Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class cruiser

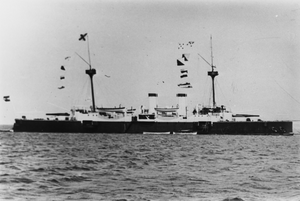

Kaiser Franz Joseph I at anchor | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class |

| Builders: |

|

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | None |

| Succeeded by: | Zenta-class |

| Cost: | 5,360,000 Guldens or 10,720,000 Krone (entire class)[a] |

| Built: | 1888–1890 |

In commission: | 1890–1917 |

| Planned: | 3 |

| Completed: | 2 |

| Cancelled: | 1 |

| Lost: | 2 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Type: | Protected cruiser[b] |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 14.75–14.8 m (48 ft 5 in–48 ft 7 in)[d] |

| Draught: | 5.7 m (18 ft 8 in) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 19.65–20.00 knots (36.39–37.04 km/h; 22.61–23.02 mph) |

| Range: | 3,200 nautical miles (5,900 km; 3,700 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 367 or 427-444[f] |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

| General characteristics (after modernization) | |

| Armament: |

|

The Kaiser Franz Joseph I class (sometimes called the Kaiser Franz Josef I class[1]) was a class of two protected cruisers built for the Austro-Hungarian Navy. Named for Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph I, the class comprised SMS Kaiser Franz Joseph I and SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth. Construction took place throughout the late 1880s, with both ships being laid down in 1888. Kaiser Franz Joseph I was built by Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino in Trieste, while Kaiserin Elisabeth was built at the Pola Navy Yard in Pola. The Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class ships were the first protected cruisers constructed by the Austro-Hungarian Navy.[b]Kaiser Franz Joseph I was the first ship of the class to be commissioned into the fleet in July 1890. She was followed by Kaiserin Elisabeth in November 1892.

Constructed in response to the Italian cruisers Giovanni Bausan and Etna, the design of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class was heavily influenced by the Jeune École (Young School) naval strategy. The cruisers were intended to serve as the "battleship of the future" by Commander-in-Chief of the Navy (German: Marinekommandant) Maximilian Daublebsky von Sterneck, the ships were heavily criticized by officers and sailors alike in the Austro-Hungarian Navy, who labeled the ships, "Sterneck's sardine–boxes". Changes in technology and strategic thinking around the world rendered the design of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class ships obsolete shortly after they were commissioned. Nevertheless, the ships remained an important component of Austro-Hungarian naval policy, which continued to emphasize the Jeune École doctrine and the importance of coastal defense and overseas missions to show the flag around the world. Both Kaiser Franz Joseph I and Kaiserin Elisabeth participated in several overseas voyages during their careers, with the former conducting a tour of East Asia between 1892 and 1893, the first such voyage by a steel-hulled ship of the Austro-Hungarian Navy. Archduke Franz Ferdinand accompanied Kaiserin Elisabeth for most of this voyage. Kaiserin Elisabeth saw action during the Boxer Rebellion, and thereafter the two ships of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class would alternate tours of duty in the Far East until the start of World War I.

At the outbreak of the war, Kaiserin Elisabeth was stationed in China and participated in the defense of the German-held Kiautschou Bay concession against Japan and the United Kingdom. Her guns were removed during the Siege of Tsingtao for use as a shoreline battery. She was scuttled by her crew in November 1914 shortly before the surrender of the port of Tsingtao to Anglo-Japanese forces. Kaiser Franz Joseph I was a member of the Fifth Battle Division at the onset of war and was stationed at the Austro-Hungarian naval base at Cattaro. Obsolete by the start of the war, Kaiser Franz Joseph I saw little action during most of the conflict, and rarely left the Bocche di Cattaro. In late 1914, she participated in shelling Franco-Montenegrin artillery batteries located on the slopes of Mount Lovćen, which overshadowed the Bocche. In January 1916, when the Austria-Hungary began an invasion of Montenegro, Kaiser Franz Joseph I assisted in again silencing the Montenegrin batteries on Mount Lovćen in support of the Austro-Hungarian Army, which seized the mountain and subsequently captured the Montenegrin capital of Cetinje, knocking the country out of the war.

In 1917, Kaiser Franz Joseph I was decommissioned, disarmed, and converted into a headquarters ship for the Austro-Hungarian base at Cattaro. She remained in this capacity through the rest of the war. When Austria-Hungary was facing defeat in October 1918, the Austrian government transferred its navy to the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs in order to avoid having to hand the ship over to the Allies. Following the Armistice of Villa Giusti in November 1918, an Allied fleet sailed into Cattaro and seized the former Austro-Hungarian ships stationed in the Bocche, including Kaiser Franz Joseph I. She was ceded to France as a war reparation after the war, but sank during a gale off Kumbor in October 1919.

Contents

1 Background

1.1 Emergence of Jeune École

1.2 Proposals and budget

2 Design

2.1 General characteristics

2.2 Propulsion

2.3 Armament

2.4 Armor

3 Ships

4 Service history

4.1 Pre-war

4.1.1 Franz Ferdinand's circumnavigation of the world

4.1.2 1895-1914

4.2 World War I

4.2.1 Siege of Tsingtao

4.2.2 1916-1918

4.2.3 Cattaro Mutiny

4.2.4 End of the war

4.3 Post-war

5 Notes

6 Citations

7 References

8 Further reading

Background

On 13 November 1883, Emperor Franz Joseph I promoted Maximilian Daublebsky von Sterneck to the office of vice admiral, and named him Marinekommandant of the Austro-Hungarian Navy as well as Chief of the Naval Section of the War Ministry (German: Chef der Marinesektion).[2] Sterneck's presence at the Battle of Lissa, and his past ties to Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, led to his promotion being widely supported within the Navy. After spending the first several years as Marinekommandant reforming the administrative bureaucracy of the Navy, Sterneck began to pursue a new program of warship construction in the late 1880s and early 1890s.[3]

Emergence of Jeune École

A map of Austria-Hungary and the Adriatic Sea in 1899

In the 1880s, the naval philosophy of Jeune École began to gain prominence among smaller navies throughout Europe, particularly within the French Navy, where it was first developed by naval theorists wishing to counter the strength of the British Royal Navy. Jeune École advocated the use of a powerful armed fleet primarily made up of cruisers, destroyers, and torpedo boats to combat a larger fleet made up of ironclads and battleships, as well as disrupt the enemy's global trade.[4]Jeune École was quickly adopted as the main naval strategy for Austria-Hungary under the leadership of Sterneck.[5] His strong support for Jeune École was rooted in a belief that the strategy appeared to fit existing Austro-Hungarian naval policy, which stressed coastal defense and limited power projection beyond the Adriatic Sea. Tests conducted by the Austro-Hungarian Navy during the early and mid 1880s led Sterneck to believe that torpedo boat attacks against a fleet of battleships, a central component of Jeune École, would have to be supported by larger ships such as cruisers. As Austria-Hungary lacked the ability to disrupt global trade due to its location in the Adriatic Sea, and the two potential enemies the Navy could find itself at war with–Italy and Russia–lacked suitable targets for commerce raiding or overseas colonies, the cruisers which would be designed under the principles of Jeune École would instead focus on coastal defense and leading torpedo boat flotillas as opposed to commerce raiding. These tests, as well as the adoption of Jeune École as the principal naval strategy of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, led to the development of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class cruisers.[6]

Proposals and budget

Under the Navy's 1881 plan which was passed by his predecessor, Friedrich von Pöck, Sterneck proposed the construction of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class cruisers to the Austrian and Hungarian Delegations for Common Affairs as "replacements" for the Austro-Hungarian ironclads Lissa and Kaiser.[7][h]Kaiser had not seen active service since 1875 and Pöck had intended to have her replaced prior to his resignation in 1883. Lissa had been re-assigned to the II Reserve by 1888.[8] The Delegations strongly supported the proposal for the cruisers, in large part due to their relatively low price compared to other capital ships of the era.[9] Both Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class cruisers were to cost 5,360,000 Guldens or 10,720,000 Krone,[a] while the ironclad warship Kronprinz Erzherzog Rudolf, laid down in 1884, had cost 5,440,000 Guldens to construct.[7] The Delegations thus allocated funding to construct two Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class ships—"Ram Cruiser A" and "Ram Cruiser B" (German: "Rammkreuzer A" and "Rammkreuzer B")—under the 1888 and 1889 budgets.[10]

Sterneck was inspired to propose the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class after the construction of the Italian cruisers Giovanni Bausan and Etna,[11] but this early enthusiasm was tempered by concerns that the ships would be unable to match larger battleships of foreign nations, which were beginning to approach 10,000 metric tons (9,800 long tons; 11,000 short tons). In 1889, the Austro-Hungarian Ministerial Council advocated that the third proposed ship of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class be postponed. While the initial funds for "Rammkreuzer C" were still included in the 1890 naval budget, authorization for the ship's construction was never given by the Delegations and the ship was never laid down.[7]

Design

A depiction of Kaiserin Elisabeth shortly after her commissioning into the Austro-Hungarian Navy

Authorized near the start of Austria-Hungary's second naval arms race against Italy, the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class cruisers were designed to lead torpedo flotillas into battle against a larger fleet of battleships.[12] While Italy and Austria-Hungary had become allies under the 1882 Triple Alliance, Italy's Regia Marina remained the most-important naval power in the region which Austria-Hungary measured itself against, often unfavorably. Despite achieving victory at sea after the Battle of Lissa during the Third War of Italian Independence, Italy still possessed a larger navy than Austria-Hungary in the years following the war. The disparity between the Austro-Hungarian and Italian navies had existed ever since the Austro-Italian ironclad arms race of the 1860s. While Austria-Hungary had shrunk the disparity in naval strength throughout the 1870s, Italy boasted the third-largest fleet in the world by the late 1880s, behind the French Navy and the British Royal Navy.[13]

Sterneck hailed the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class cruisers as the "battleships of the future", and it was envisioned that the ships would lead a torpedo division made up of the light cruisers Leopard and Panther, two destroyers, and 12 torpedo boats. The displacement and speed of the ships illustrated Austria-Hungary's application of Jeune École, while the prominent ram bows of the cruisers reflected the legacy of the Battle of Lissa, which saw a much smaller Austrian fleet defeat the Italian Regia Marina using ramming tactics. Sterneck also believed that the cruisers would operate in chaotic melee engagements alongside the torpedo division they would lead, which would necessitate a bow ram in order to damage and sink enemy vessels similar to what Tegetthoff had done at Lissa. The large guns of the cruisers were also chosen in order to give credence to Sterneck's plan for the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class ships to replace heavily armored ironclads and battleships. Sterneck hailed the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class cruisers as the "battleships of the future".[14]

General characteristics

Designed by Chief Engineer Franz Freiherr Jüptner,[15] the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class ships had an overall length of 103.7–103.9 meters (340 ft 3 in–340 ft 11 in) and a length between perpendiculars of 97.9 meters (321 ft 2 in).[c] They had a beam of 14.75–14.8 meters (48 ft 5 in–48 ft 7 in),[d] and a mean draft of 5.7 meters (18 ft 8 in) at deep load. They were designed to displace 3,967 metric tons (3,904 long tons; 4,373 short tons) at normal load, but at full combat load they displaced 4,494 metric tons (4,423 long tons; 4,954 short tons).[16][17]

Propulsion

Both ships possessed two shafts which operated two screw propellers measuring 4.35 meters (14 ft 3 in) in diameter.[18] These propellers were powered by two sets of horizontal triple expansion engines, that were designed to provide 8,000–8,450 shaft horsepower (5,970–6,300 kW).[e] The propulsion systems of both ships also consisted of four cylindrical double-ended boilers, which gave the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class ships a top speed of 19.65–20.00 knots (36.39–37.04 km/h; 22.61–23.02 mph). Both ships carried 670 metric tons (660 long tons; 740 short tons) of coal had a range of approximately 3,200 nautical miles (5,900 km; 3,700 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), and were manned by a crew of 367 to 444 officers and men.[16][18][17][f]

Armament

A line drawing of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class cruisers

The Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class cruisers had an armament system which was based heavily on the design of "Elswick cruisers" such as the Chilean cruiser Esmeralda.[12] They were armed with a main battery of two 24 cm (9.4 in) K L/35 Krupp guns, mounted in turrets fore and aft. The ships' secondary armament consisted of six 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/35 guns, mounted in casemates amidships with three on either side. Both ships also possessed 16 47 mm (1.9 in) SFK L/44 guns, and four 40–45 cm (16–18 in) torpedo tubes with two located at the bow and stern, and two located amidships.[16][g] These heavy guns were intended to help the cruisers open fire on heavier battleships from a distance while supporting torpedo boat attacks on an enemy warship or fleet.[14][12] Between 1905 and 1906, while the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class ships were undergoing a refit for modernization, their main batteries were replaced by two 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/40 Škoda guns.[19]

The mountings the main guns were located on was made up of a rotating platform and a domed gun turret. These mountings were operated by a series of steam pumps below the deck of both ships. While each turret had its own steam pump, pipes ran the length of the ship to connect each steam pump and their accompanying turret together in order to provide a backup system. The maximum elevation of the two main guns, as well as their loading angle, was 13.5°. When at this angle, the range of the main guns' 215 kilograms (474 lb) shells was 10,000 meters (390,000 in). The maximum elevation of the ships' secondary armament was 16°, and their 21 kilograms (46 lb) shells had the same range as the main battery.[20]

Armor

The Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class cruisers were protected at the waterline with an armored belt which measured 57 mm (2.2 in) thick amidships. The turrets had 90 mm (3.5 in) thick armor, while the thickness of the deck armor for both ships was 38 mm (1.5 in). The conning tower was protected by 50–90 mm (2.0–3.5 in) armor.[1][17] The machinery for the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class was assembled at Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino, and both ships were constructed with a double-bottom hull and designed with over 100 watertight compartments. The steam-powered pumps used to control flooding aboard each ship could discharge 1,200 metric tons (1,200 long tons; 1,300 short tons) of water per hour.[18]

The defensive systems of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class ships also consisted of coal bunkers located abreast the boiler rooms of both ships, and a horizontal cofferdam located at the ships' waterline, which was filled with cellulose fiber. The fiber was intended to seal up any holes in the ships from artillery rounds by swelling up upon contact with seawater, while the impacting shell itself would be slowed down by the surrounding coal, which would also serve to contain any explosions.[12]

Ships

| Name | Namesake | Builder | Laid down | Launched | Commissioned | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kaiser Franz Joseph I | Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria | Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino, Trieste | 3 January 1888 | 18 May 1889 | 2 July 1890 | Ceded to France after World War I, sank during a gale off of Kumbor in the Bocche di Cattaro on 17 October 1919 |

Kaiserin Elisabeth | Empress Elisabeth of Austria | Pola Navy Yard, Pola | July 1888 | 25 September 1890 | 24 November 1892 | Scuttled in Jiaozhou Bay on 2 November 1914 |

| "Ram Cruiser C" (German: "Rammkreuzer C")[h] | — | — | — | — | — | Never laid down. Redesigned to become the armored cruiser Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia |

Service history

Kaiserin Elisabeth conducting sea trials. Note the temporary rig located at the bridge of the ship

The first ship of the class, "Ram Cruiser A",[12] was formally laid down by Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino at Trieste on 3 January 1888. Two months later, "Ram Cruiser B" was laid down at the Pola Navy Yard in July. Kaiser Franz Joseph I would be the first ship of the class to be named when she was launched at Trieste on 18 May 1889. She was followed by Kaiserin Elisabeth on 25 September 1890. After conducting sea trials, Kaiser Franz Joseph I was commissioned into the Austro-Hungarian Navy on 2 July 1890, while Kaiserin Elisabeth followed two years later on 24 November 1892.[17][21] A planned third cruiser, designed "Ram Cruiser C", was never constructed as a member of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class. Her design instead underwent modifications to address the changing technological and strategic outlook of naval warfare in the 1890s which had begun to render the concept of Jeune École obsolete. These changes eventually manifested themselves in the armored cruiser Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia.[22]

Pre-war

Changes in both technology as well as naval doctrine would render the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class ships obsolete shortly after their commissioning. The rapid decline of Jeune Ecole during the 1890s and 1900s soon rendered the concept of "ram cruisers" obsolete. Their thin armor, slow speed, and slow-firing guns led to Sterneck's "battleships of the future" being labeled as "tin cans" and "Sterneck's sardine–boxes" by Austro-Hungarian sailors and naval officers.[7][23][10][24] Indeed, Sterneck's 1891 fleet plan was rejected on the grounds that "ram cruisers" were too large, expensive, and heavy in size to properly carry out the missions Sterneck envisioned them for. Sterneck continued to support the concept of torpedo ram cruisers rest of his tenure as Marinekommandant, but his death in December 1897 marked the end of Austria-Hungary's application of Jeune Ecole.[25][24] The failure of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class thus contributed to the Austro-Hungarian Navy's decision to transition away from cruisers to battleships as the primary capital ship of the Navy, and in 1899 the first Habsburg-class battleships were laid down.[24]

Despite these shortcomings, the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class ships would both have long careers within the Austro-Hungarian Navy, and both would conduct numerous voyages.[24] In the summer of 1890, German Kaiser Wilhelm II invited Sterneck to participate in German exercises in the Baltic Sea. Kaiser Franz Joseph I was dispatched along with Kronprinz Erzherzog Rudolf and Kronprinzessin Erzherzogin Stephanie to represent the Austro-Hungarian Navy. While under the command of Rear Admiral Johann von Hinke, Kaiser Franz Joseph I visited Gibraltar and Cowes in the United Kingdom, where Queen Victoria reviewed the Austro-Hungarian fleet. The cruiser also made port in Copenhagen, Denmark, and Karlskrona, Sweden, before joining the German Imperial Navy in the Baltic for its summer exercises. On the return voyage, Kaiser Franz Joseph I made port in France, Portugal, Spain, Italy, and British Malta before returning to Austria-Hungary.[26][24]

Kaiserin Elisabeth on 8 December 1892, as she prepares for a voyage to the Far East with Archduke Franz Ferdinand aboard

Kaiserin Elisabeth also participated in overseas voyages during this time. In December 1892, Archduke Franz Ferdinand boarded the cruiser in Trieste for a tour of East Asia and the Pacific Ocean. Commanded by Captain Alois von Becker and a host of officers which included Archduke Leopold Ferdinand of Austria, Kaiserin Elisabeth sailed through the Adriatic Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean before entering the Suez Canal. She made port in British Ceylon, and then Bombay, where Franz Ferdinand and his party made landfall for a tour of the British Raj. Kaiserin Elisabeth subsequently sailed around the Indian subcontinent to retrieve the Archduke at Calcutta. From Calcutta, the voyage resumed through the Dutch East Indies before reaching Sydney. There, the Archduke once again departed for a hunting tour of the Australian Outback. The trip continued from Sydney through Nouméa, New Hebrides, the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, Sarawak, Hong Kong and finally Japan, where Kaiserin Elisabeth and Franz Ferdinand departed ways. The Archduke would eventually find his way back to Austria-Hungary after crossing the Pacific Ocean aboard RMS Empress of China from Yokohama to Vancouver. He then traveled through North America by train before crossing the Atlantic Ocean aboard a French steam ship, and arrived back in Trieste from Le Harve in October 1893, completing a circumnavigation of the world. Kaiserin Elisabeth continued her voyage from Japan, showing the Austro-Hungarian flag in the waters off China and Southeast Asia before returning to Trieste via the Suez Canal in 1893.[27]

Franz Ferdinand later recalled his voyage aboard Kaiserin Elisabeth to be among the fondest memories of his circumnavigation of the world. The Archduke recalled the "agreeable circle of officers" he encountered aboard Kaiserin Elisabeth, and praised the sailors of the vessel, particularly the Germans and Croatians. Franz Ferdinand went so far as to write that his time aboard the cruiser made him feel like a "member of a great family". Naval historian Lawrence Sondhaus writes that this voyage aboard Kaiserin Elisabeth cemented both Franz Ferdinand's support for the reform of Austria-Hungary into a federalized state, as well as his commitment to expanding the Austro-Hungarian Navy and transforming it into a naval force befitting a Great Power.[28]

1895-1914

Kaiserin Elisabeth in Pola on 1 October 1901 after her return from the Boxer Rebellion.

In 1895, both Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class cruisers participated in the opening ceremony of the Kiel Canal.[29] Thereafter, Kaiserin Elisabeth sailed to the Levant on her return trip back to Austria-Hungary, returning in 1896. In 1897, Kaiser Franz Joseph I sailed to the Far East, and returned later that year to participate in an international demonstration off the coast of Crete. The following year, she participated in celebrations honoring Vasco de Gama in Lisbon, Portugal. In 1899, Kaiserin Elisabeth conducted her second voyage to the Far East, and the third such trip of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class, as part of Austria-Hungary's contributions to putting down the Boxer Rebellion in China.[30]

On 27 December 1902, Austria-Hungary was granted a concession in Tianjin as part of its contributions to the Eight-Nation Alliance which had put down the Boxer Rebellion. It was decided after the rebellion that the Austro-Hungarian Navy would maintain a permanent presence in the Far East to guard Austro-Hungarian interests in China, as well as provide protection for the Austro-Hungarian concession in Tianjin. Kaiserin Elisabeth was thus stationed in China following the end of the Boxer Rebellion, while Kaiser Franz Joseph I conducted training exercises in the Mediterranean Sea throughout 1903 and 1904.[31] In 1905, she was modernized to have their Krupp guns replaced with 15 centimeters (5.9 in) Škoda guns. These guns were considered more modern than their predecessors, and had a faster loading time. Other changes included moving the location of the secondary guns to the upper deck, where they would be less exposed to the elements and have a better vantage points compared to their previous location in casemates located close to the waterline of both ships.[24] Later that same year, she then sailed for China to relieve Kaiserin Elisabeth, who underwent the same modernization upon her return to Austria-Hungary in 1906.[32]

Kaiser Franz Joseph would remain stationed in China until 1908, while Kaiserin Elisabeth conducted yearly training exercises in the Mediterranean.[31] In 1908, both ships were re-classified as 2nd class cruisers as Kaiserin Elisabeth and Kaiser Franz Joseph I rotated duties, with the former being sent back to China and the later being transferred to Austria-Hungary to serve as a training vessel.[33] In 1911, the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class ships were re-designated as small cruisers.[24] That same year, Kaiserin Elisabeth returned to Austria-Hungary for the last time, while Kaiser Franz Joseph began her final deployment to China. During this period, Kaiserin Elisabeth was mobilized twice during the Balkan Wars, while Kaiser Franz Joseph's crew were deployed to protect Shanghai during the Xinhai Revolution.[34] In 1913, the cruisers were ordered to rotate duties one final time, with Kaiserin Elisabeth going to China, and Kaiser Franz Joseph I returning to Austria-Hungary in 1914.[31]

World War I

Kaiser Franz Joseph I underway

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June 1914 in Sarajevo triggered a chain of events which led to the July Crisis and Austria-Hungary's subsequent declaration of war on Serbia on 28 July. Events unfolded rapidly in the ensuing days. On 30 July 1914 Russia declared full mobilization in response to Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Serbia. Austria-Hungary declared full mobilization the next day. On 1 August both Germany and France ordered full mobilization and Germany declared war on Russia in support of Austria-Hungary. While relations between Austria-Hungary and Italy had improved greatly in the two years following the 1912 renewal of the Triple Alliance,[35] increased Austro-Hungarian naval spending, political disputes over influence in Albania, and Italian concerns over the potential annexation of land in the Kingdom of Montenegro caused the relationship between the two allies to falter in the months leading up to the war. Italy declared neutrality on 1 August, citing Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Serbia as an act of aggression, which was not covered under the Triple Alliance.[36]

By 4 August Germany had already occupied Luxembourg and invaded Belgium after declaring war on France, and the United Kingdom had declared war on Germany in support of Belgian neutrality.[37] Following France and Britain's declarations of war on Austria-Hungary on 11 and 12 August respectively, the French Admiral Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère was issued orders to close off Austro-Hungarian shipping at the entrance to the Adriatic Sea and to engage any Austro-Hungarian ships his Anglo-French fleet came across. Lapeyrère chose to attack the Austro-Hungarian ships blockading Montenegro. The ensuing Battle of Antivari ended Austria-Hungary's blockade, and effectively placed the Strait of Otranto firmly in the hands of Britain and France.[38][39] At the start of the war, Kaiser Franz Joseph I was assigned to the Fifth Battle Division, alongside the three Monarch-class coastal defense ships, and the cruiser Panther at the Austro-Hungarian naval base at Cattaro. Rear Admiral Richard von Barry was assigned command of this division, which was tasked with coastal defense roles.[40] After the loss of the cruiser Zenta at the Battle of Antivari, Austro-Hungarian Marinekommandant Anton Haus blamed Barry for failing to intercept the French forces and relived him of command in October 1914, replacing him with Rear Admiral Alexander Hansa.[41]

Kaiser Franz Joseph I served as a harbor defense ship for most of the remainder of the war,[11] though she did see action against Montenegrin batteries atop Mount Lovćen, which overshadowed the Bocche di Cattaro, where she was stationed. In September 1914, a French landing party of 140 men assisted Montenegrin troops in installing eight heavy artillery pieces on the slopes of Mount Lovćen. This bolstered the artillery Montenegro had already placed on the mountain, and posed a major threat to the Austro-Hungarian base located at Cattaro. Throughout September and October, the Austro-Hungarian Fifth Division and the Franco-Montenegrin artillery dueled for control over the Bocche. The arrival of the Austro-Hungarian Radetzky-class battleships knocked out two of the French guns and forced the remainder to withdraw beyond the range of the Austro-Hungarian guns. In late November, the French withdrew and handed the guns over to Montenegro to maintain.[42]

Siege of Tsingtao

Kaiserin Elisabeth was to be the only Austro-Hungarian warship caught outside of the Adriatic at the onset of the war, save the yacht Taurus, which managed to evade contact with the Allies during her voyage back to Austria-Hungary from Constantinople.[40] As she was too slow to conduct commerce raiding operations in the Pacific against British and French shipping, she sailed for the German-held Kiautschou Bay concession, before making port at Tsingtao where she reinforced Germany's East Asia Squadron. Japan's declaration of war on Germany and Austria-Hungary on 23 and 25 August respectively, sealed the fate of Germany's Asian and Pacific possessions, and the Austro-Hungarian cruiser. Austria-Hungary had hoped to disarm and intern the ship in Shanghai, with the intentions of having China return the vessel after the successful conclusion of the war, but German Kaiser Wilhelm II personally ordered his Austro-Hungarian allies to place the ship under the command of the German forces defending Kiautschou Bay.[43]

Kaiserin Elisabeth at anchor

Japan quickly laid siege to the German possession. On 6 September, the first air-sea battle in history took place when a Farman seaplane launched by the Japanese seaplane carrier Wakamiya unsuccessfully attacked the Kaiserin Elisabeth and the German gunboat Jaguar in Qiaozhou Bay with bombs.[44] Early in the siege, Kaiserin Elisabeth and Jaguar made an unsuccessful sortie against Japanese vessels blockading Tsingtao. Later, Kaiserin Elisabeth's guns were removed from the ship and mounted on shore, creating the "Batterie Elisabeth". Her crew meanwhile took part in the defense of Tsingtao, led by Captain Richárd Makovicz. As the siege progressed, the German and Austro-Hungarian naval vessels trapped in the harbor were scuttled to avoid their capture by the British and Japanese. Kaiserin Elisabeth would be the second to last ship scuttled, sinking on 2 or 3 November.[45][46][i] She was followed by Jaguar on 7 November, the day the German and Austro-Hungarian forces surrendered Tsingtao to the Allies. During the fighting, ten of Kaiserin Elisabeth's crew were killed.[45]

The nearly 400-man crew, along with Makovicz, were taken prisoner by the Japanese, where they spent the remainder of the war spread out among five separate prisoner of war camps in Japan. After the end of the war, the Italians were allowed to return home first, followed by the remaining ethnic groups which made up the cruiser's former crew. In December 1919, Captain Makovicz left Kobe, Japan, with the final group of Austrian and German naval prisoners. They reached Wilhelmshaven, Germany, in February 1920, with Makovicz and his men arriving in Salzburg, Austria, in March, as the last prisoners of war of the Austro-Hungarian Navy to return home.[47]

1916-1918

In late 1915, it was decided by Austria-Hungary and Germany that after finally conquering Serbia, Montenegro would be knocked out of the war next. On 8 January 1916, Kaiser Franz Joseph I and the other ships of the Fifth Division began a barrage which would last three days against the Montenegrin fortifications on Mount Lovćen. The sustained artillery bombardment allowed the Austro-Hungarian XIX Army Corps to capture the mountain on 11 January. Two days later, Austro-Hungarian forces entered Montenegro's capital of Cetinje, knocking Montenegro out of the war.[48][49] After the conquest of Montenegro, Kaiser Franz Joseph I remained at anchor in the Bocce di Cattaro for the remainder of the war. She almost never ventured outside of Cattaro for the next two years.[50]

Cattaro Mutiny

Kaiser Franz Joseph I at anchor in Cattaro during World War I

By early 1918, the long periods of inactivity had begun to wear on the crews of several Austro-Hungarian ships at Cattaro, primarily those of ships which saw little combat. On 1 February, the Cattaro Mutiny broke out, starting aboard Sankt Georg. The mutineers rapidly gained control of most of the warships in the harbor, while others such as Kaiser Franz Joseph I flew the red flag despite remaining neutral in the rebellion.[51][52] The crews of the cruisers Novara and Helgoland resisted the mutiny,[53] with the latter preparing their ship's torpedoes but rebels aboard the cruiser Sankt Georg aimed their 24 cm (9.4 in) guns at Helgoland, forcing them to back down. Novara's commander, Johannes, Prinz von Liechtenstein, initially refused to allow a rebel party to board his vessel, but after the rebel-held cruiser Kaiser Karl VI trained her guns on Novara, he relented and let the crew fly a red flag in support of the mutiny. Liechtenstein and Erich von Heyssler, the commander of Helgoland, discussed overnight how to extricate their vessels, their crews having abstained from actively supporting the rebels.[54]

The following day, many of the mutinous ships abandoned the effort and rejoined loyalist forces in the inner harbor after shore batteries loyal to the Austro-Hungarian government opened fire on the rebel-held Kronprinz Erzherzog Rudolf. Liechtenstein tore down the red flag before ordering his ship to escape into the inner harbor; they were joined by the other scout cruisers and most of the torpedo boats, followed by several of the other larger vessels. There, they were protected by shore batteries that opposed the mutiny. By late in the day, only the men aboard Sankt Georg and a handful of destroyers and torpedo boats remained in rebellion. The next morning, the Erzherzog Karl-class battleships arrived from Pola and put down the uprising.[55][56] In the immediate aftermath of the mutiny, Kaiser Franz Joseph I's complement was reduced to a caretaker crew while the cruiser was converted into a barracks ship. Her guns were also removed for use on the mainland.[51]

After the Cattaro Mutiny, Admiral Maximilian Njegovan was fired as Commander-in-Chief (German: Flottenkommandant) of the Navy, though at Njegovan's request it was announced that he was retiring.[57]Miklós Horthy, who had since been promoted to commander of the battleship Prinz Eugen, was promoted to rear admiral and named as the Flottenkommandant of the Austro-Hungarian Navy.[58]

End of the war

Kaiser Franz Joseph I at anchor

By October 1918 it had become clear that Austria-Hungary was facing defeat in the war. With various attempts to quell nationalist sentiments failing, Emperor Karl I decided to sever Austria-Hungary's alliance with Germany and appeal to the Allied Powers in an attempt to preserve the empire from complete collapse. On 26 October Austria-Hungary informed Germany that their alliance was over. At the same time, the Austro-Hungarian Navy was in the process of tearing itself apart along ethnic and nationalist lines. Horthy was informed on the morning of 28 October that an armistice was imminent, and used this news to maintain order and prevent another mutiny among the fleet.[59]

On 29 October the National Council in Zagreb announced Croatia's dynastic ties to Hungary had come to a formal conclusion. The National Council also called for Croatia and Dalmatia to be unified, with Slovene and Bosnian organizations pledging their loyalty to the newly formed government. This new provisional government, while throwing off Hungarian rule, had not yet declared independence from Austria-Hungary. Thus Emperor Karl I's government in Vienna asked the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs for help maintaining the fleet and keeping order among the navy. The National Council refused to assist unless the Austro-Hungarian Navy was first placed under its command.[60] Emperor Karl I, still attempting to save the Empire from collapse, agreed to the transfer, provided that the other "nations" which made up Austria-Hungary would be able to claim their fair share of the value of the fleet at a later time.[61] All sailors not of Slovene, Croatian, Bosnian, or Serbian background were placed on leave for the time being, while the officers were given the choice of joining the new navy or retiring.[61][62]

The Austro-Hungarian government thus decided to hand over the bulk of its fleet to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs without a shot being fired. This was considered preferential to handing the fleet to the Allies, as the new state had declared its neutrality. Furthermore, the newly formed state had also not yet publicly dethroned Emperor Karl I, keeping the possibility of reforming the Empire into a triple monarchy alive. The transfer to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs began on the morning of 31 October, with Horthy meeting representatives from the South Slav nationalities aboard his flagship, Viribus Unitis in Pola. After "short and cool" negotiations, the arrangements were settled and the handover was completed that afternoon. The Austro-Hungarian Naval Ensign was struck from Viribus Unitis, and was followed by the remaining ships in the harbor.[63] Control over the battleship, and the head of the newly-established navy for the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, fell to Captain Janko Vuković, who was raised to the rank of admiral and took over Horthy's old responsibilities as Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet.[64][62][65]

Post-war

Kaiser Franz Joseph I sinking during the storm off Cattaro

Despite the transfer, on 3 November 1918 the Austro-Hungarian government signed the Armistice of Villa Giusti with Italy, ending the fighting along the Italian Front.[66] The Armistice of Villa Giusti refused to recognize the transfer of Austria-Hungary's warships to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. As a result, on 4 November 1918, Italian ships sailed into the ports of Trieste, Pola, and Fiume. On 5 November, Italian troops occupied the naval installations at Pola. While the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs attempted to hold onto their ships, they lacked the men and officers to do so as most sailors who were not South Slavs had already gone home. The National Council did not order any men to resist the Italians, but they also condemned Italy's actions as illegitimate. On 9 November, Italian, British, and French ships sailed into Cattaro and seized the remaining Austro-Hungarian ships, including Kaiser Franz Joseph I, which had been turned over to the National Council. At a conference at Corfu, the Allied Powers agreed the transfer of Austria-Hungary's Navy to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs could not be accepted, despite sympathy from the United Kingdom. Faced with the prospect of being given an ultimatum to hand over the former Austro-Hungarian warships, the National Council agreed to hand over all the ships transferred to them by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to include Kaiser Franz Joseph I, beginning on 10 November 1918.[67]

While Cattaro remained under Allied occupation after the war, Kaiser Franz Joseph I remained under the administration of France as it would not be until 1920 when the final distribution of the ships was settled among the Allied powers under the terms of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. While under French control, she was converted into an ammunition ship. On 17 October 1919, she sank while moored in the Bocche di Cattaro during a heavy gale. Her sinking was attributed to several open hatches and her top-heaviness due to the ammunition stored aboard.[32] In 1922, a Dutch salvage company discovered the Kaiser Franz Joseph I and began salvaging operations. Some of her fittings, including her deck cranes, were ultimately salvaged, though most of the ship remained intact at the bottom of the bay. In 1967, the Yugoslav salvage company Brodospas salvaged the wreck as well.[32]

Notes

^ ab In 1892, Austria-Hungary switched its currency from Gulden to Krone, with an exchange rate of 1 Gulden to 2 Krone. (Reform of the Currency in Austria-Hungary 1892, p. 336)

^ ab Contemporary designations of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class refer the ships as "torpedo ram cruisers" (German:Rammkreuzer). Most sources recognize the ships as protected cruisers.(Sondhaus 1994, pp. 99-100) (Greger 1976, p. 27) (Greger 1976, p. 29)

^ ab Greger writes that the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class had an overall length of 103.9 meters (340 ft 11 in), while Gardiner gives a figure of 103.7 meters (340 ft 3 in). (Greger 1976, p. 29) (Gardiner 1979, p. 278)

^ ab Greger describes the beam of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class as measuring 14.75 meters (48 ft 5 in). Gardiner states the beam for the ships was 14.8 meters (48 ft 7 in). (Greger 1976, p. 27) (Gardiner 1979, p. 278)

^ ab Greger lists the propulsion of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class was 8,000 shaft horsepower (6,000 kW). Gardiner gives a figure of 8,000–8,450 shaft horsepower (5,970–6,300 kW). (Greger 1976, p. 27) (Gardiner 1979, p. 278)

^ ab Greger claims that Kaiser Franz Joseph I had 444 officers and men, while Kaiserin Elisabeth had 427. Gardiner states the complement of both ships was 367 officers and men. (Greger 1976, p. 29) (Gardiner 1979, p. 278)

^ abc Greger states that the Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class had 40 cm (16 in) torpedo tubes, while Gardiner writes that the torpedo tubes on both ships measured 45 cm (18 in). (Greger 1976, p. 29) (Gardiner 1979, p. 278)

^ ab For political and traditional purposes, the Marinekommandant designated all of his proposed ships to the Austrian and Hungarian parliaments with the prefix "Ersatz" ("replacement"). Once a ship was launched, it would be formally named. The Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class cruisers were thus designated as replacement ships for the ironclads Lissa and Kaiser. While funding for the third ship was approved under the 1890 budget, authorization to construct it was never given and the vessel was never laid down. The ship was simply referred to as "Rammkreuzer C".

^ Greger states Kaiserin Elisabeth was scuttled on 3 November 1914, while Sondhaus writes it was 2 November. (Sondhaus 1994, p. 263) (Greger 1976, p. 29)

Citations

^ ab Greger 1976, p. 27.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 79.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 94.

^ Sokol 1968, p. 61.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 95–97.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 98–99.

^ abcd Sondhaus 1994, p. 100.

^ Pawlik 2003, p. 43.

^ Sieche 1995, p. 29.

^ ab Noppen 2016, p. 6.

^ ab Noppen 2016, p. 5.

^ abcde Sieche 1995, p. 28.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 128, 173.

^ ab Sondhaus 1994, p. 99.

^ Hiscox 1893, p. 14235.

^ abc Greger 1976, pp. 27, 29.

^ abcd Gardiner 1979, p. 278.

^ abc Hiscox 1893, p. 14236.

^ Dickson, O'Hara & Worth 2013, p. 25.

^ Sieche 1995, pp. 28–29.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 198–199.

^ Sieche 1995, p. 31.

^ Dickson, O'Hara & Worth 2013, p. 16.

^ abcdefg Sieche 1995, p. 32.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 101–102.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 110.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 124–125.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 125.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 131.

^ Sieche 1995, pp. 33–32.

^ abc Sieche 1995, pp. 34–35.

^ abc Sieche 1995, p. 35.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 185.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 185–186.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 232–234.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 245–246.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 246.

^ Koburger 2001, pp. 33, 35.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 251.

^ ab Sondhaus 1994, pp. 257–258.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 262.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 260.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 262–263.

^ Donko 2013, pp. 4, 156–162, 427.

^ ab Sondhaus 1994, p. 263.

^ Greger 1976, p. 29.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 365.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 285–286.

^ Koburger 2001, p. 59.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 318.

^ ab Sieche 1995, p. 34.

^ Halpern 2004, pp. 48–50.

^ Koburger 2001, p. 96.

^ Halpern 2004, p. 50.

^ Halpern 2004, pp. 52–53.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 322.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 144.

^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 326.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 350–351.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 351–352.

^ ab Sondhaus 1994, p. 352.

^ ab Sokol 1968, pp. 136–137, 139.

^ Koburger 2001, p. 118.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 353–354.

^ Halpern 1994, p. 177.

^ Gardiner & Gray 1984, p. 329.

^ Sondhaus 1994, pp. 357–359.

References

Dickson, W. David; O'Hara, Vincent; Worth, Richard (2013). To Crown the Waves: The Great Navies of the First World War. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1612510828..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Donko, Wilhelm M. (2013). Österreichs Kriegsmarine in Fernost: Alle Fahrten von Schiffen der k.(u.)k. Kriegsmarine nach Ostasien, Australien und Ozeanien von 1820 bis 1914 (in German). Berlin: epubli. ISBN 978-3844249125.

Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1984). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

Greger, René (1976). Austro-Hungarian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0623-2.

Halpern, Paul G. (1994). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

Halpern, Paul (2004). "The Cattaro Mutiny, 1918". In Bell, Christopher M.; Elleman, Bruce A. Naval Mutinies of the Twentieth Century: An International Perspective. London: Frank Cass. pp. 45–65. ISBN 978-0-7146-5460-7.

Hiscox, G. D. (January–June 1893). "The Austrian Ram-Cruiser Kaiserin Elisabeth". Scientific American Supplement. 35 (888): 14235–14236.CS1 maint: Date format (link)

Koburger, Charles (2001). The Central Powers in the Adriatic, 1914–1918: War in a Narrow Sea. Westport: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-313-00272-4.

Noppen, Ryan K. (2016). Austro-Hungarian Cruisers and Destroyers 1914–18. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781472814715.

Pawlik, Georg (2003). Des Kaisers Schwimmende Festungen: die Kasemattschiffe Österreich-Ungarns [The Kaiser's Floating Fortresses: The Casemate Ships of Austria-Hungary]. Vienna: Neuer Wissenschaftlicher Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7083-0045-0.

"Reform of the Currency in Austria-Hungary". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 55 (2): 333–339. 1892. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

Sieche, Erwin (1995). "The Kaiser Franz Joseph I. Class Torpedo-rams". In Roberts, John. Warship 1995. London: Conway Maratime Press. p. 27–39. ISBN 978-0-85177-654-5.

Sokol, Anthony (1968). The Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Navy. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 462208412.

Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867-1918: Navalism, Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9.

Further reading

Halpern, Paul G. (1987). The Naval War in the Mediterranean, 1914-1918. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0870214486.

Sieche, Erwin (2002). Kreuzer und Kreuzerprojekte der k.u.k. Kriegsmarine 1889–1918 [Cruisers and Cruiser Projects of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, 1889–1918] (in German). Hamburg. ISBN 978-3-8132-0766-8.

Vego, Milan N. (1996). Austro-Hungarian Naval Policy: 1904–14. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0714642093.