabella was taking a huge risk in doing so – female infidelity was a very serious offence in medieval Europe, as shown during the Tour de Nesle Affair – both Isabella's former French sisters-in-law had died by 1326 as a result of their imprisonment for exactly this offence.[75] Isabella's motivation has been the subject of discussion by historians; most agree that there was a strong sexual attraction between the two, that they shared an interest in the Arthurian legends and that they both enjoyed fine art and high living.[76] One historian has described their relationship as one of the "great romances of the Middle Ages".[77] They also shared a common enemy – the regime of Edward II and the Despensers.

Taking Prince Edward with them, Isabella and Mortimer left the French court in summer 1326 and travelled north to William I, Count of Hainaut. As Joan had suggested the previous year, Isabella betrothed Prince Edward to Philippa, the daughter of the Count, in exchange for a substantial dowry.[78] She then used this money plus an earlier loan from Charles[79] to raise a mercenary army, scouring Brabant for men, which were added to a small force of Hainaut troops.[80] William also provided eight men of war ships and various smaller vessels as part of the marriage arrangements. Although Edward was now fearing an invasion, secrecy remained key, and Isabella convinced William to detain envoys from Edward.[80] Isabella also appears to have made a secret agreement with the Scots for the duration of the forthcoming campaign.[81] On 22 September, Isabella, Mortimer and their modest force set sail for England.[82]

Seizure of power, 1326

Isabella (left) directing the Siege of Bristol in October 1326

Having evaded Edward's fleet, which had been sent to intercept them,[83] Isabella and Mortimer landed at Orwell on the east coast of England on 24 September with a small force; estimates of Isabella's army vary from between 300 and around 2,000 soldiers, with 1,500 being a popular middle figure.[84] After a short period of confusion during which they attempted to work out where they had actually landed, Isabella moved quickly inland, dressed in her widow's clothes.[85] The local levies mobilised to stop them immediately changed sides, and by the following day Isabella was in Bury St Edmunds and shortly afterwards had swept inland to Cambridge.[83]Thomas, Earl of Norfolk, joined Isabella's forces and Henry of Lancaster – the brother of the late Thomas, and Isabella's uncle – also announced he was joining Isabella's faction, marching south to join her.[83]

By the 27th, word of the invasion had reached the King and the Despensers in London.[83] Edward issued orders to local sheriffs to mobilise opposition to Isabella and Mortimer, but London itself was becoming unsafe because of local unrest and Edward made plans to leave.[83] Isabella struck west again, reaching Oxford on 2 October where she was "greeted as a saviour" – Adam Orleton, the bishop of Hereford, emerged from hiding to give a lecture to the university on the evils of the Despensers.[86] Edward fled London on the same day, heading west toward Wales.[87] Isabella and Mortimer now had an effective alliance with the Lancastrian opposition to Edward, bringing all of his opponents into a single coalition.[88]

Isabella and Edward's campaign in 1326.[89]

Isabella now marched south towards London, pausing at Dunstable, outside the city on 7 October.[90] London was now in the hands of the mobs, although broadly allied to Isabella. Bishop Stapledon failed to realise the extent to which royal power had collapsed in the capital and tried to intervene militarily to protect his property against rioters; a hated figure locally, he was promptly attacked and killed – his head was later sent to Isabella by her local supporters.[91] Edward, meanwhile, was still fleeing west, reaching Gloucester by the 9th. Isabella responded by marching swiftly west herself in an attempt to cut him off, reaching Gloucester a week after Edward, who slipped across the border into Wales the same day.[92]

Hugh de Despenser the elder continued to hold Bristol against Isabella and Mortimer, who placed it under siege between 18–26 October; when it fell, Isabella was able to recover her daughters Eleanor and Joan, who had been kept in the Despenser's custody.[93] By now desperate and increasingly deserted by their court, Edward and Hugh Despenser the younger attempted to sail to Lundy, a small island just off the Devon coast, but the weather was against them and after several days they were forced to land back in Wales.[94] With Bristol secure, Isabella moved her base of operations up to the border town of Hereford, from where she ordered Henry of Lancaster to locate and arrest her husband.[95] After a fortnight of evading Isabella's forces in South Wales, Edward and Hugh were finally caught and arrested near Llantrisant on 16 November.

Hugh Despenser the younger and Edmund Fitzalan brought before Isabella for trial in 1326; the pair were gruesomely executed

The retribution began immediately. Hugh Despenser the elder had been captured at Bristol, and despite some attempts by Isabella to protect him, was promptly executed by his Lancastrian enemies – his body was hacked to pieces and fed to the local dogs.[96] The remainder of the former regime were brought to Isabella. Edmund Fitzalan, a key supporter of Edward II and who had received many of Mortimer's confiscated lands in 1322, was executed on 17 November. Hugh Despenser the younger was sentenced to be brutally executed on 24 November, and a huge crowd gathered in anticipation at seeing him die. They dragged him from his horse, stripped him, and scrawled Biblical verses against corruption and arrogance on his skin. He was then dragged into the city, presented to Queen Isabella, Roger Mortimer, and the Lancastrians. Despenser was then condemned to hang as a thief, be castrated, and then to be drawn and quartered as a traitor, his quarters to be dispersed throughout England. Simon of Reading, one of the Despensers' supporters, was hanged next to him, on charges of insulting Isabella.[97] Once the core of the Despenser regime had been executed, Isabella and Mortimer began to show restraint. Lesser nobles were pardoned and the clerks at the heart of the government, mostly appointed by the Despensers and Stapleton, were confirmed in office.[98] All that was left now was the question of Edward II, still officially Isabella's legal husband and lawful king.[99]

Death of Edward, 1327

An imaginative medieval interpretation of Edward's arrest by Isabella, seen watching from the right.

As an interim measure, Edward II was held in the custody of Henry of Lancaster, who surrendered Edward's Great Seal to Isabella.[100] The situation remained tense, however; Isabella was clearly concerned about Edward's supporters staging a counter-coup, and in November she seized the Tower of London, appointed one of her supporters as mayor and convened a council of nobles and churchmen in Wallingford to discuss the fate of Edward.[101] The council concluded that Edward would be legally deposed and placed under house arrest for the rest of his life. This was then confirmed at the next parliament, dominated by Isabella and Mortimer's followers. The session was held in January 1327, with Isabella's case being led by her supporter Adam Orleton, Bishop of Hereford. Isabella's son, Prince Edward, was confirmed as Edward III, with his mother appointed regent.[102] Isabella's position was still precarious, as the legal basis for deposing Edward was doubtful and many lawyers of the day maintained that Edward was still the rightful king, regardless of the declaration of the Parliament. The situation could be reversed at any moment and Edward was known to be a vengeful ruler.

Edward II's subsequent fate, and Isabella's role in it, remains hotly contested by historians. The minimally agreed version of events is that Isabella and Mortimer had Edward moved from Kenilworth Castle in the Midlands to the safer location of Berkeley Castle in the Welsh borders, where he was put into the custody of Lord Berkeley. On 23 September, Isabella and Edward III were informed by messenger that Edward had died whilst imprisoned at the castle, because of a "fatal accident". Edward's body was apparently buried at Gloucester Cathedral, with his heart being given in a casket to Isabella. After the funeral, there were rumours for many years that Edward had survived and was really alive somewhere in Europe, some of which were captured in the famous Fieschi Letter written in the 1340s, although no concrete evidence ever emerged to support the allegations. There are, however, various historical interpretations of the events surrounding this basic sequence of events.

Berkeley Castle, where Edward II was popularly said to have been murdered on the orders of Isabella and Mortimer; some current scholarship disputes this interpretation.

According to legend, Isabella and Mortimer famously plotted to murder Edward in such a way as not to draw blame on themselves, sending a famous order (in Latin: Eduardum occidere nolite timere bonum est) which, depending on where the comma was inserted, could mean either "Do not be afraid to kill Edward; it is good" or "Do not kill Edward; it is good to fear". In actuality, there is little evidence of anyone deciding to have Edward assassinated, and none whatsoever of the note having been written. Similarly, accounts of Edward being killed with a red-hot poker have no strong contemporary sources to support them. The conventional 20th-century view has been that Edward did die at Berkeley Castle, either murdered on Isabella's orders or of ill-health brought on by his captivity, and that subsequent accounts of his survival were simply rumours, similar to those that surrounded Joan of Arc and other near contemporaries after their deaths.

Three recent historians, however, have offered an alternative interpretation of events. Paul Doherty, drawing extensively on the Fieschi Letter of the 1340s, has argued that Edward in fact escaped from Berkeley Castle with the help of William Ockle, a knight whom Doherty argues subsequently pretended to be Edward in disguise around Europe, using the name "William the Welshman" to draw attention away from the real Edward himself. In this interpretation, a look-alike was buried at Gloucester.[103]Ian Mortimer, focusing more on contemporary documents from 1327 itself, argues that Roger de Mortimer engineered a fake "escape" for Edward from Berkeley Castle; after this Edward was kept in Ireland, believing he was really evading Mortimer, before finally finding himself free, but politically unwelcome, after the fall of Isabella and Mortimer. In this version, Edward makes his way to Europe, before subsequently being buried at Gloucester.[104] Finally, Alison Weir, again drawing on the Fieschi Letter, has recently argued that Edward II escaped his captors, killing one in the process, and lived as a hermit for many years; in this interpretation, the body in Gloucester Cathedral is of Edward's dead captor. In all of these versions, it is argued that it suited Isabella and Mortimer to publicly claim that Edward was dead, even if they were aware of the truth. Other historians, however, including David Carpenter, have criticised the methodology behind this revisionist approach and disagree with the conclusions.[105]

Later years

Isabella and Mortimer ruled together for four years, with Isabella's period as regent marked by the acquisition of huge sums of money and land. When their political alliance with the Lancastrians began to disintegrate, Isabella continued to support Mortimer, her lover. Isabella fell from power when her son, Edward III deposed Mortimer in a coup, taking back royal authority for himself. Unlike Mortimer, Isabella survived the transition of power, however, remaining a wealthy and influential member of the English court, albeit never returning directly to active politics.[106]

As regent, 1326–1330

15th-century manuscript illustration that depicts Isabella and allegedly Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March at Hereford; the execution of Hugh Despenser the younger can be seen in the background.

Isabella's reign as regent lasted only four years, before the fragile political alliance that had brought her and Mortimer to power disintegrated. 1328 saw the marriage of Isabella's son, Edward III to Philippa of Hainault, as agreed before the invasion of 1326; the lavish ceremony was held in London to popular acclaim.[107] Isabella and Mortimer had already begun a trend that continued over the next few years, in starting to accumulate huge wealth. With her lands restored to her, Isabella was already exceptionally rich, but she began to accumulate yet more. Within the first few weeks, Isabella had granted herself almost £12,000;[108] finding that Edward's royal treasury contained £60,000, a rapid period of celebratory spending then ensued.[109] Isabella soon awarded herself another £20,000, allegedly to pay off foreign debts.[110] At Prince Edward's coronation, Isabella then extended her land holdings from a value of £4,400 each year to the huge sum of £13,333, making her one of the largest landowners in the kingdom.[111] Isabella also refused to hand over her dower lands to Philippa after her marriage to Edward III, in contravention of usual custom.[112] Isabella's lavish lifestyle matched her new incomes.[113] Mortimer, as her lover and effective first minister, after a restrained beginning, also began to accumulate lands and titles at a tremendous rate, particularly in the Marcher territories.[114]

The new regime also faced some key foreign policy dilemmas, which Isabella approached from a realist perspective.[115] The first of these was the situation in Scotland, where Edward II's unsuccessful policies had left an unfinished, tremendously expensive war. Isabella was committed to bringing this issue to a conclusion by diplomatic means. Edward III initially opposed this policy, before eventually relenting,[116] leading to the Treaty of Northampton. Under this treaty, Isabella's daughter Joan would marry David Bruce (heir apparent to the Scottish throne) and Edward III would renounce any claims on Scottish lands, in exchange for the promise of Scottish military aid against any enemy except the French, and £20,000 in compensation for the raids across northern England. No compensation would be given to those earls who had lost their Scottish estates, and the compensation would be taken by Isabella.[117] Although strategically successful and, historically at least, "a successful piece of policy making",[118] Isabella's Scottish policy was by no means popular and contributed to the general sense of discontent with the regime. Secondly, the Gascon situation, still unresolved from Edward II's reign, also posed an issue. Isabella reopened negotiations in Paris, resulting in a peace treaty under which the bulk of Gascony, minus the Agenais, would be returned to England in exchange for a 50,000 mark penalty.[119] The treaty was not popular in England because of the Agenais clause.[115]

Henry of Lancaster was amongst the first to break with Isabella and Mortimer. By 1327 Lancaster was irritated by Mortimer's behaviour and Isabella responded by beginning to sideline him from her government.[120] Lancaster was furious over the passing of the Treaty of Northampton, and refused to attend court,[121] mobilising support amongst the commoners of London.[122] Isabella responded to the problems by undertaking a wide reform of royal administration, local law enforcement.[123] In a move guaranteed to appeal to domestic opinion, Isabella also decided to pursue Edward III's claim on the French throne, sending her advisers to France to demand official recognition of his claim.[123] The French nobility were unimpressed and, since Isabella lacked the funds to begin any military campaign, she began to court the opinion of France's neighbours, including proposing the marriage of her son John to the Castilian royal family.[124]

By the end of 1328 the situation had descended into near civil war once again, with Lancaster mobilising his army against Isabella and Mortimer.[125] In January 1329 Isabella's forces under Mortimer's command took Lancaster's stronghold of Leicester, followed by Bedford; Isabella – wearing armour, and mounted on a warhorse – and Edward III marched rapidly north, resulting in Lancaster's surrender. He escaped death but was subjected to a colossal fine, effectively crippling his power.[126] Isabella was merciful to those who had aligned themselves with him, although some – such as her old supporter Henry de Beaumont, whose family had split from Isabella over the peace with Scotland, which had lost them huge land holdings in Scotland[127] – fled to France.[128]

Despite Lancaster's defeat, however, discontent continued to grow. Edmund of Kent had sided with Isabella in 1326, but had since begun to question his decision and was edging back towards Edward II, his half-brother. Edmund of Kent was in conversations with other senior nobles questioning Isabella's rule, including Henry de Beaumont and Isabella de Vesci. Edmund was finally involved in a conspiracy in 1330, allegedly to restore Edward II, who, he claimed, was still alive: Isabella and Mortimer broke up the conspiracy, arresting Edmund and other supporters – including Simon Mepeham, Archbishop of Canterbury.[129] Edmund may have expected a pardon, possibly from Edward III, but Isabella was insistent on his execution.[130] The execution itself was a fiasco after the executioner refused to attend and Edmund of Kent had to be killed by a local dung-collector, who had been himself sentenced to death and was pardoned as a bribe to undertake the beheading.[131] Isabella de Vesci escaped punishment, despite having been closely involved in the plot.

Mortimer's fall from power, 1330

By mid-1330, Isabella and Mortimer's regime was increasingly insecure, and Isabella's son, Edward III, was growing frustrated at Mortimer's grip on power. Various historians, with different levels of confidence, have also suggested that in late 1329 Isabella became pregnant. A child of Mortimer's with royal blood would have proved both politically inconvenient for Isabella, and challenging to Edward's own position.[132]

Berkhamsted Castle, where Isabella was initially held after Mortimer and her fall from power in 1330.

Edward quietly assembled a body of support from the Church and selected nobles,[133] whilst Isabella and Mortimer moved into Nottingham Castle for safety, surrounding themselves with loyal troops.[134] In the autumn, Mortimer was investigating another plot against him, when he challenged a young noble, Montague, during an interrogation. Mortimer declared that his word had priority over the king's, an alarming statement that Montague reported back to Edward.[135] Edward was convinced that this was the moment to act, and on 19 October, Montague led a force of twenty three armed men into the castle by a secret tunnel. Up in the keep, Isabella, Mortimer and other council members were discussing how to arrest Montague, when Montague and his men appeared.[136] Fighting broke out on the stairs and Mortimer was overwhelmed in his chamber. Isabella threw herself at Edward's feet, famously crying "Fair son, have pity on gentle Mortimer!"[136] Lancastrian troops rapidly took the rest of the castle, leaving Edward in control of his own government for the first time.

Parliament was convened the next month, where Mortimer was put on trial for treason. Isabella was portrayed as an innocent victim during the proceedings,[137] and no mention of her sexual relationship with Mortimer was made public.[138] Isabella's lover was executed at Tyburn, but Edward III showed leniency and he was not quartered or disembowelled.[139]

In retirement, 1330–1358

Castle Rising; bought by Isabella in 1327, it formed her home during her later years.

After the coup, Isabella was initially transferred to Berkhamsted Castle,[140] and then held under house arrest at Windsor Castle until 1332, when she then moved back to her own Castle Rising in Norfolk.[141]Agnes Strickland, a Victorian historian, argued that Isabella suffered from occasional fits of madness during this period but modern interpretations suggest, at worst, a nervous breakdown following the death of her lover.[141] Isabella remained extremely wealthy; despite being required to surrender most of her lands after losing power,[142] in 1331 she was reassigned a yearly income of £3000, which increased to £4000 by 1337.[141] She lived an expensive lifestyle in Norfolk, including minstrels, huntsmen, grooms and other luxuries,[143] and was soon travelling again around England. In 1342, there were suggestions that she might travel to Paris to take part in peace negotiations, but eventually this plan was quashed.[144] She was also appointed to negotiate with France in 1348 and was involved in the negotiations with Charles II of Navarre in 1358.[145]

As the years went by, Isabella became very close to her daughter Joan, especially after Joan left her unfaithful husband, King David II of Scotland.[146] Joan also nursed her just before she died. She doted on her grandchildren, including Edward, the Black Prince. She became increasingly interested in religion as she grew older, visiting a number of shrines.[147] She remained, however, a gregarious member of the court, receiving constant visitors; amongst her particular friends appear to have been Roger Mortimer's daughter Agnes Mortimer, Countess of Pembroke, and Roger Mortimer's grandson, also called Roger Mortimer, whom Edward III restored to the Earldom of March.[148] King Edward and his children often visited her as well.[145] She remained interested in Arthurian legends and jewellery; in 1358 she appeared at the St George's Day celebrations at Windsor wearing a dress made of silk, silver, 300 rubies, 1800 pearls and a circlet of gold.[143] She may also have developed an interest in astrology or geometry towards the end of her life, receiving various presents relating to these disciplines.[149]

Isabella took the nun's habit of the Poor Clares before she died on 22 August 1358 at Hertford Castle, and her body was returned to London for burial at the Franciscan church at Newgate, in a service overseen by Archbishop Simon Islip.[150] She was buried in the mantle she had worn at her wedding and at her request, Edward's heart, placed into a casket thirty years before, was interred with her. Isabella left the bulk of her property, including Castle Rising, to her favourite grandson, the Black Prince, with some personal effects being granted to her daughter Joan.[151]

Cultural depictions

Literature and theatre

Queen Isabella appeared with a major role in Christopher Marlowe's play Edward II (c. 1592) and thereafter has been frequently used as a character in plays, books, and films, often portrayed as beautiful but manipulative or wicked. Thomas Gray, the 18th-century poet, combined Marlowe's depiction of Isabella with William Shakespeare's description of Margaret of Anjou (the wife of Henry VI) as the "She-Wolf of France", to produce the anti-French poem The Bard (1757), in which Isabella rips apart the bowels of Edward II with her "unrelenting fangs".[152] The "She-Wolf" epithet stuck, and Bertolt Brecht re-used it in The Life of Edward II of England (1923).[152]

Film

In Derek Jarman's film Edward II (1991), based on Marlowe's play, Isabella is portrayed (by actress Tilda Swinton) as a "femme fatale" whose thwarted love for Edward causes her to turn against him and steal his throne. In contrast to the negative depictions, Mel Gibson's film Braveheart (1995) portrays Isabella (played by the French actress Sophie Marceau) more sympathetically. In the film, an adult Isabella is fictionally depicted as having a romantic affair with the Scottish hero William Wallace. However, in reality, she was nine years old at the time of Wallace's death.[153] Additionally, Wallace is incorrectly suggested to be the father of her son, Edward III, despite Wallace's death being many years before Edward's birth.[154]

Issue

Edward and Isabella had four children, and she suffered at least one miscarriage. Their itineraries demonstrate that they were together 9 months prior to the births of all four surviving offspring. Their children were:[155]

Edward III, born 1312

John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall, born 1316

Eleanor of Woodstock, born 1318, married Reinoud II of Guelders

Joan of the Tower, born 1321, married David II of Scotland

Arms

|

|

Ancestry

.mw-parser-output table.ahnentafel{border-collapse:separate;border-spacing:0;line-height:130%}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel tr{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel-t{border-top:#000 solid 1px;border-left:#000 solid 1px}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel-b{border-bottom:#000 solid 1px;border-left:#000 solid 1px}

| Ancestors of Isabella of France | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Isabella is descended from Gytha of Wessex through King Andrew II of Hungary and thus brought the bloodline of the last Anglo-Saxon King of England, Harold Godwinson, back into the English Royal family.[165]

See also

- Geoffrey the Baker

- Hundred Years' War

- Vita Edwardi Secundi

Notes

^ Weir 1999, pg. 90.

^ Castor page 227

^ See Weir 2006, pp8-9.

^ Weir 2006, p.11.

^ Jones and McKitterick, p.394.

^ Weir 2006, p.12.

^ Weir 2006, p.14.

^ ab Weir 2006, p.13.

^ Weir 2006, p.13-4.

^ ab Weir 2006, p.25.

^ Costain, p.82; Weir 2006, p.12.

^ Weir 2006, p.26.

^ Weir 2006, p.243.

^ Mortimer, 2004, p.36.

^ For a summary of this period, see Weir 2006, chapters 2–6; Mortimer, 2006, chapter 1; Doherty, chapters 1–3.

^ Weir 2006, p.39.

^ ab Weir 2006, p.37.

^ ab Doherty, p.37.

^ Doherty, p.38.

^ Doherty, p.46.

^ ab Doherty, p.47.

^ Hilton, Lisa (2008). Queens Consort, England's Medieval Queens. Great Britain: Weidenfeld & Nichelson. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-7538-2611-9..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Doherty, pp47-8.

^ ab Doherty, p.49.

^ ab Weir 2006, p.58.

^ Weir 2006, p.63.

^ Doherty, p.51.

^ Doherty, p.54.

^ Weir 2006, p.68.

^ Doherty, p.56.

^ ab Weir 2006, p.92.

^ Weir 2006, p.92, 99.

^ Doherty, p.60.

^ ab Doherty, p.61.

^ Doherty, pp.60–1.

^ Doherty, pp.61–2.

^ Doherty, p.62.

^ ab Doherty, p.64.

^ Weir 2006, p.120.

^ Doherty, p.65.

^ Doherty, p.66.

^ Doherty, p.67.

^ Weir 2006, p.132.

^ Doherty, p.67; Weir 2006, p.132.

^ Doherty, p.70.

^ Doherty, p.70-1; Weir 2006, p.133.

^ ab Doherty, p.71.

^ Doherty, pp72-3.

^ Weir 2006, p.138.

^ Doherty, pp74-5.

^ Doherty, p.73.

^ Weir 2006, p.143.

^ Weir 2006, p.144.

^ Weir 2006, p.149.

^ Doherty, p.75.

^ Doherty, pp.76–7.

^ abc Doherty, p.77.

^ ab Doherty, p.78.

^ ab Doherty, p.79.

^ Doherty, p.80.

^ For a summary of this period, see Weir 2006, chapters 6–8; Doherty, chapter 4; Mortimer, 2006, chapter 2; Mortimer, 2004, chapters 9-11.

^ Ainsworth, p.3.

^ ab Holmes, p.16.

^ Neillands, p.30.

^ Neillands, p.31.

^ Holmes, p.16; Kibler, p.201.

^ Kibler, p.314.

^ Doherty, pp.80–1.

^ Sumption, p.97.

^ abc Doherty, p.81.

^ Kibler, p.314; Sumption, p.98.

^ Weir 2006, p.153.

^ Weir 2006, p.154; see Mortimer, 2004 pp128-9 for the alternative perspective.

^ Weir 2006, p.194.

^ A point born out by Mortimer, 2004, p.140.

^ Weir 2006, p.197.

^ Mortimer, 2004, p.141.

^ Kibler, p.477.

^ Lord, p.47.

^ ab Weir 2006, p.221.

^ Weir 2006, p.222.

^ Weir 2006, p.223.

^ abcde Doherty, p.90.

^ Mortimer, 2004, p.148-9.

^ Weir 2006, p.225.

^ Weir 2006, p.227.

^ Doherty, p.91.

^ Doherty, p.92

^ From Weir 2006, chapter 8; Mortimer, 2006, chapter 2; and Myers's map of Medieval English transport systems, p.270.

^ Weir 2006, p.228.

^ Weir 2006, p.228-9; p.232.

^ Weir 2006, p.232.

^ Doherty, p.92; Weir 2006, pp233-4.

^ Weir 2006, p.233.

^ Weir 2006, p.236.

^ Doherty, p.93.

^ Mortimer The Greatest Traitor, pp. 159–162.

^ Doherty, p.107.

^ Weir 2006, p.242.

^ Doherty, p. 108.

^ Doherty, p. 109.

^ Doherty, pp 114–15.

^ Doherty, pp 213–15.

^ Mortimer, 2004, pp 244–264; Mortimer, 2006, appendix 2.

^ See Carpenter 2007a, Carpenter 2007b.

^ For a summary of this period, see Weir 2006, chapter 11; Doherty, chapter 8; Mortimer, 2006, chapter 4.

^ Doherty, p.142.

^ Weir 2006, p.245.

^ Weir 2006, p.248.

^ Weir 2006, p.249.

^ Weir 2006, p.259.

^ Weir 2006, p.303.

^ Weir 2006, p.258.

^ Doherty, p.156.

^ ab Weir 2006, p.261.

^ Weir 2006, p.304.

^ Weir 2006, p.305, p.313.

^ Weir 2006, p.306.

^ Weir 2006, p.261; Neillands, p.32.

^ Weir 2006, p.307.

^ Weir 2006, p.314.

^ Weir 2006, p.315.

^ ab Weir 2006, p.309.

^ Weir 2006, p.310.

^ Weir 2006, p.322.

^ Weir 2006, p.322; Mortimer, 2004, p.218.

^ Doherty, p.149.

^ Weir 2006, p.333.

^ Doherty, p.151.

^ Doherty, p.152.

^ Doherty, p.153.

^ Weir 2006, p.326, is relatively cautious in this assertion; Mortimer, 2004 pp221-3 is more confident.

^ Doherty, pp158-9.

^ Doherty, p.159.

^ Doherty, p.160.

^ ab Doherty, p.161.

^ Doherty, p.162.

^ Doherty, p.172.

^ Doherty, p.163.

^ Weir 2006, p347.

^ abc Doherty, p.173.

^ Weir 2006, p.353.

^ ab Doherty, p.176.

^ Doherty, p.174.

^ ab Mortimer, Ian (2008). The Perfect King The Life of Edward III, Father of the English Nation. Vintage. p. 332.

^ Doherty, p.175.

^ Doherty, pp175-6.

^ Doherty, p.177.

^ Weir 2006, p.371.

^ Weir 2006, p.374.

^ Weir 2006, p.373.

^ ab Weir 2006, p. 2.

^ "The lying art of historical fiction". Guardian News. 6 August 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

^ Ewan, pp. 1219–21.

^ Haines, Roy Martin (2003). King Edward II: His Life, his Reign and its Aftermath, 1284–1330. Montreal, Canada and Kingston, Canada: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-7735-3157-4.

^ Boutell, p.133.

^ Willement, Thomas. Regal heraldry; the armorial insignia of the Kings and Queens of England, from coeval authorities, London: W. Wilson; Rodwell and Martin. 1821. pg 14, 25. Regal Heraldry

^ Pinches, John Harvey; Pinches, Rosemary (1974), The Royal Heraldry of England, Heraldry Today, Slough, Buckinghamshire: Hollen Street Press,

ISBN 0-900455-25-X

^ abcd Anselme 1726, pp. 87–88

^ abcdef Anselme 1726, pp. 381–382

^ abcd Anselme 1726, pp. 83–85

^ abcd Evergates, Theodore (2011). Aristocratic Women in Medieval France. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 80.

^ abcd Anselme 1726, pp. 81–82

^ ab Nicholson, Helen J. (2004). The Crusades. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 113. ISBN 978-0313326851.

^ abc Weir 1999, p. 90.

^ ab Evergates 2011, p. 247

Sources

- Ainsworth, Peter. (2006) Representing Royalty: Kings, Queens and Captains in Some Early Fifteenth Century Manuscripts of Froissart's Chroniques. in Kooper (ed) 2006.

Anselme de Sainte-Marie, Père (1726). Histoire généalogique et chronologique de la maison royale de France [Genealogical and chronological history of the royal house of France] (in French). 1 (3rd ed.). Paris: La compagnie des libraires.

- Boutell, Charles. (1863) A Manual of Heraldry, Historical and Popular. London: Winsor & Newton.

Carpenter, David. (2007a) "What Happened to Edward II?" London Review of Books. Vol. 29, No. 11. 7 June 2007.- Carpenter, David. (2007b) "Dead or Alive." London Review of Books. Vol. 29, No. 15. 2 August 2007.

Castor, Helen. (2011) She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth, Faber and Faber .

ISBN 0571237061

Doherty, P.C. (2003) Isabella and the Strange Death of Edward II. London: Robinson.

ISBN 1-84119-843-9.- Ewan, Elizabeth. "Braveheart." American Historical Review. Vol. 100, No. 4. October 1995.

- Given-Wilson, Chris. (ed) (2002) Fourteenth Century England. Prestwich: Woodbridge.

- Holmes, George. (2000) Europe, Hierarchy and Revolt, 1320–1450, 2nd edition. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Kibler, William W. (1995) Medieval France: an Encyclopedia. London: Routledge.

- Kooper, Erik (ed). (2006) The Medieval Chronicle IV. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Lord, Carla. (2002) Queen Isabella at the Court of France. in Given-Wilson (ed) (2002).

Mortimer, Ian. (2004) The Greatest Traitor: The Life of Sir Roger Mortimer, Ruler of England 1327–1330. London: Pimlico Press.- Mortimer, Ian. (2006) The Perfect King: The Life of Edward III, Father of the English Nation. London: Vintage Press.

ISBN 978-0-09-952709-1. - Myers, A. R. (1978) England in the Late Middle Ages. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Neillands, Robin. (2001) The Hundred Years War. London: Routledge.

- Sumption, Jonathan. (1999) The Hundred Years War: Trial by Battle. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania University Press.

Weir, Alison. (1999) Britain's Royal Family: A Complete Genealogy. London: The Bodley Head.- Weir, Alison. (2006) Queen Isabella: She-Wolf of France, Queen of England. London: Pimlico Books.

ISBN 978-0-7126-4194-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isabella of France, Queen of England. |

- Heidi Murphy Isabella of France (1295–1358), Britannia biographical series

English royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

Vacant Title last held by Margaret of France | Queen consort of England Lady of Ireland 25 January 1308 – 25 January 1327 | Vacant Title next held by Philippa of Hainault |