Complications of diabetes mellitus

The lead section of this article may need to be rewritten. (July 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| Diabetes complication | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

The complications of diabetes mellitus are far less common and less severe in people who have well-controlled blood sugar levels. Acute complications include hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, diabetic coma and nonketotic hyperosmolar coma.

Chronic complications occur due to a mix of microangiopathy, macrovascular disease and immune dysfunction in the form of autoimmune disease or poor immune response, most of which are difficult to manage. Microangiopathy can affect all vital organs, kidneys, heart and brain, as well as eyes, nerves, lungs and locally gums and feet. Macrovascular problems can lead to cardiovascular disease including erectile dysfunction. Female infertility may be due to endocrine dysfunction with impaired signalling on a molecular level.

Other health problems compound the chronic complications of diabetes such as smoking, obesity, high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol levels, and lack of regular exercise which are accessible to management as they are modifiable. Non-modifiable risk factors of diabetic complications are type of diabetes, age of onset, and genetic factors, both protective and predisposing have been found.

Complications of diabetes mellitus are acute and chronic. Risk factors for them can be modifiable or not modifiable.

Overall, complications are far less common and less severe in people with well-controlled blood sugar levels.[1][2][3] However, (non-modifiable) risk factors such as age at diabetes onset, type of diabetes, gender and genetics play a role. Some genes appear to provide protection against diabetic complications, as seen in a subset of long-term diabetes type 1 survivors without complications.[4][5]

Contents

1 Statistics

2 Acute

2.1 Diabetic ketoacidosis

2.2 Hyperglycemia hyperosmolar state

2.3 Hypoglycemia

2.4 Diabetic coma

3 Chronic

3.1 Microangiopathy

3.2 Macrovascular disease

3.3 Abnormal immune responses

4 Risk factors

4.1 Age

4.2 Poor glucose control

4.3 Autoimmune processes

4.4 Genetic factors

4.5 Mechanisms

5 Management

5.1 Blood pressure control

5.2 Vitamins

6 References

7 External links

Statistics

As of 2010, there were about 675,000 diabetes-related emergency department (ED) visits in the U.S. which involved neurological complications, 409,000 ED visits with kidney complications, and 186,000 ED visits with eye complications.[6]

Acute

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is an acute and dangerous complication that is always a medical emergency and requires prompt medical attention. Low insulin levels cause the liver to turn fatty acid to ketone for fuel (i.e., ketosis); ketone bodies are intermediate substrates in that metabolic sequence. This is normal when periodic, but can become a serious problem if sustained. Elevated levels of ketone bodies in the blood decrease the blood's pH, leading to DKA. On presentation at hospital, the patient in DKA is typically dehydrated, and breathing rapidly and deeply. Abdominal pain is common and may be severe. The level of consciousness is typically normal until late in the process, when lethargy may progress to coma. Ketoacidosis can easily become severe enough to cause hypotension, shock, and death. Urine analysis will reveal significant levels of ketone bodies (which have exceeded their renal threshold blood levels to appear in the urine, often before other overt symptoms). Prompt, proper treatment usually results in full recovery, though death can result from inadequate or delayed treatment, or from complications (e.g., brain edema). Ketoacidosis is much more common in type 1 diabetes than type 2.

Hyperglycemia hyperosmolar state

Nonketotic hyperosmolar coma (HNS) is an acute complication sharing many symptoms with DKA, but an entirely different origin and different treatment. A person with very high (usually considered to be above 300 mg/dl (16 mmol/L)) blood glucose levels, water is osmotically drawn out of cells into the blood and the kidneys eventually begin to dump glucose into the urine. This results in loss of water and an increase in blood osmolarity. If fluid is not replaced (by mouth or intravenously), the osmotic effect of high glucose levels, combined with the loss of water, will eventually lead to dehydration. The body's cells become progressively dehydrated as water is taken from them and excreted. Electrolyte imbalances are also common and are always dangerous. As with DKA, urgent medical treatment is necessary, commonly beginning with fluid volume replacement. Lethargy may ultimately progress to a coma, though this is more common in type 2 diabetes than type 1.[citation needed]

Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia, or abnormally low blood glucose, is an acute complication of several diabetes treatments. It is rare otherwise, either in diabetic or non-diabetic patients. The patient may become agitated, sweaty, weak, and have many symptoms of sympathetic activation of the autonomic nervous system resulting in feelings akin to dread and immobilized panic. Consciousness can be altered or even lost in extreme cases, leading to coma, seizures, or even brain damage and death. In patients with diabetes, this may be caused by several factors, such as too much or incorrectly timed insulin, too much or incorrectly timed exercise (exercise decreases insulin requirements) or not enough food (specifically glucose containing carbohydrates). The variety of interactions makes cause identification difficult in many instances.

It is more accurate to note that iatrogenic hypoglycemia is typically the result of the interplay of absolute (or relative) insulin excess and compromised glucose counterregulation in type 1 and advanced type 2 diabetes. Decrements in insulin, increments in glucagon, and, absent the latter, increments in epinephrine are the primary glucose counterregulatory factors that normally prevent or (more or less rapidly) correct hypoglycemia. In insulin-deficient diabetes (exogenous) insulin levels do not decrease as glucose levels fall, and the combination of deficient glucagon and epinephrine responses causes defective glucose counterregulation.

Furthermore, reduced sympathoadrenal responses can cause hypoglycemia unawareness. The concept of hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure (HAAF) in diabetes posits that recent incidents of hypoglycemia causes both defective glucose counterregulation and hypoglycemia unawareness. By shifting glycemic thresholds for the sympathoadrenal (including epinephrine) and the resulting neurogenic responses to lower plasma glucose concentrations, antecedent hypoglycemia leads to a vicious cycle of recurrent hypoglycemia and further impairment of glucose counterregulation. In many cases (but not all), short-term avoidance of hypoglycemia reverses hypoglycemia unawareness in affected patients, although this is easier in theory than in clinical experience.

In most cases, hypoglycemia is treated with sugary drinks or food. In severe cases, an injection of glucagon (a hormone with effects largely opposite to those of insulin) or an intravenous infusion of dextrose is used for treatment, but usually only if the person is unconscious. In any given incident, glucagon will only work once as it uses stored liver glycogen as a glucose source; in the absence of such stores, glucagon is largely ineffective. In hospitals, intravenous dextrose is often used.

Diabetic coma

Diabetic coma is a medical emergency in which a person with diabetes mellitus is comatose (unconscious) because of one of the acute complications of diabetes:

- Severe diabetic hypoglycemia

Diabetic ketoacidosis advanced enough to result in unconsciousness from a combination of severe hyperglycemia, dehydration and shock, and exhaustion

Hyperosmolar nonketotic coma in which extreme hyperglycemia and dehydration alone are sufficient to cause unconsciousness.

Chronic

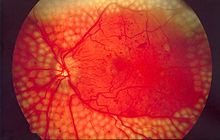

Image of fundus showing scatter laser surgery for diabetic retinopathy

Microangiopathy

The damage to small blood vessels leads to a microangiopathy, which can cause one or more of the following:

Diabetic nephropathy, damage to the kidney which can lead to chronic renal failure, eventually requiring renal dialysis. It is the most common cause of adult kidney failure in the developed world.[7]

Diabetic neuropathy, abnormal and decreased sensation, usually in a 'glove and stocking' distribution starting with the feet but potentially in other nerves, later often fingers and hands. When combined with damaged blood vessels this can lead to diabetic foot (see below). Other forms of diabetic neuropathy may present as mononeuritis or autonomic neuropathy. Diabetic amyotrophy is muscle weakness due to neuropathy.

Diabetic retinopathy, growth of friable and poor-quality new blood vessels in the retina as well as macular edema (swelling of the macula), which can lead to severe vision loss or blindness. Retinopathy is the most common cause of blindness among non-elderly adults in the developed world.[7]

Diabetic encephalopathy[8] is the increased cognitive decline and risk of dementia, including (but not limited to) the Alzheimer's type, observed in diabetes. Various mechanisms are proposed, like alterations to the vascular supply of the brain and the interaction of insulin with the brain itself.[9][10]

Diabetic cardiomyopathy, damage to the heart muscle, leading to impaired relaxation and filling of the heart with blood (diastolic dysfunction) and eventually heart failure; this condition can occur independent of damage done to the blood vessels over time from high levels of blood glucose.[11]

Erectile Dysfunction: Estimates of the prevalence of erectile dysfunction in men with diabetes range from 20 to 85 percent when defined as consistent inability to have an erection firm enough for sexual intercourse. Among men with erectile dysfunction, those with diabetes are likely to have experienced the problem as much as 10 to 15 years earlier than men without diabetes.[12]

Periodontal disease (gum disease) is associated with diabetes[13] which may make diabetes more difficult to treat.[14] A number of trials have found improved blood sugar levels in type 2 diabetics who have undergone periodontal treatment.[14]

Macrovascular disease

Macrovascular disease leads to cardiovascular disease, to which accelerated atherosclerosis is a contributor:

Coronary artery disease, leading to angina or myocardial infarction ("heart attack")

Diabetic myonecrosis ('muscle wasting')

Peripheral vascular disease, which contributes to intermittent claudication (exertion-related leg and foot pain) as well as diabetic foot.[15][7]

Stroke (mainly the ischemic type)

Carotid artery stenosis does not occur more often in diabetes, and there appears to be a lower prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm. However, diabetes does cause higher morbidity, mortality and operative risks with these conditions.[16]

- Diabetic foot, often due to a combination of sensory neuropathy (numbness or insensitivity) and vascular damage, increases rates of skin ulcers (diabetic foot ulcers) and infection and, in serious cases, necrosis and gangrene. It is why it takes longer for diabetics to heal from leg and foot wounds and why diabetics are prone to leg and foot infections. In the developed world is the most common cause of non-traumatic adult amputation, usually of toes and or feet.[15]

Female infertility is more common in women with diabetes type 1, despite modern treatment, also delayed puberty and menarche, menstrual irregularities (especially oligomenorrhoea), mild hyperandrogenism, polycystic ovarian syndrome, fewer live born children and possibly earlier menopause.[17] Animal models indicate that on the molecular level diabetes causes defective leptin, insulin and kisspeptin signalling.[17]

Abnormal immune responses

The immune response is impaired in individuals with diabetes mellitus. Cellular studies have shown that hyperglycemia both reduces the function of immune cells and increases inflammation.

Respiratory infections such as pneumonia and influenza are more common among individuals with diabetes. Lung function is altered by vascular disease and inflammation, which leads to an increase in susceptibility to respiratory agents. Several studies also show diabetes associated with a worse disease course and slower recovery from respiratory infections.[18]

Restrictive lung disease is known to be associated with diabetes. Lung restriction in diabetes could result from chronic low-grade tissue inflammation, microangiopathy, and/or accumulation of advanced glycation end products.[19] In fact the presence restrictive lung defect in association with diabetes has been shown even in presence of obstructive lung diseases like asthma and COPD in diabetic patients.[20]

Lipohypertrophy may be caused by insulin therapy. Repeated insulin injections at the same site, or near to, causes an accumulation of extra subcutaneous fat and may present as a large lump under the skin. It may be unsightly, mildly painful, and may change the timing or completeness of insulin action.- Depression was associated with diabetes in a 2010 longitudinal study of 4,263 individuals with type 2 diabetes, followed from 2005–2007. They were found to have a statistically significant association with depression and a high risk of micro and macro-vascular events.[21]

Risk factors

Age

Type 2 diabetes in youth brings a much higher prevalence of complications like diabetic kidney disease, retinopathy and peripheral neuropathy than type 1 diabetes, though no significant difference in the odds of arterial stiffness and hypertension.[22]

Poor glucose control

A 1988 study over 41 months found that improved glucose control led to initial worsening of complications but was not followed by the expected improvement in complications.[23] In 1993 it was discovered that the serum of diabetics with neuropathy is toxic to nerves, even if its blood sugar content is normal.[24]

Research from 1995 also challenged the theory of hyperglycemia as the cause of diabetic complications. The fact that 40% of diabetics who carefully controlled their blood sugar nevertheless developed neuropathy made clear other factors were involved.[25]

In a 2013 meta-analysis of 6 randomized controlled trials involving 27,654 patients, tight blood glucose control reduced the risk for some macrovascular and microvascular events but without effect on all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality.[26]

Autoimmune processes

Research from 2007 suggested that in type 1 diabetics, the continuing autoimmune disease which initially destroyed the beta cells of the pancreas may also cause retinopathy,[27][unreliable medical source?] neuropathy,[28] and nephropathy.[29]

In 2008 it was even suggested to treat retinopathy with drugs to suppress the abnormal immune response rather than by blood sugar control.[30]

Genetic factors

The known familial clustering of the type and degree of diabetic complications indicates, that genetics play a role in causing complications:

- the 2001 observation, that non-diabetic offspring of type 2 diabetics had increased arterial stiffness and neuropathy despite normal blood glucose levels,[31]

- the 2008 observation, that non-diabetic first-degree relatives of diabetics had elevated enzyme levels associated with diabetic renal disease[32] and nephropathy.[33]

- the 2007 finding that non-diabetic family members of type 1 diabetics had increased risk for microvascular complications,[34]

- such as diabetic retinopathy[35]

Mechanisms

Chronic elevation of blood glucose level leads to damage of blood vessels called angiopathy. The endothelial cells lining the blood vessels take in more glucose than normal, since they do not depend on insulin. They then form more surface glycoproteins than normal, and cause the basement membrane to grow thicker and weaker. The resulting problems are grouped under "microvascular disease" due to damage to small blood vessels and "macrovascular disease" due to damage to the arteries.[citation needed]

Studies show that DM1 and DM2 cause a change in balancing of metabolites such as carbohydrates, blood coagulation factors,[36] and lipids.[37] and subsequently bring about complications like microvascular and cardiovascular complications.

The role of metalloproteases and inhibitors in diabetic renal disease is unclear.[38]

Numerous researches have found inconsistent results about the role of vitamins in diabetic risk and complications.[39][clarification needed]

- Thiamine:

Thiamine acts as an essential cofactor in glucose metabolism,[40] therefore, it may modulate diabetic complications by controlling glycemic status in diabetic patients.[40][41] Additionally, deficiency of thiamine was observed to be associated with dysfunction of β-cells and impaired glucose tolerance.[41] Different studies indicated possible role of thiamin supplementation on the prevention or reversal of early stage diabetic nephropathy,[42][43] as well as significant improvement on lipid profile.[41]

- Vitamin B12:

Low serum B12 level is a common finding in diabetics especially those taking Metformin or in advanced age.[44] Vitamin B12 deficiency has been linked to two diabetic complications; atherosclerosis and diabetic neuropathy.[45][46]

- Folic acid:

Low plasma concentrations of folic acid were found to be associated with high plasma homocysteine concentrations.[47] In clinical trials, homocysteine concentrations were effectively reduced within 4 to 6 weeks of oral supplementation of folic acid.[48][49] Moreover, since the activity of endothelial NO synthase enzyme might be potentially elevated by folate,[50] folate supplementation might be capable of restoring the availability of NO in endothelium,[51] therefore, improving endothelial function and reducing the risk for atherosclerosis. van Etten et al., found that a single dose of folic acid might help in reducing the risk of vascular complications and enhancing endothelial function in adults with type 2 diabetes by improving nitric oxide status.[52]

- Antioxidants:

Three vitamins, ascorbic acid; α-tocopherol; and β-carotene, are well recognized for their antioxidant activities in human. Free radical-scavenging ability of antioxidants may reduce the oxidative stress and thus may protect against oxidative damage.[53] Based on observational studies among healthy individuals, antioxidant concentrations were found to be inversely correlated with several biomarkers of insulin resistance or glucose intolerance.[54][55]

Management

Blood pressure control

Modulating and ameliorating diabetic complications may improve the overall quality of life for diabetic patients. For example; when elevated blood pressure was tightly controlled, diabetic related deaths were reduced by 32% compared to those with less controlled blood pressure.[56]

Vitamins

Many observational and clinical studies have been conducted to investigate the role of vitamins on diabetic complications,[45]

In the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) Epidemiologic Follow-up Study, vitamin supplementations were associated with 24% reduction on the risk of diabetes[clarification needed], observed during 20 years of follow-up.[57]

Many observational studies and clinical trials have linked several vitamins with the pathological process of diabetes; these vitamins include folate,[48] thiamine,[42] β-carotene, and vitamin E,[54] C,[58] B12,[59] and D.[60]

- Vitamin D:

Vitamin D insufficiency is common in diabetics.[60] Observational studies show that serum vitamin D is inversely associated with biomarkers of diabetes; impaired insulin secretion, insulin resistance, and glucose intolerance.[61][62]

It has been suggested that vitamin D may induce beneficial effects on diabetic complications by modulating differentiation and growth of pancreatic β-cells and protecting these cells from apoptosis, thus improving β-cells functions and survival.[63] Vitamin D has also been suggested to act on immune system and modulate inflammatory responses by influencing proliferation and differentiation of different immune cells.[64][clarification needed], Moreover, deficiency of vitamin D may contribute to diabetic complications by inducing hyperparathyroidism, since elevated parathyroid hormone levels are associated with reduced β-cells function, impaired insulin sensitivity, and glucose intolerance.[60][61] Finally, vitamin D may reduce the risk of vascular complications by modulating lipid profile.[65]

Antioxidants may have beneficial effects on diabetic complications by reducing blood pressure, attenuating oxidative stress and inflammatory biomarkers, improving lipid metabolism, insulin-mediated glucose disposal, and by enhancing endothelial function.[54][66][67]

Vitamin C has been proposed to induce beneficial effects by two other mechanisms. It may replace glucose in many chemical reactions due to its similarity in structure, may prevent the non-enzymatic glycosylation of proteins,[59] and might reduce glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels.[55] Secondly, vitamin C has also been suggested to play a role in lipid regulation as a controlling catabolism of cholesterol to bile acid.[59]

References

^ Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, et al. (December 2005). "Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes". The New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (25): 2643–53. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052187. PMC 2637991. PMID 16371630..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "The effect of intensive diabetes therapy on the development and progression of neuropathy. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group". Annals of Internal Medicine. 122 (8): 561–68. April 1995. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-122-8-199504150-00001. PMID 7887548.

^ "Diabetes Complications". Diabetes.co.uk. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

^ Sun J; et al. (2011). "Protection from Retinopathy and Other Complications in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes of Extreme Duration". Diabetes Care. 34 (4): 968–974. doi:10.2337/dc10-1675. PMC 3064059. PMID 21447665.

^ Porta M; et al. (2016). "Variation in SLC19A3 and Protection from Microvascular Damage in Type 1 Diabetes". Diabetes. 65 (4): 1022–1030. doi:10.2337/db15-1247. PMC 4806664. PMID 26718501.

^ Washington R.E., Andrews R.M., Mutter R.L. Emergency Department Visits for Adults with Diabetes, 2010. HCUP Statistical Brief #167. November 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. [1].

^ abc Mailloux, Lionel (2007-02-13). "UpToDate Dialysis in diabetic nephropathy". UpToDate. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

^ Aristides Veves, Rayaz A. Malik (2007). Diabetic Neuropathy: Clinical Management (Clinical Diabetes), Second Edition. New York: Humana Press. pp. 188–98. ISBN 978-1-58829-626-9.

^ Gispen WH, Biessels GJ (November 2000). "Cognition and synaptic plasticity in diabetes mellitus". Trends in Neurosciences. 23 (11): 542–49. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01656-8. PMID 11074263.

^ "Diabetes doubles Alzheimer's risk". CNN. 2011-09-19.

^ Kobayashi S, Liang Q (May 2014). "Autophagy and mitophagy in diabetic cardiomyopathy". Biochim Biophys Acta. S0925-4439 (14): 148–43. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.05.020. PMID 24882754.

^ Dysfunction, Erectyle. "Erectile Dysfunction by Diabetes". doctor.ac. doctor.ac. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

^ Mealey, BL (October 2006). "Periodontal disease and diabetes. A two-way street". Journal of the American Dental Association. 137 Suppl: 26S–31S. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0404. PMID 17012733.

^ ab Lakschevitz, F; Aboodi, G; Tenenbaum, H; Glogauer, M (Nov 1, 2011). "Diabetes and periodontal diseases: interplay and links". Current Diabetes Reviews. 7 (6): 433–39. doi:10.2174/157339911797579205. PMID 22091748.

^ ab Scott, G (March–April 2013). "The diabetic foot examination: A positive step in the prevention of diabetic foot ulcers and amputation". Osteopathic Family Physician. 5 (2): 73–78. doi:10.1016/j.osfp.2012.08.002.

^ Weiss JS, Sumpio BE (February 2006). "Review of prevalence and outcome of vascular disease in patients with diabetes mellitus". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 31 (2): 143–50. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.08.015. PMID 16203161.

^ ab Codner, E.; Merino, P. M.; Tena-Sempere, M. (2012). "Female reproduction and type 1 diabetes: From mechanisms to clinical findings". Human Reproduction Update. 18 (5): 568–85. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms024. PMID 22709979.

^ Ahmed MS, Reid E, Khardori N (June 24, 2008). "Respiratory infections in diabetes: Reviewing the risks and challenges". Journal of Respiratory Diseases.

^ Connie C.W., Hsia (2008). "Lung Involvement in Diabetes Does it matter?". Diabetes Care. 31 (4): 828–829. doi:10.2337/dc08-0103. PMID 18375433. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

^ Mishra, G.P.; T.M. Dhamgaye; B.O. Tayade; et al. (December 2012). "Study of Pulmonary Function Tests in Diabetics with COPD or Asthma" (PDF). Applied Cardiopulmonary Pathophysiology. 16 (4–2012): 299–308. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

^ Lin, Elizabeth H. B.; Rutter, Carolyn M.; Katon, Wayne; Heckbert, Susan R.; Ciechanowski, Paul; Oliver, Malia M.; Ludman, Evette J.; Young, Bessie A.; Williams, Lisa H. (2010-02-01). "Depression and Advanced Complications of Diabetes A prospective cohort study". Diabetes Care. 33 (2): 264–69. doi:10.2337/dc09-1068. ISSN 0149-5992. PMC 2809260. PMID 19933989.

^ Dabelea D, Stafford JM, Mayer-Davis EJ, et al. (2017). "Association of type 1 diabetes vs type 2 diabetes diagnosed during childhood and adolescence with complications during teenage years and young adulthood". JAMA. 317 (8): 825–35. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.0686. PMC 5483855. PMID 28245334.

^ Brinchmann-Hansen O, Dahl-Jørgensen K, Hanssen KF, Sandvik L (September 1988). "The response of diabetic retinopathy to 41 months of multiple insulin injections, insulin pumps, and conventional insulin therapy". Arch. Ophthalmol. 106 (9): 1242–46. doi:10.1001/archopht.1988.01060140402041. PMID 3046587.

^ Pittenger GL, Liu D, Vinik AI (December 1993). "The toxic effects of serum from patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus on mouse neuroblastoma cells: a new mechanism for development of diabetic autonomic neuropathy". Diabet. Med. 10 (10): 925–32. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.1993.tb00008.x. PMID 8306588.

^ M. Centofani, "Diabetes Complications: More than Sugar?" Science News, vol. 149, no. 26/27, Dec. 23–30, p. 421 (1995)

^ Buehler, AM; Cavalcanti, AB; Berwanger, O; et al. (Jun 2013). "Effect of tight blood glucose control versus conventional control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Cardiovascular Therapeutics. 31 (3): 147–60. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5922.2011.00308.x. PMID 22212499.

^ Kastelan S, Zjacić-Rotkvić V, Kastelan Z (2007). "Could diabetic retinopathy be an autoimmune disease?". Med. Hypotheses. 68 (5): 1016–18. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.05.073. PMID 17125935.

^ Granberg V, Ejskjaer N, Peakman M, Sundkvist G (August 2005). "Autoantibodies to autonomic nerves associated with cardiac and peripheral autonomic neuropathy". Diabetes Care. 28 (8): 1959–64. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.8.1959. PMID 16043739.

^ Ichinose K, Kawasaki E, Eguchi K (2007). "Recent advancement of understanding pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes and potential relevance to diabetic nephropathy". Am. J. Nephrol. 27 (6): 554–64. doi:10.1159/000107758. PMID 17823503.

^ Adams DD (June 2008). "Autoimmune destruction of pericytes as the cause of diabetic retinopathy". Clin Ophthalmol. 2 (2): 295–98. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S2629. PMC 2693966. PMID 19668719.

^ Foss CH, Vestbo E, Frøland A, Gjessing HJ, Mogensen CE, Damsgaard EM (March 2001). "Autonomic neuropathy in nondiabetic offspring of type 2 diabetic subjects is associated with urinary albumin excretion rate and 24-h ambulatory blood pressure: the Fredericia Study". Diabetes. 50 (3): 630–36. doi:10.2337/diabetes.50.3.630. PMID 11246884.

^ Ban CR, Twigg SM (2008). "Fibrosis in diabetes complications: pathogenic mechanisms and circulating and urinary markers". Vasc Health Risk Manag. 4 (3): 575–96. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S1991. PMC 2515418. PMID 18827908.

^ Tarnow L, Groop PH, Hadjadj S, et al. (January 2008). "European rational approach for the genetics of diabetic complications—EURAGEDIC: patient populations and strategy". Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 23 (1): 161–68. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfm501. PMID 17704113.

^ Monti MC, Lonsdale JT, Montomoli C, et al. (December 2007). "Familial risk factors for microvascular complications and differential male-female risk in a large cohort of American families with type 1 diabetes". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92 (12): 4650–55. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-1185. PMID 17878250.

^ Liew G, Klein R, Wong TY (2009). "The role of genetics in susceptibility to diabetic retinopathy". Int Ophthalmol Clin. 49 (2): 35–52. doi:10.1097/IIO.0b013e31819fd5d7. PMC 2746819. PMID 19349785.

^ Mard-Soltani M, Dayer MR, Ataie G, et al. (April 2011). "Coagulation Factors Evaluation in NIDDM Patients". American Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 1 (3): 244–54. doi:10.3923/ajbmb.2011.244.254.

^ Mard-Soltani M, Dayer MR, Shamshirgar-Zadeh A, et al. (April 2012). "The Buffering Role of HDL in Balancing the Effects of Hypercoagulable State in Type 2 Diabetes". J Applied Sciences. 12 (8): 745–52. Bibcode:2012JApSc..12..745M. doi:10.3923/jas.2012.745.752.

^ P. Zaoui, et al, "Role of Metalloproteases and Inhibitors in the Occurrence and Prognosis of Diabetic Renal Lesions," Diabetes and Metabolism, vol. 26 (Supplement 4), p. 25 (2000)

^ Bonnefont-Rousselot D (2004). "The role of antioxidant micronutrients in the prevention of diabetic complications". Treatments in Endocrinology. 3 (1): 41–52. doi:10.2165/00024677-200403010-00005. PMID 15743112.

^ ab Arora, S., Lidor, A., Abularrage, C. J., Weiswasser, J. M., Nylen, E., Kellicut, D., et al. (2006). Thiamine (vitamin B-1) improves endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in the presence of hyperglycemia. Annals of Vascular Surgery, 20(5), 653–58

^ abc Thornalley, P. J. (2005). The potential role of thiamine (vitamin B1) in diabetic complications. Current Diabetes Reviews, 1(3), 287–98

^ ab Karachalias N.; Babaei-Jadidi R.; Rabbani N.; Thornalley P. J. (2010). "Increased protein damage in renal glomeruli, retina, nerve, plasma and urine and its prevention by thiamine and benfotiamine therapy in a rat model of diabetes". Diabetologia. 53 (7): 1506–16. doi:10.1007/s00125-010-1722-z. PMID 20369223.

^ Rabbani, N; Thornalley, PJ (July 2011). "Emerging role of thiamine therapy for prevention and treatment of early-stage diabetic nephropathy". Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism. 13 (7): 577–83. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01384.x. PMID 21342411.

^ Pflipsen M, Oh R, Saguil A, Seehusen D, Seaquist D, Topolski R (2009). "The prevalence of vitamin B12deficiency in patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study". The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 22 (5): 528–34. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2009.05.090044. PMID 19734399.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ ab Al-Maskari MY, Waly MI, Ali A, Al-Shuaibi YS, Ouhtit A (2012). "Folate and vitamin B12 deficiency and hyperhomocysteinemia promote oxidative stress in adult type 2 diabetes". Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.). 28 (7–8): e23–26. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2012.01.005.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ Selhub, J., Jacques, P., Dallal, G., Choumenkovitch, S., & Rogers, G. (2008). The use of blood concentrations of vitamins and their respective functional indicators to define folate and vitamin B12 status. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 29(s), 67–73

^ Mangoni AA, Sherwood RA, Asonganyi B, Swift CG, Thomas S, Jackson SHD (2005). "Short-term oral folic acid supplementation enhances endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes". American Journal of Hypertension. 18 (2): 220–26. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.08.036. PMID 15752950.

^ ab Mangoni AA, Sherwood RA, Swift CG, Jackson SHD (2002). "Folic acid enhances endothelial function and reduces blood pressure in smokers: A randomized controlled trial". Journal of Internal Medicine. 252 (6): 497–503. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01059.x. PMID 12472909.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ Mangoni AA, Jackson SHD (2002). "Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease: Current evidence and future prospects". American Journal of Medicine. 112 (7): 556–65. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01021-5.

^ Title LM, Ur E, Giddens K, McQueen MJ, Nassar BA (2006). "Folic acid improves endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes – an effect independent of homocysteine-lowering". Vascular Medicine. 11 (2): 101–09. doi:10.1191/1358863x06vm664oa. PMID 16886840.

^ Montezano, A. C., & Touyz, R. M. (2012). Reactive oxygen species and endothelial function - role of nitric oxide synthase uncoupling and nox family nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology, 110(1), 87–94

^ Van Etten R. W.; de Koning E. J. P.; Verhaar M. C.; et al. (2002). "Impaired NO-dependent vasodilation in patients with type II (non-insulin-dependent) by acute administration diabetes mellitus is restored of folate". Diabetologia. 45 (7): 1004–10. doi:10.1007/s00125-002-0862-1. PMID 12136399.

^ Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Larijani B, Abdollahi M (2005). "A review on the role of antioxidants in the management of diabetes and its complications". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 59 (7): 365–73. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2005.07.002.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ abc Song Y.; Cook N.; Albert C.; Denburgh M. V.; Manson J. E. (2009). "Effects of vitamins C and E and beta-carotene on the risk of type 2 diabetes in women at high risk of cardiovascular disease: A randomized controlled trial". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 90 (2): 429–37. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.27491. PMC 2848361. PMID 19491386.

^ ab Sargeant L. A.; Wareham N. J.; Bingham S.; et al. (2000). "Vitamin C and hyperglycemia in the european prospective investigation into cancer – norfolk (EPIC-norfolk) study – A population-based study". Diabetes Care. 23 (6): 726–32. doi:10.2337/diacare.23.6.726.

^ Deshpande A., Hayes M., Schootman M. (2008). "Epidemiology of diabetes and diabetes-related complications". Physical Therapy. 88 (11): 1254–64. doi:10.2522/ptj.20080020. PMC 3870323. PMID 18801858.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ Kataja-Tuomola M.; Sundell J.; Männistö S.; Virtanen M.; Kontto J.; Albanes D.; et al. (2008). "Effect of alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene supplementation on the incidence of type 2 diabetes". Diabetologia. 51 (1): 47–53. doi:10.1007/s00125-007-0864-0. PMID 17994292.

^ Ceriello A, Novials A, Ortega E, Canivell S, Pujadas G, La Sala L, et al. (2013). "Vitamin C further improves the protective effect of GLP-1 on the ischemia-reperfusion-like effect induced by hyperglycemia post-hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes". Cardiovascular Diabetology. 12: 97. doi:10.1186/1475-2840-12-97. PMC 3699412. PMID 23806096.

^ abc Afkhami-Ardekani M, Shojaoddiny-Ardekani A (2007). "Effect of vitamin C on blood glucose, serum lipids & serum insulin in type 2 diabetes patients". Indian Journal of Medical Research. 126 (5): 471–74.

^ abc Sugden J. A., Davies J. I., Witham M. D., Morris A. D., Struthers A. D. (2008). "Vitamin D improves endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and low vitamin D levels". Diabetic Medicine. 25 (3): 320–325. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02360.x.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ ab Takiishi T., Gysemans C., Bouillon R., Mathieu C. (2010). "Vitamin D and diabetes". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 39 (2): 419–46. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2010.02.013. PMID 20511061.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ Talaei A., Mohamadi M., Adgi Z. (2013). "The effect of vitamin D on insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes". Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome. 5 (8). doi:10.1186/1758-5996-5-8. PMID 23443033.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ Takiishi T., Gysemans C., Bouillon R., Mathieu C. (2010). "Vitamin D and diabete:". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 39 (2): 419–46. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2010.02.013.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ Muthian G, Raikwar HP, Rajasingh J, Bright JJ (2006). "1,25 dihydroxyvitamin-D3 modulates JAK-STAT pathway in IL-12/IFN gamma axis leading to Th1 response in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 83 (7): 1299–309. doi:10.1002/jnr.20826.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ Gannage-Yared MH, Azoury M, Mansour I, Baddoura R, Halaby G, Naaman R (2003). "Effects of a short-term calcium and vitamin D treatment on serum cytokines, bone markers, insulin and lipid concentrations in healthy post-menopausal women". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 26 (8): 748–53. doi:10.1007/bf03347358.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ Mullan B. A.; Young I. S.; Fee H.; McCance D. R. (2002). "Ascorbic acid reduces blood pressure and arterial stiffness in type 2 diabetes". Hypertension. 40 (6): 804–09. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.538.5875. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.0000039961.13718.00.

^ Regensteiner J. G.; Popylisen S.; Bauer T. A.; Lindenfeld J.; Gill E.; Smith S.; et al. (2003). "Oral L-arginine and vitamins E and C improve endothelial function in women with type 2 diabetes". Vascular Medicine. 8 (3): 169–75. doi:10.1191/1358863x03vm489oa.

External links

| Classification | D

|

|---|