Saint Apollonia

| Saint Apollonia | |

|---|---|

Saint Apollonia, by Francisco de Zurbarán Museum of Louvre, from the Convent of the Order of Our Lady of Mercy and the Redemption of the Captives Discalced of Saint Joseph (Seville). | |

| Virgin & Martyr | |

| Born | 2nd century |

| Died | 249 Alexandria, Egypt |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Coptic Orthodox Church Eastern Orthodox Churches Oriental Orthodox Churches |

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Tongs (sometimes with a tooth in them), depicted holding a cross or martyr's palm or crown |

| Patronage | Dentists; Tooth problems; Elst, Belgium; Ariccia, Italy; Cuccaro Monferrato, Italy |

Saint Apollonia (Coptic: Ϯⲁⲅⲓⲁ Ⲁⲡⲟⲗⲗⲟⲛⲓⲁ) was one of a group of virgin martyrs who suffered in Alexandria during a local uprising against the Christians prior to the persecution of Decius. According to church tradition, her torture included having all of her teeth violently pulled out or shattered. For this reason, she is popularly regarded as the patroness of dentistry and those suffering from toothache or other dental problems. French court painter Jehan Fouquet painted the scene of St. Apollonia's torture in The Martyrdom of St. Apollonia.[1]

Contents

1 Martyrdom

2 Veneration

3 Presence in England

4 References

5 External links

Martyrdom

Torture of Saint Apollonia (1513, Heilsbronn Cathedral, Bavaria).

Ecclesiastical historians have claimed that in the last years of Emperor Philip the Arabian (reigned 244–249), during otherwise undocumented festivities to commemorate the millennium of the founding of Rome (traditionally in 753 BC, putting the date about 248), the fury of the Alexandrian mob rose to a great height, and when one of their poets prophesied a calamity, they committed bloody outrages on the Christians, whom the authorities made no effort to protect.

Dionysius, Bishop of Alexandria (247–265), relates the sufferings of his people in a letter addressed to Fabius, Bishop of Antioch, of which long extracts have been preserved in Eusebius' Historia Ecclesiae.[2] After describing how a Christian man and woman, Metras and Quinta, were seized and killed by the mob, and how the houses of several other Christians were pillaged, Dionysius continues:

At that time Apollonia, parthénos presbytis (mostly likely meaning a deaconess) was held in high esteem. These men seized her also and by repeated blows broke all her teeth. They then erected outside the city gates a pile of soldiers and threatened to burn her alive if she refused to repeat after them impious words (either a blasphemy against Christ, or an invocation of the heathen gods). Given, at her own request, a little freedom, she sprang quickly into the fire and was burned to death.[3]

This brief tale was extended and moralized in Jacobus da Voragine's Golden Legend (c. 1260).

Fresco of Saint Apollonia

(St. Nicholas Church, Stralsund).

Apollonia and a whole group of early martyrs did not await the death they were threatened with, but either to preserve their chastity or because they were confronted with the alternative of renouncing their faith or suffering death, voluntarily embraced the death prepared for them, an action that runs perilously close to suicide, some thought. Augustine of Hippo touches on this question in the first book of The City of God, apropos suicide:

But, they say, during the time of persecution certain holy women plunged into the water with the intention of being swept away by the waves and drowned, and thus preserve their threatened chastity. Although they quitted life in this wise, nevertheless they receive high honour as martyrs in the Catholic Church and their feasts are observed with great ceremony. This is a matter on which I dare not pass judgment lightly. For I know not but that the Church was divinely authorized through trustworthy revelations to honour thus the memory of these Christians. It may be that such is the case. May it not be, too, that these acted in such a manner, not through human caprice but on the command of God, not erroneously but through obedience, as we must believe in the case of Samson? When, however, God gives a command and makes it clearly known, who would account obedience there to a crime or condemn such pious devotion and ready service?"[4]

The narrative of Dionysius does not suggest the slightest reproach as to this act of St. Apollonia; in his eyes she was as much a martyr as the others, and as such she was revered in the Alexandrian Church. In time, her feast was also popular in the West. A later narrative mistakenly duplicated Apollonia, making her a Christian virgin of Rome in the reign of Julian the Apostate, suffering the same dental fate.

Veneration

Reliquary containing a tooth reputedly that of Saint Apollonia, in the Cathedral of Porto, Portugal.

The Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches celebrate the feast day of St. Apollonia on February 9, and she is popularly invoked against the toothache because of the torments she had to endure. She is represented in art with pincers in which a tooth is held.

Saint Apollonia is one of the two patron saints of Catania.

William S. Walsh noted that, though the major part of her relics were preserved in the former church of St. Apollonia at Rome, her head at the Basilica di Santa Maria in Trastevere, her arms at the Basilica di San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, parts of her jaw in St. Basil's, and other relics are in the Jesuit church at Antwerp, in St. Augustine's at Brussels, in the Jesuit church at Mechlin, in St. Cross at Liege, in the treasury of the cathedral of Porto, and in several churches at Cologne.[5] These relics consist in some cases of a solitary tooth or a splinter of bone. In the Middle Ages, objects claimed to be her teeth were sold as toothache cures.

There was a church dedicated to her in Rome, near the Basilica di Santa Maria in Trastevere, but it no longer exists. Only its little square, the Piazza Sant'Apollonia remains. One of the principal train stations of Lisbon is also named for this saint. There is a statue of Saint Apollonia in the church at Locronan, France. The island of Mauritius was originally named Santa Apolónia in her honor in 1507 by Portuguese navigators.[citation needed] A parish church in Eilendorf, a suburb of Aachen, Germany, is named in honor of Saint Apollonia.

The Madonna Della Strada Chapel at Loyola University Chicago contains a stained glass window on the north wall depicting St. Apollonia.[6] The windows along this wall correspond with the colleges of the university at the time the chapel was built. The Loyola University School of Dentistry closed in 1993, but the window in the chapel remains.[7]

Presence in England

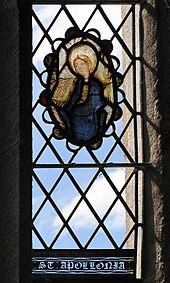

The stained glass image in Kingskerswell church

There are 52 known images of her in various English churches that survived the ravages of the 16th-century Commissioners. These are concentrated in Devon and East Anglia. Most of these images are on the panels of rood screens or featured in stained glass with only one being a stone capital (Stokeinteignhead, Devon). She is also depicted in a tapestry of circa 1499 at St. Mary's Guildhall, Coventry.

By county, some of the locations are:

Cheshire: Bunbury

Cornwall: Poundstock

- Devon: Alphington (now gone), Ashton, Combe Martin, Exeter Cathedral (tapestry in St. Gabriel's chapel), Holne, Kenn, Kenton, Kingskerswell (see photo), Manaton, Payhembury, South Milton, Stoke-in-Teignhead, Torbryan, Ugborough, Whimple (now gone), Widecombe-in-the-Moor, Wolborough (Newton Abbot)

Lincolnshire: Long Sutton

Norfolk: Barton Turf, Docking, Horsham St Faith, Ludham, Norwich (St. Stephen's), Norwich Over the Water (church disused), Sandringham

Suffolk: Norton, Somerleyton, Westhall, Chilton

Her image is the side support of the arms of the British Dental Association.

References

- Attwater, Donald and Catherine Rachel John. The Penguin Dictionary of Saints. 3rd edition. New York: Penguin Books, 1993. .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 0-14-051312-4. - Beal, John F. Representations of St Apollonia in British Churches. Dental Historian vol 30, pp 3–19, (1996).

"Santa Apolonia, Patrona De Odontólogos y Enfermedades Dentales" [Santa Apolonia, Patron of Dentists and Dental Diseases] (in Spanish). Dental World. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

^ Olmert, Michael (1996). Milton's Teeth and Ovid's Umbrella: Curiouser & Curiouser Adventures in History, p.66. Simon & Schuster, New York.

ISBN 0-684-80164-7.

^ Eusebius of Caesarea, Historia Ecclesiae, I:vi: 41.

^ "St. Apollonia". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

^ Augustine of Hippo, The City of God, I:26.

^ William S. Walsh, Curiosities of Popular Customs And of Rites, Ceremonies, Observances, and Miscellaneous Antiquities, 1897.

^ The North Wall Stained Glass Windows Loyola University Chicago. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

^ "Loyola Closing Dental School". Chicago Tribune. 9 June 1992. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

External links

Media related to Saint Apollonia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Saint Apollonia at Wikimedia Commons- Colonnade Statue St Peter's Square