Bastille

| Bastille | |

|---|---|

| Paris, France | |

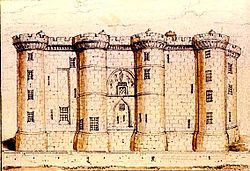

East view of the Bastille, drawing c. 1790 | |

Bastille | |

| Coordinates | 48°51′12″N 2°22′09″E / 48.853333°N 2.369167°E / 48.853333; 2.369167Coordinates: 48°51′12″N 2°22′09″E / 48.853333°N 2.369167°E / 48.853333; 2.369167 |

| Type | Medieval fortress, prison |

| Site information | |

| Condition | Destroyed, limited stonework survives |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1370–1380s |

| Built by | Charles V of France |

| Demolished | 1789–90 |

| Events | Hundred Years' War Wars of Religion Fronde French Revolution |

The Bastille (/bæˈstiːl/; French pronunciation: [bastij]) was a fortress in Paris, known formally as the Bastille Saint-Antoine. It played an important role in the internal conflicts of France and for most of its history was used as a state prison by the kings of France. It was stormed by a crowd on 14 July 1789, in the French Revolution, becoming an important symbol for the French Republican movement, and was later demolished and replaced by the Place de la Bastille.

The Bastille was built to defend the eastern approach to the city of Paris from the English threat in the Hundred Years' War. Initial work began in 1357, but the main construction occurred from 1370 onwards, creating a strong fortress with eight towers that protected the strategic gateway of the Porte Saint-Antoine on the eastern edge of Paris. The innovative design proved influential in both France and England and was widely copied. The Bastille figured prominently in France's domestic conflicts, including the fighting between the rival factions of the Burgundians and the Armagnacs in the 15th century, and the Wars of Religion in the 16th. The fortress was declared a state prison in 1417; this role was expanded first under the English occupiers of the 1420s and 1430s, and then under Louis XI in the 1460s. The defences of the Bastille were fortified in response to the English and Imperial threat during the 1550s, with a bastion constructed to the east of the fortress. The Bastille played a key role in the rebellion of the Fronde and the battle of the faubourg Saint-Antoine, which was fought beneath its walls in 1652.

Louis XIV used the Bastille as a prison for upper-class members of French society who had opposed or angered him including, after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, French Protestants. From 1659 onwards, the Bastille functioned primarily as a state penitentiary; by 1789, 5,279 prisoners had passed through its gates. Under Louis XV and XVI, the Bastille was used to detain prisoners from more varied backgrounds, and to support the operations of the Parisian police, especially in enforcing government censorship of the printed media. Although inmates were kept in relatively good conditions, criticism of the Bastille grew during the 18th century, fueled by autobiographies written by former prisoners. Reforms were implemented and prisoner numbers were considerably reduced. In 1789 the royal government's financial crisis and the formation of the National Assembly gave rise to a swelling of republican sentiments among city-dwellers. On 14 July the Bastille was stormed by a revolutionary crowd, primarily residents of the faubourg Saint-Antoine who sought to commandeer the valuable gunpowder held within the fortress. Seven remaining prisoners were found and released and the Bastille's governor, Bernard-René de Launay, was killed by the crowd. The Bastille was demolished by order of the Committee of the Hôtel de Ville. Souvenirs of the fortress were transported around France and displayed as icons of the overthrow of despotism. Over the next century, the site and historical legacy of the Bastille featured prominently in French revolutions, political protests and popular fiction, and it remained an important symbol for the French Republican movement.

Almost nothing is left of the Bastille except some remains of its stone foundation that were relocated to the side of Boulevard Henri IV. Historians were critical of the Bastille in the early 19th century, and believe the fortress to have been a relatively well-administered institution, but deeply implicated in the system of French policing and political control during the 18th century.

.mw-parser-output .toclimit-2 .toclevel-1 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-3 .toclevel-2 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-4 .toclevel-3 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-5 .toclevel-4 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-6 .toclevel-5 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-7 .toclevel-6 ul{display:none}

Contents

1 History

1.1 14th century

1.2 15th century

1.3 16th century

1.4 Early 17th century

1.5 Reign of Louis XIV and the Regency (1661–1723)

1.6 Reigns of Louis XV and Louis XVI (1723–1789)

1.6.1 Architecture and organisation

1.6.2 Use of the prison

1.6.3 Prison regime

1.6.4 Criticism and reform

1.7 The French Revolution

1.7.1 Storming of the Bastille

1.7.2 Destruction

1.8 19th–20th century political and cultural legacy

2 Remains

3 Historiography

4 See also

5 Notes

5.1 Footnotes

5.2 Citations

6 References

7 External links

History

14th century

Historical reconstruction showing the moat below the walls of Paris (left), the Bastille and the Porte Saint-Antoine (right) in 1420

The Bastille was built in response to a threat to Paris during the Hundred Years' War between England and France.[1] Prior to the Bastille, the main royal castle in Paris was the Louvre, in the west of the capital, but the city had expanded by the middle of the 14th century and the eastern side was now exposed to an English attack.[1] The situation worsened after the imprisonment of John II in England following the French defeat at the battle of Poitiers, and in his absence the Provost of Paris, Étienne Marcel, took steps to improve the capital's defences.[2] In 1357, Marcel expanded the city walls and protected the Porte Saint-Antoine with two high stone towers and a 78-foot-wide (24 m) ditch.[3][A] A fortified gateway of this sort was called a "bastille", and was one of two created in Paris, the other being built outside the Porte Saint-Denis.[5] Marcel was subsequently removed from his post and executed in 1358.[6]

In 1369, Charles V became concerned about the weakness of the eastern side of the city to English attacks and raids by mercenaries.[7] Charles instructed Hugh Aubriot, the new provost, to build a much larger fortification on the same site as Marcel's bastille.[6] Work began in 1370 with another pair of towers being built behind the first bastille, followed by two towers to the north, and finally two towers to the south.[8] The fortress was probably not finished by the time Charles died in 1380, and was completed by his son, Charles VI.[8] The resulting structure became known simply as the Bastille, with the eight irregularly built towers and linking curtain walls forming a structure 223 feet (68 m) wide and 121 feet (37 m) deep, the walls and towers 78 feet (24 m) high and 10 feet (3.0 m) thick at their bases.[9] Built to the same height, the roofs of the towers and the tops of the walls formed a broad, crenellated walkway all the way around the fortress.[10] Each of the six newer towers had underground "cachots", or dungeons, at its base, and curved "calotte", literally "shell", rooms in their roofs.[11]

Garrisoned by a captain, a knight, eight squires and ten crossbowmen, the Bastille was encircled with ditches fed by the River Seine, and faced with stone.[12] The fortress had four sets of drawbridges, which allowed the Rue Saint-Antoine to pass eastwards through the Bastille's gates while giving easy access to the city walls on the north and south sides.[13] The Bastille overlooked the Saint-Antoine gate, which by 1380 was a strong, square building with turrets and protected by two drawbridges of its own.[14] Charles V chose to live close to the Bastille for his own safety and created a royal complex to the south of the fortress called the Hôtel St. Paul, stretching from the Porte Saint-Paul up to the Rue Saint-Antoine.[15][B]

Historian Sidney Toy has described the Bastille as "one of the most powerful fortifications" of the period, and the most important fortification in late medieval Paris.[16] The Bastille's design was highly innovative: it rejected both the 13th-century tradition of more weakly fortified quadrangular castles, and the contemporary fashion set at Vincennes, where tall towers were positioned around a lower wall, overlooked by an even taller keep in the centre.[10] In particular, building the towers and the walls of the Bastille at the same height allowed the rapid movement of forces around the castle, as well as giving more space to move and position cannons on the wider walkways.[17] The Bastille design was copied at Pierrefonds and Tarascon in France, while its architectural influence extended as far as Nunney Castle in south-west England.[18]

15th century

Parisian defences in 14th century: A – the Louvre; B – Palais de Roi; C – Hôtel des Tournelles; D – Porte Saint-Antoine; E – Hôtel St Paul; F – the Bastille

During the 15th century the French kings continued to face threats both from the English and from the rival factions of the Burgundians and the Armagnacs.[19] The Bastille was strategically vital during the period, both because of its role as a royal fortress and safe-haven inside the capital, and because it controlled a critical route in and out of Paris.[20] In 1418, for example, the future Charles VII took refuge in the Bastille during the Burgundian-led "Massacre of the Armagnacs" in Paris, before successfully fleeing the city through the Porte Saint-Antoine.[21]

The Bastille was occasionally used to hold prisoners, including its creator, Hugues Aubriot, who was the first person to be imprisoned there. In 1417, in addition to being a royal fortress, it formally became a state prison.[22][C]

Despite the improved Parisian defences, Henry V of England captured Paris in 1420 and the Bastille was seized and garrisoned by the English for the next sixteen years.[22] Henry V appointed Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter, as the new captain of the Bastille.[22] The English made more use of the Bastille as a prison; in 1430 there was a minor rebellion when some prisoners overpowered a sleeping guard and attempted to seize control of the fortress; this incident includes the first reference to a dedicated gaoler at the Bastille.[24]

Paris was finally recaptured by Charles VII of France in 1436. When the French king re-entered the city, his enemies in Paris fortified themselves in the Bastille; after a siege, they eventually ran out of food, surrendered and were allowed to leave the city after the payment of a ransom.[25] The castle remained a key Parisian fortress, but was successfully seized by the Burgundians in 1464, when they convinced royal troops to surrender: once taken, this allowed their faction to make a surprise attack into Paris, almost resulting in the capture of the king.[26]

The Bastille was being used to hold prisoners once again by the reign of Louis XI, who began to use it extensively as a state penitentiary.[27] An early escapee from the Bastille during this period was Antoine de Chabannes, Count of Dammartin and a member of the League of the Public Weal, who was imprisoned by Louis and escaped by boat in 1465.[28] The captains of the Bastille during this period were primarily officers and royal functionaries; Philippe de Melun was the first captain to receive a salary in 1462, being awarded 1,200 livres a year.[29][D] Despite being a state prison, the Bastille retained the other traditional functions of a royal castle, and was used to accommodate visiting dignitaries, hosting some lavish entertainments given by Louis XI and Francis I.[31]

16th century

A depiction of the Bastille and neighbouring Paris in 1575, showing the new bastions, the new Porte Saint-Antoine, the Arsenal complex and the open countryside beyond the city defences

During the 16th century the area around the Bastille developed further. Early modern Paris continued to grow, and by the end of the century it had around 250,000 inhabitants and was one of the most populous cities in Europe, though still largely contained within its old city walls – open countryside remained beyond the Bastille.[32] The Arsenal, a large military-industrial complex tasked with the production of cannons and other weapons for the royal armies, was established to the south of the Bastille by Francis I, and substantially expanded under Charles IX.[33] An arms depot was later built above the Porte Saint-Antoine, all making the Bastille part of a major military centre.[34]

During the 1550s, Henry II became concerned about the threat of an English or Holy Roman Empire attack on Paris, and strengthened the defences of the Bastille in response.[35] The southern gateway into the Bastille became the principal entrance to the castle in 1553, the other three gateways being closed.[22] A bastion, a large earthwork projecting eastwards from the Bastille, was built to provide additional protective fire for the Bastille and the Arsenal; the bastion was reached from the fortress across a stone abutment using a connecting drawbridge that was installed in the Bastille's Comté tower.[36] In 1573 the Porte Saint-Antoine was also altered – the drawbridges were replaced with a fixed bridge, and the medieval gatehouse was replaced with a triumphal arch.[37]

The Bastille in 1647, illustrating the bastion, the stone abutment linking to the fortress and the new southern entrance built during the 1550s

The Bastille was involved in the numerous wars of religion fought between Protestant and Catholic factions with support from foreign allies during the second half of the 16th century. Religious and political tensions in Paris initially exploded in the Day of the Barricades on 12 May 1588, when hard-line Catholics rose up in revolt against the relatively moderate Henry III. After a day's fighting had occurred across the capital, Henry III fled and the Bastille surrendered to Henry, the Duke of Guise and leader of the Catholic League, who appointed Bussy-Leclerc as his new captain.[38] Henry III responded by having the Duke and his brother murdered later that year, whereupon Bussy-Leclerc used the Bastille as a base to mount a raid on the Parlement de Paris, arresting the president and other magistrates, whom he suspected of having royalist sympathies, and detaining them in the Bastille.[39] They were not released until the intervention of Charles, the Duke of Mayenne, and the payment of substantial ransoms.[40] Bussy-Leclerc remained in control of the Bastille until December 1592, when, following further political instability, he was forced to surrender the castle to Charles and flee the city.[41]

It took Henry IV several years to retake Paris. By the time he succeeded in 1594, the area around the Bastille formed the main stronghold for the Catholic League and their foreign allies, including Spanish and Flemish troops.[42] The Bastille itself was controlled by a League captain called du Bourg.[43] Henry entered Paris early on the morning of 23 March, through the Porte-Neuve rather than the Saint-Antoine and seized the capital, including the Arsenal complex that neighboured the Bastille.[44] The Bastille was now an isolated League stronghold, with the remaining members of the League and their allies clustering around it for safety.[45] After several days of tension, an agreement was finally reached for this rump element to leave safely, and on 27 March du Bourg surrendered the Bastille and left the city himself.[46]

Early 17th century

A contemporary depiction of the battle of the Faubourg St Antoine beneath the walls of the Bastille in 1652

The Bastille continued to be used as a prison and a royal fortress under both Henry IV and his son, Louis XIII. When Henry clamped down on a Spanish-backed plot among the senior French nobility in 1602, for example, he detained the ringleader Charles Gontaut, the Duke of Biron, in the Bastille, and had him executed in the courtyard.[47] Louis XIII's chief minister, Cardinal Richelieu, is credited with beginning the modern transformation of the Bastille into a more formal organ of the French state, further increasing its structured use as a state prison.[48] Richelieu broke with Henry IV's tradition of the Bastille's captain being a member of the French aristocracy, typically a Marshal of France such as François de Bassompierre, Charles d'Albert or Nicolas de L'Hospital, and instead appointed Père Joseph's brother to run the facility.[49][E] The first surviving documentary records of prisoners at the Bastille also date from this period.[51]

In 1648, the Fronde insurrection broke out in Paris, prompted by high taxes, increased food prices and disease.[52] The Parlement of Paris, the Regency government of Anne of Austria and rebellious noble factions fought for several years to take control of the city and wider power. On 26 August, during the period known as the First Fronde, Anne ordered the arrest of some of the leaders of the Parlement of Paris; violence flared as a result, and the 27 August became known as another Day of the Barricades.[53] The governor of the Bastille loaded and readied his guns to fire on the Hôtel de Ville, controlled by the parliament, although the decision was eventually taken not to shoot.[54] Barricades were erected across the city and the royal government fled in September, leaving a garrison of 22 men behind in the Bastille.[55] On 11 January 1649, the Fronde decided to take the Bastille, giving the task to Elbeuf, one of their leaders.[56] Elbeuf's attack required only a token effort: five or six shots were fired at the Bastille, before it promptly surrendered on the 13 January.[57]Pierre Broussel, one of the Fronde leaders, appointed his son as the governor and the Fronde retained it even after the ceasefire that March.[58]

The Bastille and the eastern side of Paris in 1649

During the Second Fronde, between 1650 and 1653, Louis, the Prince of Condé, controlled much of Paris alongside the Parlement, while Broussel, through his son, continued to control the Bastille. In July 1652, the battle of the Faubourg St Antoine took place just outside the Bastille. Condé had sallied out of Paris to prevent the advance of the royalist forces under the command of Turenne.[59] Condé's forces became trapped against the city walls and the Porte Saint-Antoine, which the Parlement refused to open; he was coming under increasingly heavy fire from the Royalist artillery and the situation looked bleak.[60] In a famous incident, La Grande Mademoiselle, the daughter of Gaston, the Duke of Orléans, convinced her father to issue an order for the Parisian forces to act, before she then entered the Bastille and personally ensured that the commander turned the fortress's cannon on Turenne's army, causing significant casualties and enabling Condé's army's safe withdrawal.[61] Later in 1652, Condé was finally forced to surrender Paris to the royalist forces in October, effectively bringing the Fronde to an end: the Bastille returned to royal control.[52]

Reign of Louis XIV and the Regency (1661–1723)

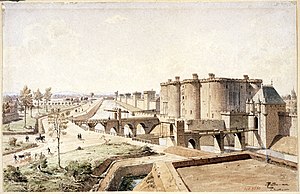

The Bastille and Porte Saint-Antoine from the north-east, 1715–19

The area around the Bastille was transformed in the reign of Louis XIV. Paris' growing population reached 400,000 during the period, causing the city to spill out past the Bastille and the old city into the arable farmland beyond, forming more thinly populated "faubourgs", or suburbs.[62] Influenced by the events of the Fronde, Louis XIV rebuilt the area around the Bastille, erecting a new archway at the Porte Saint-Antoine in 1660, and then ten years later pulling down the city walls and their supporting fortifications to replace them with an avenue of trees, later called Louis XIV's boulevard, which passed around the Bastille.[63] The Bastille's bastion survived the redevelopment, becoming a garden for the use of the prisoners.[64]

Louis XIV made extensive use of the Bastille as a prison, with 2,320 individuals being detained there during his reign, approximately 43 a year.[65] Louis used the Bastille to hold not just suspected rebels or plotters but also those who had simply irritated him in some way, such as differing with him on matters of religion.[66] The typical offences that inmates were accused of were espionage, counterfeiting and embezzlement from the state; a number of financial officials were detained in this way under Louis, most famously including Nicolas Fouquet, his supporters Henry de Guénegaud, Jeannin and Lorenzo de Tonti.[67] In 1685 Louis revoked the Edict of Nantes, which had previously granted various rights to French Protestants; the subsequent royal crackdown was driven by the king's strongly anti-Protestant views.[68] The Bastille was used to investigate and break up Protestant networks by imprisoning and questioning the more recalcitrant members of the community, in particular upper-class Calvinists; some 254 Protestants were imprisoned in the Bastille during Louis's reign.[69]

By Louis's reign, Bastille prisoners were detained using a "lettre de cachet", "a letter under royal seal", issued by the king and countersigned by a minister, ordering a named person to be held.[70] Louis, closely involved in this aspect of government, personally decided who should be imprisoned at the Bastille.[65] The arrest itself involved an element of ceremony: the individual would be tapped on the shoulder with a white baton and formally detained in the name of the king.[71] Detention in the Bastille was typically ordered for an indefinite period and there was considerable secrecy over who had been detained and why: the legend of the "Man in the Iron Mask", a mysterious prisoner who finally died in 1703, symbolises this period of the Bastille.[72] Although in practice many were held at the Bastille as a form of punishment, legally a prisoner in the Bastille was only being detained for preventative or investigative reasons: the prison was not officially supposed to be a punitive measure in its own right.[73] The average length of imprisonment in the Bastille under Louis XIV was approximately three years.[74]

The Bastille in 1734, showing the Louis XIV boulevard and the growing "faubourg" beyond the Porte Saint-Antoine

Under Louis, only between 20 and 50 prisoners were usually held at the Bastille at any one time, although as many as 111 were held for a short period in 1703.[70] These prisoners were mainly from the upper classes, and those who could afford to pay for additional luxuries lived in good conditions, wearing their own clothes, living in rooms decorated with tapestries and carpets or taking exercise around the castle garden and along the walls.[73] By the late 17th century, there was a rather disorganised library for the use of inmates in the Bastille, although its origins remain unclear.[75][F]

Louis reformed the administrative structure of the Bastille, creating the post of governor, although this post was still often referred to as the captain-governor.[77] During Louis's reign the policing of marginal groups in Paris was greatly increased: the wider criminal justice system was reformed, controls over printing and publishing extended, new criminal codes were issued and the post of the Parisian lieutenant general of police was created in 1667, all of which would enable the Bastille's later role in support of the Parisian police during the 18th century.[78] By 1711, a 60-strong French military garrison had been established at the Bastille.[79] It continued to be an expensive institution to run, particularly when the prison was full, such as during 1691 when numbers were inflated by the campaign against French Protestants and the annual cost of running the Bastille rose to 232,818 livres.[80][G]

Between 1715 – the year of Louis's death – and 1723, power transferred to the Régence; the regent, Philippe d'Orléans, maintained the prison but the absolutist rigour of Louis XIV's system began to weaken somewhat.[82] Although Protestants ceased to be kept in the Bastille, the political uncertainties and plots of the period kept the prison busy and 1,459 were imprisoned there under the Regency, an average of around 182 a year.[83] During the Cellamare Conspiracy, the alleged enemies of the Regency were imprisoned in the Bastille, including Marguerite De Launay.[84] While in the Bastille, de Launay fell in love with a fellow prisoner, the Chevalier de Ménil; she also infamously received an invitation of marriage from the Chevalier de Maisonrouge, the governor's deputy, who had fallen in love with her himself.[84]

Reigns of Louis XV and Louis XVI (1723–1789)

Architecture and organisation

A cross-section of the Bastille viewed from the south in 1750

By the late 18th century, the Bastille had come to separate the more aristocratic quarter of Le Marais in the old city from the working class district of the faubourg Saint-Antoine that lay beyond the Louis XIV boulevard.[65] The Marais was a fashionable area, frequented by foreign visitors and tourists, but few went beyond the Bastille into the faubourg.[85] The faubourg was characterised by its built-up, densely populated areas, particularly in the north, and its numerous workshops producing soft furnishings.[86] Paris as a whole had continued to grow, reaching slightly less than 800,000 inhabitants by the reign of Louis XVI, and many of the residents around the faubourg had migrated to Paris from the countryside relatively recently.[87] The Bastille had its own street address, being officially known as No. 232, rue Saint-Antoine.[88]

Structurally, the late-18th century Bastille was not greatly changed from its 14th-century predecessor.[89] The eight stone towers had gradually acquired individual names: running from the north-east side of the external gate, these were La Chapelle, Trésor, Comté, Bazinière, Bertaudière, Liberté, Puits and Coin.[90] La Chapelle contained the Bastille's chapel, decorated with a painting of Saint Peter in chains.[91] Trésor took its name from the reign of Henry IV, when it had contained the royal treasury.[92] The origins of the name of Comté tower are unclear; one theory is that the name refers to the County of Paris.[93] Bazinière was named after Bertrand de La Bazinière, a royal treasurer who was imprisoned there in 1663.[92] Bertaudière was named after a medieval mason who died building the structure in the 14th century.[94] Liberté tower took its name either from a protest in 1380, when Parisians shouted the phrase outside the castle, or because it was used to house prisoners who had more freedom to walk around the castle than the typical prisoner.[95] Puits tower contained the castle well, while Coin formed the corner of the Rue Saint-Antoine.[94]

Plan of the Bastille in the 18th century. A – La Chapelle Tower; B – Trésor Tower; C – Comté Tower; D – Bazinière Tower; E – Bertaudière Tower; F – Liberté Tower; G – Puits Tower; H – Coin Tower; I – Courtyard of the Well; J – Office wing; K – Large Courtyard

The main castle courtyard, accessed through the southern gateway, was 120 feet long by 72 feet wide (37 m by 22 m), and was divided from the smaller northern yard by a three-office wing, built around 1716 and renovated in 1761 in a modern, 18th-century style.[96] The office wing held the council room that was used for interrogating prisoners, the Bastille's library, and servants' quarters.[97] The upper stories included rooms for the senior Bastille staff, and chambers for distinguished prisoners.[98] An elevated building on one side of the courtyard held the Bastille's archives.[99] A clock was installed by Antoine de Sartine, the lieutenant general of police between 1759 and 1774, on the side of the office wing, depicting two chained prisoners.[100]

New kitchens and baths were built just outside the main gate to the Bastille in 1786.[90] The ditch around the Bastille, now largely dry, supported a 36-foot (11 m) high stone wall with a wooden walkway for the use of the guards, known as "la ronde", or the round.[101] An outer court had grown up around the south-west side of the Bastille, adjacent to the Arsenal. This was open to the public and lined with small shops rented out by the governor for almost 10,000 livres a year, complete with a lodge for the Bastille gatekeeper; it was illuminated at night to light the adjacent street.[102]

The Bastille was run by the governor, sometimes called the captain-governor, who lived in a 17th-century house alongside the fortress.[103] The governor was supported by various officers, in particular his deputy, the lieutenant de roi, or lieutenant of the king, who was responsible for general security and the protection of state secrets; the major, responsible for managing the Bastille's financial affairs and the police archives; and the capitaine des portes, who ran the entrance to the Bastille.[103] Four warders divided up the eight towers between them.[104] From an administrative perspective, the prison was generally well run during the period.[103] These staff were supported by an official surgeon, a chaplain and could, on occasion, call upon the services of a local midwife to assist pregnant prisoners.[105][H] A small garrison of "invalides" was appointed in 1749 to guard the interior and exterior of the fortress; these were retired soldiers and were regarded locally, as Simon Schama describes, as "amiable layabouts" rather than professional soldiers.[107]

Use of the prison

Jansenist convulsionnaires exercising in the outer court

The role of the Bastille as a prison changed considerably during the reigns of Louis XV and XVI. One trend was a decline in the number of prisoners sent to the Bastille, with 1,194 imprisoned there during the reign of Louis XV and only 306 under Louis XVI up until the Revolution, annual averages of around 23 and 20 respectively.[65][I] A second trend was a slow shift away from the Bastille's 17th-century role of detaining primarily upper-class prisoners, towards a situation in which the Bastille was essentially a location for imprisoning socially undesirable individuals of all backgrounds – including aristocrats breaking social conventions, criminals, pornographers, thugs – and was used to support police operations, particularly those involving censorship, across Paris.[108] Despite these changes, the Bastille remained a state prison, subject to special authorities, answering to the monarch of the day and surrounded by a considerable and threatening reputation.[109]

Under Louis XV, around 250 Catholic convulsionnaires, often called Jansenists, were detained in the Bastille for their religious beliefs.[110] Many of these prisoners were women and came from a wider range of social backgrounds than the upper-class Calvinists detained under Louis XIV; historian Monique Cottret argues that the decline of the Bastille's social "mystique" originates from this phase of detentions.[111] By Louis XVI, the background of those entering the Bastille and the type of offences they were detained over had changed markedly. Between 1774 and 1789, the detentions included 54 people accused of robbery; 31 of involvement in the 1775 Famine Revolt; 11 detained for assault; 62 illegal editors, printers and writers – but relatively few detained over the grander affairs of state.[74]

Many prisoners still continued to come from the upper classes, particularly in those cases termed "désordres des familles", or disorders of the family. These cases typically involving members of the aristocracy who had, as historian Richard Andrews notes, "rejected parental authority, disgraced the family reputation, manifested mental derangement, squandered capital or violated professional codes."[112] Their families – often their parents, but sometimes husbands and wives taking action against their spouses – could apply for individuals to be detained at one of the royal prisons, resulting in an average imprisonment of between six months and four years.[113] Such a detention could be preferable to facing a scandal or a public trial over their misdemeanours, and the secrecy that surrounded detention at the Bastille allowed personal and family reputations to be quietly protected.[114] The Bastille was considered one of the best prisons for an upper-class prisoner to be detained at, because of the standard of the facilities for the wealthy.[115] In the aftermath of the notorious "Affair of the Diamond Necklace" of 1786, involving the Queen and accusations of fraud, all the eleven suspects were held in the Bastille, significantly increasing the notoriety surrounding the institution.[116]

The Bastille and the Porte Saint-Antoine, seen from the east

Increasingly, however, the Bastille became part of the system of wider policing in Paris. Although appointed by the king, the governor reported to the lieutenant general of police: the first of these, Gabriel Nicolas de la Reynie, made only occasional visits to the Bastille, but his successor, Marquis d'Argenson, and subsequent officers used the facility extensively and took a close interest in inspections of the prison.[117] The lieutenant general reported in turn to the secretary of the "Maison du Roi", largely responsible for order in the capital; in practice together they controlled the issuing of the "lettres" in the king's name.[118] The Bastille was unusual among Parisian prisons in that it acted on behalf of the king – prisoners could therefore be imprisoned secretly, for longer, and without normal judicial processes being applied, making it a useful facility for the police authorities.[119] The Bastille was a preferred location for holding prisoners who needed extensive questioning or where a case required the analysis of extensive documents.[120] The Bastille was also used to store the Parisian police archives; public order equipment such as chains and flags; and illegal goods, seized by order of the crown using a version of the "lettre de cachet", such as banned books and illicit printing presses.[121]

Throughout this period, but particularly in the middle of the 18th century, the Bastille was used by the police to suppress the trade in illegal and seditious books in France.[122] In the 1750s, 40% of those sent to the Bastille were arrested for their role in manufacturing or dealing in banned material; in the 1760s, the equivalent figure was 35%.[122][J] Seditious writers were also often held in the Bastille, although many of the more famous writers held in the Bastille during the period were formally imprisoned for more anti-social, rather than strictly political, offences.[124] In particular, many of those writers detained under Louis XVI were imprisoned for their role in producing illegal pornography, rather than political critiques of the regime.[74] The writer Laurent Angliviel de la Beaumelle, the philosopher André Morellet and the historian Jean-François Marmontel, for example, were formally detained not for their more obviously political writings, but for libellous remarks or for personal insults against leading members of Parisian society.[125]

Prison regime

A sketch of the main courtyard in 1785[K]

Contrary to its later image, conditions for prisoners in the Bastille by the mid-18th century were in fact relatively benign, particularly by the standards of other prisons of the time.[127] The typical prisoner was held in one of the octagonal rooms in the mid-levels of the towers.[128] The calottes, the rooms just under the roof that formed the upper storey of the Bastille, were considered the least pleasant quarters, being more exposed to the elements and usually either too hot or too cold.[129] The cachots, the underground dungeons, had not been used for many years except for holding recaptured escapees.[129] Prisoners' rooms each had a stove or a fireplace, basic furniture, curtains and in most cases a window. A typical criticism of the rooms was that they were shabby and basic rather than uncomfortable.[130][L] Like the calottes, the main courtyard, used for exercise, was often criticised by prisoners as being unpleasant at the height of summer or winter, although the garden in the bastion and the castle walls were also used for recreation.[132]

The governor received money from the Crown to support the prisoners, with the amount varying on rank: the governor received 19 livres a day for each political prisoner – with conseiller-grade nobles receiving 15 livres – and, at the other end of the scale, three livres a day for each commoner.[133] Even for the commoners, this sum was around twice the daily wage of a labourer and provided for an adequate diet, while the upper classes ate very well: even critics of the Bastille recounted many excellent meals, often taken with the governor himself.[134][M] Prisoners who were being punished for misbehaviour, however, could have their diet restricted as a punishment.[136] The medical treatment provided by the Bastille for prisoners was excellent by the standards of the 18th century; the prison also contained a number of inmates suffering from mental illnesses and took, by the standards of the day, a very progressive attitude to their care.[137]

The council chamber, sketched in 1785

Although potentially dangerous objects and money were confiscated and stored when a prisoner first entered the Bastille, most wealthy prisoners continued to bring in additional luxuries, including pet dogs or cats to control the local vermin.[138] The Marquis de Sade, for example, arrived with an elaborate wardrobe, paintings, tapestries, a selection of perfume, and a collection of 133 books.[133] Card games and billiards were played among the prisoners, and alcohol and tobacco were permitted.[139] Servants could sometimes accompany their masters into the Bastille, as in the cases of the 1746 detention of the family of Lord Morton and their entire household as British spies: the family's domestic life continued on inside the prison relatively normally.[140] The prisoners' library had grown during the 18th century, mainly through ad hoc purchases and various confiscations by the Crown, until by 1787 it included 389 volumes.[141]

The length of time that a typical prisoner was kept at the Bastille continued to decline, and by Louis XVI's reign the average length of detention was only two months.[74] Prisoners would still be expected to sign a document on their release, promising not to talk about the Bastille or their time within it, but by the 1780s this agreement was frequently broken.[103] Prisoners leaving the Bastille could be granted pensions on their release by the Crown, either as a form of compensation or as a way of ensuring future good behaviour – Voltaire was granted 1,200 livres a year, for example, while Latude received an annual pension of 400 livres.[142][N]

Criticism and reform

Dragons destroy the Bastille on the title page of Bucquoy's Die Bastille oder die Hölle der Lebenden.

During the 18th century, the Bastille was extensively critiqued by French writers as a symbol of ministerial despotism; this criticism would ultimately result in reforms and plans for its abolition.[144] The first major criticism emerged from Constantin de Renneville, who had been imprisoned in the Bastille for 11 years and published his accounts of the experience in 1715 in his book L'Inquisition françois.[145] Renneville presented a dramatic account of his detention, explaining that despite being innocent he had been abused and left to rot in one of the Bastille's cachot dungeons, kept enchained next to a corpse.[146] More criticism followed in 1719 when the Abbé Jean de Bucquoy, who had escaped from the Bastille ten years previously, published an account of his adventures from the safety of Hanover; he gave a similar account to Renneville's and termed the Bastille the "hell of the living".[147] Voltaire added to the notorious reputation of the Bastille when he wrote about the case of the "Man in the Iron Mask" in 1751, and later criticised the way he himself was treated while detained in the Bastille, labelling the fortress a "palace of revenge".[148][O]

In the 1780s, prison reform became a popular topic for French writers and the Bastille was increasingly critiqued as a symbol of arbitrary despotism.[150] Two authors were particularly influential during this period. The first was Simon-Nicholas Linguet, who was arrested and detained at the Bastille in 1780, after publishing a critique of Maréchal Duras.[151] Upon his release, he published his Mémoires sur la Bastille in 1783, a damning critique of the institution.[152] Linguet criticised the physical conditions in which he was kept, sometimes inaccurately, but went further in capturing in detail the more psychological effects of the prison regime upon the inmate.[153][P] Linguet also encouraged Louis XVI to destroy the Bastille, publishing an engraving depicting the king announcing to the prisoners "may you be free and live!", a phrase borrowed from Voltaire.[144]

Linguet's work was followed by another prominent autobiography, Henri Latude's Le despotisme dévoilé.[154] Latude was a soldier who was imprisoned in the Bastille following a sequence of complex misadventures, including the sending of a letter bomb to Madame de Pompadour, the King's mistress.[154] Latude became famous for managing to escape from the Bastille by means of climbing up the chimney of his cell and then descending the walls with a home-made rope ladder, before being recaptured afterwards in Amsterdam by French agents.[155] Latude was released in 1777, but was rearrested following his publication of a book entitled Memoirs of Vengeance.[156] Pamphlets and magazines publicised Latude's case until he was finally released again in 1784.[157] Latude became a popular figure with the "Académie française", or French Academy, and his autobiography, although inaccurate in places, did much to reinforce the public perception of the Bastille as a despotic institution.[158][Q]

Linguet's Mémoires sur la Bastille, depicting the fictional destruction of the Bastille by Louis XVI

Modern historians of this period, such as Hans-Jürgen Lüsebrink, Simon Schama and Monique Cottret, concur that the actual treatment of prisoners in Bastille was much better than the public impression left through these writings.[160] Nonetheless, fuelled by the secrecy that still surrounded the Bastille, official as well as public concern about the prison and the system that supported it also began to mount, prompting reforms.[161] As early as 1775, Louis XVI's minister Malesherbes had authorised all prisoners to be given newspapers to read, and to be allowed to write and to correspond with their family and friends.[162] In the 1780s Breteuil, the Secretary of State of the Maison du Roi, began a substantial reform of the system of lettres de cachet that sent prisoners to the Bastille: such letters were now required to list the length of time a prisoner would be detained for, and the offence for which they were being held.[163]

Meanwhile, in 1784, the architect Alexandre Brogniard proposed that the Bastille be demolished and converted into a circular, public space with colonnades.[157] Director-General of Finance Jacques Necker, having examined the costs of running the Bastille, amounting to well over 127,000 livres in 1774, for example, proposed closing the institution on the grounds of economy alone.[164][R] Similarly, Puget, the Bastille's lieutenant de roi, submitted reports in 1788 suggesting that the authorities close the prison, demolish the fortress and sell the real estate off.[165] In June 1789, the Académie royale d'architecture proposed a similar scheme to Brogniard's, in which the Bastille would be transformed into an open public area, with a tall column at the centre surrounded by fountains, dedicated to Louis XVI as the "restorer of public freedom".[157] The number of prisoners held in the Bastille at any one time declined sharply towards the end of Louis's reign; the prison contained ten prisoners in September 1782 and, despite a mild increase at the beginning of 1788, by July 1789 only seven prisoners remained in custody.[166] Before any official scheme to close the prison could be enacted, however, disturbances across Paris brought a more violent end to the Bastille.[157]

The French Revolution

Storming of the Bastille

An eye witness painting of the siege of the Bastille by Claude Cholat[S]

By July 1789, revolutionary sentiment was rising in Paris. The Estates-General was convened in May and members of the Third Estate proclaimed the Tennis Court Oath in June, calling for the king to grant a written constitution. Violence between loyal royal forces, mutinous members of the royal Gardes Françaises and local crowds broke out at Vendôme on 12 July, leading to widespread fighting and the withdrawal of royal forces from the centre of Paris.[168] Revolutionary crowds began to arm themselves during 13 July, looting royal stores, gunsmiths and armourers' shops for weapons and gunpowder.[168]

The commander of the Bastille at the time was Bernard-René de Launay, a conscientious but minor military officer.[169] Tensions surrounding the Bastille had been rising for several weeks. Only seven prisoners remained in the fortress, - the Marquis de Sade had been transferred to the asylum of Charenton, after addressing the public from his walks on top of the towers and, once this was forbidden, shouting from the window of his cell.[170] Sade had claimed that the authorities planned to massacre the prisoners in the castle, which resulted in the governor removing him to an alternative site in early July.[169]

At de Launay's request, an additional force of 32 soldiers from the Swiss Salis-Samade regiment had been assigned to the Bastille on 7 July, adding to the existing 82 invalides pensioners who formed the regular garrison.[169] De Launay had taken various precautions, raising the drawbridge in the Comté tower and destroying the stone abutment that linked the Bastille to its bastion to prevent anyone from gaining access from that side of the fortress.[171] The shops in the entranceway to the Bastille had been closed and the gates locked. The Bastille was defended by 30 small artillery pieces, but nonetheless, by 14 July de Launay was very concerned about the Bastille's situation.[169] The Bastille, already hugely unpopular with the revolutionary crowds, was now the only remaining royalist stronghold in central Paris, in addition to which he was protecting a recently arrived stock of 250 barrels of valuable gunpowder.[169] To make matters worse, the Bastille had only two days' supply of food and no source of water, making it impossible to withstand a long siege.[169][T]

A plan of the Bastille and surrounding buildings made immediately after 1789; the red dot marks the perspective of Claude Cholat's painting of the siege.

On the morning of 14 July around 900 people formed outside the Bastille, primarily working-class members of the nearby faubourg Saint-Antoine, but also including some mutinous soldiers and local traders.[172] The crowd had gathered in an attempt to commandeer the gunpowder stocks known to be held in the Bastille, and at 10:00 am de Launay let in two of their leaders to negotiate with him.[173] Just after midday, another negotiator was let in to discuss the situation, but no compromise could be reached: the revolutionary representatives now wanted both the guns and the gunpowder in the Bastille to be handed over, but de Launay refused to do so unless he received authorisation from his leadership in Versailles.[174] By this point it was clear that the governor lacked the experience or the skills to defuse the situation.[175]

Just as negotiations were about to recommence at around 1:30 pm, chaos broke out as the impatient and angry crowd stormed the outer courtyard of the Bastille, pushing toward the main gate.[176] Confused firing broke out in the confined space and chaotic fighting began in earnest between de Launay's forces and the revolutionary crowd as the two sides exchanged fire.[177] At around 3:30 pm, more mutinous royal forces arrived to reinforce the crowd, bringing with them trained infantry officers and several cannons.[178] After discovering that their weapons were too light to damage the main walls of the fortress, the revolutionary crowd began to fire their cannons at the wooden gate of the Bastille.[179] By now around 83 of the crowd had been killed and another 15 mortally wounded; only one of the Invalides had been killed in return.[180]

De Launay had limited options: if he allowed the Revolutionaries to destroy his main gate, he would have to turn the cannon directly inside the Bastille's courtyard on the crowds, causing great loss of life and preventing any peaceful resolution of the episode.[179] De Launay could not withstand a long siege, and he was dissuaded by his officers from committing mass suicide by detonating his supplies of powder.[181] Instead, de Launay attempted to negotiate a surrender, threatening to blow up the Bastille if his demands were not met.[180] In the midst of this attempt, the Bastille's drawbridge suddenly came down and the revolutionary crowd stormed in. Popular myth believes Stanislas Marie Maillard was the first revolutionary to enter to the fortress.[182] De Launay was dragged outside into the streets and killed by the crowd, and three officers and three soldiers were killed during the course of the afternoon by the crowd.[183] The soldiers of the Swiss Salis-Samade Regiment, however, were not wearing their uniform coats and were mistaken for Bastille prisoners; they were left unharmed by the crowds until they were escorted away by French Guards and other regular soldiers among the attackers.[184] The valuable powder and guns were seized and a search begun for the other prisoners in the Bastille.[180]

Destruction

The demolition of the walls of the Bastille, July 1789

Within hours of its capture, the Bastille began to be used as a powerful symbol to give legitimacy to the revolutionary movement in France.[185] The faubourg Saint-Antoine's revolutionary reputation was firmly established by their storming of the Bastille and a formal list began to be drawn up of the "vainqueurs" who had taken part so as to honor both the fallen and the survivors.[186] Although the crowd had initially gone to the Bastille searching for gunpowder, historian Simon Schama observes how the captured prison "gave a shape and an image to all the vices against which the Revolution defined itself".[187] Indeed, the more despotic and evil the Bastille was portrayed by the pro-revolutionary press, the more necessary and justified the actions of the Revolution became.[187] Consequently, the late governor, de Launay, was rapidly vilified as a brutal despot.[188] The fortress itself was described by the revolutionary press as a "place of slavery and horror", containing "machines of death", "grim underground dungeons" and "disgusting caves" where prisoners were left to rot for up to 50 years.[189]

As a result, in the days after 14 July, the fortress was searched for evidence of torture: old pieces of armour and bits of a printing press were taken out and presented as evidence of elaborate torture equipment.[190] Latude returned to the Bastille, where he was given the rope ladder and equipment with which he had escaped from the prison many years before.[190] The former prison warders escorted visitors around the Bastille in the weeks after its capture, giving colourful accounts of the events in the castle.[191] Stories and pictures about the rescue of the fictional Count de Lorges – supposedly a mistreated prisoner of the Bastille incarcerated by Louis XV – and the similarly imaginary discovery of the skeleton of the "Man in the Iron Mask" in the dungeons, were widely circulated as fact across Paris.[192] In the coming months, over 150 broadside publications used the storming of the Bastille as a theme, while the events formed the basis for a number of theatrical plays.[193]

Despite a thorough search, the revolutionaries discovered only seven prisoners in the Bastille, rather fewer than had been anticipated.[194] Of these, only one – de Whyte de Malleville, an elderly and white-bearded man – closely resembled the public image of a Bastille prisoner; despite being mentally ill, he was paraded through the streets, where he waved happily to the crowds.[190] Of the remaining six liberated prisoners, four were convicted forgers who quickly vanished into the Paris streets; one was the Count de Solages, who had been imprisoned on the request of his family for sexual misdemeanours; the sixth was a man called Tavernier, who also proved to be mentally ill and, along with Whyte, was in due course reincarcerated in the Charenton asylum.[195][U]

A model of the Bastille made by Pierre-François Palloy from one of the stones of the fortress

At first the revolutionary movement was uncertain whether to destroy the prison, to reoccupy it as a fortress with members of the volunteer guard militia, or to preserve it intact as a permanent revolutionary monument.[196] The revolutionary leader Mirabeau eventually settled the matter by symbolically starting the destruction of the battlements himself, after which a panel of five experts was appointed by the Permanent Committee of the Hôtel de Ville to manage the demolition of the castle.[191][V] One of these experts was Pierre-François Palloy, a bourgeois entrepreneur who claimed vainqueur status for his role during the taking of the Bastille, and he rapidly assumed control over the entire process.[198] Palloy's team worked quickly and by November most of the fortress had been destroyed.[199]

The ruins of the Bastille rapidly became iconic across France.[190] Palloy had an altar set up on the site in February 1790, formed out of iron chains and restraints from the prison.[199] Old bones, probably of 15th century soldiers, were discovered during the clearance work in April and, presented as the skeletons of former prisoners, were exhumed and ceremonially reburied in Saint-Paul's cemetery.[200] In the summer, a huge ball was held by Palloy on the site for the National Guardsmen visiting Paris for the 14 July celebrations.[200] A memorabilia industry surrounding the fall of the Bastille was already flourishing and as the work on the demolition project finally dried up, Palloy started producing and selling memorabilia of the Bastille.[201][W] Palloy's products, which he called "relics of freedom", celebrated the national unity that the events of July 1789 had generated across all classes of French citizenry, and included a very wide range of items.[203][X] Palloy also sent models of the Bastille, carved from the fortress's stones, as gifts to the French provinces at his own expense to spread the revolutionary message.[204] In 1793 a large revolutionary fountain featuring a statue of Isis was built on the former site of the fortress, which became known as the Place de la Bastille.[205]

19th–20th century political and cultural legacy

The foundations of the Liberté Tower of the Bastille, rediscovered during excavations for the Métro in 1899[206]

The Bastille remained a powerful and evocative symbol for French republicans throughout the 19th century.[207]Napoleon Bonaparte overthrew the French First Republic that emerged from the Revolution in 1799, and subsequently attempted to marginalise the Bastille as a symbol.[208] Napoleon was unhappy with the revolutionary connotations of the Place de la Bastille, and initially considered building his Arc de Triomphe on the site instead.[209] This proved an unpopular option and so instead he planned the construction of a huge, bronze statue of an imperial elephant.[209] The project was delayed, eventually indefinitely, and all that was constructed was a large plaster version of the bronze statue, which stood on the former site of the Bastille between 1814 and 1846, when the decaying structure was finally removed.[209] After the restoration of the French Bourbon monarchy in 1815, the Bastille became an underground symbol for Republicans.[208] The July Revolution in 1830, used images such as the Bastille to legitimise their new regime and in 1833, the former site of the Bastille was used to build the July Column to commemorate the revolution.[210] The short-lived Second Republic was symbolically declared in 1848 on the former revolutionary site.[211]

The storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789, had been celebrated annually since 1790, initially through quasi-religious rituals, and then later during the Revolution with grand, secular events including the burning of replica Bastilles.[212] Under Napoleon the events became less revolutionary, focusing instead on military parades and national unity in the face of foreign threats.[213] During the 1870s, the 14 July celebrations became a rallying point for Republicans opposed to the early monarchist leadership of the Third Republic; when the moderate Republican Jules Grévy became president in 1879, his new government turned the anniversary of the fall of the Bastille into a national holiday.[214] The anniversary remained contentious, with hard-line Republicans continuing to use the occasion to protest against the new political order and right-wing conservatives protesting about the imposition of the holiday.[215] The July Column itself remained contentious and Republican radicals unsuccessfully tried to blow it up in 1871.[216]

Meanwhile, the legacy of the Bastille proved popular among French novelists. Alexandre Dumas, for example, used the Bastille and the legend of the "Man in the Iron Mask" extensively in his d'Artagnan Romances; in these novels the Bastille is presented as both picturesque and tragic, a suitable setting for heroic action.[217] By contrast, in many of Dumas's other works, such as Ange Pitou, the Bastille takes on a much darker appearance, being described as a place in which a prisoner is "forgotten, bankrupted, buried, destroyed".[218] In England, Charles Dickens took a similar perspective when he drew on popular histories of the Bastille in writing A Tale of Two Cities, in which Doctor Manette is "buried alive" in the prison for 18 years; many historical figures associated with the Bastille are reinvented as fictional individuals in the novel, such as Claude Cholat, reproduced by Dickens as "Ernest Defarge".[219]Victor Hugo's 1862 novel Les Miserables, set just after the Revolution, gave Napoleon's plaster Bastille elephant a permanent place in literary history. In 1889 the continued popularity of the Bastille with the public was illustrated by the decision to build a replica in stone and wood for the Exposition Universelle world fair in Paris, manned by actors in period costumes.[220]

Due in part to the diffusion of national and Republican ideas across France during the second half of the Third Republic, the Bastille lost an element of its prominence as a symbol by the 20th century.[221] Nonetheless, the Place de la Bastille continued to be the traditional location for left wing rallies, particularly in the 1930s, the symbol of the Bastille was widely evoked by the French Resistance during the Second World War and until the 1950s Bastille Day remained the single most significant French national holiday.[222]

Remains

Remaining stones of the Bastille are still visible now on Boulevard Henri IV.

Due to its destruction after 1789, very little remains of the Bastille in the 21st century.[103] During the excavations for the Métro underground train system in 1899, the foundations of the Liberté Tower were uncovered and moved to the corner of the Boulevard Henri IV and the Quai de Celestins, where they can still be seen today.[223] The Pont de la Concorde contains stones reused from the Bastille.[224]

Some relics of the Bastille survive: the Carnavalet Museum holds objects including one of the stone models of the Bastille made by Palloy and the rope ladder used by Latude to escape from the prison roof in the 18th century, while the mechanism and bells of the prison clock are exhibited in Musée Européen d'Art Campanaire at L'Isle-Jourdain.[225] The key to the Bastille was given to George Washington in 1790 by Lafayette and is displayed in the historic house of Mount Vernon.[226] The Bastille's archives are now held by the Bibliothèque nationale de France.[227]

The Place de la Bastille still occupies most of the location of the Bastille, and the Opéra Bastille was built on the square in 1989 to commemorate the bicentennial anniversary of the storming of the prison.[216] The surrounding area has largely been redeveloped from its 19th-century industrial past. The ditch that originally linked the defences of the fortress to the River Seine had been dug out at the start of the 19th century to form the industrial harbour of the Bassin de l'Arsenal, linked to the Canal Saint Martin, but is now a marina for pleasure boats, while the Promenade Plantée links the square with redeveloped parklands to the east.[228]

Historiography

Journal of Antoine-Jérôme de Losme, the Bastille major, describing the days before the fall of the Bastille in 1789

A number of histories of the Bastille were published immediately after July 1789, usually with dramatic titles promising the uncovering of secrets from the prison.[229] By the 1830s and 1840s, popular histories written by Pierre Joigneaux and by the trio of Auguste Maquet, Auguste Arnould and Jules-Édouard Alboize de Pujol presented the years of the Bastille between 1358 and 1789 as a single, long period of royal tyranny and oppression, epitomised by the fortress; their works featured imaginative 19th-century reconstructions of the medieval torture of prisoners.[230] As living memories of the Revolution faded, the destruction of the Bastille meant that later historians had to rely primarily on memoires and documentary materials in analysing the fortress and the 5,279 prisoners who had come through the Bastille between 1659 and 1789.[231] The Bastille's archives, recording the operation of the prison, had been scattered in the confusion after the seizure; with some effort, the Paris Assembly gathered around 600,000 of them in the following weeks, which form the basis of the modern archive.[232] After being safely stored and ignored for many years, these archives were rediscovered by the French historian François Ravaisson, who catalogued and used them for research between 1866 and 1904.[233]

At the end of the 19th century the historian Frantz Funck-Brentano used the archives to undertake detailed research into the operation of the Bastille, focusing on the upper class prisoners in the Bastille, disproving many of the 18th-century myths about the institution and portraying the prison in a favourable light.[234] Modern historians today consider Funck-Brentano's work slightly biased by his anti-Republican views, but his histories of the Bastille were highly influential and were largely responsible for establishing that the Bastille was a well-run, relatively benign institution.[235] Historian Fernand Bournon used the same archive material to produce the Histoire de la Bastille in 1893, considered by modern historians to be one of the best and most balanced 19th-century histories of the Bastille.[236] These works inspired the writing of a sequence of more popular histories of the Bastille in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including Auguste Coeuret's anniversary history of the Bastille, which typically focused on a handful of themes and stories involving the more glamorous prisoners from the upper classes of French society.[237]

One of the major debates on the actual taking of the Bastille in 1789 has been the nature of the crowds that stormed the building. Hippolyte Taine argued in the late 19th century that the crowd consisted of unemployed vagrants, who acted without real thought; by contrast, the post-war left-wing intellectual George Rudé argued that the crowd was dominated by relatively prosperous artisan workers.[238] The matter was reexamined by Jacques Godechot in the post-war years; Godechot showing convincingly that, in addition to some local artisans and traders, at least half the crowd that gathered that day were, like the inhabitants of the surrounding faubourg, recent immigrants to Paris from the provinces.[239] Godechot used this to characterise the taking of the Bastille as a genuinely national event of wider importance to French society.[240]

In the 1970s French sociologists, particularly those interested in critical theory, re-examined this historical legacy.[229] The Annales School conducted extensive research into how order was maintained in pre-revolutionary France, focusing on the operation of the police, concepts of deviancy and religion.[229] Histories of the Bastille since then have focused on the prison's role in policing, censorship and popular culture, in particular how these impacted on the working classes.[229] Research in West Germany during the 1980s examined the cultural interpretation of the Bastille against the wider context of the French Revolution; Hanse Lüsebrink and Rolf Reichardt's work, explaining how the Bastille came to be regarded as a symbol of despotism, was among the most prominent.[241] This body of work influenced historian Simon Schama's 1989 book on the Revolution, which incorporated cultural interpretation of the Bastille with a controversial critique of the violence surrounding the storming of the Bastille.[242] The Bibliothèque nationale de France held a major exhibition on the legacy of the Bastille between 2010 and 2011, resulting in a substantial edited volume summarising the current academic perspectives on the fortress.[243]

See also

- List of castles in France

Notes

Footnotes

^ An alternative opinion, held by Fernand Bournon, is that the first bastille was a completely different construction, possibly made just of earth, and that all of the later bastille was built under Charles V and his son.[4]

^ The Bastille can be seen in the background of Jean Fouquet's 15th-century depiction of Charles V's entrance into Paris.

^ Hugues Aubriot was subsequently taken from the Bastille to the For-l'Évêque, where he was then executed on charges of heresy.[23]

^ Converting medieval financial figures to modern equivalents is notoriously challenging. For comparison, 1,200 livres was around 0.8% of the French Crown's annual income from royal taxes in 1460.[30]

^ In practice, Henry IV's nobles appointed lieuentants to actually run the fortress.[50]

^ Andrew Trout suggests that the castle's library was originally a gift from Louis XIV; Martine Lefévre notes early records of the books of dead prisoners being lent out by the staff as a possible origin for the library, or alternatively that the library originated as a gift from Vinache, a rich Neapolitan.[76]

^ Converting 17th century financial sums into modern equivalents is extremely challenging; for comparison, 232,818 livres was around 1,000 times the annual wages of a typical labourer of the period.[81]

^ The Bastille's surgeon was also responsible for shaving the prisoners, as inmates were not permitted sharp objects such as razors.[106]

^ Using slightly different accounting methods, Hans-Jürgen Lüsebrink suggests fractionally lower totals for prisoner numbers between 1660–1789.[74]

^ Jane McLeod suggests that the breaching of censorship rules by licensed printers was rarely dealt with by regular courts, being seen as an infraction against the Crown, and dealt with by royal officials.[123]

^ This picture, by Jean-Honoré Fragonard, shows a number of elegantly dressed women; it is uncertain on what occasion the drawing was made, or what they were doing in Bastille at the time.[126]

^ Prisoners described the standard issue furniture as including "a bed of green serge with curtains of the same; a straw mat and a mattress; a table or two, two pitchers, a candleholder and a tin goblet; two or three chairs, a fork, a spoon and everything need to light a fire; by special favour, weak little tongs and two large stones for an andiron." Linguet complained of only initially having "two mattresses half eaten by the worms, a matted elbow chair... a tottering table, a water pitcher, two pots of Dutch ware and two flagstones to support the fire".[131]

^ Linguet noted that "there are tables less lacking; I confess it; mine was among them." Morellet reported that each day he received "a bottle of decent wine, an excellent one-pound loaf of bread; for dinner, a soup, some beef, an entrée and a desert; in the evening, some roast and a salad." The abbé Marmontel recorded dinners including "an excellent soup, a succulent slice of beef, a boiled leg of capon, dripping with fat and falling off the bone; a small plate of fried artichokes in a marinade, one of spinach, a very nice "cresonne" pear, fresh grapes, a bottle of old Burgundy wine, and the best Mocha coffee. At the other end of the scale, lesser prisoners might get only "a pound of bread and a bottle of bad wine a day; for dinner...broth and two meat dishes; for supper...a slice of roast, some stew, and some salad".[135]

^ Comparing 18th century sums of money with modern equivalents is notoriously difficult; for comparison, Latude's pension was around one and a third times that of a labourer's annual wage, while Voltaire's was very considerably more.[143]

^ Voltaire is usually considered to have exaggerated his hardships, as he received a string of visitors each day and in fact voluntarily stayed on within the Bastille after he was officially released in order to complete some business affairs. He also campaigned to have others sent to the Bastille.[149]

^ The accuracy of all of Linguet's records on the physical conditions have been questioned by modern historians, for example Simon Schama.[151]

^ Latude's inaccuracies include his referring to a new fur coat as "half-rotted rags", for example. Jacques Berchtold observes that Latude's writing also introduced the idea of the hero of the story actively resisting the despotic institution – in this case through escape – in contrast to earlier works which had portrayed the hero merely as the passive victim of oppression.[159]

^ Comparing 18th century sums of money with modern equivalents is notoriously difficult; for comparison, the Bastille's 127,000 livres running costs in 1774 were around 420 times a Parisian labourer's annual wages, or alternatively roughly half the cost of clothing and equipping the Queen in 1785.[143]

^ Claude Cholat was a wine merchant living in Paris on the rue Noyer at the start of 1789. Cholat fought on the side of the Revolutionaries during the storming of the Bastille, manning one of their cannon during the battle. Afterwards, Cholat produced a famous amateur gouache painting showing the events of the day; produced in primitive, naïve style, it combines all the events of the day into a single graphical representation.[167]

^ It is unclear why the Bastille's well was not functioning at this time.

^ Jacques-François-Xavier de Whyte, often called Major Whyte, had originally been imprisoned for sexual misdemeanours – by 1789 he believed himself to be Julius Caesar, accounting for his positive reaction to being paraded through the streets. Tavernier had been accused of attempting to assassinate Louis XV. The four forgers were later recaptured and imprisoned in the Bicêtre.[195]

^ Palloy actually began some limited demolition work on the evening of the 14 July, before any formal authorisation had been given.[197]

^ The extent to which Palloy was motivated by money, revolutionary zeal or both is unclear; Simon Schama is inclined to portray him as a businessman first, Hans-Jürgen Lüsebrink and Rolf Reichardt depict him as a slightly obsessed revolutionary.[202]

^ Palloy's products included a working model of the fortress; royal and revolutionary portraits; miscellaneous objects such as inkwells and paperweights, made from recycled parts of the Bastille; Latude's biography and other carefully selected items.[203]

Citations

^ ab Lansdale, p. 216.

^ Bournon, p. 1.

^ Viollet, p. 172; Coueret, p. 2; Lansdale, p. 216.

^ Bournon, p. 3.

^ Coueret, p. 2.

^ ab Viollet, p. 172; Landsdale, p. 218.

^ Viollet, p. 172; Landsdale, p. 218; Muzerelle (2010a), p. 14.

^ ab Coueret, p. 3, Bournon, p. 6.

^ Viollet, p. 172; Schama, p 331; Muzerelle (2010a), p. 14.

^ ab Anderson, p. 208.

^ Coueret, p. 52.

^ La Bastille ou « l’Enfer des vivants »?, Bibliothèque nationale de France, accessed 8 August 2011; Funck-Brentano, p. 62; Bournon, p. 48.

^ Viollet, p. 172.

^ Coueret, p. 36.

^ Lansdale, p. 221.

^ Toy, p. 215; Anderson, p. 208.

^ Anderson pp. 208, 283.

^ Anderson, pp. 208–09.

^ Lansdale, pp. 219–220.

^ Bournon, p. 7.

^ Lansdale, p .220; Bournon, p. 7.

^ abcd Coueret, p. 4.

^ Coueret, pp. 4, 46.

^ Bournon, pp. 7, 48.

^ Le Bas, p. 191.

^ Lansdale, p. 220.

^ La Bastille ou « l’Enfer des vivants »?, Bibliothèque nationale de France, accessed 8 August 2011; Lansdale, p. 220; Bournon, p. 49.

^ Coueret, p. 13; Bournon, p. 11.

^ Bournon, pp. 49, 51.

^ Curry, p. 82.

^ Funck-Brentano, p. 63.

^ Munck, p. 168.

^ Lansdale, p. 285.

^ Muzerelle (2010a), p. 14.

^ Funck-Bretano, p. 61; Muzerelle (2010a), p. 14.

^ Coueret, pp. 45, 57.

^ Coueret, p. 37.

^ Knecht, p. 449.

^ Knecht, pp. 451–2.

^ Knecht, p. 452.

^ Knecht, p. 459.

^ Freer, p. 358.

^ Freer, pp. 248, 356.

^ Freer, pp. 354–6.

^ Freer, pp. 356, 357–8.

^ Freer, pp. 364, 379.

^ Knecht, p. 486.

^ Funck-Brentano, p. 64; Lüsebrink and Reichardt, p. 6.

^ Funck-Brentano, p. 64; Bournon, p. 49.

^ Bournon, p. 49.

^ Funck-Brentano, p .65.

^ ab Munck, p. 212.

^ Sturdy, p. 27.

^ Lansdale, p. 324.

^ Munck, p. 212; Le Bas, p. 191.

^ Treasure, p. 141.

^ Treasure, p 141; Le Bas, p. 191.

^ Treasure, p. 171; Le Bas, p. 191.

^ Treasure, p. 198.

^ Sainte-Aulaire, p. 195; Hazan, p. 14.

^ Sainte-Aulaire, p. 195; Hazan, p. 14; Treasure, p. 198.

^ Trout, p. 12.

^ Coueret, p. 37; Hazan, pp. 14–5; La Bastille ou « l’Enfer des vivants »?, Bibliothèque nationale de France, accessed 8 August 2011.

^ Funck-Brentano, p. 61.

^ abcd La Bastille ou « l’Enfer des vivants »?, Bibliothèque nationale de France, accessed 8 August 2011.

^ Lüsebrink and Reichardt, p. 6.

^ Trout, pp. 140–1.

^ Collins, p. 103.

^ Cottret, p. 73; Trout, p. 142.

^ ab Trout, p. 142.

^ Trout, p. 143.

^ Trout, p. 141; Bély, pp. 124–5, citing Petitfils (2003).

^ ab Trout, p. 141.

^ abcde Lüsebrink, p. 51.

^ Lefévre, p. 156.

^ Trout, p. 141, Lefévre, p. 156.

^ Bournon, pp. 49, 52.

^ Dutray-Lecoin (2010b), p. 24; Collins, p. 149; McLeod, p. 5.

^ Bournon, p. 53.

^ Bournon, pp. 50–1.

^ Andrews, p. 66.

^ Funck-Brentano, pp. 72–3.

^ La Bastille ou « l’Enfer des vivants »?, Bibliothèque nationale de France, accessed 8 August 2011; Schama, p. 331.

^ ab Funck-Brentano, p. 73.

^ Garrioch, p. 22.

^ Garrioch, p. 22; Roche, p. 17.

^ Roche, p. 17.

^ Schama, p. 330.

^ Funck-Brentano, p. 58.

^ ab Chevallier, p. 148.

^ Coueret, pp .45–6.

^ ab Coueret, p. 46.

^ Coueret, p. 47; Funck-Brentano, pp. 59–60.

^ ab Coueret, p. 47.

^ Coueret, p. 47; Funck-Brentano, p. 60.

^ Coueret, p .48; Bournon, p. 27.

^ Coueret, p. 48.

^ Coueret, pp. 48–9.

^ Coueret, p. 49.

^ Reichardt, p. 226; Coueret, p. 51.

^ Coueret, p. 57; Funck-Brentano, p. 62.

^ Schama, p. 330; Coueret, p. 58; Bournon, pp. 25–6.

^ abcde Dutray-Lecoin (2010a), p. 136.

^ Bournon, p. 71.

^ Bournon, pp. 66, 68.

^ Linguet, p. 78.

^ Schama, p .339; Bournon, p. 73.

^ Denis, p. 38; Dutray-Lecoin (2010b), p. 24.

^ Dutray-Lecoin (2010b), p. 24.

^ Schama, p. 331; Lacam, p. 79.

^ Cottret, pp. 75–6.

^ Andrews, p. 270; Prade, p. 25.

^ Andrews, p. 270; Farge, p. 89.

^ Trout, pp. 141, 143.

^ Gillispie, p. 249.

^ Lüsebrink and Reichardt, pp. 25–6.

^ Funck-Brentano, p. 72; Dutray-Lecoin (2010a), p. 136.

^ Denis, p. 37; La Bastille ou « l’Enfer des vivants »?, Bibliothèque nationale de France, accessed 8 August 2011.

^ Denis, p .37.

^ Denis, pp. 38–9.

^ Funck-Brentano, p .81; La Bastille ou « l’Enfer des vivants »?, Bibliothèque nationale de France, accessed 8 August 2011.

^ ab Birn, p. 51.

^ McLeod, p. 6

^ Schama, p .331; Funck-Brentano, p. 148.

^ Funck-Brentano, pp. 156–9.

^ Dutray-Lecoin (2010c), p. 148.

^ Schama, pp. 331–2; Lüsebrink and Reichardt, pp. 29–32.

^ Schama, pp. 331–2.

^ ab Schama, p. 331.

^ Schama, p. 332; Linguet, p .69; Coeuret, p. 54-5.

^ Linguet, p. 69; Coeuret, p. 54-5, citing Charpentier (1789).

^ Bournon, p. 30.

^ ab Schama, p. 332.

^ Schama, p. 333; Andress, p.xiii; Chevallier, p. 151.

^ Chevallier, pp. 151–2, citing Morellet, p. 97, Marmontel, pp. 133–5 and Coueret, p. 20.

^ Funck-Brentano, p. 107; Chevallier, p. 152.

^ Lüsebrink and Reichardt, p. 31; Sérieux and Libert (1914), cited Lüsebrink and Reichardt, p. 31.

^ Schama, pp. 332, 335.

^ Schama, p. 333.

^ Farge, p. 153.

^ Lefévre, p. 157.

^ Funck-Brentano, p. 99.

^ ab Andress, p. xiii.

^ ab Reichardt, p. 226.

^ Lüsebrink and Reichardt, p. 10; Renneville (1719).

^ Lüsebrink and Reichardt, p. 11.

^ Coueret, p. 13; Lüsebrink and Reichardt, p. 12; Bucquoy (1719).

^ Lüsebrink and Reichardt, pp. 14–5, 26.

^ Lüsebrink and Reichardt, pp. 26–7.

^ Schama, p. 333; Lüsebrink and Reichardt, p. 19.

^ ab Schama, p. 334.

^ Schama, p. 334; Linguet (2005).

^ Schama, pp. 334–5.

^ ab Schama, p. 335.

^ Schama, pp. 336–7.

^ Schama, pp. 337–8.

^ abcd Schama, p. 338.

^ Schama, p. 338; Lüsebrink and Reichardt, p. 31; Latude (1790).

^ Lüsebrink and Reichardt, p. 31; Berchtold, pp. 143–5.

^ Schama, p. 334; Lüsebrink and Reichardt, p. 27.

^ Lüsebrink and Reichardt, p. 27.

^ Funck-Brentano, pp. 78–9.

^ Gillispie, p. 247; Funck-Brentano, p. 78.

^ Funck-Brentano, pp. 81–2.

^ Funck-Brentano, p. 83.

^ Funck-Brentano, p. 79.

^ Schama, p. 340-2, fig.6.

^ ab Schama, p. 327.

^ abcdef Schama, p. 339.

^ Schama, p. 339

^ Coueret, p. 57.

^ Schama, p. 340.

^ Schama, p. 340; Lüsebrink and Reichardt, p. 58.