Iranian Armenians

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Data differs between: 70,000–90,000,[1] 120,000[2] 150,000,[3] up to 200,000[4] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

Tehran, Tabriz, Esfahan (New Julfa), West Azerbaijan Province, Peria, Bourvari | |

| Languages | |

Armenian, Persian | |

| Religion | |

Armenian Apostolic, Armenian Catholic and Evangelical |

| Part of a series on |

| Armenians |

|---|

|

Armenian culture |

Architecture · Art Cuisine · Dance · Dress Literature · Music · History |

By country or region |

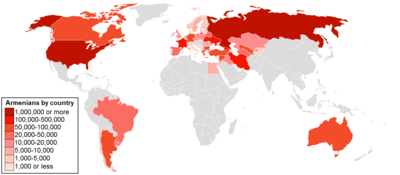

Armenia · Artsakh See also Nagorno-Karabakh Armenian diaspora Russia · France · India United States · Iran · Georgia Azerbaijan · Argentina · Brazil Lebanon · Syria · Ukraine Poland · Canada · Australia Turkey · Greece · Cyprus Egypt · Singapore |

Subgroups |

Hamshenis · Cherkesogai · Armeno-Tats · Lom people · Hayhurum |

Religion |

Armenian Apostolic · Armenian Catholic Evangelical · Brotherhood · |

Languages and dialects |

Armenian: Eastern · Western |

Persecution |

Genocide · Hamidian massacres Adana massacre · Anti-Armenianism Hidden Armenians |

Armenia Portal |

Iranian-Armenians (Armenian: իրանահայեր iranahayer) also known as Persian-Armenians (Armenian: պարսկահայեր parskahayer), are Iranians of Armenian ethnicity who may speak Armenian as their first language. Estimates of their number in Iran range from 70,000 to 200,000. Areas with a higher concentration of them include Tabriz, Tehran and Isfahan's Jolfa (Nor Jugha) quarter.

Armenians have lived for millenia in the territory that forms modern-day Iran. Several times in history Iran's northwestern regions were part of Armenia. Many of the oldest Armenian churches, monasteries, and chapels are located within modern-day Iran. Persian Armenia, which includes modern-day Armenian Republic was part of Qajar Iran up to 1828. Iran had one of the largest populations of Armenians in the world alongside neighboring Ottoman Empire until the beginning of the 20th century.

Armenians were influential and active in the modernization of Iran during the 19th and 20th centuries. After the Iranian Revolution, many Armenians emigrated to Armenian diasporic communities in North America and Western Europe. Today the Armenians are Iran's largest Christian religious minority.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Early modern to late modern era

1.2 Loss of Eastern Armenia

1.3 Twentieth century up to 1979

1.4 After the 1979 Revolution

2 Distribution

2.1 Azerbaijan

2.1.1 Tabriz

2.1.1.1 Notable Armenians from Tabriz

2.2 Central Iran

3 Culture and language

4 See also

5 References

6 Sources

7 External links

History

The Armenian St. Thaddeus Monastery, or "Kara Kelissa", West Azarbaijan province. Believed by some to have been first built in 66 AD by Saint Jude.

Since Antiquity there has always been much interaction between Ancient Armenia and Persia (Iran). The Armenian people are amongst the native ethnic groups of northwestern Iran (known as Iranian Azerbaijan), having millennia long recorded history there while the region (or parts of it) have had made up part of historical Armenia numerous times in history. These historical Armenian regions that nowadays include Iranian Azerbaijan are Nor Shirakan, Vaspurakan, and Paytakaran. Many of the oldest Armenian chapels, monasteries and churches in the world are located within this region of Iran.

On the Behistun inscription of 515 BC, Darius the Great indirectly confirmed that Urartu and Armenia are synonymous when describing his conquests. Armenia became a satrap of the Persian Empire for a long period of time. Regardless, relations between Armenians and Persians were cordial.

The cultural links between the Armenians and the Persians can be traced back to Zoroastrian times. Prior to the 3rd century AD, no other neighbor had as much influence on Armenian life and culture as Parthia. They shared many religious and cultural characteristics, and intermarriage among Parthian and Armenian nobility was common. For twelve more centuries, Armenia was under the direct or indirect rule of the Persians.[5] While much influenced

by Persian culture and religion, Armenia also retained its unique characteristics as a nation. Later, Armenian Christianity retained some

Zoroastrian vocabulary and ritual[citation needed]

In the 11th century, the Seljuk Turks drove thousands of Armenians to Iranian Azerbaijan, where some were sold as slaves and others worked as artisans and merchants. After the Mongol conquest of Iran in the 13th century many Armenian merchants and artists settled in Iran, in cities that were once part of historic Armenia such as Khoy, Maku, Maragheh, Urmia, and especially Tabriz.[6]

Early modern to late modern era

Although Armenians have a long history of interaction and settlement with Persia/Iran and within the modern-day borders of the nation, Iran's Armenian community emerged under the Safavids. In the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire and Safavid Iran divided Armenia. From the early 16th century, both Western Armenia and Eastern Armenia fell under Iranian Safavid rule.[7][8] Owing to the century long Turco-Iranian geo-political rivalry that would last in Western Asia, significant parts of the region were frequently fought over between the two rivalling empires. From the mid 16th century with the Peace of Amasya, and decisively from the first half of the 17th century with the Treaty of Zuhab until the first half of the 19th century,[9] Eastern Armenia was ruled by the successive Iranian Safavid, Afsharid and Qajar empires, while Western Armenia remained under Ottoman rule. From 1604 Abbas I of Iran implemented a "scorched earth" policy in the region to protect his north-western frontier against any invading Ottoman forces, a policy which involved a forced resettlement of masses of Armenians outside of their homelands.[10]

Shah Abbas relocated an estimated 500,000 Armenians from his Armenian lands, during the Ottoman-Safavid War of 1603-1618,[10] to an area of Isfahan called New Julfa and the villages surrounding Isfahan in the early 17th century, which was created to become an Armenian quarter. Iran quickly recognized the Armenians' dexterity in commerce. The community became active in the cultural and economic development of Iran.[11]

Bourvari (Armenian: Բուրւարի) is a collection of villages in Iran, between the city of Khomein (Markazi Province) and Aligoodarz (Lorestān Province). It was mainly populated by Armenians who were forcibly deported to the region by Shah Abbas of the Safavid Persian Empire during the same as part of Abbas's massive scorched earth resettlement policies within the empire.[12] The following villages populated by the Armenians in Bourvari were: Dehno, Khorzend, Farajabad, Bahmanabad and Sangesfid.

Loss of Eastern Armenia

From the late 18th century, Imperial Russia switched to a more aggressive geo-political stance towards its two neighbors and rivals to the south, namely Iran and the Ottoman Empire. As a result of the Treaty of Gulistan (1813), Qajar Iran was forced to irrevocably cede swaths of its territories in the Caucasus, comprising modern-day Eastern Georgia, Dagestan, and most of the Republic of Azerbaijan. By the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828), Qajar Iran had to cede the remainder of its Caucasian territories, comprising modern-day Armenia and the remaining part of the contemporary Azerbaijan Republic.[13] The ceding of what is modern-day Armenia (Eastern Armenia in general) in 1828 resulted in a large amount of Armenians falling now under the rule of the Russians. Iranian Armenia was thus supplanted by Russian Armenia.

The Treaty of Turkmenchay further stipulated that the Tsar had the right to encourage resettling of Armenians from Iran into newly established Russian Armenia.[14][15] This resulted in a large demographic shift; many of Iran's Armenians followed the call, while many Caucasian Muslims migrated to Iran proper.

Until the mid-fourteenth century, Armenians had constituted a majority in Eastern Armenia.[16]

At the close of the fourteenth century, after Timur's campaigns, Islam had become the dominant faith, and Armenians became a minority in Eastern Armenia.[16] In the wake of the Russian invasion of Iran and the subsequent loss of territories, Muslims (Persians, Turkics, and Kurds) constituted some 80% of the population of Iranian Armenia, whereas Christian Armenians constituted a minority of about 20%.[17]

After the Russian administration took hold of Iranian Armenia, the ethnic make-up shifted, and thus for the first time in more than four centuries, ethnic Armenians started to form a majority once again in one part of historic Armenia.[18] The new Russian administration encouraged the settling of ethnic Armenians from Iran proper and Ottoman Turkey. Some 35,000 Muslims of over 100,000 emigrated from the region, while some 57,000 Armenians from Iran proper and Turkey (see also; Russo-Turkish War of 1828-1829) arrived after 1828.[19] As a result, by 1832, the number of ethnic Armenians had matched that of the Muslims.[17] Anyhow, it would be only after the Crimean War and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, which brought another influx of Turkish Armenians, that ethnic Armenians once again established a solid majority in Eastern Armenia.[20] Nevertheless, the city of Erivan remained having a Muslim majority up to the twentieth century.[20] According to the traveller H. F. B. Lynch, the city was about 50% Armenian and 50% Muslim (Azerbaijanis and Persians) in the early 1890s.[21]

With these events of the first half of the 19th century, and the end of centuries of Iranian rule over Eastern Armenia, a new era had started for the Armenians within the newly established borders of Iran. The Armenians in the recently lost territories to the north of the Aras river, would go through a Russian dominated period, until 1991.

Twentieth century up to 1979

Iranian Armenian women in the Qajar era

Shoghagat Church in Tabriz

Vank Cathedral in the New Julfa district of Isfahan. One of the oldest of Iran's Armenian churches, built during the Safavid Persian Empire, 1655 - 1664.[22]

The Armenians played a significant role in the development of 20th-century Iran, regarding both its economical as well as its cultural configuration.[23] They were pioneers in photography, theater, and the film industry, and also played a very pivotal role in Iranian political affairs.[23][24]

The Revolution of 1905 in Russia had a major effect on northern Iran and, in 1906, Iranian liberals and revolutionaries, demanded a constitution in Iran. In 1909 the revolutionaries forced the crown to give up some of its powers. Yeprem Khan, an ethnic Armenian, was an important figure of the Persian Constitutional Revolution.[25]

Armenian Apostolic theologian Malachia Ormanian, in his 1911 book on the Armenian Church, estimated that some 83,400 Armenians lived in Persia, of whom 81,000 were followers of the Apostolic Church, while 2,400 were Armenian Catholics. The Armenian population was distributed in the following regions: 40,400 in Azerbaijan, 31,000 in and around Isfahan, 7,000 in Kurdistan and Lorestan, and 5,000 in Tehran.[26]

In 1914 there were 230,000 Armenians in Iran.[citation needed] During the Armenian genocide about 50,000 Armenians fled the Ottoman Empire and took refuge in Persia. As a result of the Persian Campaign in northern Iran during World War I the Ottomans massacred 80,000 Armenians and 30,000 fled to the Russian Empire. The community experienced a political rejuvenation with the arrival of the exiled Dashnak (ARF) leadership from Russian Armenia in mid-1921; approximately 10,000 Armenian ARF party leaders, intellectuals, fighters, and their families crossed the Aras River and took refuge in Qajar Iran.[24] This large influx of Armenians who were affiliated with the ARF also meant that the ARF would ensure its dominance over the other traditional Armenian parties of Persia, and by that the entire Iranian Armenian community, which was centered around the Armenian church.[24] Further immigrants and refugees from the Soviet Union numbering nearly 30,000 continued to increase the Armenian community until 1933. Thus by 1930 there were approximately 200,000 Armenians in Iran.[27][28]

The modernization efforts of Reza Shah (1924–1941) and Mohammad Reza Shah (1941–1979) gave the Armenians ample opportunities for advancement,[29] and Armenians gained important positions in the arts and sciences, economy and services sectors, mainly in Tehran, Tabriz, and Isfahan that became major centers for Armenians. From 1946-1949 about 20,000 Armenians left Iran for the Soviet Union and from 1962-1982 another 25,000 Armenians followed them to Soviet Armenia.[30] By 1979, in the dawn of the Islamic Revolution, an estimated 250,000 - 300,000 Armenians were living in Iran.[31][32][33]

Armenian churches, schools, cultural centers, sports clubs and associations flourished and Armenians had their own senator and member of parliament, 300 churches and 500 schools and libraries served the needs of the community.

Armenian presses published numerous books, journals, periodicals, and newspapers, the prominent one being the daily "Alik".

After the 1979 Revolution

St. Sarkis Cathedral in Tehran. One of Iran's Armenian churches, 1970[34]

Many Armenians served in the Iranian army, and many died in action during the Iran–Iraq War.[35]

Later Iranian governments have been much more accommodating and the Armenians continue to maintain their own schools, clubs, and churches. The fall of the Soviet Union, the common border with Armenia, and the Armeno-Iranian diplomatic and economic agreements have opened a new era for the Iranian Armenians. Iran remains one of Armenia's major trade partners, and the Iranian government has helped ease the hardships of Armenia caused by the blockade imposed by Azerbaijan and Turkey. This includes important consumer products, access to air travel, and energy sources (like petroleum and electricity). The remaining Armenian minority in the Islamic Republic of Iran is still the largest Christian community in the country, far ahead of Assyrians.[36]

The Armenians remain the most powerful religious minority in Iran. They are appointed two out of five seats in the Iranian Parliament (the most within the Religious minority branch) and are the only minority with official Observing Status in the Guardian and Expediency Discernment Councils. Half of Iran's Armenians live in the Tehran area, most notably in its suburbs of Narmak, Majidiyeh, Nadershah, etc. A quarter live in Isfahan, and the other quarter is concentrated in Northwestern Iran or Iranian Azerbaijan.[37][38][38][39][40]

Distribution

Azerbaijan

In 387 AD when the Sasanian Empire and the Byzantine Empire split Armenia, the historically Armenian areas of Nor Shirakan, Paytakaran, and the eastern half of Vaspurakan were ceded to the Persians, these territories comprise the western and northern regions of Azerbaijan. Following the Russo-Persian War (1826–28) about 40,000 Armenians left Azerbaijan and resettled in newly established Russian Armenia.

The area retained a large Armenian population until 1914 when World War I began the Azerbaijan was invaded by the Ottomans who slaughtered much of the local Armenian population. Prior to the Ottoman invasion there were about 150,000 Armenians in Azerbaijan, and 30,000 of them were in Tabriz. About 80,000 were massacred, 30,000 fled to Russian Armenia, and the other 10,000 fled the area of the modern West Azerbaijan Province and took refuge among the Armenians of Tabriz. After the war ended in 1918 the 10,000 refugees in Tabriz returned to their villages, but many resettled in Soviet Armenia from 1947 up until the early 80s. Currently, about 4,000 Armenians remain in the countryside of East Azerbaijan and about 2,000 remain in Tabriz living in the districts of Nowbar, Bazar, and Ahrab owning 4 churches, a school and a cemetery.

This is a list of previously or currently Armenian inhabited settlements:

Salmas (Salmast in Armenian) now in Salmas County in West Azerbaijan Province: Kohneshahr, Akhtekhaneh, Aslanik, Charik, Drishk, Qalasar, Qezeljeh, Haftvan, Khosrowabad, Goluzan, Sheitanabad, Payajuk, Karabulagh, Hodar, Malham, Saramolk, Sarna, Savera, Zivajik, Kojamish and Ula.

Urmia (Vormi/Urmia in Armenian) now in Urmia County in West Azerbaijan Province:

Urmia, Balanej, Badelbo, Surmanabad, Jamalabad, Gardabad, Ikiaghaj, Isalu, Karaguz, Nakhichevan Tepe, Reihanabad, Sepurghan, Karabagh, Adeh, Dizej Ala, Khan Babakhan, Kachilan, Shirabad, Charbakhsh, Chahar Gushan, Ballu, Darbarud, Kukia and Babarud.

Khoy (Her in Armenian) now in Khoy and Chaypareh (Avarayr Plain) counties in West Azerbaijan Province:

Khoy, Mahlazan, Ghris, Fanai, Dizeh, Qotur, Chors, Var and Saidabad.- Maku (Shavarshan/Artaz in Armenian) now in Maku and Chalderan counties in West Azerbaijan Province:

Maku, Qareh-Kelisa, Shaveran and Baron (Dzor Dzor).

Arasbaran (Paytakaran in Armenian) now in Kaleybar and Khoda Afarin counties in East Azerbaijan Province:

Vinaq, Ayenehlu, Garmanab, Lameh and Vayqan.

Tabriz (Tavriz/Tavrezh in Armenian) now in Tabriz County in East Azerbaijan Province:

Tabriz, Mujumbar, Sohrol, Aljamolk and Minavar.

Julfa (Jugha in Armenian):- Upper Darashamb, Middle Darashamb and Lower Darashamb.

- Maragheh

- Ardabil

Miandoab: Taqiabad

Tabriz

Traditionally, Tabriz was the main city in Iranian Azerbaijan where Armenian political life vibrated from the early modern (Safavid) era and on.[41] After the ceding of swaths of territories to Russia in the first quarter of the 19th century, the independent position of the Tabrizi Armenians was strengthened, as they gained immunities and concessions by Abbas Mirza.[42] The particular importance of the Tabrizi Armenians also grew with the transfer of the bishop's seat from St.Taddeus (or Qara Kelissa) near Salmas to Tabriz in 1845.[42] Tabriz has an Arajnordaran, three Armenian Churches (S. Sargis, Shoghakat, and S. Mariam), a chapel, a school, an Ararat Cultural Club and an Armenian cemetery.

Notable Armenians from Tabriz

.mw-parser-output div.columns-2 div.column{float:left;width:50%;min-width:300px}.mw-parser-output div.columns-3 div.column{float:left;width:33.3%;min-width:200px}.mw-parser-output div.columns-4 div.column{float:left;width:25%;min-width:150px}.mw-parser-output div.columns-5 div.column{float:left;width:20%;min-width:120px}

|

|

Central Iran

In 1604 and following years, during Ottoman-Persian War, about 500,000 Armenians forced to move from Nakhichevan, Vayots Dzor, Artashat, Yerevan, Armavir, Kotayk, Gegharkunik, Aragatsotn, Shirak, Lori, Tsolakert, Daroynk, and Kars to Central Iran as part of Shah Abbas I scorched earth policy. Many died crossing the Arax River, and those that survived the river crossing most likely perished while spending the winter in the mountains of Azarbaijan. About 200,000 Armenians were alive the following spring. 160,000 of them would resettle in central Iran and 40,000 of them would resettle in Farahabad in Mazandaran. The climate in the summer in Farahabad was unhealthy and large numbers of the inhabitants died of epidemics, particularly malaria. The surviving Armenians returned to their homes north of the Arax River. The Armenians that resettled in central Iran built hundreds of new villages. The Armenians of Julfa resettled along the Zayanderud and built the New Julfa quarter in Isfahan. Some also resettled in Hamadan, Qazvin and Shiraz. The non-Julfa Armenians that resettled in central Iran were resettled in the area that stretched from Qazvin and Hamadan in the north to Isfahan in the south. They built hundreds of villages in 12 rural clusters. Between 1722-1729 the Afghans invaded Iran and the Armenians of central Iran were subjugated, harassed, and heavily taxed. The Armenians were forced to provide the Afghan invaders with rations. From 1747-1762 Persia experienced a civil war following the assassination of Nader Shah Afshar in 1747. During the 18th century many Armenians were executed and abducted. As a result of these horrific years many 80% of the Armenian was lost, many fled for Russia, British India (Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Burma), British Malaya (Malaysia & Singapore), and for the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). In 1870 a famine ravaged Iran and 2 million people lost their lives. By 1914 there were only 80,000 Armenians in central Iran.

List of Armenian villages in central Iran:

Kharaqan (Gharaghan in Armenian) now in Zarandieh County in Markazi Province:

Upper Chanakhchi, Lar, Charhad and Lower Chanakhchi.

Hamadan: Hamadan and Sheverin.

Malayer: Anuch, Deh Chaneh and Qaleh Fattahieh.

Kazaz (Kiazaz in Armenian) now in Shazand County in Markazi Province:

Shazand, Abbasabad and Anbarteh.

Kamareh (Kiamara in Armenian) now in Khomeyn County in Markazi Province:

Lilian, Qurchibash, Chartagh, Davudabad, Kandha, Darreh Shur, Mazra, Saki, Kajarestan and Mazraeh Qasem.

Borborud (Bourvari in Armenian) now in Aligudarz County in Lorestan Province:

Shapurabad, Khorzand, Parmishan, Pahra, Farajabad, Sang-e Sefid, Bahramabad, Dehnow, Qareh Kahriz, Nasrabad, Goran, Jowz, Cherbas, Jahan Khosh and Anuj.

Japloq (Giapla in Armenian) now in Azna County in Lorestan Province and Shazand County in Markazi Province:

Azna, Ahmadabad, Perchestan, Kamian, Masoudabad, Abbasabad, Bagh Muri, Tokhmar and Sharafabad.- Faridan (Peria in Armenian) now in Faridan, Buin & Miandasht and Fereydunshahr counties in Isfahan Province:

Zarneh, Upper Khoygan, Nemagerd, Gharghan, Sangbaran, Hezar Jarib, Singerd, Lower Khoygan, Adegan, Hadan, Milagerd, Surshegan, Savaran, Chigan, Derakhtak, Punestan, Qaleh Khajeh, Aznavleh, Bijgerd, Khong, Moghandar, Nanadegan and Darreh Bid.

Karvan, now in Tiran & Karvan County in Isfahan Province- Lenjan and Alenjan, now in Lenjan, Falavarjan and Mobarakeh counties in Isfahan Province: Khansarak, Kelisan, Mehregan, Pelart, Semsan, Kaleh Masih, Garkan, Zudan, Barchan, Jushan, Bondart, Koruj, Zazeran, Kapashan and Mamad.

- Charmahal or Gandoman: now in Borujen, Kiar, Lordegan and Shahr-e Kord counties in Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari Province: Vastegan, Geshnigan, Shalamzar, Gandoman, Sirak, Boldaji, Mamura, Mamuka, Hajiabad and Ahmadabad, Livasian and Zorigan.

The settlements of Lenjan, Alenjan and Karvan were abandoned in the 18th century.

The other settlements depopulated in the middle of the 20th century due to emigration to New Julfa, Teheran or Soviet Armenia (in 1945 and later in 1967). Currently only 1 village (Zarneh) in Peria is totally, and 4 other villages (Upper Khoygan, Gharghan, Nemagerd and Sangbaran) in Peria and 1 village (Upper Chanakhchi) in Gharaghan are partially settled by Armenians.

Other than these settlements there is an Armenian village near Gorgan (Qoroq) which is settled by Armenians recently moved from Soviet territory.

Culture and language

In addition to having their own churches and clubs, Armenians of Iran are one of the few linguistic minorities in Iran with their own schools.[43]

The Armenian language used in Iran holds a unique position in the usage of Armenian in the world, as most Armenians in the Diaspora use Western Armenian. However, Iranian Armenians speak an Eastern Armenian dialect that is very close to that used in Armenia, Georgia, and Russia. Iranian Armenians speak this dialect due in part to the fact that in 1604 much of the Armenian population in the Lake Van area, which used the eastern dialect, was displaced and sent to Isfahan by Shah Abbas. This also allowed for an older version to be preserved which uses classical Armenian orthography known as "Mashtotsian orthography" and spelling, whereas almost all other Eastern Armenian users (especially in the former Soviet Union) have adopted the reformed Armenian orthography which was applied in Soviet Armenia in the 1920s and continues in the present Republic of Armenia. This makes the Armenian language used in Iran and in the Armenian-Iranian media and publications unique, applying elements of both major Armenian language branches (pronunciation, grammar and language structure of Eastern Armenian and the spelling system of Western Armenian).

See also

Armenia–Iran relations, Satrapy of Armenia, Battle of Avarayr, Persian Armenia, Marzpanate Armenia, Arsacid dynasty of Armenia, Armenians in the Persianate

Ethnic minorities in Iran, Christians in Iran

- List of Armenian churches in Iran

- Monasteries: Monastery of St. Thaddeus, Monastery of St. Stephen the Protomartyr

- Cathedrals: Holy Mother of God Cathedral, All Saviour's Cathedral, St. Sarkis Cathedral

- List of Iranian Armenians

- Media: Alik, Arax, Hooys

- Sports: Ararat Football Club, Ararat Basketball Club, Ararat Stadium, Pan-Armenian Games

- Politics: Armenian Revolutionary Federation in Iran

- Art: Lilihan carpets and rugs

References

^ Abrahamyan, Gayane (18 October 2010). "Armenia: Iranian-Armenians Struggle to Change Image as "Foreigners"". eurasianet.org. Open Society Institute.Iran, which borders Armenia to the south, is home to an estimated 70,000-90,000 ethnic Armenians...

.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Vardanyan, Tamara (21 June 2007). "Իրանահայ համայնք. ճամպրուկային տրամադրություններ [The Iranian-Armenian community]" (in Armenian). Noravank Foundation.Հայերի թիվը հասնում է մոտ 120.000-ի։

^ Semerdjian, Harout Harry (14 January 2013). "Christian Armenia and Islamic Iran: An unusual partnership explained". The Hill....the presence of a substantial Armenian community in Iran numbering 150,000.

^ Mirzoyan, Alla (2010). Armenia, the Regional Powers, and the West: Between History and Geopolitics. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 109. ISBN 9780230106352.Today, the Armenian community in Iran numbers around 200,000...

^ http://www.great-iran.com/PDFs/History/Different-files/Religious-Minorities-in-Iran.pdf

^ "Armenian Iran history". Home.wanadoo.nl. Archived from the original on 2012-03-24. Retrieved 2012-03-21.

^ Donald Rayfield. Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia Reaktion Books, 2013

ISBN 1780230702 p 165

^ Steven R. Ward. Immortal, Updated Edition: A Military History of Iran and Its Armed Forces Georgetown University Press, 8 jan. 2014

ISBN 1626160325 p 43

^ "Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity". Retrieved 30 December 2014.

^ ab H. Nahavandi, Y. Bomati, Shah Abbas, empereur de Perse (1587–1629) (Perrin, Paris, 1998)

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2015-10-23.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ M. Canard: Armīniya in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Leiden 1993.

^ Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond pp 729 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014

ISBN 1598849484

^ "Griboedov not only extended protection to those Caucasian captives who sought to go home but actively promoted the return of even those who did not volunteer. Large numbers of Georgian and Armenian captives had lived in Iran since 1804 or as far back as 1795."

Fisher, William Bayne;Avery, Peter; Gershevitch, Ilya; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles. The Cambridge History of Iran Cambridge University Press, 1991. p. 339.

^ (in Russian) A. S. Griboyedov. "Записка о переселеніи армянъ изъ Персіи въ наши области", Фундаментальная Электронная Библиотека

^ ab Bournoutian 1980, pp. 11, 13-14.

^ ab Bournoutian 1980, pp. 12-13.

^ Bournoutian 1980, p. 14.

^ Bournoutian 1980, pp. 11-13.

^ ab Bournoutian 1980, p. 13.

^ Kettenhofen, Bournoutian & Hewsen 1998, pp. 542-551.

^ Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger. Middle East and Africa: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 268.

^ ab Amurian, A.; Kasheff, M. (1986). "ARMENIANS OF MODERN IRAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

^ abc Arkun, Aram (1994). "DAŠNAK". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

^ http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/eprem-khan

^ Ormanian, Malachia (1911). Հայոց եկեղեցին և իր պատմութիւնը, վարդապետութիւնը, վարչութիւնը, բարեկարգութիւնը, արաողութիւնը, գրականութիւն, ու ներկայ կացութիւնը [The Church of Armenia: her history, doctrine, rule, discipline, liturgy, literature, and existing condition] (in Armenian). Constantinople. p. 266.

^ McCarthy, Justin (1983). Muslims and minorities: the population of Ottoman Anatolia and the end of the empire. New York: New York University press. ISBN 9780871509635

^ https://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/SOD.TAB5.1B.GIF

^ Bournoutian, George (2002). A Concise History of the Armenian People: (from Ancient Times to the Present) (2 ed.). Mazda Publishers. ISBN 978-1568591414.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-02-08. Retrieved 2015-02-08.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "Assessment for Christians in Iran". Minorities At Risk Project. 2006. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

^ Metz, Helen Chapin (1989). "Iran: a country study". Federal Research Division, Library of Congress: 96. Retrieved 28 May 2016.There were an estimated 300,000 Armenians in the country at the time of the Revolution in 1979.

^ Sanasarian, Eliz (2000). Religious Minorities in Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-1139429856.Armenians numbered an estimated 250,000 in 1979 (...)

^ "Sarkis Cathedral, Tehran – Lonely Planet Travel Guide". Lonelyplanet.com. 2012-01-07. Archived from the original on 2008-10-05. Retrieved 2012-03-21.

^ "Iran's religious minorities waning despite own MPs". Bahai.uga.edu. 2000-02-16. Retrieved 2012-03-21.

^ Golnaz Esfandiari (2004-12-23). "A Look At Iran's Christian Minority". Payvand. Retrieved 2012-03-21.

^ "Իրանի Կրոնական Փոքրամասնություններ". Lragir.am. 2013-06-30. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

^ ab Իրանահայ «Ալիք»- ը նշում է 80- ամյակը

^ Թամարա Վարդանյան. "Իրանահայ Համայնք. Ճամպրուկային Տրամադրություններ". Noravank.am. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

^ Հայկական Հանրագիտարան. "Հայերն Իրանում". Encyclopedia.am. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

^ Judith Pfeiffer. Politics, Patronage and the Transmission of Knowledge in 13th - 15th Century Tabriz page 270 BRILL, 7 nov. 2013

ISBN 978-9004262577

^ ab Christoph Werner. An Iranian Town in Transition: A Social and Economic History of the Elites of Tabriz, 1747-1848 page 90. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2000.

ISBN 978-3447043090

^ "Edmon Armenian history". Home.wanadoo.nl. Archived from the original on 2012-03-24. Retrieved 2012-03-21.

Sources

Bournoutian, George A. (1980). "The Population of Persian Armenia Prior to and Immediately Following its Annexation to the Russian Empire: 1826-1832". The Wilson Center, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies.

- Yves Bomati and Houchang Nahavandi,Shah Abbas, Emperor of Persia,1587-1629, 2017, ed. Ketab Corporation, Los Angeles,

ISBN 978-1595845672, English translation by Azizeh Azodi.

Amurian, A.; Kasheff, M. (1986). "ARMENIANS OF MODERN IRAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

Berberian, Houri (2008). "ARMENIA ii. ARMENIAN WOMEN IN THE LATE 19TH- AND EARLY 20TH-CENTURY PERSIA". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, P.; Hambly, G. R. G; Melville, C. (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521200954.

Kettenhofen, Erich; Bournoutian, George A.; Hewsen, Robert H. (1998). "EREVAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VIII, Fasc. 5. pp. 542–551.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Armenians in Iran. |

- Armenian Iranians news portal

- Hamaynk: Iranian Armenian News Network

- "Iranian Armenians" BBC Persian

- Alik, Armenian daily in Iran

- Arax Armenian weekly in Iran

- Hooys Armenian Biweekly