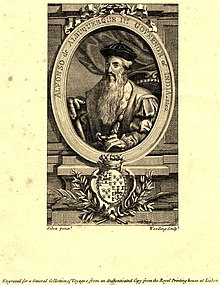

Afonso de Albuquerque

His Lordship Afonso de Albuquerque | |

|---|---|

| |

| Captain-Major of the Seas of Arabia Governor of Portuguese India | |

In office 4 November 1509 – September 1515 | |

| Monarch | Manuel I of Portugal |

| Preceded by | Francisco de Almeida |

| Succeeded by | Lopo Soares de Albergaria |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Afonso de Albuquerque c. 1453 Alhandra, Kingdom of Portugal |

| Died | 16 December 1515 Goa, Portuguese India |

| Nationality | Portuguese |

| Children | Brás de Albuquerque, 2nd Duke of Goa |

| Mother | Leonor de Menezes |

| Father | Gonçalo de Albuquerque |

| Occupation | Admiral Governor of India |

| Signature |  |

Afonso de Albuquerque, Duke of Goa (Portuguese pronunciation: [ɐˈfõsu dɨ aɫbuˈkɛɾk(ɨ)]; c. 1453 – 16 December 1515) (also spelled Aphonso or Alfonso), was a Portuguese general, a "great conqueror",[1][2][3] a statesman, and an empire builder.[4]

Afonso advanced the three-fold Portuguese grand scheme of combating Islam, spreading Christianity, and securing the trade of spices by establishing a Portuguese Asian empire.[5] Among his achievements, Afonso managed to conquer the island of Goa and was the first European of his Renaissance to raid the Persian Gulf, and he led the first voyage by a European fleet into the Red Sea.[6] His military and administrative works are generally regarded as among the most vital to building and securing the Portuguese Empire in the Orient, the Middle East, and the spice routes of eastern Oceania.[7]

Afonso is generally considered a military genius,[8][9] and "probably the greatest naval commander of the age"[10] given his successful strategy—he attempted to close all the Indian Ocean naval passages to the Atlantic, Red Sea, Persian Gulf, and to the Pacific, transforming it into a Portuguese mare clausum established over the opposition of the Ottoman Empire and its Muslim and Hindu allies.[11] In the expansion of the Portuguese Empire, Afonso initiated a rivalry that would become known as the Ottoman–Portuguese war, which would endure for many years. Many of the Ottoman–Portuguese conflicts in which he was directly involved took place in the Indian Ocean, in the Persian Gulf regions for control of the trade routes, and on the coasts of India. It was his military brilliance in these initial campaigns against the much larger Ottoman Empire and its allies that enabled Portugal to become the first global empire in history.[12] He had a record of engaging and defeating much larger armies and fleets. For example, his capture of Ormuz in 1507 against the Persians was accomplished with a fleet of seven ships.[13] Other famous battles and offensives which he led include the conquest of Goa in 1510 and the capture of Malacca in 1511. He became admiral of the Indian Ocean, and was appointed head of the "fleet of the Arabian and Persian sea" in 1506.[2]

During the last five years of his life, he turned to administration,[14] where his actions as the second governor of Portuguese India were crucial to the longevity of the Portuguese Empire. He pioneered European sea trade with China during the Ming Dynasty with envoy Rafael Perestrello, Thailand with Duarte Fernandes as envoy, and with Timor, passing through Malaysia and Indonesia in a voyage headed by António de Abreu and Francisco Serrão. He also aided diplomatic relations with Ethiopia using priest envoys João Gomes and João Sanches,[15][16][17][18][19] and established diplomatic ties with Persia, during the Safavid dynasty.[20]

He became known as "the Great",[1][14][21] "the Terrible",[22] "the Caesar of the East", "the Lion of the Seas", and "the Portuguese Mars".

Contents

1 Early life

2 Early military service

2.1 First expedition to India, 1503

2.2 Second expedition to India, 1506

2.2.1 First conquest of Socotra and Ormuz, 1507

2.2.2 Arrest at Cannanore, 1509

3 Governor of Portuguese India, 1509–1515

3.1 Conquest of Goa, 1510

3.2 Conquest of Malacca, 1511

3.2.1 Shipwreck on the Flor de la mar, 1511

3.3 Missions from Malacca

3.3.1 Embassies to Pegu, Sumatra and Siam, 1511

3.3.2 Expedition to the "spice islands" (Maluku islands), 1512

3.3.3 China expeditions, 1513

3.4 Return to Cochin and Goa

3.5 Campaign in the Red Sea, 1513

3.6 Submission of Calicut

3.7 Administration and diplomacy in Goa, 1514

3.8 Conquest of Ormuz and Illness

3.8.1 Death

4 Legacy

4.1 Global legacy

5 Titles and honours

6 Son

7 Ancestry

8 References

9 Bibliography

9.1 In other languages

9.2 Primary sources

10 External links

Early life

Coat of arms of Albuquerque

Afonso de Albuquerque was born in 1453 in Alhandra, near Lisbon.[23] He was the second son of Gonçalo de Albuquerque, Lord of Vila Verde dos Francos, and Dona Leonor de Menezes. His father held an important position at court and was connected by remote illegitimate descent with the Portuguese monarchy. He was educated in mathematics and Latin at the court of Afonso V of Portugal, where he befriended Prince John, the future King John II of Portugal.[24]

Afonso's early training is described by Diogo Barbosa Machado:

“D. Alfonso de Albuquerque, surnamed the Great, by reason of the heroic deeds wherewith he filled Europe with admiration, and Asia with fear and trembling, was born in the year 1453, in the Estate called, for the loveliness of its situation, the Paradise of the Town of Alhandra, six leagues distant from Lisbon. He was the second son of Gonçalo de Albuquerque, Lord of Villaverde, and of D. Leonor de Menezes, daughter of D. Álvaro Gonçalves de Athayde, Count of Atouguia, and of his wife D. Guiomar de Castro, and corrected this injustice of nature by climbing to the summit of every virtue, both political and moral. He was educated in the Palace of the King D. Afonso V, in whose palaestra he strove emulously to become the rival of that African Mars”.[25]

Early military service

Afonso served 10 years in North Africa, where he gained military experience in fierce campaigns against Muslim powers and Ottoman Turks.[21]

In 1471, under the command of Afonso V of Portugal, he was present at the conquest of Tangier and Arzila in Morocco,[21] serving there as an officer for some years. In 1476 he accompanied Prince John in wars against Castile, including the Battle of Toro. He participated in the campaign on the Italian peninsula in 1480 to rescue Ferdinand II of Aragon from the Ottoman invasion of Otranto that ended in victory.[14] On his return in 1481, when Prince John was crowned as King John II, Afonso was made Master of the Horse for his distinguished exploits, chief equerry (estribeiro-mor) to the King, a post which he held throughout John's reign (1481–95).[21][25] In 1489 he returned to military campaigns in North Africa, as commander of defense in the Graciosa fortress, an island in the river Luco near the city of Larache, and in 1490 was part of the guard of King John II, returning to Arzila in 1495, where his younger brother Martim died fighting by his side.

Afonso made his mark under the stern John II, and won military campaigns in Africa and the Mediterranean sea, yet Asia is where he would make his greatest impact.[21][25]

First expedition to India, 1503

When King Manuel I of Portugal was enthroned, he showed some reticence towards Afonso, a close friend of his dreaded predecessor and seventeen years his senior. Eight years later, on 6 April 1503, after a long military career and at a mature age, Afonso was sent on his first expedition to India together with his cousin Francisco de Albuquerque. Each commanded three ships, sailing with Duarte Pacheco Pereira and Nicolau Coelho. They engaged in several battles against the forces of the Zamorin of Calicut (Calecute, Kozhikode) and succeeded in establishing the King of Cohin (Cohim, Kochi) securely on his throne. In return, the King gave them permission to build the Portuguese fort Immanuel (Fort Kochi) and establish trade relations with Quilon (Coulão, Kollam). This laid the foundation for the eastern Portuguese Empire.[26]

Second expedition to India, 1506

Map of the Arabian Peninsula showing the Red Sea with Socotra island (red) and the Persian Gulf (blue) with the Strait of Hormuz (Cantino planisphere, 1502)

Afonso returned home in July 1504, and was well received by King Manuel I. After he assisted with the creation of a strategy for the Portuguese efforts in the east, King Manuel entrusted him with the command of a squadron of five vessels in the fleet of sixteen sailing for India in early 1506 headed by Tristão da Cunha.[26]

Their aim was to conquer Socotra and build a fortress there, hoping to close the trade in the Red Sea.

Afonso went as "chief-captain for the Coast of Arabia", sailing under da Cunha's orders until reaching Mozambique.[27] He carried a sealed letter with a secret mission ordered by the King: after fulfilling the first mission, he was to replace the first viceroy of India, Francisco de Almeida, whose term ended two years later.[28] Before departing, he legitimized a natural son born in 1500, and made his will.

First conquest of Socotra and Ormuz, 1507

The fleet left Lisbon on 6 April 1506. Afonso piloted his ship himself, having lost his appointed pilot on departure. In Mozambique Channel, they rescued Captain João da Nova, who had encountered difficulties on his return from India; da Nova and his ship, the Frol de la mar, joined da Cunha's fleet.[29] From Malindi, da Cunha sent envoys to Ethiopia, which at the time was thought to be closer than it actually is. Those included the priest João Gomes, João Sanches and Tunisian Sid Mohammed who, having failed to cross the region, headed for Socotra; from there, Afonso managed to land them in Filuk.[30]

After successful attacks on Arab cities on the east Africa coast, they conquered Socotra and built a fortress at Suq, hoping to establish a base to stop the Red Sea commerce to the Indian Ocean. However, Socotra was abandoned four years later, as it was not advantageous as a base.[28]

The Fort of Our Lady of the Conception, Hormuz Island, Iran

At Socotra, they parted ways: Tristão da Cunha sailed for India, where he would relieve the Portuguese besieged at Cannanore, while Afonso took seven ships and 500 men to Ormuz in the Persian Gulf, one of the chief eastern centers of commerce. On his way, he conquered the cities of Curiati (Kuryat), Muscat in July 1507, and Khor Fakkan, accepting the submission of the cities of Kalhat and Sohar. He arrived at Ormuz on 25 September and soon captured the city, which agreed to become a tributary state of the Portuguese king.

Statue of Afonso de Albuquerque, symbolically standing on a stack of weapons, referencing his reply in Hormuz

Hormuz was then a tributary state of Shah Ismail of Persia. In a famous episode, shortly after its conquest Albuquerque was confronted by Persian envoys, who demanded the payment of the due tribute from him instead. He ordered them to be given a stock of cannonballs, arrows and weapons, retorting that "such was the currency struck in Portugal to pay the tribute demanded from the dominions of King Manuel"[31]

According to Brás de Albuquerque, it was Shah Ismael who coined the term "Lion of the seas", addressing Albuquerque as such. Afonso began building the Fort of Our Lady of Victory (later renamed Fort of Our Lady of the Conception),[32] engaging his men of all ranks in the work.

However, some of his officers revolted against the heavy work and climate and, claiming that Afonso was exceeding his orders, departed for India. With the fleet reduced to two ships and left without supplies, he was unable to maintain this position for long. Forced to abandon Ormuz in January 1508, he raided coastal villages to resupply the settlement of Socotra, returned to Ormuz, and then headed to India.

Arrest at Cannanore, 1509

Afonso arrived at Cannanore on the Malabar coast in December 1508, where he opened before the viceroy, Dom Francisco de Almeida, the sealed letter which he had received from the King, and which named as governor to succeed Almeida.[28][33][34]

The viceroy, supported by the officers who had abandoned Afonso at Ormuz, had a matching royal order, but declined to yield, protesting that his term ended only in January and stating his intention to avenge his son's death by fighting the Mamluk fleet of Mirocem, refusing Afonso's offer to fight him himself. Afonso avoided confrontation, which could have led to civil war, and moved to Kochi, India, to await further instruction from the King, maintaining his entourage himself. He was described by Fernão Lopes de Castanheda as patiently enduring open opposition from the group that had gathered around Almeida, with whom he kept formal contact. Increasingly isolated, he wrote to Diogo Lopes de Sequeira, who arrived in India with a new fleet, but was ignored as Sequeira joined the Viceroy. At the same time, Afonso refused approaches from opponents of the Viceroy, who encouraged him to seize power.[35]

On 3 February 1509, Almeida fought the naval Battle of Diu against a joint fleet of Mamluks, Ottomans, the Zamorin of Calicut, and the Sultan of Gujarat, regarding it as personal revenge for the death of his son. His victory was decisive: the Ottomans and Mamluks abandoned the Indian Ocean, easing the way for Portuguese rule there for the next century. In August, after a petition from Afonso's former officers with the support of Diogo Lopes de Sequeira claiming him unfit for governance, Afonso was sent in custody to St. Angelo Fort in Cannanore.[36][37] There he remained under what he considered to be imprisonment.

In September 1509, Sequeira tried to establish contact with the Sultan of Malacca but failed, leaving behind 19 Portuguese prisoners.

Governor of Portuguese India, 1509–1515

Afonso was released after three months' confinement, on the arrival at Cannanore of the Marshal of Portugal with a large fleet.[26][38]

The Portuguese Marshal was the most important Portuguese noble ever to visit India and he brought an armada of fifteen ships and 3,000 men sent by the King to defend Afonso's rights, and to take Calicut.[39]

On 4 November 1509, Afonso became the second Governor of the State of India, a position he would hold until his death. Almeida having returned home in 1510,[40] Afonso speedily showed the energy and determination of his character.[41] He intended to dominate the Muslim world and control the Spice trade.[41]

Initially King Manuel I and his council in Lisbon tried to distribute the power, outlining three areas of jurisdiction in the Indian Ocean.[28] In 1509, the nobleman Diogo Lopes de Sequeira was sent with a fleet to Southeast Asia, to seek an agreement with Sultan Mahmud Shah of Malacca, but failed and returned to Portugal. To Jorge de Aguiar was given the region between the Cape of Good Hope and Gujarat. He was succeeded by Duarte de Lemos, but left for Cochin and then for Portugal, leaving his fleet to Afonso.

Conquest of Goa, 1510

Illustration depicts the aftermath of the Portuguese conquest of Goa, from the forces of Yusuf Adil Shah.

In January 1510, obeying the orders from the King and aware of the absence of Zamorin, Afonso advanced on Calicut. The attack was unsuccessful, as Marshal Fernando Coutinho ventured into the inner city against instructions, fascinated by its richness, and was ambushed. During the rescue, Afonso was shot in the chest and had to retreat, barely escaping with his life. Coutinho was killed during the escape. [28]

Soon after the failed attack, Afonso assembled a fleet of 23 ships and 1200 men. Contemporary reports state that he wanted to fight the Egyptian Mamluk Sultanate fleet in the Red Sea or return to Hormuz. However, he had been informed by Timoji (a privateer in the service of the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire) that it would be easier to fight them in Goa, where they had sheltered after the Battle of Diu,[42] and also of the illness of the Sultan Yusuf Adil Shah, and war between the Deccan sultanates.[42] So he relied on surprise in the capture of Goa from the Sultanate of Bijapur. He thus completed another mission, for Portugal wanted not to be seen as an eternal "guest" of Kochi and had been coveting Goa as the best trading port in the region.

A first assault took place in Goa from 4 March to 20 May 1510. After initial occupation, feeling unable to hold the city given the poor condition of its fortifications, the cooling of Hindu residents' support and insubordination among his ranks following an attack by Ismail Adil Shah, Afonso refused a truce offered by the Sultan and abandoned the city in August. His fleet was scattered, and a palace revolt in Kochi hindered his recovery, so he headed to Fort Anjediva. New ships arrived from Portugal, which were intended for the nobleman Diogo Mendes de Vasconcelos at Malacca, who had been given a rival command of the region.

Three months later, on 25 November Afonso reappeared at Goa with a renovated fleet. Diogo Mendes de Vasconcelos was compelled to accompany him with the reinforcements for Malacca[28] and about 300 Malabari reinforcements from Cannanore. In less than a day, they took Goa from Ismail Adil Shah and his Ottoman allies, who surrendered on 10 December. It is estimated that 6000 of the 9000 Muslim defenders of the city died, either in the fierce battle in the streets or by drowning while trying to escape.[43] Afonso regained the support of the Hindu population, although he frustrated the initial expectations of Timoji, who aspired to become governor. Afonso rewarded him by appointing him chief "Aguazil" of the city, an administrator and representative of the Hindu and Muslim people, as a knowledgeable interpreter of the local customs.[42] He then made an agreement to lower the yearly tribute.

Coining of money for d'Albuquerque at Goa (1510)

In Goa, Afonso established the first Portuguese mint in the East, after Timoja's merchants had complained of the scarcity of currency, taking it as an opportunity to solidify the territorial conquest.[44] The new coin, based on the existing local coins, showed a cross on the obverse and an armillary sphere (or "esfera"), King Manuel's badge, on the reverse. Gold cruzados or manueis, silver esferas and alf-esferas, and bronze "leais" were issued.[45][46] Another mint was established at Malacca in 1511.

Albuquerque founded at Goa the Hospital Real de Goa or Royal Hospital of Goa, by the Church of Santa Catarina. Upon hearing that the doctors were extorting the sickly with excessive fees, Albuquerque summoned them, declaring that "You charge a physicians' pay and don't know what disease the men who serve our lord the King suffer from. Thus, I want to teach you what is it that they die from"[47] and put them to work building the city walls all day till nightfall before releasing them.[48]

Despite constant attacks, Goa became the center of Portuguese India, with the conquest triggering the compliance of neighbouring kingdoms: the Sultan of Gujarat and the Zamorin of Calicut sent embassies, offering alliances and local grants to fortify.

Afonso then used Goa to secure the Spice trade in favor of Portugal and sell Persian horses to Vijayanagara and Hindu princes in return for their assistance.[49]

Conquest of Malacca, 1511

Malacca, with A Famosa, depicted by Albuquerque's scrivener, Gaspar Correia.

Afonso explained to his armies why the Portuguese wanted to capture Malacca:

- "The King of Portugal has often commanded me to go to the Straits, because...this was the best place to intercept the trade which the Moslems...carry on in these parts. So it was to do Our Lord’s service that we were brought here; by taking Malacca, we would close the Straits so that never again would the Moslems be able to bring their spices by this route.... I am very sure that, if this Malacca trade is taken out of their hands, Cairo and Mecca will be completely lost." (The Commentaries of the Great Afonso de Albuquerque)

The surviving gate of the A Famosa Portuguese fortress in Malacca

In February 1511, through a friendly Hindu merchant, Nina Chatu, Afonso received a letter from Rui de Araújo, one of the nineteen Portuguese held at Malacca since 1509. It urged moving forward with the largest possible fleet to demand their release, and gave details of the fortifications. Afonso showed it to Diogo Mendes de Vasconcelos, as an argument to advance in a joint fleet. In April 1511, after fortifying Goa, he gathered a force of about 900 Portuguese, 200 Hindu mercenaries and about eighteen ships.[50] He then sailed to Malacca against orders and despite the protest of Diogo Mendes, who claimed command of the expedition. Afonso eventually centralized the Portuguese government in the Indian Ocean. After the Malaccan conquest he wrote a letter to the King to explain his disagreement with Diogo Mendes, suggesting that further divisions could be harmful to the Portuguese in India.[28] Under his command was Ferdinand Magellan, who had participated in the failed embassy of Diogo Lopes de Sequeira in 1509.

After a false start towards the Red Sea, they sailed to the Strait of Malacca. It was the richest city that the Portuguese tried to take, and a focal point in the trade network where Malay traders met Gujarati, Chinese, Japanese, Javanese, Bengali, Persian and Arabic, among others, described by Tomé Pires as of invaluable richness. Despite its wealth, it was mostly a wooden-built city, with few masonry buildings but was defended by a mercenary force estimated at 20,000 men and more than 2000 pieces of artillery. Its greatest weakness was the unpopularity of the government of Sultan Mahmud Shah, who favoured Muslims, arousing dissatisfaction amongst other merchants.

Afonso made a bold approach to the city, his ships decorated with banners, firing cannon volleys. He declared himself lord of all the navigation, demanded the Sultan release the prisoners and pay for damages, and demanded consent to build a fortified trading post. The Sultan eventually freed the prisoners, but was unimpressed by the small Portuguese contingent. Afonso then burned some ships at the port and four coastal buildings as a demonstration. The city being divided by the Malacca River, the connecting bridge was a strategic point, so at dawn on 25 July the Portuguese landed and fought a tough battle, facing poisoned arrows, taking the bridge in the evening. After fruitlessly waiting for the Sultan's reaction, they returned to the ships and prepared a junk (offered by Chinese merchants), filling it with men, artillery and sandbags. Commanded by António de Abreu, it sailed upriver at high tide to the bridge. The day after, all had landed. After a fierce fight during which the Sultan appeared with an army of war elephants, the defenders were dispersed and the Sultan fled.[28] Afonso waited for the reaction of the Sultan. Merchants approached, asking for Portuguese protection. They were given banners to mark their premises, a sign that they would not be looted. On 15 August, the Portuguese attacked again, but the Sultan had fled the city. Under strict orders, they looted the city, but respected the banners.[51]

Afonso prepared Malacca's defenses against a Malay counterattack,[50] building a fortress, assigning his men to shifts and using stones from the mosque and the cemetery. Despite the delays caused by heat and malaria, it was completed in November 1511, its surviving door now known as "A Famosa" ('the famous'). It was possibly then that Afonso had a large stone engraved with the names of the participants in the conquest. To quell disagreements over the order of the names, he had it set facing the wall, with the single inscription Lapidem quem reprobaverunt aedificantes (Latin for "The stone the builders rejected", from David's prophecy, Psalm 118:22–23) on the front.[52]

He settled the Portuguese administration, reappointing Rui de Araújo as factor, a post assigned before his 1509 arrest, and appointing rich merchant Nina Chatu to replace the previous bendahara, representative of the Kafir people and adviser. Besides assisting in the governance of the city and first Portuguese coinage, he provided the junks for several diplomatic missions.[53] Meanwhile, Afonso arrested and had executed the powerful Javanese merchant Utimuti Raja who, after being appointed to a position in the Portuguese administration as representative of the Javanese population, had maintained contacts with the exiled royal family.

Afonso arranged for the shipping of many Órfãs d'El-Rei[54][55] to Portuguese Malacca.

Shipwreck on the Flor de la mar, 1511

On 20 November 1511 Afonso sailed from Malacca to the coast of Malabar on the old Flor de la Mar carrack that had served to support the conquest of Malacca. Despite its unsound condition, he used it to transport the treasure amassed in the conquest, given its large capacity.[28] He wanted to give the court of King Manuel a show of Malaccan treasures. There were also the offers from the Kingdom of Siam (Thailand) to the King of Portugal and all his own fortune. On the voyage the Flor de la Mar was wrecked in a storm, and Afonso barely escaped drowning.[50]

Missions from Malacca

Embassies to Pegu, Sumatra and Siam, 1511

Most Muslim and Gujarati merchants having fled the city, Afonso invested in diplomatic efforts demonstrating generosity to Southeast Asian merchants, like the Chinese, to encourage good relations with the Portuguese. Trade and diplomatic missions were sent to continental kingdoms: Rui Nunes da Cunha was sent to Pegu (Burma), from where King Binyaram sent back a friendly emissary to Kochi in 1514[56][57] and Sumatra, Sumatran kings of Kampar and Indragiri sending emissaries to Afonso accepting the new power, as vassal states of Malacca.[58] Knowing of Siamese ambitions over Malacca, Afonso sent Duarte Fernandes in a diplomatic mission to the Kingdom of Siam (Thailand), returning in a Chinese junk. He was one of the Portuguese who had been arrested in Malacca, having gathered knowledge about the culture of the region. There he was the first European to arrive, establishing amicable relations between the kingdom of Portugal and the court of the King of Siam Ramathibodi II, returning with a Siamese envoy bearing gifts and letters to Afonso and the King of Portugal.[58]

Expedition to the "spice islands" (Maluku islands), 1512

Depiction of Ternate with São João Baptista Fort, built in 1522

In November, after having secured Malacca and learning the location of the then secret "spice islands", Afonso sent three ships to find them, led by trusted António de Abreu with deputy commander Francisco Serrão.[59]Malay sailors were recruited to guide them through Java, the Lesser Sunda Islands and the Ambon Island to Banda Islands, where they arrived in early 1512.[60] There they remained for a month, buying and filling their ships with nutmeg and cloves. António de Abreu then sailed to Amboina whilst Serrão sailed towards the Moluccas, but he was shipwrecked near Seram. Sultan Abu Lais of Ternate heard of their stranding, and, seeing a chance to ally himself with a powerful foreign nation, brought them to Ternate in 1512 where they were permitted to build a fort on the island, the Forte de São João Baptista de Ternate (pt, built in 1522.)

China expeditions, 1513

In early 1513, Jorge Álvares, sailing on a mission under Afonso's orders, was allowed to land in Lintin Island, on the Pearl River Delta in southern China. Soon after, Afonso sent Rafael Perestrello to southern China, seeking trade relations with the Ming dynasty. In ships from Portuguese Malacca, Rafael sailed to Canton (Guangzhou) in 1513, and again from 1515 to 1516 to trade with Chinese merchants. These ventures, along with those of Tomé Pires and Fernão Pires de Andrade, were the first direct European diplomatic and commercial ties with China. However, after the death of the Chinese Zhengde Emperor on 19 April 1521, conservative factions at court seeking to limit eunuch influence rejected the new Portuguese embassy, fought sea battles with the Portuguese around Tuen Mun, and Tomé was forced to write letters to Malacca stating that he and other ambassadors would not be released from prison in China until the Portuguese relinquished their control of Malacca and returned it to the deposed Sultan of Malacca (who was previously a Ming tributary vassal).[61] Nonetheless, Portuguese relations with China became normalized again by the 1540s and in 1557 a permanent Portuguese base at Macau in southern China was established with consent from the Ming court.

Return to Cochin and Goa

Afonso de Albuquerque as governor of India

Afonso returned from Malacca to Cochin, but could not sail to Goa as it faced a serious revolt headed by the forces of Ismael Adil Shah, the Sultan of Bijapur, commanded by Rasul Khan and his countrymen. During Afonso's absence from Malacca, Portuguese who opposed the taking of Goa had waived its possession, even writing to the King that it would be best to let it go. Held up by the monsoon and with few forces available, Afonso had to wait for the arrival of reinforcement fleets headed by his nephew D. Garcia de Noronha, and Jorge de Mello Pereira.

While at Cochin, Albuquerque started a school. In a private letter to King Manuel I, he states that he had found a chest full of books with which to teach the children of married Portuguese settlers (casados) and Christian converts to read and write which, according to Albuquerque, there were about a hundred in his time, "all very sharp and easily learn what they are taught".[62]

On 10 September 1512, Afonso sailed from Cochin to Goa with fourteen ships carrying 1,700 soldiers. Determined to recapture the fortress, he ordered trenches dug and a wall breached. But on the day of the planned final assault, Rasul Khan surrendered. Afonso demanded the fort be handed over with its artillery, ammunition and horses, and the deserters to be given up. Some had joined Rasul Khan when the Portuguese were forced to flee Goa in May 1510, others during the recent siege. Rasul Khan consented, on condition that their lives be spared. Afonso agreed and he left Goa. He did spare the lives of the deserters, but had them horribly mutilated. One such renegade was Fernão Lopes, bound for Portugal in custody, who escaped at the island of Saint Helena and led a 'Robinson Crusoe' life for many years. After such measures the town became the most prosperous Portuguese settlement in India.

Campaign in the Red Sea, 1513

In December 1512 an envoy from Ethiopia arrived at Goa. Mateus was sent by the regent queen Eleni, following the arrival of the Portuguese from Socotra in 1507, as an ambassador for the king of Portugal in search of a coalition to help face growing Muslim influence. He was received in Goa with great honour by Afonso, as a long-sought "Prester John" envoy. His arrival was announced by King Manuel to Pope Leo X in 1513. Although Mateus faced the distrust of Afonso's rivals, who tried to prove he was some impostor or Muslim spy, Afonso sent him to Portugal.[63] The King is described as having wept with joy at their report.

In February 1513, while Mateus was in Portugal, Afonso sailed to the Red Sea with a force of about 1000 Portuguese and 400 Malabaris. He was under orders to secure that channel for Portugal. Socotra had proved ineffective to control the Red Sea entrance and was abandoned, and Afonso's hint that Massawa could be a good Portuguese base might have been influenced by Mateus' reports.[28]

Knowing that the Mamluks were preparing a second fleet at Suez, he wanted to advance before reinforcements arrived in Aden, and accordingly laid siege to the city.[64] Aden was a fortified city, but although he had scaling ladders they broke during the chaotic attack. After half a day of fierce battle Afonso was forced to retreat. He cruised the Red Sea inside the Bab al-Mandab, with the first European fleet to have sailed this route. He attempted to reach Jeddah, but the winds were unfavourable and so he sheltered at Kamaran island in May, until sickness among the men and lack of fresh water forced him to retreat. In August 1513, after a second attempt to reach Aden, he returned to India with no substantial results. In order to destroy the power of Egypt, he wrote to King Manuel of the idea of diverting the course of the Nile river to render the whole country barren. Perhaps most tellingly, he intended to steal the body of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad, and hold it for ransom until all Muslims had left the Holy Land.[65][66]

Although Albuquerque's expedition failed to reach Suez, such an incursion into the Red Sea by a Christian fleet for the first time in history stunned the Muslim world, and panic spread in Cairo.[67]

Submission of Calicut

The Portuguese fort at Calicut

Albuquerque achieved during his term a favourable end to hostilities between the Portuguese and the Zamorin of Calicut, which had lasted ever since the massacre of the Portuguese in Calicut in 1502. As naval trade faltered and vassals defected, with no foreseeable solutions to the conflict with the Portuguese, the court of the Zamorin fell to in-fighting. The ruling Zamorin was assassinated and replaced by a rival, under the instigation of Albuquerque. Thus, peace talks could commence. the Portuguese were allowed to build a fortress in Calicut itself, and acquired rights to obtain as much pepper and ginger as they wished, at stipulated prices, and half the customs of Calicut as yearly tribute.[68] Construction of the fortress began immediately, under the guise of chief-architect Tomás Fernandes.

Administration and diplomacy in Goa, 1514

Dürer's Rhinoceros, woodcut (1515)

Portuguese and Christian women of India, depicted in the Códice Casanatense

With peace concluded, in 1514 Afonso devoted himself to governing Goa and receiving embassies from Indian governors, strengthening the city and encouraging marriages of Portuguese men and local women. At that time, Portuguese women were barred from traveling overseas. In 1511 under a policy which Afonso promulgated, the Portuguese government encouraged their explorers to marry local women. To promote settlement, the King of Portugal granted freeman status and exemption from Crown taxes to Portuguese men (known as casados, or "married men") who ventured overseas and married local women. With Afonso's encouragement, mixed marriages flourished. He appointed local people for positions in the Portuguese administration and did not interfere with local traditions (except "sati", the practice of immolating widows, which he banned).

In March 1514 King Manuel sent to Pope Leo X a huge and exotic embassy led by Tristão da Cunha, who toured the streets of Rome in an extravagant procession of animals from the colonies and wealth from the Indies. His reputation reached its peak, laying foundations of the Portuguese Empire in the East.

In early 1514, Afonso sent ambassadors to Gujarat's Sultan Muzaffar Shah II, ruler of Cambay, to seek permission to build a fort on Diu, India. The mission returned without an agreement, but diplomatic gifts were exchanged, including an Indian rhinoceros.[69] Afonso sent the gift, named ganda, and its Indian keeper, Ocem, to King Manuel.[70] In late 1515, Manuel sent it as a gift, the famous Dürer's Rhinoceros to Pope Leo X. Dürer never saw the actual rhinoceros, which was the first living example seen in Europe since Roman times.

Conquest of Ormuz and Illness

Afonso de Albuquerque as Governor of India

In 1513, at Cannanore, Afonso was visited by a Persian ambassador from Shah Ismail I, who had sent ambassadors to Gujarat, Ormuz and Bijapur. The shah's ambassador to Bijapur invited Afonso to send back an envoy to Persia. Miguel Ferreira was sent via Ormuz to Tabriz, where he had several interviews with the shah about common goals on defeating the Mamluk sultan.

At the same time, Albuquerque decided to conclude the effective conquest of Hormuz. He had learned that after the Portuguese retreat in 1507, a young king was reigning under the influence of a powerful Persian vizier, Reis Hamed, whom the king greatly feared. At Ormuz in March 1515, Afonso met the king and asked the vizier to be present. He then had him immediately stabbed and killed by his entourage, thus "freeing" the dominated king, so the island in the Persian Gulf yielded to him without resistance and remained a vassal state of the Portuguese Empire. Ormuz itself would not be Persian territory for another century, until a British-Persian alliance finally expelled the Portuguese in 1622.[71] At Ormuz, Afonso met with Miguel Ferreira, returning with rich presents and an ambassador, carrying a letter from the Persian potentate Shah Ismael, inviting Afonso to become a leading lord in Persia.[72] There he remained, engaging in diplomatic efforts, receiving envoys and overseeing the construction of the new fortress, while becoming increasingly ill. His illness was reported as early as September 1515.[73]

In November 1515, he embarked back to Goa, a journey he would not live to complete.

Death

Afonso's life ended on a bitter note, with a painful and ignominious close. At this time, his political enemies at the Portuguese court were planning his downfall. They had lost no opportunity in stirring up the jealousy of King Manuel against him, insinuating that Afonso intended to usurp power in Portuguese India.[74]

While on his return voyage from Ormuz in the Persian Gulf, near the harbor of Chaul, he received news of a Portuguese fleet arriving from Europe, bearing dispatches announcing that he was to be replaced by his personal foe, Lopo Soares de Albergaria. Realizing the plot that his enemies had moved against him, profoundly disillusioned, he voiced his bitterness: "Grave must be my sins before the King, for I am in ill favor with the King for love of the men, and with the men for love of the King."[75]

Feeling himself near death, he donned the surcoat of the Order of Santiago, which he was a knight of, and drew up his will, appointed the captain and senior officials of Ormuz, and organized a final council with his captains to decide the main matters affecting the Portuguese State of India.[73]

He wrote a brief letter to King Manuel, asking him to confer onto his natural son "all of the high honors and rewards" that were justly due to Afonso. He wrote in dignified and affectionate terms, assuring Manuel of his loyalty.[71][76]

On 16 December 1515, Afonso de Albuquerque died within sight of Goa. As his death was known, in the city "grait wailing arose"[77], and many took to the streets to witness his body carried on a chair by his main captains, in a procession lit by torches amidst the crowd.[78]

Afonso's body was buried in Goa, according to his will, in the Church of Nossa Senhora da Serra (Our Lady of the Hill), which he had been built in 1513 to thank the Madonna for his escape from Kamaran island.[79] That night, even the Hindu natives of Goa gathered to mourn him alongside the Portuguese, "for he was much loved by all"[80], and it was said that "God had need of him for war, and for that he had taken him"[81][73].

In Portugal, King Manuel's zigzagging policies continued, still trapped by the constraints of real-time medieval communication between Lisbon and India and unaware that Afonso was dead. Hearing rumours that the Mamluk Sultan of Egypt was preparing a magnificent army at Suez to prevent the conquest of Ormuz, he repented of having replaced Afonso, and in March 1516 urgently wrote to Albergaria to return the command of all operations to Afonso and provide him with resources to face the Egyptian threat. He organized a new Portuguese navy in Asia, with orders that Afonso (if he was still in India), be made commander-in-chief against the Sultan of Cairo's armies. Manuel would afterwards learn that Afonso had died many months earlier, and that his reversed decision had been delivered many months too late.[74][73]

After 51 years, in 1566, his body was moved to Nossa Senhora da Graça church in Lisbon,[82] which was ruined and rebuilt after the 1755 Great Lisbon earthquake.

Legacy

Albuquerque Monument on Afonso de Albuquerque Square in Lisbon (1902)

King Manuel I of Portugal was belatedly convinced of Afonso's loyalty, and endeavoured to atone for his lack of confidence in Afonso by heaping honours upon his son, Brás de Albuquerque (1500–1580),[83] whom he renamed "Afonso" in memory of the father.

Afonso de Albuquerque was a prolific writer, having sent numerous letters to the king during his governorship, covering topics from minor issues to major strategies. In 1557 his son published a collection of his letters under the title Commentarios do Grande Affonso d'Alboquerque[84]- a clear reference to Caesar's Commentaries- which he reviewed and re-published in 1576. There Afonso was described as "a man of middle stature, with a long face, fresh complexion, the nose somewhat large. He was a prudent man, and a Latin scholar, and spoke in elegant phrases; his conversation and writings showed his excellent education. He was of ready words, very authoritative in his commands, very circumspect in his dealings with the Moors, and greatly feared yet greatly loved by all, a quality rarely found united in one captain. He was very valiant and favoured by fortune."[85]

In 1572, Afonso's feats were described in The Lusiads, the Portuguese main epic poem by Luís Vaz de Camões (Canto X, strophes 40–49). The poet praises his achievements, but has the muses frown upon the harsh rule of his men, of whom Camões was almost a contemporary fellow. In 1934, Afonso was celebrated by Fernando Pessoa in Mensagem, a symbolist epic. In the first part of this work, called "Brasão" (Coat-of-Arms), he relates Portuguese historical protagonists to each of the fields in the Portuguese coat-of-arms, Afonso being one of the wings of the griffin headed by Henry the Navigator, the other wing being King John II.

A variety of mango that he used to bring on his journeys to India has been named in his honour.[86]

Numerous homages have been paid to Afonso; he is featured in the Padrão dos Descobrimentos monument; there is a square carrying his name in the Portuguese capital of Lisbon, which also features a bronze statue; two Portuguese Navy ships have been named in his honour: the sloop NRP Afonso de Albuquerque (1884) and the warship NRP Afonso de Albuquerque, the latter belonging to a sloop class named Albuquerque.

Global legacy

Portuguese discoveries and explorations: first arrival places and dates; main Portuguese spice trade routes in the Indian Ocean (blue)

The fabled Spice Islands were on the imagination of Europe since ancient times. In the 2nd century AD, the Malay Peninsula was known by the Greek philosopher Ptolemy, who labeled it 'Aurea Chersonesus"; and who said that it was believed the fabled area held gold in abundance. Even Indian traders referred to the East Pacific region as "Land of Gold" and made regular visits to Malaya in search of the precious metal, tin and sweet scented jungle woods.[87] But neither Ptolemy, nor Rome, nor Alexander was able to see the fabled regions of the East Pacific. Afonso de Albuquerque became the first European to reach the Spice Islands. Upon discovering the Malay Archipelago, he proceeded in 1511 to conquer Malacca, then commissioned an expedition under the command of António de Abreu and Vice-Commander Francisco Serrão (the latter being a cousin of Magellan) to further explore the extremities of the region in east Indonesia.[88] As a result of these voyages of exploration, the Portuguese became the first Europeans to discover and to reach the fabled Spice Islands in the Indies in addition to discovering their sea routes. Afonso found what had evaded Columbus' grasp – the wealth of the Orient. His discoveries did not go unnoticed, and it took little time for Magellan to arrive in the same region a few years later and discover the Philippines for Spain, giving birth to the Papal Treaty of Zaragoza.

Afonso's operations sent a voyage pushing further south which made the European discovery of Timor in the far south of Oceania, and the discovery of Papua New Guinea in 1512. This was followed up by another Portuguese, Jorge de Menezes in 1526, who named Papua New Guinea, the "Island of the Papua".[89][90][91][92]

Through Afonso's diplomatic activities, Portugal opened the sea between Europe and China. As early as 1513, Jorge de Albuquerque, a Portuguese commanding officer in Malacca, sent his subordinate Jorge Álvares to sail to China on a ship loaded with pepper from Sumatra. After sailing across the sea, Jorge Álvares and his crew dropped anchor in Tamao, an island located at the mouth of the Pearl River. This was the first Portuguese to set foot in the territory known as China, the mythical "Middle Kingdom" where they erected a stone Padrão.[93] Álvares is the first European to reach Chinese land by sea,[94][95][96][97] and, the first European to enter Hong Kong.[98][99] In 1514 Afonso de Albuquerque, the Viceroy of the Estado da India dispatched Rafael Perestrello to sail to China in order to pioneer European trade relations with the Chinese nation.[100] Rafael Perestrelo was quoted as saying, "being a very good and honest people, the Chinese hope to make friends with the Portuguese."[101] In spite of initial harmony and excitement between the two empires, difficulties soon arose.[102] Portugal's efforts in establishing lasting ties with China did pay off in the long run; the Portuguese colonized Macau, and established the first European permanent settlement on Chinese soil, which served as a permanent colonial base in southern China, and the two empires maintained an exchange in culture and trade for nearly 500 years.[103][104] The longest empire in history (1515–1999), begun by Afonso de Albuquerque five centuries earlier, ended when Portugal ceded the government of Macau to China.[105][106][107]

Allegorical fresco dedicated to Afonso de Albuquerque, present at the palace of justice of Vila Franca de Xira, in Portugal. Executed by Jaime Martins Barata

Afonso de Albuquerque pioneered trade relations with Thailand, and was as such the first recorded European to contact Thailand.[108]

Titles and honours

- Captain-Major of the Sea of Arabia

- 2nd Governor of India

1st Duke of Goa (posthumous)- A knight of the Portuguese Order of Saint James of the Sword

Fidalgo of the Royal Household

Son

Afonso de Albuquerque had a bastard son with an unrecorded woman. He legitimized the boy in February 1506. Before his death, he asked King Manuel I to leave to the son all his wealth and that the King oversee the son's education. When Afonso died, Manuel I renamed the child "Afonso" in his father's memory. Brás Afonso de Albuquerque, or Braz in the old spelling, was born in 1500 and died in 1580.

Ancestry

.mw-parser-output table.ahnentafel{border-collapse:separate;border-spacing:0;line-height:130%}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel tr{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel-t{border-top:#000 solid 1px;border-left:#000 solid 1px}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel-b{border-bottom:#000 solid 1px;border-left:#000 solid 1px}

| Ancestors of Afonso de Albuquerque | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

^ ab (Henry Morse Stephens 1897, p. 1)

^ ab “ALBUQUERQUE, ALFONSO DE”, Vol. I, Fasc. 8, pp. 823–824, J. Aubin, Encyclopædia Iranica

^ The Greenwood Dictionary of World History By John J. Butt, p. 10

^ Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. Vol. 1, by Keat Gin Ooi; p. 137

^ Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East ..., Volume 1 edited by Keat Gin Ooi. p. 17

^ A new collection of voyages and travels. (1711) [ed. by J. Stevens]. 2 vols. Oxford University p. 113

^ "New Year's resolutions..." algarvedailynews.com. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Afonso De Albuquerque; John Villiers; Thomas Foster Earle (1990). Albuquerque, Caesar of the East: Selected Texts by Afonso de Albuquerque and His Son. Aris & Phillips. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-85668-488-3.

^ Bailey Wallys Diffie; George Davison Winius (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese Empire: 1415–1580. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-0782-2.

^ Merle Calvin Ricklefs (2002). A History of Modern Indonesia Since ca. 1200. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8047-4480-5.

^ "ALBUQUERQUE, ALPHONSO". Encyclopædia Britannica 1911 (Net Industries). Archived from the original on 9 May 2006. Retrieved 10 May 2006.

^ China Goes to Sea: Maritime Transformation in Comparative Historical Perspective edited by Andrew Erickson, Lyle J. Goldstein Naval Institute Press, 2012. p. 403

^ Sykes, Sir Percy Molesworth (1 January 1921). A History of Persia. Macmillan and Company, limited. p. 186.

^ abc "Afonzo de Albuquerque". CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA. Newadvent.org. 1 March 1907. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

^ [1] O Preste João : mito, literatura e história. By Vilhena, Maria da Conceição. pp. 641, 642 (Universidade dos Açores) ("ARQUIPÉLAGO. História".

ISSN 0871-7664. 2ª série, vol. 5 (2001): 627–649) (2001)

^ John Jeremy Hespeler-Boultbee (2011). A Story in Stones: Portugal's Influence on Culture and Architecture in the Highlands of Ethiopia 1493–1634. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-926585-99-4.

^ Cecil H. Clough (1994). The European Outthrust and Encounter – The First Phase, 1400–1700: Essays in Tribute to David Beers Quinn on His 85th Birthday. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-85323-229-2.

^ (Damião de Góis, Chronica do Feliçissimo rei dom Manuel [1566], Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade, 1954, Part III, chapter lix) and (Armando Cortesão, Esparsos, Coimbra: Imprensa de Coimbra, 1974, pp. 25, 77–81.)

^ "Afonso de Albuquerque Blog: My Second Expedition to India: First Conquest of Socotra and Hormuz, 1507". afonsodealbuquerqueblog.blogspot.com.au. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

^ Couto, Dejanirah; Loureiro, Rui (2008). Revisiting Hormuz: Portuguese Interactions in the Persian Gulf Region in the Early Modern Period. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 219. ISBN 978-3-447-05731-8.

^ abcde "Afonso de Albuquerque". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

^ The Career and Legend of Vasco Da Gama, by Sanjay Subrahmanyam, p. 365

^ Robert Crowley; Geoffrey Parker (1 December 1996). Albuquerque, Afonso de. The Reader's Companion to Military History. Houghton Mifflin.

^ (Henry Morse Stephens 1897)

^ abc Vasco Da Gama, By Kingsley Garland Jayne; pp. 78–79, Taylor & Francis (1970)

^ abc Chisholm 1911.

^ Diogo do Couto, Décadas da Ásia, década X, livro I

^ abcdefghij Foundations of the Portuguese empire, 1415–1580, pp. 239–260, Bailey Wallys Diffie, Boyd C. Shafer, George Davison Winius

^ Afonso de Albuquerque; Walter de Gray Birch (2000). Commentaries of the Great Afonso – 4 Vols. ISBN 978-81-206-1514-4.

^ J. J. Hespeler-Boultbee (2006). A Story in Stones: Portugal's Influence on Culture and Architecture in the Highlands of Ethiopia, 1493–1634. CCB Publishing. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-9781162-1-7.

^ In Portuguese: [...]mandando-lhe dizer que aquela era a moeda que se lavrava em Portugal pera pagar páreas àqueles que as pediam aos lugares e senhorios del-rei Dom Manuel, rei de Portugal e senhor das Índias e do reino de Ormuz. in Fernão Lopes de Castanheda (1554)

Historia do descobrimento e conquista de India pelos Portugueses Volume II, pg.211

^ Carter, Laraine Newhouse (1 January 1991). Persian Gulf States: Chapter 1B. The Gulf During the Medieval Period. Countries of the World. Bureau Development, Inc.

^ Afonso, like many others since then, took office as governor: when appointing the Viceroy Francisco de Almeida, the King promised not to appoint another in his lifetime, a vote of confidence in contradiction with the short term of three years he gave him, that may be due to the great fears about the sharing of power that this position represented.

^ In the first months of 1508, the son of D. Francisco de Almeida, Lourenço de Almeida, died in dramatic circumstances at the Battle of Chaul and there are reports that the viceroy, an enlightened and incorruptible ruler, turned vindictive and cruel.

^ Fernão Lopes de Castanheda (1833). Historia do Descobrimento e Conquista da India pelos Portugueses. Typographia Rollandiana.

^ (Henry Morse Stephens 1897, pp. 61–62)

^ R. S. Whitewayy (1995). The Rise of Portuguese Power in India (1497–1550). p. 126. ISBN 978-81-206-0500-8.

^ Neto, Ricardo Bonalume (1 April 2002). "Lightning rod of Portuguese India". MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History. Cowles Enthusiast Media Spring. p. 68.

^ Neto, Ricardo Bonalume. MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History p. 68. Cowles Enthusiast Media Spring. 1 April 2002 (Page news on 20 October 2006)

^ Almeida returned to Portugal five days later, but died in a skirmish with the Khoikhoi near the Cape of Good Hope.

^ ab Barbara Watson Andaya; Leonard Y. Andaya (1984). A History of Malaysia. Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-312-38121-9.

^ abc Bhagamandala Seetharama Shastry, Charles J. Borges, "Goa-Kanara Portuguese relations, 1498–1763" pp. 34–36

^ Kerr, Robert (1824)

^ Goa Through the Ages: An economic history. 1990. pp. 220–221. ISBN 978-81-7022-226-2.

^ "Commentarios do grande Afonso Dalboquerque", p. 157

^ Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado (1982). Glossário Luso-Asiático. Buske Verlag. p. 382. ISBN 978-3-87118-479-6.

^ Gaspar Correia Lendas da Índia, book II tome II, part I pp.440–441, 1923 Edition

^ Germano de Sousa (2013) História da Medicina Portuguesa Durante a Expansão Circulo de Leitores, Lisbon

^ "Afonso de Albuquerque, the Great | Portuguese conqueror | Britannica.com". britannica.com. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

^ abc Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1300 (2nd Ed.). London: MacMillan. p. 23. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

^ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2007). Historic cities of the Islamic world. BRILL. p. 317. ISBN 978-90-04-15388-2. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

^ Afonso de Albuquerque (1774). Commentarios do grande Afonso Dalboquerque: capitão geral que foi das Indias Orientaes em tempo do muito poderoso rey D. Manuel, o primeiro deste nome. Na Regia Officina Typografica.

^ Teotónio R. de Souza (1985). Indo-Portuguese History: Old Issues, New Questions. Concept Publishing Company. p. 60.

^ Orfas del Rei, literally translated as "Orphans of the King", were Portuguese orphan girls sent to overseas colonies to populate them McDonogh, Gary (2009). Iberian Worlds (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-415-94771-8., 336 pages

^ Sarkissian, Margaret (2000). D'Albuquerque's Children: Performing Tradition in Malaysia's Portuguese Settlement (illustrated ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-226-73498-9., 219 pages

^ Manuel Teixeira, "The Portuguese missions in Malacca and Singapore (1511–1958)", Agência Geral do Ultramar 1963

^ Pires, Tomé (1990). Suma Oriental of Tome Pires – 2 Vols. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0535-0.

^ ab Donald F. Lach (1994). Asia in the Making of Europe. I: The Century of Discovery. University of Chicago Press. pp. 520–521, 571. ISBN 978-0-226-46731-3.

^ A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300

^ Hannard (1991), page 7;Milton, Giles (1999). Nathaniel's Nutmeg. London: Sceptre. pp. 5, 7. ISBN 978-0-340-69676-7.

^ Mote, Frederick W. and Denis Twitchett. (1998). The Cambridge History of China; Volume 7–8. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

ISBN 0-521-24333-5 (Hardback edition). p.340

^ Afonso de Albuquerque Cartas para El-Rei D. Manuel I edited by António Baião (1942). Letter of 1 April 1512

^ Francis Millet Rogers (1962). The Quest for Eastern Christians. University of Minnesota Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8166-0275-9.

^ M. D. D. Newitt (2005). A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400–1668. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-415-23979-0.

^ Andrew James McGregor (2006). A Military History of Modern Egypt: From the Ottoman Conquest to the Ramadan War. Praeger Publishers. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-275-98601-8.

^ Afonso de Albuquerque (1999). The Commentaries of the Great Afonso Dalboquerque, Second Viceroy of India. Elibron Classics. ISBN 978-1-4021-9508-2.

^ Roger Crowley (2016): Conquerors: How Portugal Seized the Indian Ocean and Forges the First Global Empire] p.335

^ Elaine Sanceau (1936). Indies Adventure: The Amazing Career of Afonso de Albuquerque, Captain-general and Governor of India (1509–1515) p.227

^ Bedini, p. 112

^ História do famoso rhinocerus de Albrecht Dürer Archived 18 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine., Projecto Lambe-Lambe (in Portuguese).

^ ab " target="_blank"http://intlhistory.blogspot.com.au/2012/07/alfonso-de-albuquerque-history-figure.html

^ John Holland Rose; Ernest Alfred Benians; Arthur Percival Newton (1928). The Cambridge History of the British Empire. CUP Archive. p. 12.

^ abcd Muchembled, Robert; Monter, William (2007). Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-521-84548-9.

^ ab Albuquerque, Brás de (1774). Commentarios do grande Afonso Dalboquerque, parte IV, pp. 200–206

^ Gaspar Correia (1860) Lendas da Índia, volume II, p 458

^ Rinehart, Robert (1 January 1991). Portugal: Chapter 2B. The Expansion of Portugal. Countries of the World. Bureau Development, Inc.

^ na cidade se aleuantaram grandes prantos... in Gaspar Correia, Lendas da Índia 1860 edition, Typographia da Academia Real das Sciencias, pg. 459

^ Os capitães o leuaram assy assentado na cadeira, posto sobre hum palanquim, que era visto de todo o povo... in Gaspar Correia,Lendas da Índia[permanent dead link] 1860 edition, Typographia da Academia Real das Sciencias, pg. 460

^ This Church was later demolished between 1811 and 1842; see Manoel José Gabriel Saldanha, "História de Goa:(política e arqueológica)", p. 145,

ISBN 81-206-0590-X

^ se ajuntou moltidão do povo com grandes prantos, christãos e gentios... in Gaspar Correia, Lendas da Índia 1860 edition, Typographia da Academia Real das Sciencias, pg. 459

^ ...que dizião que Deos o havia lá mister para guerras e por ysso o leuara ... in Gaspar Correia, Lendas da Índia 1860 edition, Typographia da Academia Real das Sciencias, pg. 459

^ Bibliotheca Lusitana, Diogo Barbosa Machado, Tomo I, p. 23

^ Stier, Hans Erich (1942) Die Welt als Geschichte: Zeitschrift für Universalgeschichte "W. Kohlhammer"

^ Forbes, Jack D. (1993) Africans and Native Americans "University of Illinois Press". 344 pages.

ISBN 0-252-06321-X

^ Albuquerque, Brás, Commentaries, vol VI, p. 198

^ "Alphonso mangoes". Savani Farms. Retrieved 14 July 2006.

^ Lonely Planet Malaysia, Singapore & Brunei by Simon Richmond, Lonely Planet (2010), p. 30

^ [2] Cross-Cultural Alliance-Making and Local Resistance in Maluku during the Revolt of Prince Nuku, 1780–1810, by Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, prof. mr. P. F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op woensdag 12 September 2007 klokke 15.00 uur. p. 11

^ "Papua New Guinea Expedition". Sio.ucsd.edu. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

^ Gordon L. Rottman (2002). World War Two Pacific Island Guide. Greenwood Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-313-31395-0.

^ McKinnon, Rowan; Carillet, Jean-Bernard; Starnes, Dean (2008). Papua New Guinea & Solomon Islands. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-74104-580-2.

^ Historical Dictionary of the Discovery and Exploration of the Pacific Islands, Max Quanchi, John Robson, Scarecrow Press (2005) p. XLIII

^ NEWSLETTER JULY – DECEMBER 2012. Nº11 MACAU SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL CENTRE P.I. MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE, THE MING PORCELAIN BOTTLE OF JORGE ÁLVARES INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM – MACAU: PAST AND PRESENT. p. 10. (online: http://www.cccm.pt/anexos_publicacoes/d20121024230228.pdf)

^ Denis Crispin Twitchett; John King Fairbank (1978). The Cambridge History of China. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-521-24333-9.

^ China and Europe Since 1978: A European Perspective Cambridge University Press (2002) p. 1

^ The Grove Encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art edited by Gerald W. R. Ward. Oxford University Press (2008) p. 37

^ The Biography of Tea by Carrie Gleason, Crabtree Publishing Company (2007) p. 12

^ Hong Kong & Macau, Andrew Stone, Piera Chen, Chung Wah Chow, Lonely Planet (2010) pp. 20, 21

^ Hong Kong & Macau by Jules Brown Rough Guides (2002) p. 195

^ "Tne Portuguese in the Far East". Algarvedailynews.com. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

^ "'Portugal's Discovery in China' – (China Daily)". china.org.cn. 3 February 2005. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

^ "When Portugal Ruled the Seas". Smithsonian Magazine. 1 September 2007. Archived from the original on 25 December 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

^ "'Portugal's Discovery in China' on Display". China.org.cn. 3 February 2005. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

^ Watercraft on World Coins: America and Asia, 1800–2008, Yossi Dotan, Sussex Academic Press (2010) p. 303

^ "Portugal's AGE OF DISCOVERY". Golisbon.com. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

[permanent dead link]

^ "The 10 Greatest Empires in the History of the World | Business Insider Australia". Au.businessinsider.com. 1 October 2011. Archived from the original on|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). Retrieved 18 April 2013.

^ The Bricks of an Empire IMS-1999 585 Years of Portuguese Emigration, Stanley L. Engennan, Joâo César das Neves (December 1996) p. 2

^ Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania, Barbara A. West. Infobase Publishing (2009) p. 800

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

- Crowley, Roger. Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire (2015) online review

Henry Morse Stephens (1897). Albuquerque. Rulers of India series. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1524-3.

Bailey Wallys Diffie; George Davison Winius (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese Empire: 1415–1580. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-0782-2.

António Henrique R. de Oliveira Marques (1976). A History of Portugal. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-08353-9.

M. D. D. Newitt (2005). A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400–1668. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-23980-6.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Albuquerque, Alphonso d'". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Albuquerque, Alphonso d'". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Bandelier, Adolph Francis Alphonse (1907). "Afonzo de Albuquerque". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Bandelier, Adolph Francis Alphonse (1907). "Afonzo de Albuquerque". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

In other languages

Afonso de Albuquerque (1774). Commentarios do grande Afonso Dalboquerque: capitão geral que foi das Indias Orientaes em tempo do muito poderoso rey D. Manuel, o primeiro deste nome. Na Regia Officina Typografica.

- Albuquerque, Afonso de, D. Manuel I, António Baião, [3] "Cartas para el-rei d. Manuel I", Editora Livraria Sá de Costa (1957)

Primary sources

Kerr, Robert (1824). A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels, Arranged in Systematic Order. Edinburgh: William Blackwood. (volume 6, chapter I)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Afonso de Albuquerque. |

[4] Paul Lunde, The coming of the Portuguese, 2006, Saudi Aramco World

| Preceded by Francisco de Almeida | Governor of Portuguese India 1509–1515 | Succeeded by Lopo Soares de Albergaria |