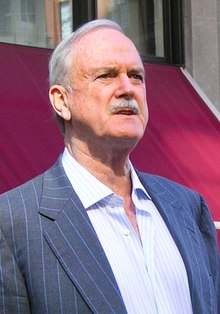

John Cleese

John Cleese | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | John Marwood Cleese (1939-10-27) 27 October 1939 Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, England |

| Alma mater | Downing College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Actor, voice actor, comedian, screenwriter, producer |

| Years active | 1961–present |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 2 |

| Website | johncleese.com |

John Marwood Cleese (/kliːz/; born 27 October 1939) is an English actor, voice actor, comedian, screenwriter, and producer. He achieved success at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and as a scriptwriter and performer on The Frost Report. In the late 1960s, he co-founded Monty Python, the comedy troupe responsible for the sketch show Monty Python's Flying Circus and the four Monty Python films: And Now for Something Completely Different, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Life of Brian and The Meaning of Life.

In the mid-1970s, Cleese and his first wife, Connie Booth, co-wrote and starred in the British sitcom Fawlty Towers, with Cleese receiving the 1980 BAFTA for Best Entertainment Performance. Later, he co-starred with Kevin Kline, Jamie Lee Curtis, and former Python colleague Michael Palin in A Fish Called Wanda and Fierce Creatures, both of which he also wrote. He also starred in Clockwise and has appeared in many other films, including two James Bond films as R and Q, two Harry Potter films, and the last three Shrek films.

With Yes Minister writer Antony Jay, he co-founded Video Arts, a production company making entertaining training films. In 1976, Cleese co-founded The Secret Policeman's Ball benefit shows to raise funds for the human rights organisation Amnesty International.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Career

2.1 Pre-Python

2.2 Monty Python

2.2.1 Partnership with Graham Chapman

2.3 Post-Python activities

2.3.1 Fawlty Towers

2.4 1980s and 1990s

2.5 2000s and 2010s

2.6 Admiration for black humour

3 Politics

4 Anti-smoking campaign

5 Personal life

6 Filmography

6.1 Film

6.2 Television

6.3 Video games

6.4 Radio credits

6.5 Stage

6.6 Television advertisements

7 Honours and tributes

7.1 Scholastic

8 Bibliography

8.1 Dialogues

9 See also

10 Notes

11 References

12 Published works

13 External links

Early life

Cleese was born in Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, the only child of Reginald Francis Cleese (1893–1972), an insurance salesman (whose father was an insurance clerk), and his wife Muriel Evelyn (née Cross; 1899–2000 the daughter of an auctioneer).[1] His family's surname was originally Cheese, but his father had thought it was embarrassing and changed it when he enlisted in the Army during the First World War.[2] As a child, Cleese supported Bristol City FC and Somerset County Cricket Club.[3][4] Cleese was educated at St Peter's Preparatory School (paid for by money his mother inherited[5]), where he received a prize for English and did well at cricket and boxing. When he was 13, he was awarded an exhibition at Clifton College, an English public school in Bristol. He was already more than 6 feet (1.83 m) tall by then.

Cleese allegedly defaced the school grounds, as a prank, by painting footprints to suggest that the statue of Field Marshal Earl Haig had got down from his plinth and gone to the toilet.[6] Cleese played cricket in the First XI and did well academically, passing 8 O-Levels and 3 A-Levels in mathematics, physics, and chemistry.[7][8] In his autobiography So, Anyway, he says that discovering, aged 17, he had not been made a house prefect by his housemaster affected his outlook: "It was not fair and therefore it was unworthy of my respect ... I believe that this moment changed my perspective on the world."

He could not go straight to Cambridge, as the ending of National Service meant there were twice the usual number of applicants for places, so he returned to his prep school for two years[9] to teach science, English, geography, history, and Latin[10] (he drew on his Latin teaching experience later for a scene in Life of Brian, in which he corrects Brian's badly written Latin graffiti).[11] He then took up a place he had won at Downing College, Cambridge, to read Law. He also joined the Cambridge Footlights. He recalled that he went to the Cambridge Guildhall, where each university society had a stall, and went up to the Footlights stall where he was asked if he could sing or dance. He replied "no" as he was not allowed to sing at his school because he was so bad, and if there was anything worse than his singing, it was his dancing. He was then asked "Well, what do you do?" to which he replied, "I make people laugh."[9]

At the Footlights theatrical club, he spent a lot of time with Tim Brooke-Taylor and Bill Oddie and met his future writing partner Graham Chapman.[9] Cleese wrote extra material for the 1961 Footlights Revue I Thought I Saw It Move,[9][12] and was Registrar for the Footlights Club during 1962. He was also in the cast of the 1962 Footlights Revue Double Take![9][12] Cleese graduated from Cambridge in 1963 with a 2:1. Despite his successes on The Frost Report, his father would send him cuttings from The Daily Telegraph offering management jobs in places like Marks and Spencer.[13]

Career

Pre-Python

Cleese was a scriptwriter, as well as a cast member, for the 1963 Footlights Revue A Clump of Plinths.[9][12] The revue was so successful at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe that it was renamed Cambridge Circus and taken to the West End in London and then on a tour of New Zealand and Broadway, with the cast also appearing in some of the revue's sketches on The Ed Sullivan Show in October 1964.[9]

After Cambridge Circus, Cleese briefly stayed in America, performing on and off-Broadway. While performing in the musical Half a Sixpence,[9] Cleese met future Python Terry Gilliam, as well as American actress Connie Booth, whom he married on 20 February 1968.[9] At their wedding at a Unitarian Church in Manhattan, the couple attempted to ensure an absence of any theistic language. "The only moment of disappointment," Cleese recalled, "came at the very end of the service when I discovered that I'd failed to excise one particular mention of the word 'God.'"[14] Later Booth would become a writing partner.

He was soon offered work as a writer with BBC Radio, where he worked on several programmes, most notably as a sketch writer for The Dick Emery Show. The success of the Footlights Revue led to the recording of a short series of half-hour radio programmes, called I'm Sorry, I'll Read That Again, which were so popular that the BBC commissioned a regular series with the same title that ran from 1965 to 1974. Cleese returned to Britain and joined the cast.[9] In many episodes, he is credited as "John Otto Cleese" (according to Jem Roberts, this may have been due to the embarrassment of his actual middle name Marwood).[15]

Also in 1965, Cleese and Chapman began writing on The Frost Report. The writing staff chosen for The Frost Report consisted of a number of writers and performers who would go on to make names for themselves in comedy. They included co-performers from I'm Sorry, I'll Read That Again and future Goodies Bill Oddie and Tim Brooke-Taylor, and also Frank Muir, Barry Cryer, Marty Feldman, Ronnie Barker, Ronnie Corbett, Dick Vosburgh and future Python members Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin. While working on The Frost Report, the future Pythons developed the writing styles that would make their collaboration significant. Cleese's and Chapman's sketches often involved authority figures, some of whom were performed by Cleese, while Jones and Palin were both infatuated with filmed scenes that opened with idyllic countryside panoramas. Idle was one of those charged with writing David Frost's monologue. During this period Cleese met and befriended influential British comedian Peter Cook.

It was as a performer on The Frost Report that Cleese achieved his breakthrough on British television as a comedy actor, appearing as the tall, patrician figure in the classic class sketch, contrasting comically in a line-up with the shorter, middle class Ronnie Barker and the even shorter, working class Ronnie Corbett. This series was so popular that in 1966 Cleese and Chapman were invited to work as writers and performers with Brooke-Taylor and Feldman on At Last the 1948 Show,[9] during which time the Four Yorkshiremen sketch was written by all four writers/performers (the Four Yorkshiremen sketch is now better known as a Monty Python sketch).[16] Cleese and Chapman also wrote episodes for the first series of Doctor in the House (and later Cleese wrote six episodes of Doctor at Large on his own in 1971). These series were successful, and in 1969 Cleese and Chapman were offered their very own series. However, owing to Chapman's alcoholism, Cleese found himself bearing an increasing workload in the partnership and was, therefore, unenthusiastic about doing a series with just the two of them. He had found working with Palin on The Frost Report an enjoyable experience and invited him to join the series. Palin had previously been working on Do Not Adjust Your Set with Idle and Jones, with Terry Gilliam creating the animations. The four of them had, on the back of the success of Do Not Adjust Your Set, been offered a series for Thames Television, which they were waiting to begin when Cleese's offer arrived. Palin agreed to work with Cleese and Chapman in the meantime, bringing with him Gilliam, Jones, and Idle.

Monty Python

Monty Python's Flying Circus ran for four seasons from October 1969 to December 1974 on BBC Television, though Cleese quit the show after the third. Cleese's two primary characterisations were as a sophisticated and a stressed-out loony. He portrayed the former as a series of announcers, TV show hosts, and government officials (for example, "The Ministry of Silly Walks"). The latter is perhaps best represented in the "Cheese Shop" and by Cleese's Mr Praline character, the man with a dead Norwegian Blue parrot and a menagerie of other animals all named "Eric". He was also known for his working class "Sergeant Major" character, who worked as a Police Sergeant, Roman Centurion, etc. He is also seen as the opening announcer with the now famous line "And now for something completely different", although in its premiere in the sketch "Man with Three Buttocks", the phrase was spoken by Eric Idle.

Partnership with Graham Chapman

Along with Gilliam's animations, Cleese's work with Graham Chapman provided Python with its darkest and angriest moments, and many of his characters display the seething suppressed rage that later characterised his portrayal of Basil Fawlty.

Unlike Palin and Jones, Cleese and Chapman wrote together in the same room; Cleese claims that their writing partnership involved Cleese doing most of the work, while Chapman sat back, not speaking for long periods before suddenly coming out with an idea that often elevated the sketch to a new level. A classic example of this is the "Dead Parrot sketch", envisaged by Cleese as a satire on poor customer service, which was originally to have involved a broken toaster and later a broken car (this version was actually performed and broadcast on the pre-Python special How to Irritate People). It was Chapman's suggestion to change the faulty item into a dead parrot, and he also suggested that the parrot be specifically a "Norwegian Blue", giving the sketch a surreal air which made it far more memorable.

Their humour often involved ordinary people in ordinary situations behaving absurdly for no obvious reason. Like Chapman, Cleese's poker face, clipped middle class accent, and intimidating height allowed him to appear convincingly as a variety of authority figures, such as policemen, detectives, Nazi officers or government officials—which he would then proceed to undermine. Most famously, in the "Ministry of Silly Walks" sketch (actually written by Palin and Jones), Cleese exploits his stature as the crane-legged civil servant performing a grotesquely elaborate walk to his office.

Chapman and Cleese also specialised in sketches where two characters would conduct highly articulate arguments over completely arbitrary subjects, such as in the "cheese shop", the "dead parrot" sketch and "Argument Clinic", where Cleese plays a stone-faced bureaucrat employed to sit behind a desk and engage people in pointless, trivial bickering. All of these roles were opposite Palin (who Cleese often claims is his favourite Python to work with)—the comic contrast between the towering Cleese's crazed aggression and the shorter Palin's shuffling inoffensiveness is a common feature in the series. Occasionally, the typical Cleese–Palin dynamic is reversed, as in "Fish Licence", wherein Palin plays the bureaucrat with whom Cleese is trying to work.

Though the programme lasted four series, by the start of series 3, Cleese was growing tired of dealing with Chapman's alcoholism. He felt, too, that the show's scripts had declined in quality. For these reasons, he became restless and decided to move on. Though he stayed for the third series, he officially left the group before the fourth season. Despite this, he remained friendly with the group, and all six began writing Monty Python and the Holy Grail; Cleese received a credit on three episodes of the fourth series which used material from these sessions, though he was officially unconnected with the fourth series. Cleese returned to the troupe to co-write and co-star in the Monty Python films Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Monty Python's Life of Brian and Monty Python's The Meaning of Life, and participated in various live performances over the years.

Post-Python activities

From 1970 to 1973, Cleese served as rector of the University of St Andrews.[17] His election proved a milestone for the university, revolutionising and modernising the post. For instance, the rector was traditionally entitled to appoint an "Assessor", a deputy to sit in his place at important meetings in his absence. Cleese changed this into a position for a student, elected across campus by the student body, resulting in direct access and representation for the student body.[18]

Around this time, Cleese worked with comedian Les Dawson on his sketch/stand-up show Sez Les. The differences between the two physically (the tall, lean Cleese and the short, stout Dawson) and socially (the public school, and then Cambridge-educated Cleese and the working class, self-educated Mancunian Dawson) were marked, but both worked well together from series 8 onwards until the series ended in 1976.[19][20]

Fawlty Towers

Cleese achieved greater prominence in the United Kingdom as the neurotic hotel manager Basil Fawlty in Fawlty Towers, which he co-wrote with his wife Connie Booth. The series won three BAFTA awards when produced and in 2000, it topped the British Film Institute's list of the 100 Greatest British Television Programmes. The series also featured Prunella Scales as Basil's acerbic wife Sybil, Andrew Sachs as the much abused Spanish waiter Manuel ("... he's from Barcelona"), and Booth as waitress Polly, the series' voice of sanity. Cleese based Basil Fawlty on a real person, Donald Sinclair, whom he had encountered in 1970 while the Monty Python team were staying at the Gleneagles Hotel in Torquay while filming inserts for their television series. Reportedly, Cleese was inspired by Sinclair's mantra, "I could run this hotel just fine if it weren't for the guests." He later described Sinclair as "the most wonderfully rude man I have ever met," although Sinclair's widow has said her husband was totally misrepresented in the series. During the Pythons' stay, Sinclair allegedly threw Idle's briefcase out of the hotel "in case it contained a bomb," complained about Gilliam's "American" table manners, and threw a bus timetable at another guest after they dared to ask the time of the next bus to town.

The first series was screened from 19 September 1975 on BBC 2, initially to poor reviews,[21] but gained momentum when repeated on BBC 1 the following year. Despite this, a second series did not air until 1979, by which time Cleese's marriage to Booth had ended, but they revived their collaboration for the second series. Fawlty Towers consisted of only twelve episodes; Cleese and Booth both maintain that this was to avoid compromising the quality of the series.

In December 1977, Cleese appeared as a guest star on The Muppet Show.[22] Cleese was a fan of the show and co-wrote much of the episode.[23]

Cleese also made a cameo appearance in their 1981 film The Great Muppet Caper.

Cleese won the TV Times award for Funniest Man on TV – 1978–79.[24]

1980s and 1990s

During the 1980s and 1990s, Cleese focused on film, though he did work with Peter Cook in his one-off TV special Peter Cook and Co. in 1980. In the same year, Cleese played Petruchio, in Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew in the BBC Television Shakespeare series. In 1981 he starred with Sean Connery and Michael Palin in the Terry Gilliam-directed Time Bandits as Robin Hood. He also participated in Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl (1982) and starred in The Secret Policeman's Ball for Amnesty International. In 1985, Cleese had a small dramatic role as a sheriff in Silverado, which had an all-star cast that included Kevin Kline, with whom he would star in A Fish Called Wanda three years later. In 1986, he starred in Clockwise as an uptight school headmaster obsessed with punctuality and constantly getting into trouble during a journey to speak at the Headmasters' Conference.

Cleese at the 1989 Academy Awards

Timed with the 1987 UK elections, he appeared in a video promoting proportional representation.[25]

In 1988, he wrote and starred in A Fish Called Wanda as the lead, Archie Leach, along with Jamie Lee Curtis, Kevin Kline, and Michael Palin. Wanda was a commercial and critical success, and Cleese was nominated for an Academy Award for his script. Cynthia Cleese starred as Leach's daughter.

Graham Chapman was diagnosed with throat cancer in 1989; Cleese, Michael Palin, Peter Cook, and Chapman's partner David Sherlock, witnessed Chapman's death. Chapman's death occurred a day before the 20th anniversary of the first broadcast of Flying Circus, with Jones commenting, "the worst case of party-pooping in all history". Cleese's eulogy at Chapman's memorial service—in which he "became the first person ever at a British memorial service to say 'fuck'"[attribution needed]—has since become legendary.[26]

Cleese would later play a supporting role in Kenneth Branagh's adaptation of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein alongside Branagh himself and Robert De Niro. He also produced and acted in a number of successful business training films, including Meetings, Bloody Meetings, and More Bloody Meetings. These were produced by his company Video Arts.

With Robin Skynner, the group analyst and family therapist, Cleese wrote two books on relationships: Families and How to Survive Them, and Life and How to Survive It. The books are presented as a dialogue between Skynner and Cleese.

In 1996, Cleese declined the British honour of Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE). The follow-up to A Fish Called Wanda, Fierce Creatures—which again starred Cleese alongside Kevin Kline, Jamie Lee Curtis, and Michael Palin—was also released that year, but was greeted with mixed reception by critics and audiences. Cleese has since often stated that making the second film had been a mistake. When asked by his friend, director and restaurant critic Michael Winner, what he would do differently if he could live his life again, Cleese responded, "I wouldn't have married Alyce Faye Eichelberger and I wouldn't have made Fierce Creatures."[27]

In 1999, Cleese appeared in the James Bond film, The World Is Not Enough as Q's assistant, referred to by Bond as "R". In 2002, when Cleese reprised his role in Die Another Day, the character was promoted, making Cleese the new quartermaster (Q) of MI6. In 2004, Cleese was featured as Q in the video game James Bond 007: Everything or Nothing, featuring his likeness and voice. Cleese did not appear in the subsequent Bond films, Casino Royale, Quantum of Solace and Skyfall; in the latter film, Ben Whishaw was cast in the role of Q.

2000s and 2010s

Cleese is Provost's Visiting Professor at Cornell University, after having been Andrew D. White Professor-at-Large from 1999 to 2006. He makes occasional well-received appearances on the Cornell campus.

In 2001, Cleese was cast in the comedy Rat Race as the eccentric hotel owner Donald P. Sinclair, the name of the Torquay hotel owner on whom he had based the character of Basil Fawlty. In 2002, Cleese made a cameo appearance in the film The Adventures of Pluto Nash in which he played "James", a computerised chauffeur of a hover car stolen by the title character (played by Eddie Murphy). The vehicle is subsequently destroyed in a chase, leaving the chauffeur stranded in a remote place on the moon. In 2003, Cleese appeared as Lyle Finster on the US sitcom Will & Grace. His character's daughter, Lorraine, was played by Minnie Driver. In the series, Lyle Finster briefly marries Karen Walker (Megan Mullally). In 2004, Cleese was credited as co-writer of a DC Comics graphic novel titled Superman: True Brit.[28] Part of DC's "Elseworlds" line of imaginary stories, True Brit, mostly written by Kim Howard Johnson, suggests what might have happened had Superman's rocket ship landed in Britain, not America.

From 10 November to 9 December 2005, Cleese toured New Zealand with his stage show, John Cleese—His Life, Times and Current Medical Problems. Cleese described it as "a one-man show with several people in it, which pushes the envelope of acceptable behaviour in new and disgusting ways". The show was developed in New York City with William Goldman and includes Cleese's daughter Camilla as a writer and actor (the shows were directed by Australian Bille Brown). His assistant of many years, Garry Scott-Irvine, also appeared and was listed as a co-producer. The show then played in universities in California and Arizona from 10 January to 25 March 2006 under the title "Seven Ways to Skin an Ocelot".[29] His voice can be downloaded for directional guidance purposes as a downloadable option on some personal GPS-navigation device models by company TomTom.

In a 2005 poll of comedians and comedy insiders, The Comedians' Comedian, Cleese was voted second only to Peter Cook. Also in 2005, a long-standing piece of Internet humour, "The Revocation of Independence of the United States", was wrongly attributed to Cleese. In 2006, Cleese hosted a television special of football's greatest kicks, goals, saves, bloopers, plays, and penalties, as well as football's influence on culture (including the famous Monty Python sketch "Philosophy Football"), featuring interviews with pop culture icons Dave Stewart, Dennis Hopper, and Henry Kissinger, as well as eminent footballers including Pelé, Mia Hamm, and Thierry Henry. The Art of Soccer with John Cleese[30] was released in North America on DVD in January 2009 by BFS Entertainment & Multimedia. Also in 2006, Cleese released the song "Don't Mention the World Cup".

Cleese lent his voice to the BioWare video game Jade Empire. His role was that of an "outlander" named Sir Roderick Ponce von Fontlebottom the Magnificent Bastard, stranded in the Imperial City of the Jade Empire. His character is essentially a British colonialist stereotype who refers to the people of the Jade Empire as "savages in need of enlightenment". His armour has the design of a fork stuck in a piece of cheese. He also had a cameo appearance in the computer game Starship Titanic as "The Bomb" (credited as "Kim Bread"), designed by Douglas Adams.

In 2007, Cleese appeared in ads for Titleist as a golf course designer named "Ian MacCallister", who represents "Golf Designers Against Distance". Also in 2007, he started filming the sequel to The Pink Panther, titled The Pink Panther 2, with Steve Martin and Aishwarya Rai. On 27 September 2007, Cleese announced he was to produce a series of video podcasts called HEADCAST. Cleese released the first episode of this series in April 2008 on his own website, headcast.co.uk.

Cleese collaborated with Los Angeles Guitar Quartet member William Kanengiser in 2008 on the text to the performance piece "The Ingenious Gentleman of La Mancha". Cleese, as narrator, and the LAGQ premiered the work in Santa Barbara. 2008 also saw reports of Cleese working on a musical version of A Fish Called Wanda with his daughter Camilla.

At the end of March 2009, Cleese published his first article as "Contributing Editor" to The Spectator: "The real reason I had to join The Spectator".[31] Cleese has also hosted comedy galas at the Montreal Just for Laughs comedy festival in 2006, and again in 2009. Towards the end of 2009 and into 2010, Cleese appeared in a series of television adverts for the Norwegian electric goods shop chain, Elkjøp.[32] In March 2010 it was announced that Cleese would be playing Jasper in the video game Fable III.[33]

In 2009 and 2010, Cleese toured Scandinavia and the US with his Alimony Tour Year One and Year Two. In May 2010, it was announced that this tour would extend to the UK (his first tour in the UK), set for May 2011. The show is dubbed the "Alimony Tour" in reference to the financial implications of Cleese's divorce. The UK tour started in Cambridge on 3 May, visiting Birmingham, Nottingham, Salford, York, Liverpool, Leeds, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Oxford, Bristol and Bath (the Alimony Tour DVD was recorded on 2 July, the final Bath date).[34] Later in 2011 John took his Alimony Tour to South Africa. He played Cape Town on the 21 & 22 October before moving over to Johannesburg where he played from 25 to 30 October. In January 2012 he took his one-man show to Australia, starting in Perth on 22 Jan and throughout the next 4 months visited Adelaide, Brisbane, Gold Coast, Newcastle, New South Wales, Melbourne, Sydney, and finished up during April in Canberra.

In October 2010, Cleese was featured in the launch of an advertising campaign by The Automobile Association for a new home emergency response product.[35] He appeared as a man who believed the AA could not help him during a series of disasters, including water pouring through his ceiling, with the line "The AA? For faulty showers?" During 2010, Cleese appeared in a series of radio advertisements for the Canadian insurance company Pacific Blue Cross, in which he plays a character called "Dr. Nigel Bilkington, Chief of Medicine for American General Hospital".[36][37]

In May 2012 he did a week run of shows in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates. Entitled 'An Evening with John Cleese' he was at the Madinat Theatre, Souk Madinat Jumeirah.

In 2012, Cleese was cast in Hunting Elephants, an upcoming heist comedy by Israeli filmmaker Reshef Levi. Cleese had to quit just prior to filming due to heart trouble and was replaced by Patrick Stewart.[38][39][40]

Between September and October 2013, Cleese embarked on his first ever cross-Canada comedy tour. Entitled "John Cleese: Last Time to See Me Before I Die tour", he visited Halifax, Ottawa, Toronto, Edmonton, Calgary, Victoria and finished in Vancouver, performing to mostly sold-out venues.[41] Cleese returned to the stage in Dubai in November 2013, where he performed to a sold-out theatre.[42]

Cleese was interviewed and appears as himself in filmmaker Gracie Otto's 2013 documentary film The Last Impresario, about Cleese's longtime friend and colleague Michael White. White produced Monty Python and the Holy Grail and Cleese's pre-Python comedy production Cambridge Circus.[43]

At a comic press conference in November 2013, Cleese and other surviving members of the Monty Python comedy group announced a reuniting performance to be held in July 2014.[44]

In a Reddit Ask Me Anything interview, Cleese expressed regret that he had turned down the role played by Robin Williams in The Birdcage, the butler in The Remains of the Day, and the clergyman played by Peter Cook in The Princess Bride.[45]

Admiration for black humour

In his Alimony Tour Cleese explained the origin of his fondness for black humour, the only thing that he inherited from his mother. Examples of it are the Dead Parrot sketch, "The Kipper and the Corpse" episode of Fawlty Towers, his clip for the 1992 BBC2 mockumentary "A Question of Taste", the Undertakers sketch, the Mr Creosote character in The Meaning of Life, and his eulogy at Graham Chapman's memorial service.

Cleese blamed his mother, who lived to the age of 101, for his problems in relationships with women, saying: "It cannot be a coincidence that I spent such a large part of my life in some form of therapy and that the vast majority of the problems I was dealing with involved relationships with women."[46]

Politics

A long-running supporter of the Liberal Democrats[47] having previously been a Labour party voter, Cleese switched to the SDP after their formation in 1981, and during the 1987 general election, Cleese recorded a nine-minute party political broadcast for the SDP–Liberal Alliance, which spoke about the similarities and failures of the other two parties in a more humorous tone than standard political broadcasts. Cleese has since appeared in broadcasts for the Liberal Democrats, in the 1997 general election and narrating a radio election broadcast for the party during the 2001 general election.[48]

In 2008, Cleese expressed support for Barack Obama and his presidential candidacy, offering his services as a speech writer.[49] He was an outspoken critic of Republican Vice-Presidential candidate Sarah Palin, saying that "Michael Palin is no longer the funniest Palin".[50] The same year, he wrote a satirical poem about Fox News commentator Sean Hannity for Countdown with Keith Olbermann.[51]

In 2011, Cleese declared his appreciation for Britain's coalition government between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, saying: "I think what's happening at the moment is rather interesting. The Coalition has made everything a little more courteous and a little more flexible. I think it was quite good that the Liberal Democrats had to compromise a bit with the Tories." He also criticised the previous Labour government, commenting: "Although my inclinations are slightly left-of-centre, I was terribly disappointed with the last Labour government. Gordon Brown lacked emotional intelligence and was never a leader." Cleese also declared his support for proportional representation.[52]

In April 2011, Cleese revealed that he had declined a life peerage for political services in 1999. Outgoing leader of the Liberal Democrats Paddy Ashdown had put forward the suggestion shortly before stepping down, with the idea that Cleese would take the party whip and sit as a working peer, but the actor quipped that he "realised this involved being in England in the winter and I thought that was too much of a price to pay."[53]

In an interview with The Daily Telegraph in 2014, Cleese expressed political interest with regard to the UK Independence Party, saying that although he was in doubt as to whether he was prepared to vote for it, he was attracted to its challenge to the established political order and the radicalism of its policies with regard to the United Kingdom's membership of the European Union. He expressed support for immigration, but also concern about the integration of immigrants into British culture.[54]

Talking to Der Spiegel in 2015, Cleese expressed a critical view on what he saw as a plutocracy that was unhealthily developing control of the governance of the First World's societies, stating that he had reached a point when he "saw that our existence here is absolutely hopeless. I see the rich have got a stranglehold on us. If somebody had said that to me when I was 20, I would have regarded him as a left-wing loony."[55]

In 2016, Cleese publicly supported Brexit and the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union in the referendum on the issue.[56] He tweeted: "If I thought there was any chance of major reform in the EU, I'd vote to stay in. But there isn't. Sad." However, two years later, Cleese announced that he was leaving the UK to relocate in the Caribbean island of Nevis partly over frustration over Brexit, including "dreadful lies" by the right concerning investment in public services.[57]

During then-Republican nominee Donald Trump's run for the US Presidency in 2016, Cleese described Trump as "a narcissist, with no attention span, who doesn't have clear ideas about anything and makes it all up as he goes along".[58] He had previously described the leadership of the Republican Party as "the most cynical, most disgracefully immoral people I've ever come across in a Western civilisation".[54]

Anti-smoking campaign

In 1992, the UK Health Education Authority (subsequently the Health Development Agency, now merged into the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) recruited Cleese—an ex-smoker—to star in a series of anti-smoking public service announcements (PSAs) on British television, which took the form of sketches rife with morbid humor about smoking and were designed to encourage adult smokers to quit.[59] In a controlled study of regions of central and northern England, one region received no intervention, the PSAs were broadcast in two regions, and one region received both the PSAs plus locally organised anti-tobacco campaigning.[59] The study found that smokers in regions where the PSAs were broadcast were about half again as likely to have quit at the 18-month follow-up point as those who did not see them, irrespective of the local anti-tobacco campaign.[59]

Personal life

Cleese met Connie Booth in the US and they married in 1968.[21] In 1971, Booth gave birth to Cynthia Cleese, their only child. With Booth, Cleese wrote the scripts for and co-starred in both series of Fawlty Towers, even though the two were actually divorced before the second series was finished and aired. Cleese and Booth are said to have remained close friends since. Cleese has two grandchildren, Evan and Olivia, through his eldest daughter's marriage to Ed Solomon.

Cleese married American actress Barbara Trentham in 1981.[60] Their daughter Camilla, Cleese's second child, was born in 1984. He and Trentham divorced in 1990. During this time, Cleese moved to Los Angeles.

In 1992, he married American psychotherapist Alyce Faye Eichelberger. They divorced in 2008. The divorce settlement left Eichelberger with £12 million in finance and assets, including £600,000 a year for seven years. Cleese said, "What I find so unfair is that if we both died today, her children would get much more than mine ... I got off lightly. Think what I'd have had to pay Alyce if she had contributed anything to the relationship – such as children, or a conversation."[61]

Less than a year later, he returned to the UK, where he has property in London and a home on the Royal Crescent in Bath, Somerset.[62][63]

In August 2012, Cleese married English jewellery designer and former model Jennifer Wade in a ceremony on the Caribbean island of Mustique.[64]

In March 2015, in an interview with Der Spiegel, he was asked if he was religious. Cleese stated that he didn't think much of organised religion and said he was not committed to "anything except the vague feeling that there is something more going on than the materialist reductionist people think".[55]

Cleese has a passion for lemurs.[65][66] Following the 1997 comedy film Fierce Creatures, in which the ring-tailed lemur played a key role, he hosted the 1998 BBC documentary In the Wild: Operation Lemur with John Cleese, which tracked the progress of a reintroduction of black-and-white ruffed lemurs back into the Betampona Reserve in Madagascar. The project had been partly funded by Cleese's donation of the proceeds from the London premier of Fierce Creatures.[66][67] Cleese is quoted as saying, "I adore lemurs. They're extremely gentle, well-mannered, pretty and yet great fun ... I should have married one."[65]

The Bemaraha woolly lemur (Avahi cleesei), also known as Cleese's woolly lemur, is native to western Madagascar. The scientist who discovered the species named it after Cleese, mainly because of Cleese's fondness for lemurs and his efforts at protecting and preserving them. The species was first discovered in 1990 by a team of scientists from Zurich University led by Urs Thalmann, but was not formally described as a species until 11 November 2005.[68]

Filmography

Film

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Interlude | TV Publicist | |

| 1968 | The Bliss of Mrs. Blossom | Post office clerk | |

| 1969 | The Magic Christian | Mr. Dougdale (director in Sotheby's) | |

| 1969 | The Best House in London | Jones | Uncredited |

| 1970 | The Rise and Rise of Michael Rimmer | Pummer | Also writer |

| 1971 | And Now for Something Completely Different | Various roles | Also writer |

| 1971 | The Statue | Harry | |

| 1973 | Anyone For Sex? | Role of Sex Therapist | |

| 1974 | Romance with a Double Bass | Musician Smychkov | Also writer |

| 1975 | Monty Python and the Holy Grail | Various roles | Also writer |

| 1977 | The Strange Case of the End of Civilization as We Know It | Arthur Sherlock Holmes | Also writer |

| 1979 | Monty Python's Life of Brian | Various roles | Also writer |

| 1981 | The Great Muppet Caper | Neville | Cameo |

| 1981 | Time Bandits | Gormless Robin Hood | |

| 1982 | Privates on Parade | Major Giles Flack | |

| 1982 | Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl | Various roles | Concert film; also writer |

| 1983 | Yellowbeard | Harvey "Blind" Pew | |

| 1983 | Monty Python's The Meaning of Life | Various roles | Also writer |

| 1985 | Silverado | Langston | |

| 1986 | Clockwise | Mr. Stimpson | Evening Standard British Film Awards Peter Sellers Award for Comedy |

| 1988 | A Fish Called Wanda | Barrister Archie Leach | Also writer and executive producer BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role Nominated—Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay Nominated—BAFTA Award for Best Original Screenplay Nominated—Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy Nominated—Writers Guild of America Award for Best Original Screenplay |

| 1989 | Erik the Viking | Halfdan the Black | |

| 1989 | The Big Picture | Bartender | Cameo |

| 1990 | Bullseye! | Man on the Beach in Barbados Who Looks Like John Cleese | Cameo |

| 1991 | An American Tail: Fievel Goes West | Cat R. Waul | Voice |

| 1993 | Splitting Heirs | Raoul P. Shadgrind | |

| 1994 | Mary Shelley's Frankenstein | Professor Waldman | |

| 1994 | The Jungle Book | Dr. Julius Plumford | |

| 1994 | The Swan Princess | Jean-Bob | Voice |

| 1996 | The Wind in the Willows | Mr. Toad's Lawyer | Cameo |

| 1997 | Fierce Creatures | Rollo Lee | Also writer and producer |

| 1997 | George of the Jungle | An Ape Named 'Ape' | Voice |

| 1998 | In the Wild: Operation Lemur with John Cleese | Narrator | Documentary |

| 1999 | The Out-of-Towners | Mr. Mersault | |

| 1999 | The World Is Not Enough | R | |

| 2000 | Isn't She Great | Henry Marcus | |

| 2000 | The Magic Pudding | Albert The Magic Pudding | Voice |

| 2001 | Quantum Project | Alexander Pentcho | |

| 2001 | Here's Looking at You: The Evolution of the Human Face | Narrator | Documentary |

| 2001 | Rat Race | Donald P. Sinclair | |

| 2001 | Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone | Nearly Headless Nick | |

| 2002 | Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets | Nearly Headless Nick | |

| 2002 | Roberto Benigni's Pinocchio | The Talking Crickett | English dub |

| 2002 | Die Another Day | Q | |

| 2002 | The Adventures of Pluto Nash | James | |

| 2003 | Charlie's Angels: Full Throttle | Mr. Munday | |

| 2003 | Scorched | Charles Merchant | |

| 2003 | George of the Jungle 2 | An Ape Named 'Ape' | Voice |

| 2004 | Shrek 2 | King Harold | Voice |

| 2004 | Around the World in 80 Days | Grizzled Sergeant | |

| 2005 | Valiant | Mercury | Voice |

| 2006 | Charlotte's Web | Samuel the Sheep | Voice |

| 2006 | Man About Town | Dr. Primkin | |

| 2007 | Shrek the Third | King Harold | Voice |

| 2008 | Igor | Dr. Glickenstein | Voice |

| 2008 | The Day the Earth Stood Still | Dr. Barnhardt | |

| 2009 | The Pink Panther 2 | Chief-Inspector Charles Dreyfus | |

| 2009 | Planet 51 | Professor Kipple | Voice |

| 2010 | Spud | The Guv | |

| 2010 | Legend of the Guardians: The Owls of Ga'Hoole | Ghost | Voice |

| 2010 | Shrek Forever After | King Harold | Voice |

| 2011 | Beethoven's Christmas Adventure | Narrator | Voice |

| 2011 | The Big Year | Historical Montage Narrator | Voice |

| 2011 | Winnie the Pooh | Narrator | Voice |

| 2012 | God Loves Caviar | McCormick | |

| 2012 | A Liar's Autobiography: The Untrue Story of Monty Python's Graham Chapman | David Frost / Various roles | Voices |

| 2013 | The Last Impresario | Himself | Documentary |

| 2013 | The Croods | Story credit | |

| 2013 | Spud 2: The Madness Continues | The Guv | |

| 2013 | Planes | Bulldog | Voice |

| 2014 | Spud 3: Learning to Fly | The Guv | |

| 2015 | Absolutely Anything | Chief Alien | Voice |

| 2016 | Get Squirrely | Mr. Bellwood | Voice |

| 2016 | Trolls | King Gristle Sr. | Voice |

| 2017 | Charming | The Fairy Godmother | Voice |

| 2018 | Arctic Justice: Thunder Squad | Doc Walrus | Voice |

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1962–1963 | That Was the Week That Was | Writer | |

| 1966–1967 | The Frost Report | Various roles | 28 episodes; also writer |

| 1967 | At Last the 1948 Show | Various roles | 2 seasons; also writer |

| 1968 | How to Irritate People | Various roles | Television film; also writer |

| 1968 | The Avengers | Marcus Rugman | Episode: "Look – (Stop Me If You've Heard This One) But There Were These Two Fellers..." |

| 1969–1974 | Monty Python's Flying Circus | Various roles | 40 episodes; also co-creator and writer Nominated—BAFTA Television Award for Best Light Entertainment Performance (1970–1971) |

| 1971, 1974 | Sez Les | Various roles | 18 episodes |

| 1972 | Monty Python's Fliegender Zirkus | Various roles | 2 episodes; also co-creator and writer |

| 1973 | The Goodies | The Genie | Episode: "The Goodies and the Beanstalk" |

| 1973 | Comedy Playhouse | Sherlock Holmes | Episode: "Elementary, My Dear Watson" |

| 1975, 1979 | Fawlty Towers | Basil Fawlty | 12 episodes; also co-creator and writer Nominated—BAFTA Television Award for Best Light Entertainment Performance (1976, 1980) |

| 1977 | The Muppet Show | Himself | Episode: "John Cleese" |

| 1979 | Ripping Yarns | Passer-by | Episode: Golden Gordon |

| 1979 | Doctor Who | Art Lover | Episode: "City of Death" |

| 1980 | The Taming of the Shrew | Petruchio | Television film |

| 1980 | The Secret Policeman's Ball | Himself (host) | Television special |

| 1982 | Whoops Apocalypse | Lacrobat | 3 episodes |

| 1987 | Cheers | Dr. Simon Finch-Royce | Episode: "Simon Says" Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Guest Actor in a Comedy Series |

| 1988 | True Stories: Peace in our Time? | Neville Chamberlain | Television film |

| 1992 | Did I Ever Tell You How Lucky You Are? | Narrator (voice) | Television special |

| 1993 | Last of the Summer Wine | Neighbour | Episode: "Welcome to Earth" |

| 1998, 2001 | 3rd Rock from the Sun | Dr. Liam Neesam | 4 episodes Nominated—Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Guest Actor in a Comedy Series |

| 1999 | Casper & Mandrilaftalen | Various roles | Episode #2.2 |

| 2001 | The Human Face | Himself (host) | 4 episodes; also writer Nominated—Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Nonfiction Special |

| 2002 | Wednesday 9:30 (8:30 Central) | Red Lansing | 12 episodes |

| 2002 | Disney's House of Mouse | Narrator (voice) | 4 episodes |

| 2003–2004 | Will & Grace | Lyle Finster | Uncredited 6 episodes Nominated—Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Guest Actor in a Comedy Series |

| 2004 | Wine for the Confused | Himself (host) | Documentary; also writer |

| 2008 | Batteries Not Included | Himself (host) | 6 episodes |

| 2008 | We Are Most Amused | Himself (host) | Television special |

| 2010 | Entourage | Himself | Episode: "Lose Yourself" |

| 2012–2013 | Whitney | Dr. Grant | 2 episodes |

| 2014 | Over the Garden Wall | Quincy Endicott / Adelaide (voices) | 2 episodes |

| 2018 | Hold the Sunset[note 1][70] | Phil | 6 episodes |

| 2018 | Speechless | Martin | 2 episodes |

Video games

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Storybook Weaver | Narrator | Voice |

| 1998 | Starship Titanic | The Bomb | Voice Credited as Kim Bread |

| 2000 | 007 Racing | R | Voice |

| 2000 | 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64) | R | Voice |

| 2000 | 007: The World Is Not Enough (PS1) | R | Voice |

| 2003 | James Bond 007: Everything or Nothing | Q | Voice |

| 2004 | Time Troopers | Special Agent Wormold | Voice |

| 2004 | Trivial Pursuit: Unhinged | History | Voice |

| 2005 | Jade Empire | Sir Roderick | Voice |

| 2007 | Shrek the Third | King Harold | Voice |

| 2010 | Fable III | Jasper | Voice |

| 2012 | Smart As | The Narrator[71] | Voice |

| 2014 | The Elder Scrolls Online | Sir Cadwell | Voice |

| 2016 | Payday 2 | The Butler (Aldstone)[72] | Voice |

Radio credits

| Year | Title |

|---|---|

| 1964–1973 | I'm Sorry, I'll Read That Again |

| 1972 | I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue |

Stage

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–2011 | Spamalot | God | Voice |

| 2014 | Monty Python Live (Mostly) | Various roles | Also writer |

Television advertisements

| Year | Title | Role |

|---|---|---|

| 1970s | Royal Mail | Pirate / Sir Betty |

| 1975 | Texaco | Himself |

| 1978 | Accurist | Himself |

| 1980–82 | Sony | Himself |

| 1981 | Giroblauw (Netherlands) | Interviewer |

| 1982 | Postbank (Netherlands) | Himself |

| 1982 | EAC Multilist (Australia) | Estate agent |

| 1982 | American Express | Himself |

| 1980s | Compaq | Himself |

| 1980s | Planters Pretzels (Australia) | Himself |

| 1986 | Maxwell House | Himself |

| 1988 | Talking Pages | Man who wants to marry Princess |

| 1990–91 | Schweppes | Himself |

| 1991–94 | Magnavox | Himself |

| 1992–93 | Talking Pages | Colin |

| 1993 | Nestlé Milk Chocolate (Australia) | Himself |

| 1993 | Cellnet | Woman |

| 1993–95 | Health Education Authority (Smoking Quitline) | Himself |

| 1996 | Norwich Union Direct | Himself |

| 1996 | Tele Danmark (Denmark) | Himself |

| 1998 | Tostitos | French chef |

| 1998 | Lexus | Himself, voice only |

| 1998–99 | Sainsbury's | Himself |

| 1999 | Melba toast | Himself |

| 1999 | Artistdirect.com | Himself |

| 2001 | 007: Agent Under Fire | R |

| 2001–08 | Titleist | Ian MacCallister |

| 2002 | Little Tikes | Himself |

| 2002 | Heineken | Himself |

| 2003 | Westinghouse Unplugged vacuum cleaner | Himself |

| 2005 | Intel | Himself |

| 2006 | TBS | Himself |

| 2006 | TV Spielfilm (Germany) | Himself |

| 2006–08 | Kaupþing (Iceland) | Himself |

| 2008 | Bank Zachodni WBK (Poland) | Himself |

| 2009 | Elgiganten (Sweden) | Himself |

| 2009 | Hashahar Ha'oleh (Israel) | Western general |

| 2009 | Accurist | Himself |

| 2010 | William Hill (Austria) | Himself |

| 2010–11 | AA | Himself |

| 2011 | Dogtober (Australia) | Himself, voice only |

| 2012 | Czech Olympic Team (Czech Republic) | Himself |

| 2012 | DirecTV | Himself |

| 2012 | Canadian Club (Australia) | Himself, voice only |

| 2015 | Specsavers | Basil Fawlty |

Honours and tributes

- A species of lemur, the Bemaraha woolly lemur (Avahi cleesei), has been named in his honour. John Cleese has mentioned this in television interviews. Also there is mention of this honour in "New Scientist"—and John Cleese's response to the honour.[73]

- An asteroid, 9618 Johncleese, is named in his honour.

- Cleese declined a CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in 1996.

- There is a municipal rubbish heap of 45 metres (148 ft) in altitude that has been named Mt Cleese at the Awapuni landfill just outside Palmerston North after he dubbed the city "suicide capital of New Zealand" after a stay there in 2005.[74][75]

- "The Universal Language" skit from All in the Timing, a collection of short plays by David Ives, centres around a fictional language (Unamunda) in which the word for the English language is "johncleese".

- The post-hardcore rock band I Set My Friends on Fire has a song on their You Can't Spell Slaughter Without Laughter album titled "Reese's Pieces, I Don't Know Who John Cleese Is?".

Scholastic

- University Degrees

| Location | Date | School | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | Downing College, Cambridge | Law Degree |

- Chancellor, visitor, governor, rector, and fellowships

| Location | Date | School | Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 – 1973 | University of St Andrews | Rector |

- Honorary Degrees

| Location | Date | School | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | University of St Andrews | Doctorate | |

| 28 June 2016 | University of Bath | Doctor of Clinical Psychology [76][77] | |

| 17 September 2016 | Open University | Doctor of the University (D. Univ) [78][79] |

Bibliography

The Rectorial Address of John Cleese, Epam, 1971, 8 pages

Cleese Encounters: The Unauthorized Biography of Monty Python Veteran John Cleese, Jonathan Margolis, St. Martin's Press, 1992, .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 0-312-08162-6

The Human Face (with Brian Bates) (DK Publishing Inc., 2001,

ISBN 978-0-7894-7836-8)- Foreword for Time and the Soul, Jacob Needleman, 2003,

ISBN 1-57675-251-8 (paperback)

Superman: True Brit, DC Comics, 2004,

ISBN 9781845760120

So, Anyway..., 2014, Crown Archetype,

ISBN 038534824X

Professor at Large: The Cornell Years, 2018, Cornell University Press,

ISBN 978-1-5017-1657-7

Dialogues

Families and How to Survive Them, w/Robin Skynner, 1983

ISBN 0-413-52640-2 (hardc.),

ISBN 0-19-520466-2 (p/back)

Life and How to Survive It, w/Robin Skynner 1993

ISBN 0-413-66030-3 (hardcover),

ISBN 0-393-31472-3 (paperback)

See also

- List of people who have declined a British honour

Notes

^ Previously named Edith[69]

References

^ "John Cleese Biography (1939–)". Filmreference.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

^ Stadlen, Matthew (13 October 2014). "John Cleese says: 'I've finally found true love – in a fish and three cats'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 5 November 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

^ Raphael, Amy (29 November 2008). "Ross and Brand were astoundingly tasteless". The Guardian. London, England: Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

^ "The Bristol Funny List: 50 of the city's funniest men and women". Bristol Live. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

^ "WTF with Marc Maron Podcast: Episode 961 - John Cleese". wtfpod.libsyn.com. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

^ "San Diego Magazine, Silly Walks and Dead Parrots". Sandiegomag.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

^ "John Cleese". Cardinal Fang's Python Site. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

^ "John Cleese". Leading Authorities. Archived from the original on 10 September 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

^ abcdefghijk From Fringe to Flying Circus – 'Celebrating a Unique Generation of Comedy 1960–1980' – Roger Wilmut, Eyre Methuen Ltd, 1980,

ISBN 0-413-46950-6.

^ "John Cleese to Spend Five Years Tour As Professor at Cornell University". Daily Llama. 18 January 1999. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

^ Life of Brian commentary by Terry Jones, Terry Gilliam and Eric Idle

^ abc Footlights! – 'A Hundred Years of Cambridge Comedy' – Robert Hewison, Methuen London Ltd, 1983,

ISBN 0-413-51150-2.

^ Sunday Times, 16 October 1988.

^ Cleese, John (2014). New York: Crown Archetype, p. 318.

^ P70, The Authorised History of I'm Sorry I Haven't A Clue; Jem Roberts

ISBN 978-1-84809-132-0

^ Morris Bright; Robert Ross (2001). Fawlty Towers: fully booked. BBC. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-563-53439-6. Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

^ "List of Rectors of University of St. Andrews". Archived from the original on 14 January 2005. Retrieved 18 August 2013.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ "John Cleese Biography". Cardinal fang. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

^ Andy Lowe. "30 Things You Genuinely Never Knew About John Cleese". Bubblegun.com. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

^ "Why we'll never know the real Les Dawson : Correspondents 2008 : Chortle : The UK Comedy Guide". Chortle. 15 January 2008. Archived from the original on 5 November 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

^ ab Milmo, Cahal (25 May 2007). "Life after Polly: Connie Booth (a case of Fawlty memory syndrome)". Independent. Archived from the original on 2 May 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

^ Garlen, Jennifer C.; Graham, Anissa M. (2009). Kermit Culture: Critical Perspectives on Jim Henson's Muppets. McFarland & Company. p. 218. ISBN 0-7864-4259-X.

^ "John Cleese – Episode 47". Muppet Central. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

^ "John Cleese". Save me a ticket. Archived from the original on 9 April 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

^ "YouTube – John Cleese Explains Proportional Representation for Canada & Ontario changes Coming". Topix. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

^ Cleese continued to openly say the word, most notably reported in an interview hosted by Robert Klein, in which Cleese remarked that Chapman is "stone-fucking-dead!"Memorial eulogy by John Cleese for Graham Chapman Archived 1 August 2012 at Archive.is

^ "Restaurant review: Michael Winner at Villa Principe Leopoldo, Switzerland". The Sunday Times. UK. 6 July 2008. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

^ Cowsill, Alan; Dolan, Hannah, ed. (2010). "2000s". DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. Dorling Kindersley. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9.Comedy legend John Cleese joined forces with artist John Byrne, inker Mark Farmer and writer Kim Johnson for a unique take on the Superman story. Superman: True Brit saw Kal-El's rocketship land on a farm ... in the UK.

CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ "John Cleese Brings Seven Ways to Skin an Ocelot to U.S." Playbill. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

^ "Art of Soccer, The With John Cleese". Bfsent.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

^ "The real reason I had to join". The Spectator. UK. 25 March 2009. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

^ Ottosen, Peder. "John Cleese i Elkjøp-reklame". Kjendis.no. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

^ Brudvig, Erik (11 March 2010). "GDC 10: Designing Fable III – Xbox 360 Preview at IGN". Xbox360.ign.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

^ "BBC – Ex-Python John Cleese goes on first UK tour, aged 71". BBC News. 20 May 2010. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

^ Oatts, Joanne. "AA ad features John Cleese at". Marketing Week. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

^ "Canadian Marketing Association Awards 2010" (PDF). Canadian Marketing Association. November 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

^ "Pacific Blue Cross gets Comedic Insurance with John Cleese". Wave Productions. 1 April 2010. Archived from the original on 1 January 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

^ Anderman, Irit (17 May 2012). "British actor John Cleese to appear in Israeli heist comedy". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

^ Roxborough, Scott (16 May 2012). "Cannes 2012: John Cleese Joins Israeli Comedy 'Hunting Elephants'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

^ "Cleese replaced by Stewart". Archived from the original on 20 November 2012.

^ Chamberlain, Adrian (9 October 2013). "John Cleese, the minister of silly talks, sure has a big following". Times Colonist. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013.

^ Hymers, Sarah (6 November 2013). "John Cleese in Dubai". Ahlan!. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013.

^ Coveney, Michael (9 March 2016). "Michael White obituary". Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

^ Ng, David (21 November 2013). "Monty Python makes it official: group reuniting in July". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013.

^ "I am John Cleese: writer, actor, and tall person. AMA!". Reddit. Archived from the original on 24 November 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

^ "I blame my mother for my fawlty love life, says John Cleese". Daily Express.

^ Connolly, Nancy (4 May 2015). "Actor, comedian and former Bath resident John Cleese lends his weight (and height) to Bath Lib Dems". Bath Chronicle. Archived from the original on 12 October 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

^ "Lib Dems plan warmer homes". BBC News. 31 May 2001. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

^ "'Monty Python' icon John Cleese stumps to be Barack Obama's speechwriter". Daily News. New York. 9 April 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

^ Cleese, John; Pedersen, Erik (14 October 2008). "John Cleese: Sarah Palin Funnier Than Michael Palin". E!. Archived from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

^ "John Cleese Destroys Sean Hannity with Poetry" Archived 12 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Daily Kos.

^ Walker, Tim (25 January 2011). "David Cameron impresses John Cleese with his good manners". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016.

^ Nikkhah, Roya (17 April 2011). "Lord Cleese of Fawlty Towers: Why John Cleese declined a peerage". The Sunday Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 April 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

^ ab Stadlen, Matthew (13 October 2014). "John Cleese says: 'I've finally found true love – in a fish and three cats'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 5 November 2015.

^ ab SPIEGEL Interview with John Cleese: 'Satire Makes People Think' Archived 26 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 31 March 2015

^ Saul, Heather (25 June 2016). "Brexit: The famous figures celebrating the EU referendum result". The Independent.

^ "John Cleese set to move to the Caribbean over 'disappointment' with UK". London Evening Standard.

^ "Donald Trump narcissist with no attention span, says John Cleese". The Belfast Telegraph. 11 October 2016.

^ abc McVey, Dominic; Stapleton, John (September 2000). "Can anti-smoking television advertising affect smoking behaviour? controlled trial of the Health Education Authority for England's anti-smoking TV campaign". Tob Control. 9 (3): 273–82. doi:10.1136/tc.9.3.273. PMC 1748378. PMID 10982571. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

^ "John Cleese". Nndb.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

^ Pierce, Andrew (18 August 2009). "John Cleese in £12 million divorce settlement". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

^ "John Cleese on move to 'beautiful' Georgian Bath". BBC News. 17 August 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

^ "John Cleese could be spending more time in Bath after selling His Monaco des res". Southwest Business. 18 March 2013. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013.

^ Singh, Anita (2012-08-13). "John Cleese marries for the fourth time". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

^ ab Hans ten Cate (13 June 2002). "John Cleese Visits Lemurs at San Francisco Zoo". PythOnline's Daily Llama. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

^ ab John Cleese (host) (1998). In the Wild: Operation Lemur with John Cleese (DVD). Tigress Productions Ltd for BBC. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

^ "Four More Lemurs To Be Released into Madagascar Jungle This Fall". Science Daily. Duke University. 12 October 1998. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

^ "Endangered lemurs get Fawlty name". BBC. 11 November 2005. Archived from the original on 4 February 2010.

^ "Edith". Archived from the original on 1 May 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

^ "Hold the Sunset". Retrieved 14 February 2018.

^ David Hinkle (14 August 2012). "John Cleese to crack wise in Smart As". Joystiq. Archived from the original on 25 May 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

^ Overkill Software (6 October 2016). "PAYDAY 2: Hoxton's Housewarming Party Trailer". YouTube. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016.

^ Cleese, John (3 December 2005). "Monty Python's lemur". New Scientist (2528). Archived from the original on 6 February 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

^ Funnyman Cleese rubbishes NZ city Archived 10 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.. The Australian, 21 May 2007

^ "Palmerston North's heap of payback on Cleese". 21 May 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2018 – via www.nzherald.co.nz.

^ https://www.bath.ac.uk/announcements/university-honours-john-cleese/

^ https://www.bath.ac.uk/corporate-information/john-cleese-oration/

^ http://www.open.ac.uk/students/ceremonies/sites/www.open.ac.uk.students.ceremonies/files/files/Honorary_graduate_cumulative_list_2017.pdf

^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IlU2d7XUxCI

Published works

Cleese, John (2014). So, Anyway... Crown Archetype. ISBN 978-0-385-34824-9.

Cleese, John (2018). Professor at Large: The Cornell Years. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-1657-7.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Cleese |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Cleese. |

- Official website

John Cleese at the Museum of Broadcast Communications

John Cleese at the BBC Guide to Comedy

John Cleese on IMDb

John Cleese at the Internet Broadway Database

John Cleese on Charlie Rose

"John Cleese collected news and commentary". The Guardian.

"John Cleese collected news and commentary". The New York Times.

Works by or about John Cleese in libraries (WorldCat catalog)- Podcast to celebrate The Life of Brian (March 2008)

- Daily Llama: John Cleese Visits Lemurs at San Francisco Zoo

2014 John Cleese interview with Jon Niccum, Kansas City Star

- John Cleese Speaking at the American School in London

| Preceded by Desmond Llewelyn 1963–1999 | Q (James Bond Character) 2002 | Succeeded by Ben Whishaw |

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Learie Nicholas Constantine, Baron Constantine, Kt. | Rector of the University of St Andrews 1970–1973 | Succeeded by Alan Coren |