Hopewell tradition

Hopewell Interaction Area and local expressions of the Hopewell tradition

The Hopewell tradition (also called the Hopewell culture) describes the common aspects of the Native American culture that flourished along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern United States from 100 BCE to 500 CE, in the Middle Woodland period. The Hopewell tradition was not a single culture or society, but a widely dispersed set of related populations. They were connected by a common network of trade routes,[1] known as the Hopewell exchange system.

At its greatest extent, the Hopewell exchange system ran from the Crystal River Indian Mounds in modern-day Florida as far north as the Canadian shores of Lake Ontario. Within this area, societies participated in a high degree of exchange with the highest amount of activity along waterways. The Hopewell exchange system received materials from all over what is now the United States. Most of the items traded were exotic materials and were received by people living in the major trading and manufacturing areas. These people then converted the materials into products and exported them through local and regional exchange networks. The objects created by the Hopewell exchange system spread far and wide and have been seen in many burials outside the Midwest.[2]

Contents

1 Origins

2 Politics and hierarchy

3 Mounds

4 Artwork

5 Local expressions of Hopewellian traditions

5.1 Armstrong culture

5.2 Copena culture

5.3 Crab Orchard culture

5.4 Goodall focus

5.5 Havana Hopewell culture

5.6 Kansas City Hopewell

5.7 Laurel complex

5.8 Marksville culture

5.9 Miller culture

5.10 Montane Hopewell

5.11 Ohio Hopewell culture

5.12 Point Peninsula complex

5.13 Saugeen complex

5.14 Swift Creek culture

5.15 Wilhelm culture

6 Cultural decline

6.1 Genetic studies

7 See also

8 Further reading

9 References

10 External links

Origins

Although the origins of the Hopewell are still under discussion, the Hopewell culture can also be considered a cultural climax.

Hopewell populations originated in western New York and moved south into Ohio, where they built upon the local Adena mortuary tradition. Or, Hopewell was said to have originated in western Illinois and spread by diffusion ... to southern Ohio. Similarly, the Havana Hopewell tradition was thought to have spread up the Illinois River and into southwestern Michigan, spawning Goodall Hopewell. (Dancey 114)

The name "Hopewell" was applied by Warren K. Moorehead after his explorations of the Hopewell Mound Group in Ross County, Ohio, in 1891 and 1892. The mound group itself was named for the family who owned the earthworks at the time. What any of the various groups now defined as Hopewellian called themselves is unknown.[3][4] It is used to describe a wide scattering of people who lived near rivers in temporary settlements of 1-3 households and practiced a mixture of hunting, gathering and crop growing.[5]

Politics and hierarchy

The Hopewell inherited from their Adena forebears an incipient social stratification. This increased social stability and reinforced sedentism, social stratification, specialized use of resources, and probably population growth.[6] Hopewell societies cremated most of their deceased and reserved burial for only the most important people. In some sites, hunters apparently received a higher status in the community because their graves were more elaborate and contained more status goods.[7]

The Hopewellian peoples had leaders, but they were not like powerful rulers who could command armies of slaves and soldiers.[3] These cultures likely accorded certain families a special place of privilege. Some scholars suggest that these societies were marked by the emergence of "big-men".[8] These leaders acquired their position because of their ability to persuade others to agree with them on important matters such as trade and religion. They also perhaps were able to develop influence by the creation of reciprocal obligations with other important members of the community. Whatever the source of their status and power, the emergence of "big-men" was another step toward the development of the highly structured and stratified sociopolitical organization called the chiefdom.[7]

The Hopewell settlements were linked by extensive and complex trading routes, which doubled as communication networks, bring people together for important ceremonies.[5]

Mounds

Hopewell mounds from the Mound City Group in Ohio

Today, the best-surviving features of the Hopewell tradition era are mounds built for uncertain purposes. Great geometric earthworks are one of the most impressive Native American monuments throughout American prehistory. Eastern Woodlands mounds have various geometric shapes and rise to impressive heights. The gigantic sculpted earthworks often took the shape of animals, birds, or writhing serpents.[9] The function of the mounds is still under debate. Due to considerable evidence and surveys, plus the good survival condition of the largest mounds, more information can be obtained.

Several scientists, including Dr. Bradley T. Lepper, Curator of Archaeology, Ohio Historical Society, hypothesize that the Octagon earthwork at Newark, Ohio, was a lunar observatory oriented to the 18.6-year cycle of minimum and maximum lunar risings and settings on the local horizon. The Octagon covers more than 50 acres, the size of 100 football pitches[5]. Dr. John Eddy completed an unpublished survey in 1978, and proposed a lunar major alignment for the Octagon. Ray Hively and Robert Horn of Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, were the first researchers to analyze numerous lunar sightlines at the Newark Earthworks (1982) and the High Banks Works (1984) in Chillicothe, Ohio.[10] Christopher Turner noted that the Fairground Circle in Newark, Ohio aligns to the sunrise on May 4, i.e. that it marked the May cross-quarter sunrise.[11] In 1983, Turner demonstrated that the Hopeton earthworks encode various sunrise and moonrise patterns, including the winter and summer solstices, the equinoxes, the cross-quarter days, the lunar maximum events, and the lunar minimum events due to their precise straight and parallel lines.[12][5]

William F. Romain has written a book on the subject of "astronomers, geometers, and magicians" at the earthworks.[13]

Many of the mounds also contain various types of burials. Precious burial good have also been found in the mounds. These include objects of adornment made of copper, mica and obsidian, imported to the region hundreds of miles away. Stone and ceramics were also fashioned into intricate shapes.

Artwork

The Hopewell created some of the finest craftwork and artwork of the Americas. Most of their works had some religious significance, and their graves were filled with necklaces, ornate carvings made from bone or wood, decorated ceremonial pottery, ear plugs, and pendants. Some graves were lined with woven mats, mica (a mineral consisting of thin glassy sheets), or stones.[14] The Hopewell produced artwork in a greater variety and with more exotic materials than their predecessors the Adena. Grizzly bear teeth, fresh water pearls, sea shells, sharks' teeth, copper and even small quantities of silver were turned into beautifully crafted pieces. The Hopewell artisans were expert carvers of pipestone, and many of the mortuary mounds are full of exquisitely carved statues and pipes.[15] The Mound of Pipes at Mound City produced over 200 stone smoking pipes depicting animals and birds in well-realized three-dimensional form,[16] and the Tremper Site in Scioto County produced over 130.[17] Some artwork went beyond the ordinary exotic, as Hopewell artists were expert carvers of human bone. A rare mask from Mound City was created using a human skull as a face plate.[15]

Hopewell artists created both abstract and realistic portrayals of the human form. One tubular pipe is so realistically portrayed that the model was identified as an achondroplastic (chondrodystropic) dwarf.[18] Many other figurines give details of dress, ornamentation, and hairstyles.[15] An example of their abstract human forms is the "Mica Hand" from the Hopewell Site in Ross County, Ohio. Delicately cut from a piece of mica, more than 11 inches long, and 6 inches wide, the hand piece was likely worn or carried for public viewing.[15]

Carved mica hand, Hopewell Mounds

Serpent effigy, Turner Group, Mound 4, Little Miami Valley, OH

Hopewell pipe, points, and earspool on display at Serpent Mound

Gorgets and points from the Adena culture, found at Serpent Mound

Raven effigy pipe, Mound City

Otter effigy pipe, Mound City

Bird figure, Tremper Mounds

Copper spider(?) from a Ross County mound

Bird head carved on bone, Hopewell Mounds

Repoussé copper falcon, Mound City

Repoussé copper falcon at American Museum of Natural History

Pot with a bird design, Hopewell site

Local expressions of Hopewellian traditions

Aside from the more famous Ohio Hopewell, a number of other Middle Woodland period cultures are known to have been involved in the Hopewell tradition and participated in the Hopewell exchange network.

Armstrong culture

The Armstrong culture was a Hopewell group in the Big Sandy River Valley of northeastern Kentucky and western West Virginia from 1 to 500 CE. They are thought to have been a regional variant of the Hopewell tradition or a Hopewell-influenced Middle Woodland group who had peacefully mingled with the local Adena peoples.[19] Archaeologist Dr. Edward McMichael characterized them as an intrusive Hopewell-like trade culture or a vanguard of Hopewellian tradition that had probably peacefully absorbed the local Adena in the Kanawha River Valley. Their culture and very Late Adena (46PU2) is currently thought to have slowly evolved into the later Buck Garden people.[20]

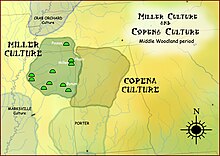

Copena culture

The Copena culture was a Hopewellian culture in northern Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee, as well as in other sections of the surrounding region including Kentucky. The Copena name is derived from the first three letters of copper and the last three letters of the mineral galena. Copper and galena artifacts are often associated with Copena burials.[21]

Crab Orchard culture

Crab Orchard culture

During the Middle Woodland period, the Crab Orchard culture population increased from a dispersed and sparsely settled Early Woodland pattern to one consisting of small and large base camps. These were concentrated on terrace and floodplain landforms associated with the Ohio River channel in southern Indiana, southern Illinois, and northwestern and western Kentucky.[22] In the far western limits of Crab Orchard culture is the O'byams Fort site, a large tuning fork-shaped earthwork reminiscent of Ohio Hopewell enclosures.[23] Examples of a type of pottery decoration found at the Mann Site are also known from Hopewell sites in Ohio (such as Seip earthworks, Rockhold, Harness, and Turner), as well as from Southeastern sites with Hopewellian assemblages such as the Miner's Creek site, Leake Mounds, 9HY98, and Mandeville Site in Georgia, and the Yearwood site in southern Tennessee.[24]

Goodall focus

The Goodall focus occupied Michigan and northern Indiana from around 200 BCE to 500 CE. The Goodall pattern stretched from the southern tip of Lake Michigan, east across northern Indiana, to the Ohio border, then northward, covering central Michigan, almost reaching to Saginaw Bay on the east and Grand Traverse Bay to the north. The culture is named for the Goodall site in northwest Indiana.[25]

Havana Hopewell culture

The Havana Hopewell culture was a Hopewellian people in the Illinois River and Mississippi River valleys in Iowa, Illinois, and Missouri. They are ancestral to the groups which eventually became the Mississippian culture of Cahokia and its hinterlands.

The Toolesboro site is a group of seven burial mounds on a bluff overlooking the Iowa River near where it joins the Mississippi River. The conical mounds were constructed between 100 BCE and 200 CE. At one time, as many as 12 mounds may have existed. Mound 2, the largest remaining, measures 100 feet in diameter and 8 feet in height. This mound was possibly the largest Hopewell mound in Iowa.[26]

Kansas City Hopewell

At the western edge of the Hopewell interaction sphere is the Kansas City Hopewell. The Renner Village archeological site in Riverside, Missouri, is one of several sites near the junction of Line Creek and the Missouri River. The site contains Hopewell and Middle Mississippian remains. The Trowbridge archeological site near Kansas City is close to the western limit of the Hopewell, "Hopewell-style" pottery and stone tools, typical of the Illinois and Ohio River Valleys, are abundant at the Trowbridge site, and decorated Hopewell-style pottery rarely appears further west.[27] The Cloverdale site is situated at the mouth of a small valley that opens into the Missouri River Valley, near Saint Joseph, Missouri. It is a multicomponent site with Kansas City Hopewell (around 100 to 500 CE) and Steed-Kisker (around 1200 CE) occupation.[28]

Laurel complex

The Laurel complex was a Native American culture in southern Quebec, southern and northwestern Ontario, and east-central Manitoba in Canada and northern Michigan, northwestern Wisconsin and northern Minnesota in the United States. They were the first pottery-using people of Ontario north of the Trent-Severn Waterway. The complex is named after the former unincorporated community of Laurel, Minnesota.

Marksville culture

The Marksville culture was a Hopewellian culture in the Lower Mississippi valley, Yazoo valley, and Tensas valley areas of Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Arkansas. It evolved into the Baytown culture and later the Coles Creek and Plum Bayou cultures. It is named for the Marksville Prehistoric Indian Site in Marksville, Louisiana.[29]

Miller culture

Miller and Copena cultures

The Miller culture was a Hopewellian culture located in the upper Tombigbee River drainage areas of southwestern Tennessee, northeastern Mississippi, and west-central Alabama, best known from excavations at the Pinson Mounds, Bynum Mounds, Miller (type site), and Pharr Mounds sites.[30][31] The culture is divided chronologically into two phases, Miller 1 and Miller 2, with a later Miller 3 belonging to the Late Woodland period. Some sites associated with the Miller culture, such as Ingomar Mound and Pinson Mounds on its western periphery, built large platform mounds. Archaeologist speculate the mounds were for feasting rituals and that they fundamentally differed from later Mississippian culture platform mounds which were mortuary and substructure platforms.[31] By then end of the Late Woodland period, about 1000, the Miller culture area was absorbed into the succeeding Mississippian culture.[32]

Montane Hopewell

The Montane Hopewell on the Tygart Valley area, an upper branch of the Monongahela River, of northern West Virginia, are similar to Armstrong. The pottery and cultural characteristics are also similar to late Ohio Hopewell.[20] They occurred during the neighboring Watson through Buck Garden periods to their south and westerly in the state. Montane Hopwell are of a considerable distance variant from Cole Culture and Peters Phase or Hopewell central Ohio. However, this Hopewellian arrival of a particular small, conical mound religion appears to be also waning to the daily living activities at these sites according to Dr McMichael. This period begins a rapid fading away of influence by an elite priest cult burial phase centered towards the Midwest states.[19]

Ohio Hopewell culture

| Preceded by Adena culture | Ohio Hopewell 200 BCE-500 CE | Succeeded by Fort Ancient |

Map of the Archaeological Cultures of Ohio

The greatest concentration of Hopewell ceremonial sites is in the Scioto River Valley (from Columbus to Portsmouth, Ohio) and adjacent Paint Creek, centered on Chillicothe, Ohio. These cultural centers typically contain a burial mound and a geometric earthwork complex that covers ten to hundreds of acres and sparse settlements; evidence of large resident populations is lacking at the monument complexes.[33] The Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, encompassing mounds for which the culture is named, is in the Paint Creek Valley just a few miles from Chillicothe, Ohio. Other earthworks in the Chillicothe area include Hopeton, Mound City, Seip Earthworks and Dill Mounds District, High Banks Works, Liberty, Cedar-Bank Works, Anderson, Frankfort, Dunlap, Spruce Hill, and Story Mound.[34]

When colonial settlers first crossed the Appalachians, after almost a century and a half in North America, they were astounded at these monumental constructions, some reaching as high as 70 feet.[9]

The Portsmouth Earthworks were constructed from 100 BCE to 500 CE. It is a large ceremonial center located at the confluence of the Scioto and Ohio Rivers. Part of this earthwork complex extends across the Ohio River into Kentucky. The earthworks included a northern section consisting of a number of circular enclosures, two large, horseshoe-shaped enclosures, and three sets of parallel-walled roads leading away from this location. One set of walls went to the southwest and may have linked to a large square enclosure located on the Kentucky side of the Ohio River. Another set went to the southeast, where it crossed the Ohio River and continued to the Biggs site, a complicated circular enclosure surrounding a conical mound. The third set of walls went to the northwest for an undetermined distance, in the direction of the Tremper site.[23][35]

Point Peninsula complex

The Point Peninsula complex was a Native American culture located in Ontario and New York during the Middle Woodland period, thought to have been influenced by the Hopewell traditions of the Ohio River valley. This influence seems to have ended about 250 CE, after which burial ceremonialism was no longer practiced.[36]

Saugeen complex

The Saugeen complex was a Native American culture located around the southeast shores of Lake Huron and the Bruce Peninsula, around the London area, and possibly as far east as the Grand River. Some evidence exists that the Saugeen complex people of the Bruce Peninsula may have evolved into the Odawa people (Ottawa).[36]

Swift Creek culture

The Swift Creek culture was a Middle Woodland period archaeological culture in Georgia, Alabama, Florida, South Carolina, and Tennessee dating to around 100–700 CE.

Wilhelm culture

The Wilhelm culture (1 to 500 CE), Hopewellian influenced, appeared in the northern panhandle of West Virginia. They were contemporaneous to Armstrong central on the Big Sandy valley nearly 200 miles downstream on the Ohio River. They were surrounded by peoples who made the Watson-styled pottery, with a Z-twist cordage finished surface.[37] Wilhelm pottery was similar to Armstrong pottery, but not as well made.[20] Pipe fragments appear to be the platform-base type. Small mounds were built around individual burials in stone-lined graves (cists). These were covered over together under a single large mound.[38]

Little studied are their four reported village sites,[20] which appear to have been abandoned by about 500 CE. Today, new local researchers are looking at this area period and may provide future insight.[39]

Cultural decline

Sinnissippi Mounds, Sinnissippi Park, Sterling, Illinois

Around 500 CE, the Hopewell exchange ceased, mound building stopped, and art forms were no longer produced. War is a possible cause, as villages dating to the Late Woodland period shifted to larger communities; they built defensive fortifications of palisade walls and ditches.[40] Colder climatic conditions could have also driven game animals north or west, as weather would have a detrimental effect on plant life, drastically cutting the subsistence base for these foods. The introduction of the bow and arrow, by improving hunts, may have caused stress on already depleted food populations. It may have led people to live in larger, more permanent communities for protection as warfare became more deadly. With fewer people using trade routes, there was no longer a network linking people to the Hopewell traditions.[5] The breakdown in societal organization could also have been the result of full-scale agriculture.[41] Conclusive reasons for the evident dispersal of the people have not yet been determined.

| Preceded by Early Woodland period Adena culture | Hopewell tradition 200 BCE – 500 CE | Succeeded by Late Woodland |

Genetic studies

Modern studies show that 80% of cranial samples from Hopewell remains indicate a cephalic index in the range of being dolicocephalic. Analysis of Hopewell remains indicate shared mtDNA mutations unique with lineages from China, Korea, Japan, and Mongolia,[42] while bone collagen from Eastern North American native remains indicate maize was not a large part of their diet until after B.P. 1000. As of 2003, maize had only been discovered at one archaeological dig site in Ohio.[42]

See also

- List of Hopewell sites

- Adena culture

Further reading

- A. Martin Byers and DeeAnne Wymer, eds. Hopewell Settlement Patterns, Subsistence, and Symbolic Landscapes (University Press of Florida, 2010); 400 pages

References

^ Douglas T. Price; Gary M. Feinman (2008). Images of the Past, 5th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 274–277. ISBN 978-0-07-340520-9..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Fagan, Brian M. (2005). Ancient North America. Thames and Hudson, London.

^ ab "Hopewell Culture". Ohio History Central. Ohio Historical Society. Retrieved 2011-05-25.

^ "Hopewell Mound Group". Ohio History Central. Ohio Historical Society. Retrieved 2011-05-25.

^ abcde Nelson, Jo (2015). Historium. Big Pictures Press. p. 32.

^ Brose, D. (1979). "A speculative model of the roles of exchange in the prehistory of the eastern Woodlands". In D. Brose & N. Gerber. Hopewellian Archaeology. Kent University Press. pp. 3–8.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

^ ab "Native American Government-Eastern Woodlands".

^ Smith, B.D. (1986). The Archaeology of the southeastern United States: from Dalton to de Soto, 10,500 to 500 BP. Advances in World Archaeology 5. University of Georgia Press. pp. 1–92.

^ ab Nash, Gary B. Red, White and Black: The Peoples of Early North America Los Angeles 2015. Chapter 1, p. 6.

^ "The Octagon Earthworks: A Neolithic Lunar Observatory". Archived from the original on 2008-01-11. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

^ Turner, Christopher S. (1982). "Hopewell Archaeoastronomy". Archaeoastronomy Journal. 5(n3). University Press of Kentucky. p. -9.

^ Turner, Christopher S. (1983). An Astronomical Interpretation of the Hopeton Earthworks. C.S.Turner.

^ "Newark Earthwork Cosmology".

^ "Ancestral Art-Information on Hopewell Culture". Archived from the original on 2008-09-05. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

^ abcd Power, Susan (2004). Early Art of the Southeastern Indians – Feathered Serpents and Winged Beings. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-2501-5.

^ "Hopewell (1–400 A.D.)". Retrieved 2008-09-11.

^ "Tremper Mound and Earthworks-Ohio History Central". Retrieved 2009-06-02.

^ "A Survey of Adena-Hopewell (Scioto) Anthropomorphic Portraiture" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-06. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

^ ab Dragoo, Don W. (1963). Mounds for the Dead. Annals of the Carnegie Museum. 37. Woodward and McDonald; Carnegie Museum. ISBN 978-0-911239-09-6.

^ abcd McMichael, Edward V. (1968). Introduction to West Virginia Archeology (2 ed.). West Virginia Archeological Society.

^ "Copena". Archived from the original on 2007-01-25. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

^ Ian K. deNeeve. "Midwest Archaeological Conference". Archived from the original on 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

^ ab Lewis, R. Barry (1996). Kentucky Archaeology. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1907-3.

^ "Excavation and Archaeological Investigation at Barstow County's Leake Site-Evidence for Interaction". Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

^ Hopewell Archeology: The Newsletter of Hopewell Archeology in the Ohio River Valley; 4. Current Research on the Goodall Focus; Volume 2, Number 1, October 1996

^ "Toolesboro Mounds History". Archived from the original on 2008-01-24. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

^ "Trowbridge (14WY1) is an archaeological site located near Kansas City, Kansas". Retrieved 2008-09-12.

^ "Talk-Hopewell Tradition". Archived from the original on 2008-07-26. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

^ "Louisiana Prehistory-Marksville". Archived from the original on February 23, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

^ Gibbon, Guy E.; Ames, Kenneth M. (eds.). Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: an encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 527–528. ISBN 978-0-8153-0725-9.

^ ab Gibbon, Guy E.; Ames, Kenneth M. (eds.). Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: an encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 327–328. ISBN 978-0-8153-0725-9.

^ "Southeastern Prehistory : Late Woodland Period". NPS.GOV. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

^ "m7/98 Encyclopedia of North American Prehistory M". Archived from the original on 2009-10-25. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

^ "Chillicothe Earthworks-Ohio Central History". Retrieved 2008-09-11.

^ "Portsmouth Earthworks-Ohio Central History". Retrieved 2008-09-11.

^ ab "The Archaeology of Ontario-The Middle Woodland Period". Archived from the original on 2009-07-15. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

^ Peterson map 5.1 1996-08:91; Maslowski 1973, 1978a, 1980, 1984a: "Cordage Twist and Ethnicity"

^ Rice, and Brown (1993). West Virginia, a history. 2. University Press of Kentucky; Google eBook. ISBN 978-0-911239-09-6.

^ William C. Johnson,, D. Scott Speedy (2009). Grave Creek Mound Archaeology Complex Research Facility and Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology (abstract ed.). West Virginia Archeological Society.

^ Ohio History Central http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=1283

^ "Free Essays-Hopewell Indian Culture". Archived from the original on 2008-08-27. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

^ ab "ETD Home". etd.OhioLink.edu. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hopewell culture. |

- Ohio Historical Society's Archaeology Page

- Ancient Earthworks of Eastern North America

- Octagon Moonrise website

- Ohio Memory