Looting

The plundering of the Frankfurter Judengasse, 22 August 1614

Looting, also referred to as sacking, ransacking, plundering, despoiling, despoliation, and pillaging, is the indiscriminate taking of goods by force as part of a military or political victory, or during a catastrophe, such as war,[1]natural disaster (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective),[2] or rioting.[3] The term is also used in a broader sense to describe egregious instances of theft and embezzlement, such as the "plundering" of private or public assets by governments.[4]

The proceeds of all these activities can be described as booty, loot, plunder, spoils, or pillage.[5][6]

Looters attempting to enter a cycle shop in North London during the 2011 England riots

In armed conflict, pillage is prohibited by international law, and constitutes a war crime.[7]

Contents

1 Looting by type

1.1 In armed conflict

1.1.1 Prohibited under international law

1.2 Archaeological removals

1.3 Looting of industry

2 Measures against looting following disasters

3 Examples

3.1 By conquerors

3.2 By others

4 See also

5 References

6 Sources

Looting by type

In armed conflict

The sacking and looting of Mechelen by the Spanish troops led by the Duke of Alba, 2 October 1572

Looting by a victorious army during war has been common practice throughout recorded history. For foot soldiers, it was viewed as a way to supplement their often meagre income[8] and was part of the celebration of victory. On higher levels, the proud exhibition of loot was an integral part of the typical Roman triumph, and Genghis Khan was not unusual in proclaiming that the greatest happiness was "to vanquish your enemies ... to rob them of their wealth".[9]

In warfare in ancient times, the spoils of war included the defeated populations, which were often enslaved. The women and children were often absorbed into the victorious country's population.[10][11] In other pre-modern societies, objects made of precious metals were the preferred target of war looting, largely because of their easy portability. In many cases looting was an opportunity to obtain treasures that otherwise would not have been obtainable. Since the 18th century, works of art have increasingly become a popular target. In the 1930s and even more so during World War II, Nazi Germany engaged in large scale and organized looting of art and property.[12][13]

Looting, combined with poor military discipline, has occasionally been an army's downfall.[citation needed] In other cases, for example the Wahhabi sack of Karbala, loot has financed further victories.[14] Not all looters in wartime are conquerors; the looting of Vistula Land by its retreating defenders in 1915[15] was among the factors sapping the loyalty of Poland in World War I. Local civilians can also take advantage of a breakdown of order to loot public and private property, such as took place at the National Museum of Iraq in the course of the Iraq War in 2003.[16]Tolstoy's novel War and Peace describes widespread looting by Moscow's citizens before Napoleon's troops enter the city, and by French troops elsewhere.

Prohibited under international law

In armed conflict, pillage is prohibited by both customary international law and by treaty.[7] The prohibition against pillage was recognized in the Lieber Code, Brussels Declaration (1874), and Oxford Manual.[7] The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 (modified in 1954) obliges military forces not only to avoid destruction of enemy property, but to provide protection to it.[17] Article 8 of the Statute of the International Criminal Court provides that in international warfare, the "pillaging a town or place, even when taken by assault," is a war crime.[7] In the aftermath of World War II, a number of war criminals were prosecuted for pillage. Several people have been prosecuted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia for pillage.[7]

The Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 explicitly prohibits the looting of civilian property during wartime.[7][18]

Theoretically, to prevent such looting, unclaimed property is moved to the custody of the Custodian of Enemy Property, to be handled until being returned to its owner.

Archaeological removals

The term "looting" is also sometimes used to refer to antiquities being removed from countries by unauthorized people, either domestic people breaking the law seeking monetary gain, or by foreign nations, which are usually more interested in prestige or previously, "scientific discovery". An example of this might be the removal of the contents of Egyptian tombs which were transported to museums in Europe.[19] Other examples include the obelisks of Pharaoh Amenhotep II, in the (Oriental Museum, University of Durham, United Kingdom), Pharaoh Ptolemy IX, (Philae Obelisk, in Wimborne, Dorset, United Kingdom). Whether this constitutes "looting" is a debated point, with other parties pointing out that the Europeans were usually given permission of some sort, and that many of the treasures wouldn't have been discovered at all if the Europeans hadn't funded and organized the expeditions or digs that located them. Many of these antiquities have already been returned to their country of origin voluntarily.

Looting of industry

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Soviet forces systematically plundered the Soviet occupation zone of Germany, including the Recovered Territories which were to be transferred to Poland. They sent valuable industrial equipment, infrastructure and whole factories to the Soviet Union.[20][21]

Measures against looting following disasters

FAFN soldier caught by French Foreign Legion troops.

During a disaster, police and military are sometimes unable to prevent looting when they are overwhelmed by humanitarian or combat concerns, or cannot be summoned due to damaged communications infrastructure. Especially during natural disasters, some people find themselves forced to take what is not theirs in order to survive. How to respond to this, and where the line between unnecessary "looting" and necessary "scavenging" lies, is often a dilemma for governments.[22] In other cases, looting may be tolerated or even encouraged by governments for political or other reasons.

Examples

By conquerors

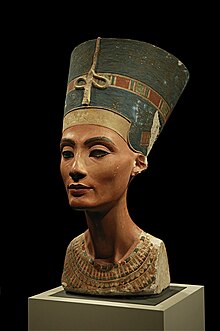

The iconic bust of Nefertiti, claimed by some to be illegally obtained by the Germans during excavations at Tell el-Amarna in 1912.[23][24]

Iraqi looters in the archaeological site of Isin

- Around the same time of the Hyksos invasion and occupation of Egypt (1650 BC – 1550 BC), Hebrew tradition has it that both Abraham and Moses were given property of Egypt by God. "In Genesis 15:14, the despoliation is an act of justifiable vengeance upon the oppressors of Israel. Yet in Exodus, God uses the plagues as an act of mercy to bring a knowledge of himself to Israel, Pharaoh, the Egyptians, and to the ends of the earth."[25] See Hyksos Iconoclasm and Genesis 13:2 and Genesis 15:14 and Exodus 12:36.

- Following the death of Valentinian III in 455, the Vandals invaded and extensively looted the city of Rome.

- In 870 AD, the Byzantine city of Melite (now Mdina, Malta) was captured by the Aghlabids under Sawāda Ibn Muḥammad. The city was destroyed, its churches looted and its population massacred. Marble from the city's churches was used to build the castle of Sousse.[26]

Mahmud of Ghazni repeatedly plundered the temple cities of Somnath, Mathura, Kannauj etc. of India between 1000 A.D and 1027 A.D.- After the siege of Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, the crusaders looted the city and transferred its riches to Italy.

- Roman Catholic troops of Imperial Field Marshal Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly committed the Sack of Magdeburg in 1631. Magdeburg's civilian population was quickly reduced from 30,000 to 5,000, giving rise to a new term in German for annihilation by atrocities: "Magdeburgization".

- In 1664 the Maratha leader Shivaji sacked and looted Surat.

- Between 1804 and 1814 Napoleon Bonaparte engaged in massive looting throughout Europe and Africa.

- In 1812, British and Portuguese soldiers sacked the Spanish city of Badajoz after they had captured it by siege. It was three days before the men were brought back into order.

- In 1860, European allied forces burned and looted the Yuan Ming Yuan in Beijing, and in 1900, the European Eight-Nation Alliance looted Beijing when they invaded China to put down the Boxer Uprising.[27] The extent to which Europeans looted is challenged by more recent evidence from Noel du Boulay, commanding officer in charge of security at the Summer Palace during the Boxer rebellion, who records that the Russians had already looted the Palace before the Europeans assumed responsibility. On 7 October 1900 he officially reports the condition of the Palace as he first encountered it. One of Du Boulay's main duties was to prevent further looting. An extensive catalogue of items in the palace was formally agreed with Shih Hsu, President of the Board of Ceremonies and Comptroller of the Imperial household when the Palace was handed back on 14 September 1901.[28]

- During World War II, Nazi Germany engaged in looting, particularly by Nazi military units known as the Kunstschutz ("Art Protection"). The Soviet Army also operated official trophy brigades to loot Germany and the Eastern European countries occupied by Germany (such as Poland). In Asia, the Empire of Japan, through the Imperial Japanese Army, also engaged in massive and systematic looting of valuables. The exact amount of looting during World War II will never be known, but it is estimated to be worth hundreds of billions of dollars. See:

- Baldin Collection

- Nazi plunder

- Yamashita's gold

By others

- In 1863, anti-draft riots in New York City during the American Civil War resulted in four days of arson, looting and violence against the city's free black population.[29]

- In 1939 through 1941, during the bombing of British cities by the German Luftwaffe several incidents of bomb-damaged buildings being looted by gangs of children, firemen, and the general public were reported.[30]

- In 1977, the New York Blackout resulted in massive rioting and looting throughout the city of New York.

- In 1989 during the US invasion of Panama, there was massive systematic looting in Panama City.[citation needed]

- In 1992, during the Rodney King riots, widespread looting occurred in Los Angeles, California.

- After the United States occupied Iraq in 2003, the absence of Iraqi police and the reluctance of the U.S. to act as a police force enabled looters to raid homes and businesses, especially in Baghdad, most notably the Iraqi National Museum. During the looting, many hospitals were stripped of nearly all supplies. However, upon investigation many of the looting claims were in fact exaggerated, most notably the Iraqi National Museum in which many curators had stored important artifacts in the vaults of Iraq's central bank.[31]

- In 2010 after the Haiti earthquake, slow distribution of the relief aid and the large number of affected people created concerns of civil unrest, marked by looting and mob justice against suspected looters.[32][33]

- During the 2011 London riots, gangs of youths undertook looting in a number of areas across the capital.[34] It has been suggested that rioting may have been organised,[35] but it is unclear by whom, and to what end. London had previously been subjected to looting following the Brixton riot of 1981, and by gangs of youths who took advantage of war damage during the Second World War.[36] The 2011 London looting was copied on subsequent nights in other cities around England, including Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham.[37]

- During 2015 in Baltimore, Maryland, after the funeral of Freddie Gray, looting and rioting took place in the Mondawmin neighborhood where the funeral had taken place.[38]

See also

- Conflict minerals

- Depredation

- Looted art

- Prize of war

References

^ "Baghdad protests over looting". BBC News. BBC. 2003-04-12. Retrieved 2010-10-22..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "World: Americas Looting frenzy in quake city". BBC News. 1999-01-28. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

^ "Argentine president resigns". BBC News. 2001-12-21. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

^ "Definition of the word loot". Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com, LLC. 2010.

^ "the definition of looting". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

^ "Booty - Define Booty at Dictionary.com".

^ abcdef Rule 52. Pillage is prohibited., Customary IHL Database, International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)/Cambridge University Press.

^ Hsi-sheng Chi, Warlord politics in China, 1916–1928, Stanford University Press, 1976,

ISBN 0-8047-0894-0, str. 93

^ Henry Hoyle Howorth History of the Mongols from the 9th to the 19th Century: Part 1 the Mongols Proper and the Kalmyks, Cosimo Inc. 2008.

^ John K. Thorton, African Background in American Colonization, in The Cambridge economic history of the United States, Stanley L. Engerman, Robert E. Gallman (ed.), Cambridge University Press, 1996,

ISBN 0-521-39442-2, p. 87. "African states waged war to acquire slaves [...] raids that appear to have been more concerned with obtaining loot (including slaves) than other objectives."

^ Sir John Bagot Glubb, The Empire of the Arabs, Hodder and Stoughton, 1963, p.283. "...thousand Christian captives formed part of the loot and were subsequently sold as slaves in the markets of Syria".

^ (in Polish) J. R. Kudelski, Tajemnice nazistowskiej grabieży polskich zbiorów sztuki, Warszawa 2004.

^ "Nazi loot claim 'compelling'". BBC News. October 2, 2002. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

^ Wayne H. Bowen, The History of Saudi Arabia, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008, p. 73.

ISBN 0-313-34012-9

^ (in Polish) Andrzej Garlicki, Z dziejów Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej, Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 1986,

ISBN 83-02-02245-4, p. 147

^ STEVEN LEE MYERS, Iraq Museum Reopens Six Years After Looting, New York Times, February 23, 2009

^ Barbara T. Hoffman, Art and Cultural Heritage: Law, Policy, and Practice, Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 57.

ISBN 0-521-85764-3

^ E. Lauterpacht, C. J. Greenwood, Marc Weller, The Kuwait Crisis: Basic Documents, Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 154.

ISBN 0-521-46308-4

^ "Egypt's Antiquities Chief Combines Passion, Clout to Protect Artifacts". National Geographic News. October 24, 2006.

^ "MIĘDZY MODERNIZACJĄ A MARNOTRAWSTWEM" (in Polish). Institute of National Remembrance. Archived from the original on 2005-03-21. See also other copy online Archived 2007-04-26 at the Wayback Machine.

^ "ARMIA CZERWONA NA DOLNYM ŚLĄSKU" (in Polish). Institute of National Remembrance. Archived from the original on 2005-03-21.

^ "Indonesian food minister tolerates looting". BBC News. July 21, 1998. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

^ (in English) "Top 10 Plundered Artifacts – Nefertiti's Bust". www.time.com. March 5, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-27. "German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt ... claimed to have an agreement with the Egyptian government that included rights to half his finds ... But a new document suggests Borchardt intentionally misled the Egyptian government about Nefertiti."

^ Will Nefertiti Return to Egypt for a Brief Visit? Egypt Asks Germany for a Majestic Loan by Stan Parchin (June 17, 2006) about.com

^ Joel Stevens Allen, The Despoliation of Egypt: In Pre-Rabbinic, Rabbinic and Patristic Traditions, pg. 128, 2008, Brill Academic Pub,

ISBN 90-04-16745-5.

^ Brincat, Joseph M. "New Light on the Darkest Age in Malta's History" (PDF). melitensiawth.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2015.

^ Hevia, James Louis (2003). English Lessons: The Pedagogy of Imperialism in Nineteenth-Century China. Durham; Hong Kong: Duke University Press; Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3151-9..

^ Du Boulay, F.R.H. (2011). Servants of Empire: An Imperial Memoir of a British Family. London; New York: I.B Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-571-7..

^ "On This Day: August 1, 1863". The New York Times.

^ "A nation of looters: it even happened in the Blitz". The Week UK.

^ "Penn Museum – University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology". upenn.edu.

^ "Mob justice in Haiti". thestar.com. Toronto. 17 January 2010.

^ Romero, Simon; Lacey, Marc (17 January 2010). "Looting Flares Where Authority Breaks Down" – via NYTimes.com.

^ "Further riots in London as violence spreads across England". BBC News. August 9, 2011.

^ Lewis, Paul; Taylor, Matthew; Quinn, Ben (August 8, 2011). "Second night of violence in London – and this time it was organised". The Guardian. London.

^ MacKay, Robert (2002). Half the Battle: Civilian Morale in Britain During the Second World War. Manchester University Press. p. 84.

ISBN 0-7190-5894-5.

^ "UK riots: Trouble erupts in English cities". BBC News. August 10, 2011.

^ "Baltimore Enlists National Guard and a Curfew to Fight Riots and Looting". The New York Times. April 27, 2015.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Looting. |

- Stewart, James, "Corporate War Crimes: Prosecuting Pillage of Natural Resources", 2010

- Abudu, Margaret, et al., "Black Ghetto Violence: A Case Study Inquiry into the Spatial Pattern of Four Los Angeles Riot Event-Types," 44 Social Problems 483 (1997)

- Curvin, Robert and Bruce Porter, Blackout Looting (1979)

- Dynes, Russell & Enrico L. Quarantelli, "What Looting in Civil Disturbances Really Means," in Modern Criminals 177 (James F. Short, Jr. ed. 1970)

- Green, Stuart P., "Looting, Law, and Lawlessness," 81 Tulane Law Review 1129 (2007)

- Mac Ginty, "Looting in the Context of Violent Conflict: A Conceptualisation and Typology," 25 Third World Quarterly 857 (2004)