Nine Years' War

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .mobile-float-reset{float:none!important;width:100%!important}}.mw-parser-output .stack-container{box-sizing:border-box}.mw-parser-output .stack-clear-left{float:left;clear:left}.mw-parser-output .stack-clear-right{float:right;clear:right}.mw-parser-output .stack-left{float:left}.mw-parser-output .stack-right{float:right}.mw-parser-output .stack-object{margin:1px;overflow:hidden}

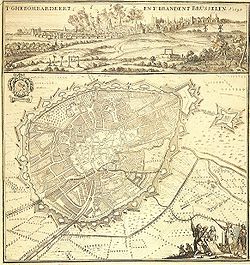

The Nine Years' War (1688–97)—often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg[2]—was a conflict between Louis XIV of France and a European coalition of the Holy Roman Empire (led by Austria), the Dutch Republic, Spain, England and Savoy. It was fought in Europe and the surrounding seas, North America and in India. It is sometimes considered the first global war. The conflict encompassed the Williamite war in Ireland and Jacobite risings in Scotland, where William III and James II struggled for control of England and Ireland, and a campaign in colonial North America between French and English settlers and their respective Indigenous allies, today called King William's War by Americans.

Louis XIV of France had emerged from the Franco-Dutch War in 1678 as the most powerful monarch in Europe, an absolute ruler who had won numerous military victories. Using a combination of aggression, annexation, and quasi-legal means, Louis XIV set about extending his gains to stabilize and strengthen France's frontiers, culminating in the brief War of the Reunions (1683–84). The Truce of Ratisbon guaranteed France's new borders for twenty years, but Louis XIV's subsequent actions—notably his Edict of Fontainebleau (the revocation of the Edict of Nantes) in 1685— led to the deterioration of his military and political dominance. Louis XIV's decision to cross the Rhine in September 1688 was designed to extend his influence and pressure the Holy Roman Empire into accepting his territorial and dynastic claims. Leopold I and the German princes resolved to resist, and when the States General and William III brought the Dutch and the English into the war against France, the French king faced a powerful coalition aimed at curtailing his ambitions.

The main fighting took place around France's borders in the Spanish Netherlands, the Rhineland, the Duchy of Savoy and Catalonia. The fighting generally favoured Louis XIV's armies, but by 1696 his country was in the grip of an economic crisis. The Maritime Powers (England and the Dutch Republic) were also financially exhausted, and when Savoy defected from the Alliance, all parties were keen to negotiate a settlement. By the terms of the Treaty of Ryswick (1697) Louis XIV retained the whole of Alsace but was forced to return Lorraine to its ruler and give up any gains on the right bank of the Rhine. Louis XIV also accepted William III as the rightful King of England, while the Dutch acquired a Barrier fortress system in the Spanish Netherlands to help secure their borders. With the ailing and childless Charles II of Spain approaching his end, a new conflict over the inheritance of the Spanish Empire embroiled Louis XIV and the Grand Alliance in the War of the Spanish Succession.

Contents

1 Background 1678–87

1.1 Reunions

1.2 Fighting on two fronts

1.3 Persecution of the Huguenots

2 Prelude: 1687–88

3 Nine years of war: 1689–97

3.1 Rhineland and the Empire

3.2 Britain

3.3 Ireland

3.4 War aims and the Grand Alliance

3.5 Expanding war: 1690–91

3.6 Heavy fighting: 1692–93

3.7 War and diplomacy: 1694–95

3.8 Road to Ryswick: 1696–97

4 North American theatre (King William's War)

5 Asia and the Caribbean

6 Treaty of Ryswick

7 Weapons, technology, and the art of war

7.1 Military developments

7.2 Naval developments

8 Notes

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

Background 1678–87

In the years following the Franco-Dutch War (1672–78) Louis XIV of France – now at the height of his powers – sought to impose religious unity in France, and to solidify and expand his frontiers. Louis XIV had already won his personal glory by conquering new territory, but he was no longer willing to pursue an open-ended militarist policy of the kind he had undertaken in 1672, and instead relied upon France's clear military superiority to achieve specific strategic objectives along his borders. Proclaimed the 'Sun King', a more mature Louis – conscious he had failed to achieve decisive results against the Dutch – had turned from conquest to security, using threats rather than open war to intimidate his neighbours into submission.[3]

Louis XIV, along with his chief advisor Louvois, his foreign minister Colbert de Croissy, and his technical expert, Vauban, developed France's defensive strategy.[4] Vauban had advocated a system of impregnable fortresses along the frontier that would keep France's enemies out. To construct a proper system, however, the King needed to acquire more land from his neighbours to form a solid forward line. This rationalisation of the frontier would make it far more defensible while defining it more clearly in a political sense, yet it also created the paradox that while Louis's ultimate goals were defensive, he pursued them by hostile means.[4] The King grabbed the necessary territory through what is known as the Réunions: a strategy that combined legalism, arrogance, and aggression.[5]

Reunions

Equestrian Portrait of Louis XIV (1638–1715) by René-Antoine Houasse. The 'Sun King' was the most powerful monarch in Europe.

The Treaty of Nijmegen (1678) and the earlier Treaty of Westphalia (1648) provided Louis XIV with the justification for the Reunions. These treaties had awarded France territorial gains, but because of the vagaries of the language (as with most treaties of the period) they were notoriously imprecise and self-contradictory, and never specified exact boundary lines. This imprecision often led to differing interpretations of the text resulting in long-standing disputes over the frontier zones – one gained a town or area and its 'dependencies', but it was often unclear what these dependencies were.[4] The machinery needed to determine these territorial ambiguities was already in place through the medium of the Parlements at Metz (technically the only 'Chamber of Reunion'), Besançon, and a superior court at Breisach, dealing respectively with Lorraine, Franche-Comté, and Alsace.[6] Unsurprisingly, these courts usually found in Louis XIV's favour.[7] By 1680 the disputed County of Montbéliard (lying between Franche-Comté and Alsace) had been separated from the Duchy of Württemberg, and by August, Louis XIV had secured the whole of Alsace with the exception of Strasbourg. The Chamber of Reunion of Metz soon laid claims to land around the Three Bishoprics of Metz, Toul, and Verdun, and most of the Spanish Duchy of Luxembourg. The fortress of Luxembourg itself was subsequently blockaded with the intention of it becoming part of Louis XIV's defensible frontier.[8]

Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I (1640–1705), artist unknown

On 30 September 1681, French troops also seized Strasbourg and its outpost, Kehl, on the right bank of the Rhine, a bridge which Holy Roman Empire ("Imperial") troops had regularly exploited during the latter stages of the Dutch War.[9] By forcibly taking the Imperial city the French now controlled two of the three bridgeheads over the Rhine (the others being Breisach, which was already in French hands, and Philippsburg, which Louis XIV had lost by the Treaty of Nijmegen). On the same day that Strasbourg fell French forces marched into Casale in northern Italy.[10] The fortress was not taken through the process of the Reunions but had earlier been purchased from the Duke of Mantua, which, together with the French possession of Pinerolo, enabled France to tie down Victor Amadeus II, the Duke of Savoy, and threaten the Spanish Duchy of Milan (see map below).[11] All Reunion claims and annexations were important strategic points of entry and exit between France and its neighbours, and all were immediately fortified by Vauban and incorporated into his fortress system.[12]

Thus, the Reunions were carving territory from the frontiers of future Germany, while annexations were establishing French power in Italy. Yet by seeking to construct his impregnable border, Louis XIV so alarmed the other European states that he made the war he sought to avoid inevitable: his fortresses not only covered his frontiers, they projected French power.[13] Only two statesmen might hope to oppose Louis XIV: William of Orange, Stadtholder of the United Provinces of the Dutch Republic and the natural leader of Protestant opposition; and Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, obvious leader of anti-French forces in the Holy Roman Empire and Catholic Europe.[14] But while William and Leopold I wanted to act, effective opposition in 1681–82 was out of the question: Amsterdam's burghers wanted no further conflict with France; moreover, Leopold I and William were fully aware of the current weaknesses, not only of Spain, but also the Empire, whose important German princes from Mainz, Trier, Cologne, Saxony, Bavaria and, significantly, Frederick William I of Brandenburg, remained in French pay.[15]

Fighting on two fronts

Since Leopold I's intervention in the Franco-Dutch War Louis XIV had considered the Emperor his most dangerous enemy; yet the French king had little reason to fear him.[15] Leopold I was weak, and was in grave danger along his Hungarian borders where the Ottoman Turks were threatening to overrun all central Europe from the south. Louis had encouraged and assisted the Ottoman drive against Leopold I's Habsburg lands, and had assured the Porte that he would not support the Emperor. He had also urged Jan Sobieski of Poland (unsuccessfully) not to side with Leopold I, and pressed the malcontent princes of Transylvania and Hungary to join with the Sultan's forces and free their territory from Habsburg rule.[16] When the Turks besieged Vienna in the spring of 1683 Louis did nothing to help the defenders.[17]

Taking advantage of the Ottoman threat in the east Louis XIV invaded the Spanish Netherlands on 1 September 1683 and renewed the siege of Luxembourg, which had been abandoned the previous year.[18] The French required of the Emperor and Charles II of Spain a recognition of the legality of the recent Reunions, but the Spanish were unwilling to see any more of their holdings fall under Louis's jurisdiction.[19] Spain's military options were highly limited, yet the Ottoman defeat before Vienna on 12 September had emboldened them. In the hope that Leopold I would now make peace in the east and come to their assistance, Charles II declared war on France on 26 October. However, the Emperor had decided to continue the Turkish war in the Balkans and, for the time being, compromise in the west. With Leopold I unwilling to fight on two fronts; with a strong neutralist party in the Dutch Republic tying William's hands; and with the Elector of Brandenburg stubbornly holding to his alliance with Louis, there was no possible outcome but complete French victory.[20]

The War of the Reunions was brief and devastating. With the fall of Courtrai in early November 1683, followed by Dixmude in December and Luxembourg in June 1684, Charles II was compelled to accept Louis XIV's peace deal.[21] The Truce of Ratisbon (Regensburg) signed on 15 August by France on one side and the Emperor and Spain on the other, rewarded the French with Strasbourg, Luxembourg and the Reunion gains (Courtrai and Dixmude returned to Spain). The resolution was not a definitive peace, but only a truce for 20 years. Yet Louis had sound reasons to feel satisfied: the Emperor and German princes were fully occupied in Hungary—while in the Dutch Republic, William of Orange remained isolated and powerless, largely because of the pro-French mood in Amsterdam.[22]

Persecution of the Huguenots

William of Orange (1650–1702), portrayed here as King William III of England by Sir Godfrey Kneller.

At Ratisbon in 1684 France had been in a position to impose its will on Europe; however, after 1685 its dominant military and diplomatic position began to deteriorate. One of the main factors for this diminution was Louis XIV's revocation of the Edict of Nantes and the subsequent dispersal of France's Protestant community.[23] As many as 200,000 Huguenots fled to England, the Dutch Republic, Switzerland, and Germany, spreading tales of brutality at the hands of the monarch of Versailles. The direct effect on France of the loss of this community is debatable, but the flight helped destroy the pro-French group in the Dutch Republic, not only because of their Protestant affiliations, but with the exodus of Huguenot merchants and the harassment of Dutch merchants living in France, it also greatly affected Franco-Dutch trade.[24] The persecution had another effect on Dutch public opinion – the conduct of the Catholic King of France made them look more anxiously at James II, now the Catholic King of England. Many in The Hague believed James II was closer to his cousin Louis XIV than to his son-in-law and nephew William, thus engendering suspicion, and in turn hostility, between the two states.[25] Louis's seemingly endless territorial claims, coupled with his Protestant persecution, enabled William of Orange and his party to gain the ascendancy in the Republic and finally lay the groundwork for his long-sought alliance against France.[26]

Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg (1620–88). He was succeeded by his son, Frederick, who proved to be one of William of Orange's most loyal allies.

Although James II had permitted the Huguenots to settle in England, he had enjoyed an amicable relationship with his co-religionist Louis XIV, realising the importance of the friendship for his own Catholicising measures at home against the suspicions of his Protestant majority.[27] But the Huguenot presence gave an immense boost to anti-French discourse, and they joined forces with elements in England already highly suspicious of James.[28] However, conflicts between French and English commercial interests in North America had caused severe friction between the two governments: the French had grown antagonistic towards the Hudson's Bay Company and the New England colonies, while the English looked upon French pretensions in New France as encroaching upon their own possessions. This rivalry had spread to the other side of the world where English and French East India companies had already embarked upon hostilities.[29]

Many in Germany reacted negatively to the persecution of the Huguenots, disabusing the Protestant princes of the idea that Louis XIV was their ally against the intolerant practices of the Catholic Habsburgs.[30] The Elector of Brandenburg answered the revocation of the Edict of Nantes by promulgating the Edict of Potsdam, and invited the fleeing Huguenots to Brandenburg. But there were motivations other than religious adherence that disabused him (and other German Princes) of his allegiance to France. Louis XIV had pretensions in the Palatinate in the name of his sister-in-law, Elizabeth Charlotte, threatening further annexations of the Rhineland.[31] Thus Frederick-William, spurning his French subsidies, ended his alliance with France and reached agreements with William of Orange, the Emperor, and, temporarily putting aside his differences over Pomerania, with King Charles XI of Sweden.[24]

The consequences of the flight of the Huguenots in southern France brought outright war in the Alpine districts of Piedmont in the Duchy of Savoy (a northern Italian state nominally part of the Empire). From their fort at Pinerolo the French were able to exert considerable pressure on the Duke of Savoy and force him to persecute his own Protestant community, the Vaudois (Valdesi). This constant threat of interference and intrusion into his domestic affairs was a source of concern for Victor Amadeus, and from 1687 the Duke's policy became increasingly anti-French as he searched for a chance to assert his aspirations and concerns. This criticism for Louis XIV's regime was spreading all over Europe.[32] The Truce of Ratisbon, followed by the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, was a cause of suspicion as to Louis's true intentions; many were also fearful of the King's supposed designs on universal monarchy – the uniting of the Spanish and German crowns with that of France. In response, representatives from the Emperor, the south German princes, Spain (motivated by the French attack in 1683 and the imposed truce of 1684), and Sweden (in their capacity as princes within the Empire) met in Augsburg to form a defensive league of the Rhine in July 1686. Pope Innocent XI – angered in part at Louis's failure to go on crusade against the Turks – gave secret support.[33]

Prelude: 1687–88

Louvois (1641–1691), Louis XIV's belligerent secretary of state at the height of his powers, by Pierre Mignard.

The League of Augsburg had little military power – the Empire and its Allies in the form of the Holy League were still busy fighting the Ottoman Turks in Hungary.[34] Many of the petty princes were reluctant to act due to the fear of French retaliation. Nevertheless, Louis XIV watched with apprehension Leopold I's advances against the Ottomans. Habsburg victories along the Danube at Buda in September 1686,[35] and Mohács a year later[36] had convinced the French that the Emperor, in alliance with Spain and William of Orange, would soon turn his attention towards France and retake what had recently been won by Louis's military intimidation.[37] In response, Louis XIV sought to guarantee his territorial gains of the Reunions by forcing his German neighbours into converting the Truce of Ratisbon into a permanent settlement. However, a French ultimatum issued in 1687 failed to gain the desired assurances from the Emperor whose victories in the east made the Germans less anxious to compromise in the west.[38]

Max Emanuel (1662–1726) by Joseph Vivien.

Another testing point concerned the pro-French Archbishop-Elector, Maximilian Henry, and the question of his succession in the state of Cologne.[39] The territory of the archbishopric lay along the left bank of the Rhine and included three fortresses of the river-line: Bonn, Rheinberg, and Kaiserswerth, besides Cologne itself. Moreover, the archbishop was also prince-bishop of Liège, the small state astride the strategic highway of the river Meuse. When the Elector died on 3 June 1688 Louis XIV pressed for the pro-French Bishop of Strasbourg, William Egon of Fürstenberg, to succeed him. The Emperor, however, favoured Joseph Clement, the brother of Max Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria.[40] With neither candidate able to secure the necessary two-thirds of the vote of the canons of the cathedral chapter, the matter was referred to Rome. There was no prospect of the Pope, already in deep conflict with Louis, favouring the French candidate, and on 26 August 1688 he awarded the election to Clement.[41]

On 6 September 1688, Leopold I's forces under the Elector of Bavaria secured Belgrade for the Empire.[39] With the Ottomans appearing close to collapse Louis XIV's ministers, Louvois and Colbert de Croissy, felt it essential to have a quick resolution along the German frontier before the Emperor turned from the Balkans to lead a comparatively united German Empire against France on the Rhine and reverse the Ratisbon settlement.[42] On 24 September Louis published his manifesto, his Mémoire de raisons, listing his grievances: he demanded that the Truce of Ratisbon be turned into a permanent resolution, and that Fürstenburg be appointed Archbishop-Elector of Cologne. He also proposed to occupy the territories that he believed belonged to his sister-in-law regarding the Palatinate succession. The Emperor and the German princes, the Pope, and William of Orange were quite unwilling to grant these demands. For the Dutch in particular, Louis's control of Cologne and Liège would be strategically unacceptable, for with these territories in French hands the Spanish Netherlands 'buffer-zone' would be effectively bypassed. The day after Louis issued his manifesto – well before his enemies could have known its details – the main French army crossed the Rhine as a prelude to investing Philippsburg, the key post between Luxembourg (annexed in 1684) and Strasbourg (seized in 1681), and other Rhineland towns.[43] This pre-emptive strike was intended to intimidate the German states into accepting his conditions, while encouraging the Ottoman Turks to continue their own struggle with the Emperor in the east.[44]

Louis XIV and his ministers had hoped for a quick resolution similar to that secured from the War of the Reunions, but by 1688 the situation was drastically different. In the east an Imperial army, now manned with veteran officers and men, had dispelled the Turkish threat and crushed Imre Thököly's revolt in Hungary; while in the west and north, William of Orange was fast becoming the leader of a coalition of Protestant states, anxious to join with the Emperor and Spain, and end the hegemony of France.[23] Louis wanted a short defensive war, yet by crossing the Rhine that summer he began a long war of attrition; a war framed by interests of the state, its defensible frontiers, and the balance of power in Europe.[45]

Nine years of war: 1689–97

Rhineland and the Empire

Rhine campaign 1688–89. French forces cross the Rhine at Strasbourg and proceed to invest Philippsburg – the key to the middle Rhine – on 27 September 1688.

Marshal Duras, Vauban, and 30,000 men – all under the nominal command of the Dauphin – besieged the Elector of Trier's fortress of Philippsburg on 27 September 1688; after a vigorous defence it fell on 30 October.[46] Louis XIV's army proceeded to take Mannheim, which capitulated on 11 November, shortly followed by Frankenthal. Other towns fell without resistance, including Oppenheim, Worms, Bingen, Kaiserslautern, Heidelberg, Speyer and, above all, the key fortress of Mainz. After Coblenz failed to surrender Boufflers put it under heavy bombardment, but it did not fall to the French.[46]

Louis XIV now mastered the Rhine south of Mainz to the Swiss border, but although the attacks kept the Turks fighting in the east, the impact on Leopold I and the German states had the opposite effect of what had been intended.[47] The League of Augsburg was not strong enough to meet the threat, but on 22 October the powerful German princes, including the Elector of Brandenburg, John George III, Elector of Saxony, Ernest Augustus of Hanover, and Charles I, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, reached an agreement in Magdeburg that mobilised the forces of north Germany. Meanwhile, the Emperor recalled the Bavarian, Swabian, and Franconian troops under the Elector of Bavaria from the Ottoman front to defend south Germany. The French had not prepared for such an eventuality. Realising that the war in Germany was not going to end quickly and that the Rhineland blitz would not be a brief and decisive parade of French glory, Louis XIV and Louvois resolved upon a scorched-earth policy in the Palatinate, Baden and Württemberg, intent on denying enemy troops local resources and prevent them from invading French territory.[48] By 20 December 1688 Louvois had selected all the cities, towns, villages and châteaux intended for destruction. On 2 March 1689 Count of Tessé torched Heidelberg; on 8 March Montclar levelled Mannheim. Oppenheim and Worms were finally destroyed on 31 May, followed by Speyer on 1 June, and Bingen on 4 June. In all, French troops burnt over 20 substantial towns as well as numerous villages.[49]

The Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire declared war on France on 11 February 1689, beginning a unified imperial war effort.[50] The Germans prepared to take back what they had lost, and in 1689 formed three armies along the Rhine. The smallest of these, initially under the Elector of Bavaria, protected the upper Rhine between the lines north of Strasbourg to the Black Forest. On the middle Rhine stood the largest army under the best Imperial general, and commander-in-chief, Charles V, Duke of Lorraine. Charles V cleared away the French threat on Frankfurt and opened trenches around Mainz on 22/23 July. After a bloody two months siege the Marquis of Huxelles finally yielded the town on 8 September.[51] Meanwhile, on the lower Rhine stood the Elector of Brandenburg who, aided by the celebrated Dutch engineer Menno van Coehoorn, besieged Kaiserswerth. Kaiserswerth fell on 26 June before the Elector led his army on Bonn, which, having endured a heavy bombardment, finally capitulated on 10 October.[52] The invasion of the Rhineland had united the German princes in their opposition to Louis XIV who had lost more than he had gained that year along the Rhine. The campaign had also created a diversion of French forces and sufficient time for William of Orange to invade England.[48]

Britain

James II's ill-advised attempts to Catholicise the army, government and other institutions had proved increasingly unpopular with his mainly Protestant subjects. His open Catholicism and his dealings with Catholic France had also strained relations between England and the Dutch Republic, but because his daughter Mary was the Protestant heir to the English throne, her husband William of Orange had been reluctant to act against James II for fear it would ruin her succession prospects.[53] Yet if England was left to itself the situation could become desperate for the Dutch Republic: Louis XIV might intervene and so make James II his vassal;[citation needed] or James, wishing to distract his subjects, might even join with Louis in a repetition of the attack made on the Dutch Republic in 1672. By the end of 1687, therefore, William had envisaged intervention, and by early 1688 he had secretly begun to make active preparations.[54] The birth of a son to James's second wife in June 1688 displaced William's wife Mary as James's heir apparent. With the French busy creating their cordon sanitaire in the Palatinate (too busy to consider serious intervention in the Spanish Netherlands or to move against the south-eastern Dutch provinces along the Rhine) the States General unanimously gave William their full support in the knowledge that the overthrow of James II was in the security interests of their own state.[55]

Louis XIV had considered William's invasion as a declaration of war between France and the Dutch Republic (officially declared on 26 November); but he did little to stop the invasion – his main concern was the Rhineland. Moreover, French diplomats had calculated that William's action would plunge England into a protracted civil war that would either absorb Dutch resources or draw England closer to France. However, after landing his forces unhindered at Torbay on 5 November (O.S) 1688, many welcomed William with open arms, and the subsequent Glorious Revolution brought a rapid end to James II's reign.[56] On 13 February 1689 (O.S.) William of Orange became King William III of England – reigning jointly with his wife Mary – and bound together the fortunes of England and the Dutch Republic. Yet few people in England suspected that William had sought the crown for himself or that his aim was to bring England into the war against France on the Dutch side. The Convention Parliament did not see that the offer of joint monarchy carried with it the corollary of a declaration of war, but the subsequent actions of the deposed king finally swung Parliament behind William's war policy.[57]

British historian J.R. Jones states that King William was given:

- supreme command within the alliance throughout the Nine Years war. His experience and knowledge of European affairs made him the indispensable director of Allied diplomatic and military strategy, and he derived additional authority from his enhanced status as king of England – even the Emperor Leopold...recognized his leadership. William's English subjects played subordinate or even minor roles in diplomatic and military affairs, having a major share only in the direction of the war at sea. Parliament and the nation had to provide money, men and ships, and William had found it expedient to explain his intentions...but this did not mean that Parliament or even ministers assisted in the formulation of policy.[58]

Ireland

Irish campaign 1689–1691. The majority of Irish people supported James II due to his 1687 Declaration of Indulgence, granting religious freedom to all denominations in England and Scotland. James II also promised the Irish Parliament the eventual right to self-determination.[59][60]

James II had fled to France to the welcoming arms of Louis XIV. In March 1689 (supported by French gold, troops, and generals) he sailed from his exile at St Germain to rally Catholic support in Ireland as a first step to regaining his thrones. The French King supported James for two reasons: first, Louis XIV fervently believed in his God-ordained right to the throne; and second, he wished to divert William III's forces away from the Low Countries.[61] James II's initial aim, and that of his deputy the Duke of Tyrconnell, was to pacify the northern Protestant strongholds. However, his ill-equipped army of around 40,000 could do little more than besiege Derry. Derry mounted a determined defence that lasted 105 days, and the city was finally relieved by the Royal Navy at the end of July. In the meantime the first major naval engagement of the war was fought off Bantry Bay on 11 May (O.S.) – before England's declaration of war – resulting in a minor French success for Châteaurenault, who managed to land supplies for James II's campaign.[61] For their part, Williamite forces were supplied from the north, and in August the Duke of Schomberg arrived with 15,000 Danish, Dutch, Huguenot, and English reinforcements. However, after taking Carrickfergus his army stalled at Dundalk, suffering through the winter months from sickness and desertion.[62]

On 30 June 1690 (O.S.) the French navy secured victory off Beachy Head in the English Channel where Admiral Tourville defeated Admiral Torrington's inferior Anglo-Dutch fleet.[63] However, Louis XIV's decision not to use his main fleet as a subsidiary to the Irish campaign had enabled William III to land in Ireland with a further 15,000 men earlier that month.[63] With these reinforcements William III secured decisive victory at the Battle of the Boyne on 1 July (O.S.), and once again forced James II to flee back to France.[64] Following the Earl of Marlborough's capture of the southern ports of Cork and Kinsale in October 1690,[64] – thereby confining French and Jacobite troops to the west of the country – William III now felt confident enough to return to the Continent at the beginning of 1691 to command the coalition army in the Low Countries, leaving Baron van Ginkell to lead his troops in Ireland. After Ginkell's victory over the Marquis of Saint-Ruth at the Battle of Aughrim on 12 July (O.S.), the remaining Jacobite strongholds fell in rapid succession. Without prospect of further French assistance the capitulation at Limerick finally sealed victory for William III and his supporters in Ireland with the signing of the Treaty of Limerick on 3 October (O.S.). English troops could now return to the Low Countries in strength.[65]

War aims and the Grand Alliance

James II (1633–1701) c. 1690, artist unknown

The success of William's invasion of England rapidly led to the coalition he had long desired. On 12 May 1689 the Dutch and the Holy Roman Emperor had signed an offensive compact in Vienna, the aims of which were no less than to force France back to her borders as they were at the end of the Franco-Spanish War (1659), thus depriving Louis XIV of all his gains since his assumption of power.[66] This meant for the Emperor and the German princes the reconquest of Lorraine, Strasbourg, parts of Alsace, and some Rhineland fortresses. Leopold I had tried to disentangle himself from the Turkish war to concentrate on the coming struggle, but the French invasion of the Rhineland had encouraged the Turks to stiffen their terms for peace and make demands the Emperor could not conceivably accept.[67] Leopold I's decision to side with the coalition (against the opposition of many of his advisers) was, therefore, a decision to intervene in the west while continuing to fight the Ottomans in the Balkans. Although the Emperor's immediate concerns were for the Rhineland, the most important parts of the treaty were the secret articles pledging England and the States-General to assist him in securing the Spanish succession should Charles II die without an heir, and to use their influence to secure his son's election to succeed him as Emperor.

Marshal Vauban (1633–1707), Louis XIV's greatest military engineer and one of his most trusted advisers

William III regarded the war as an opportunity to reduce the power of France and protect the Dutch Republic, while providing conditions that would encourage trade and commerce.[68] Although there remained territorial anomalies, Dutch war aims did not involve substantial alterations to the frontier; but William did aim to secure his new position in Britain. By seeking refuge in France and subsequently invading Ireland, James II had given William III the ideal instrument to convince the English parliament that entry into a major European war was unavoidable. With the support of Parliament, William III and Mary II declared war on 17 May 1689 (O.S.); they then passed the Trade with France Act 1688 (1 Will. & Mar. c. 34), which prohibited all English trade and commerce with France, effective 24 August 1689.[69] This Anglo-Dutch alignment was the basis for the Grand Alliance, ratified on 20 December by William III representing England, Anthonie Heinsius and Treasurer Jacob Hop representing the Dutch Republic, and Königsegg and Stratman representing Emperor Leopold I. Like the Dutch the English were not preoccupied with territorial gains on the Continent, but were deeply concerned with limiting the power of France to defend against a Jacobite restoration (Louis XIV threatened to overthrow the Glorious Revolution and the precarious political settlement by supporting the old king over the new one).[70] William III had secured his goal of mobilising Britain's resources for the anti-French coalition, but the Jacobite threat in Scotland and Ireland meant only a small English expeditionary force could be committed to assist the Dutch States Army in the coalition in the Spanish Netherlands for the first three years of the war.

The Duke of Lorraine also joined the Alliance at the same time as England, while the King of Spain (who had been at war with France since April 1689) and the Duke of Savoy signed in June 1690. The Allies had offered Victor Amadeus handsome terms to join the Grand Alliance, including the return of Casale to Mantua (he hoped it would revert to him upon the death of the childless Duke of Mantua) and of Pinerolo to himself. His adhesion to the Allied cause would facilitate the invasion of France through Dauphiné and Provence, where the naval base of Toulon lay.[71] In contrast Louis XIV had embarked on a policy of overt military intimidation to retain Savoy in the French orbit, and had envisaged the military occupation of parts of Piedmont (including the citadel of Turin) to guarantee communications between Pinerolo and Casale.[72] French demands on Victor Amadeus, and their determination to prevent the Duke from achieving his dynastic aims,[73] were nothing less than an attack on Savoyard independence, convincing the Duke that he had to stand up to French aggression.[72]

The Elector of Bavaria consented to add his name to the Grand Alliance on 4 May 1690, while the Elector of Brandenburg joined the anti-French coalition on 6 September.[74] However, few of the minor powers were as devoted to the common cause, and all protected their own interests; some never hesitated to exact a high price for continuing their support.[75]Charles XI of Sweden supplied the contingents due from his German possessions to the Allied cause (6,000 men and 12 warships),[76] while in August 1689 Christian V of Denmark agreed to a treaty to supply William III with 7,000 troops in return for a subsidy.[74] However, in March 1691 Sweden and Denmark put aside their mutual distrust and made a treaty of armed neutrality for the protection of their commerce and to prevent the war spreading north. To the annoyance of the Maritime Powers the Swedes now saw their rôle outside the great power-struggle of the Nine Years' War, exploiting opportunities to increase their own maritime trade.[77] Nevertheless, Louis XIV at last faced a powerful coalition aimed at forcing France to recognise Europe's rights and interests.[66]

Expanding war: 1690–91

The Low Countries c. 1700: the principal theatre during the Nine Years' War

The main fighting of the Nine Years' War took place around France's borders: in the Spanish Netherlands; the Rhineland; Catalonia; and Piedmont-Savoy. The importance of the Spanish Netherlands was the result of its geographic position, sandwiched between France and the Dutch Republic. Initially Marshal Humières commanded French forces in this theatre but in 1689, while the French concentrated on the Rhine, it produced little more than a stand-off – the most significant engagement occurred when William's second-in-command, the Prince of Waldeck, defeated Humières in a skirmish at the Battle of Walcourt on 25 August. However, by 1690 the Spanish Netherlands had become the main seat of the war where the French formed two armies: Boufflers' army on the Moselle, and a larger force to the west under Humières' successor – and Louis XIV's greatest general of the period – Marshal Luxembourg. On 1 July Luxembourg secured a clear tactical victory over Waldeck at the Battle of Fleurus; but his success produced little benefit – Louis XIV's concerns for the dauphin on the Rhine (where Marshal de Lorge now held actual command) overrode strategic necessity in the other theatres and forestalled a plan to besiege Namur or Charleroi.[72] For the Emperor and the German princes, though, the most serious fact of 1690 was that the Turks had been victorious on the Danube, requiring them to send reinforcements to the east. The Elector of Bavaria – now Imperial commander-in-chief following Lorraine's death in April – could offer nothing on the lower or upper Rhine, and the campaign failed to produce a single major battle or siege.[78]

Battle of Fleurus, 1690

The smallest front of the war was in Catalonia. In 1689 the Duke of Noailles had led French forces there aimed at bringing further pressure to bear on the Spanish by re-igniting a peasant rising against Charles II, which initially broke out in 1687. Exploiting the situation, Noailles captured Camprodon on 22 May, but a larger Spanish army under the Duke of Villahermosa forced him to withdraw back to Roussillon in August.[79] The Catalan campaign settled down in 1690, but a new front in Piedmont-Savoy proved more eventful. A ferment of religious animosities and Savoyard hatred of the French produced a theatre characterised by massacres and atrocities: constant guerrilla attacks by the armed populace were met by draconian reprisals.[80] In 1690 Saint-Ruth took most of the Victor Amadeus II's exposed Duchy of Savoy, routing the Savoyard army in the process until only the great fortress of Montmélian remained in ducal hands; while to the south in Piedmont, Nicolas Catinat led 12,000 men and soundly defeated Victor Amadeus at the Battle of Staffarda on 18 August. Catinat immediately took Saluzzo, followed by Savigliano, Fossano, and Susa, but lacking sufficient troops, and with sickness rife within his army, Catinat was obliged to withdraw back across the Alps for the winter.[81]

Siege of Mons 1691. While he never commanded a battle in the open field, Louis XIV attended many sieges (at a safe distance) until advancing age limited his activities.

French successes in 1690 had checked the Allies on most of the mainland fronts, yet their victories had not broken the Grand Alliance. With the hope of unhinging the coalition French commanders in 1691 prepared for an early double-blow: the capture of Mons in the Spanish Netherlands, and Nice in northern Italy. Boufflers invested Mons on 15 March with some 46,000 men, while Luxembourg commanded a similar force of observation. After some of the most intense fighting of all of Louis XIV's wars the town inevitably capitulated on 8 April.[82] Luxembourg proceeded to take Halle at the end of May, while Boufflers bombarded Liège; but these acts proved to have no political nor strategic consequence.[83] The final action of note in the Low Countries came on 19 September when Luxembourg's cavalry surprised and defeated the rear of the Allied forces in a minor action near Leuze. Now that the defence of the Spanish Netherlands depended almost wholly on the Allies William III insisted on replacing its Spanish governor, the Marquis of Gastañaga, with the Elector of Bavaria, thus overcoming delays in getting decisions from Madrid.[84]

North Italian campaign 1690–96. The territories of Victor Amadeus II, the Duke of Savoy, comprised the County of Nice, Duchy of Savoy and the Principality of Piedmont, which contained the capital city, Turin.

In 1691 there was little significant fighting in the Catalan and Rhineland fronts. In contrast, the northern Italian theatre was very active. Villefranche fell to French forces on 20 March, followed by Nice on 1 April, forestalling any chance of an Allied invasion of France along the coast. Meanwhile, to the north, in the Duchy of Savoy, the Marquis of La Hoguette took Montmélian (the region's last remaining stronghold) on 22 December – a major loss for the Grand Alliance. However, by comparison the French campaign on the Piedmontese plain was far from successful. Although Carmagnola fell in June, the Marquis of Feuquières, on learning of the approach of Prince Eugene of Savoy's relief force, precipitously abandoned the Siege of Cuneo with the loss of some 800 men and all his heavy guns. With Louis XIV concentrating his resources in Alsace and the Low Countries, Catinat was forced onto the defensive. The initiative in northern Italy now passed to the Allies who, as early as August, had 45,000 men (on paper) in the region, enabling them to regain Carmagnola in October. Louis XIV offered peace terms in December, but anticipating military superiority for the following campaign Amadeus was not prepared to negotiate seriously.[72]

Heavy fighting: 1692–93

After the sudden death of the influential Louvois in July 1691 Louis XIV had assumed a more active role in the direction of military policy, relying on advice from experts such as the Marquis of Chamlay and Vauban.[85] Louvois' death also brought changes to state policy with the less adventurous Duke of Beauvilliers and the Marquis of Pomponne entering Louis XIV's government as ministers of state. From 1691 onwards Louis XIV and Pomponne pursued efforts to unglue the Grand Alliance, including secret talks with Emperor Leopold I and, from August, attempts of religious solidarity with Catholic Spain. The approaches made to Spain came to naught (the Nine Years' War was not a religious war), but the Maritime Powers were also keen for peace. Talks were hampered, however, by Louis XIV's reluctance to cede his earlier gains (at least those made in the Reunions) and, in his deference to the principle of the divine right of kings, his unwillingness to recognise William III's claim to the English throne. For his part William III was intensely suspicious of Louis XIV and his supposed designs for universal monarchy.[86]

Over the winter of 1691–92 the French devised a grand plan to gain the ascendancy over their enemies – a design for the invasion of England in one more effort to support James II in his attempts to regain his kingdoms; and a simultaneous assault on Namur in the Spanish Netherlands. The French hoped that Namur's seizure might inspire the Dutch to make peace, but if not, its capture would nevertheless be an important pawn at any future negotiations.[87] With 60,000 men (protected by a similar force of observation under Luxembourg), Marshal Vauban invested the stronghold on 29 May. The town soon fell but the citadel – defended by van Coehoorn – held out until 30 June. Endeavouring to restore the situation in the Spanish Netherlands William III surprised Luxembourg's army near the village of Steenkirk on 3 August. The Allies enjoyed some initial success, but as French reinforcements came up William III's advance stalled. The Allies retired from the field in good order, and both sides claimed victory: the French because they repulsed the assault; the Allies because they had saved Liège from the same fate as Namur. However, due to the nature of late 17th-century warfare the battle, like Fleurus before it, produced little of consequence.[88] (See below).

Battle of La Hogue, (1692) by Adriaen van Diest. The last act of the battle – French ships set on fire at La Hogue.

While French arms had proved successful at Namur the proposed descent on England was a failure. James II believed that there would be considerable support for his cause once he had established himself on English soil, but a series of delays and conflicting orders ensured a very uneven naval contest in the English Channel.[87] The engagement was fought at the tip of the Cherbourg peninsula, and lasted six days. At the action off Cape Barfleur on 29 May, the French fleet of 44 rated vessels under Admiral Tourville put up stern resistance against Admirals Rooke's and Russell's 82 rated English and Dutch vessels.[89] Nevertheless, the French were forced to disengage: some escaped, but the 15 ships that had sought safety in Cherbourg and La Hogue were destroyed by English seamen and fireships on 2–3 June.[90] With the Allies now dominant in the English Channel James II's invasion was abandoned. Yet the battle itself was not the death-blow for the French navy: the subsequent mismanagement and underfunding of the fleet under Pontchartrain, coupled with Louis XIV's own personal lack of interest, were central to the French losing naval superiority over the English and Dutch during the Nine Years' War.[91]

Meanwhile, in southern Europe the Duke of Savoy with 29,000 men (substantially exceeding Catinat's number who had sent some troops to the Netherlands) invaded Dauphiné via the mountain trails shown to them by the Vaudois. The Allies invested Embrun, which capitulated on 15 August, before sacking the deserted town of Gap.[92] However, with their commander falling ill with smallpox, and concluding that holding Embrun was untenable, the Allies abandoned Dauphiné in mid-September, leaving behind seventy villages and châteaux burned and pillaged.[93] The attack on Dauphiné had required Noailles give up troops to bolster Catinat, condemning him to a passive campaign in Catalonia; but on the Rhine the French gained the upper hand. De Lorge devoted much of his effort imposing contributions on German lands, spreading terror far and wide in Swabia and Franconia.[92] In October the French commander relieved the siege of Ebernburg on the left bank of the Rhine before returning to winter quarters.[88]

By 1693 the French army had reached an official size of over 400,000 men (on paper), but Louis XIV was facing an economic crisis.[94] France and northern Italy witnessed severe harvest failures resulting in widespread famine which, by the end of 1694, had accounted for the deaths of an estimated two million people.[95] Nevertheless, as a prelude to offering generous peace terms before the Grand Alliance Louis XIV planned to go over to the offensive: Luxembourg would campaign in Flanders, Catinat in northern Italy, and in Germany, where Louis XIV had hoped for a war-winning advantage, Marshal de Lorge would attack Heidelberg. In the event, Heidelberg fell on 22 May before Luxembourg's army took to the field in the Netherlands, but the new Imperial commander on the Rhine, Prince Louis of Baden, provided a strong defence and prevented further French gains. Luxembourg had better luck in the Low Countries, however. After taking Huy on 23 July, the French commander outmanoeuvred William III, catching him off-guard between the villages of Neerwinden and Landen. The ensuing engagement on 29 July was a close and costly encounter but French forces, whose cavalry once again showed their superiority, prevailed.[96] Luxembourg and Vauban proceeded to take Charleroi on 10 October which, together with the earlier prizes of Mons, Namur and Huy, provided the French with a new and impressive forward line of defence.[97]

Catalan campaign 1689–97. The Catalan front was the smallest of the Nine Years' War.

In northern Italy, meanwhile, Catinat marched on Rivoli (with reinforcements from the Rhine and Catalan fronts), forcing the Duke of Savoy to abandon the siege and bombardment of Pinerolo (25 September – 1 October) before withdrawing to protect his rear. The resultant Battle of Marsaglia on 4 October 1693 ended in a resounding French victory. Turin now lay open to attack but further manpower and supply difficulties prevented Catinat from exploiting his gain, and all the French could get out of their victory was renewed breathing-space to restock what was left of Pinerolo.[72] Elsewhere, Noailles secured the valuable seaport of Rosas in Catalonia on 9 June before withdrawing into Roussillon. When his opponent, Medina-Sidonia, abandoned plans to besiege Bellver, both sides entered winter quarters.[98] Meanwhile, the French navy achieved victory in its final fleet action of the war. On 27 June Tourville's combined Brest and Toulon squadrons ambushed the Smyrna convoy (a fleet of between 200–400 Allied merchant vessels travelling under escort to the Mediterranean) as it rounded Cape St. Vincent. The Allies lost approximately 90 merchant ships with a value of some 30 million livres.[99]

War and diplomacy: 1694–95

French arms at Heidelberg, Rosas, Huy, Landen, Charleroi and Marsaglia had achieved considerable battlefield success, but with the severe hardships of 1693 continuing through to the summer of 1694 France was unable to expend the same level of energy and finance for the forthcoming campaign. The crisis reshaped French strategy, forcing commanders to redraft plans to fit the dictates of fiscal shortfalls.[100] In the background, Louis XIV's agents were working hard diplomatically to unhinge the coalition but the Emperor, who had secured with the Allies his 'rights' to the Spanish succession should Charles II die during the conflict, did not desire a peace that would not prove personally advantageous. The Grand Alliance would not come apart as long as there was money available and a belief that the growing strength of their armies would soon be much greater than those of France.[101]

Bombardment of Dieppe, 1694

In the Spanish Netherlands Luxembourg still had 100,000 men; but he was outnumbered.[102] Lacking sufficient supplies to mount an attack Luxembourg was unable to prevent the Allies garrisoning Dixmude and, on 27 September 1694, recapturing Huy, an essential preliminary to future operations against Namur.[103] Elsewhere, de Lorge marched and manoeuvred against Baden on the Rhine with undramatic results before the campaign petered out in October; while in Italy, the continuing problems with French finance and a complete breakdown in the supply chain prevented Catinat's push into Piedmont.[72] However, in Catalonia the fighting proved more eventful. On 27 May Marshal Noailles, supported by French warships, soundly defeated the Marquis of Escalona's Spanish forces at the Battle of Torroella on the banks of the river Ter; the French proceeded to take Palamós on 10 June, Gerona on 29 June, and Hostalric, opening the route to Barcelona. With the Spanish King threatening to make a separate peace with France unless the Allies came to his assistance, William III prepared the Anglo-Dutch fleet for action. Part of the fleet under Admiral Berkeley would remain in the north, first leading the disastrous amphibious assault on Brest on 18 June, before bombarding French coastal defences at Dieppe, Saint-Malo, Le Havre, and Calais. The remainder of the fleet under Admiral Russell was ordered to the Mediterranean, linking up with Spanish vessels off Cadiz. The Allied naval presence compelled the French fleet back to the safety of Toulon, which, in turn, forced Noailles to withdraw to the line of the Ter, harassed en route by General Trinxería's miquelets.[104] By shielding Barcelona in this way the Allies kept Spain in the war for two more years.[105]

Siege of Namur (1695) by Jan van Huchtenburg. In the foreground William III, dressed in grey, confers with the Elector of Bavaria.

In 1695 French arms suffered two major setbacks: first was the death on 5 January of Louis XIV's greatest general of the period, Marshal Luxembourg (to be succeeded by the Duke of Villeroi); the second was the loss of Namur. In a role reversal of 1692 Coehoorn conducted the siege of the stronghold under William III, and the Electors of Bavaria and Brandenburg. The French had attempted diversions with the bombardment of Brussels, but despite Boufflers' stout defence Namur finally fell on 5 September.[106] The siege had cost the Allies a great deal in men and resources, and had pinned down William III's army through the whole summer campaign; but the recapture of Namur, together with the earlier prize of Huy, had restored the Allied position on the Meuse, and had secured communications between their armies in the Spanish Netherlands and those on the Moselle and Rhine.[107]

Meanwhile, the recent fiscal crisis had brought about a transformation in French naval strategy – the Maritime Powers now outstripped France in shipbuilding and arming, and increasingly enjoyed a numerical advantage.[108] Suggesting the abandonment of fleet warfare, guerre d'escadre, in favour of commerce-raiding, guerre de course, Vauban advocated the use of the fleet backed by individual shipowners fitting out their own vessels as privateers, aimed at destroying the trade of the Maritime Powers. Vauban argued that this strategic change would deprive the enemy of its economic base without costing Louis XIV money that was far more urgently needed to maintain France's armies on land. Privateers cruising either as individuals or in complete squadrons from Dunkirk, St Malo and the smaller ports, achieved significant success. For example, in 1695, the Marquis of Nesmond, with seven ships of the line, captured vessels from the English East India Company that were said to have yielded 10 million livres. In May 1696, Jean Bart slipped the blockade of Dunkirk and struck a Dutch convoy in the North Sea, burning 45 of its ships; on 18 June 1696 he won the battle at Dogger Bank; and in May 1697, the Baron of Pointis with another privateer squadron attacked and seized Cartagena, earning him, and the king, a share of 10 million livres.[109]

Duke of Noailles (1650–1708). Due to illness Vendôme replaced Noailles as French commander in Catalonia in 1695.

For their part, the Allied navy expended more shells on St Malo, Granville, Calais, and Dunkirk; likewise on Palamos in Catalonia where Charles II had appointed the Marquis of Gastañaga as the governor-general. The Allies sent Austrian and German reinforcements under Prince George of Hesse-Darmstadt, a cousin of the Queen of Spain, while the French replaced the ailing Noailles with the Duke of Vendôme who would become one of Louis XIV's best generals. But the balance of military power was turning dangerously against the French. In Spain, in the Rhineland, and in the Low Countries, Louis XIV's forces only barely held their own: the bombardment of the French channel ports, the threats of invasion, and the loss of Namur were causes of great anxiety for the King at Versailles.[110]

In the meantime the diplomatic breakthrough was made in Italy. For two years the Duke of Savoy's Minister of Finance, Gropello, and the Count of Tessé (Catinat's second-in-command), had secretly been negotiating a bi-lateral agreement to end the war in Italy. Central to the discussions were the two French fortresses that flanked the Duke's territory – Pinerolo and Casale, the latter now completely cut off from French assistance.[72] By now Victor Amadeus had come to fear the growth of Imperial military power and political influence in the region (now more than he feared the French) and the threat it posed to Savoyard independence. Knowing, therefore, that the Imperials were planning to besiege Casale the Duke proposed that the French garrison surrender to him following a token show of force, after which the fortifications would be dismantled and handed back to the Duke of Mantua.[111] Louis XIV was compelled to accept, and after a sham siege and nominal resistance Casale surrendered to Amadeus on 9 July 1695; by mid-September the place had been razed.

Road to Ryswick: 1696–97

Most fronts were relatively quiet throughout 1696: the armies in Flanders, along the Rhine, and in Catalonia, marched and counter-marched but little was achieved. Louis XIV's hesitancy to engage with the Allies (despite the confidence of his generals) may have reflected his knowledge of the secret talks that had begun more than a year earlier—with François de Callières acting for Louis XIV, and Jacob Boreel and Everhard van Weede Dijkvelt representing the Dutch.[112] By the spring of 1696 the talks covered the whole panorama of problems that were proving an obstacle to peace. The most difficult of these were the recognition of the Prince of Orange as the King of England and the subsequent status of James II in France; the Dutch demand for a barrier against future French aggression; French tariffs on Dutch commerce; and the territorial settlements in the Rhine–Moselle areas regarding the Reunions and the recent conquests, particularly the strategically important city of Strasbourg.[112] Louis XIV had succeeded in establishing the principle that a new treaty would be fixed within the framework of the Treaties of Westphalia and Nijmegen, and the Truce of Ratisbon, but with the Emperor's demands for Strasbourg, and William III's insistence that he be recognized as King of England before the conclusion of hostilities, it hardly seemed worthwhile in calling for a peace conference.[113]

In Italy the secret negotiations were proving more productive, with the French possession of Pinerolo now central to the talks. When Amadeus threatened to besiege Pinerolo the French, concluding that its defence was not now possible, agreed to hand back the stronghold on condition that its fortifications were demolished. The terms were formalised as the Treaty of Turin on 29 August 1696, by which provision Louis XIV also returned, intact, Montmélian, Nice, Villefranche, Susa, and other small towns.[114] Amongst other concessions Louis XIV also promised not to interfere in Savoy's religious policy regarding the Vaudois, provided the Duke prevents any communication between them and French Huguenots. In return, Amadeus agreed to abandon the Grand Alliance and join with Louis XIV – if necessary – to secure the neutralisation of northern Italy. The Emperor, diplomatically outmanoeuvred, was compelled to accept peace in the region by signing the Treaty of Vigevano of 7 October, to which the French immediately acceded. Italy was neutralised and the Nine Years' War in the peninsula came to an end. Savoy had emerged as an independent sovereign House and a key second-rank power: the Alps, rather than the River Po, would be the boundary of France in the south-east.[72]

The Treaty of Turin started a scramble for peace. With the continual disruption of trade and commerce politicians from England and the Dutch Republic were desirous for an end to the war. France was also facing economic exhaustion, but above all Louis XIV was becoming convinced that Charles II of Spain was near death and he knew that the break-up of the coalition would be essential if France was to benefit from the dynastic battle ahead.[115] The contending parties agreed to meet at Ryswick (Rijswijk) and come to a negotiated settlement. But as talks continued through 1697, so did the fighting. The main French goal that year in the Spanish Netherlands was Ath. Vauban and Catinat (now with troops freed from the Italian font) invested the town on 15 May while Marshals Boufflers and Villeroi covered the siege; after an assault on 5 June the Count of Roeux surrendered and the garrison marched out two days later. The Rhineland theatre in 1697 was again quiet: the French commander, Marshal Choiseul (who had replaced the sick de Lorge the previous year), was content to remain behind his fortified lines. Although Baden took Ebernberg on 27 September, news of the peace brought an end to the desultory campaign, and both armies drew back from one another. In Catalonia, however, French forces (now also reinforced with troops from Italy) achieved considerable success when Vendôme, commanding some 32,000 troops, besieged and captured Barcelona.[116] The garrison, under Prince George of Hesse-Darmstadt, capitulated on 10 August. Yet it had been a hard-fought contest: French casualties amounted to about 9,000, and the Spanish had suffered some 12,000 killed, wounded or lost.[117]

North American theatre (King William's War)

19th-century print showing Quebec batteries firing on William Phips' squadron during October 1690.

The European war was reflected in North America, where it was known as King William's War, though the North American contest was very different in meaning and scale. The European war declaration arrived amid long-running tensions over control of the fur trade, economically vital to both French and English colonies, and influence over the Iroquois, who controlled much of that trade.[118] The French were determined to hold the St. Lawrence country and to extend their power over the vast basin of the Mississippi.[119] Moreover, Hudson Bay was a focal point of dispute between the Protestant English and Catholic French colonists, both of whom claimed a share of its occupation and trade. Although important to the colonists, the North American theatre of the Nine Years' War was of secondary importance to European statesmen. Despite numerical superiority, the English colonists suffered repeated defeats as New France effectively organised its French troops, local militia and Indian allies (notably the Algonquins and Abenakis), to attack frontier settlements.[120] Almost all resources sent to the colonies by England were to defend the English West Indies, the crown jewels of the empire.

Friction over Indian relations worsened in 1688 with French incursions against the Iroquois in upstate New York, and with Indian raids against smaller settlements in Maine.[121] The Governor General of New France, Louis de Buade de Frontenac, capitalising on disorganisation in New York and New England following the collapse of the Dominion of New England,[122] expanded the war with a series of raids on the northern borders of the English settlements: first was the destruction of Dover, New Hampshire, in July 1689; followed by Pemaquid, Maine, in August.[123] In February 1690 Schenectady in New York was attacked; massacres at Salmon Falls and Casco Bay followed. In response, on 1 May 1690 at the Albany Conference, colonial representatives elected to invade Canada. In August a land force commanded by Colonel Winthrop set off for Montreal, while a naval force, commanded by the future governor of Massachusetts, Sir William Phips (who earlier on 11 May had seized the capital of French Acadia, Port Royal), set sail for Quebec via the Saint Lawrence River. They were repulsed in Battle of Quebec and the expedition on the St Lawrence failed, while the French retook Port Royal.[120]

The war dragged on for several years longer in a series of desultory sallies and frontier massacres: neither the leaders in England nor France thought of weakening their position in Europe for the sake of a knock-out blow in North America.[124] By the terms of the Treaty of Ryswick, the boundaries and outposts of New France, New England, and New York remained substantially unchanged. In Newfoundland and Hudson's Bay French influence now predominated but William III, who had made the interests of the Bay Company a cause of war in North America, was not prepared to hazard his European policy for the sake of their pursuit. The Iroquois Five Nations, abandoned by their English allies, were obliged to open separate negotiations, and by the treaty of 1701 they agreed to remain neutral in any future Anglo-French war.[125]

Asia and the Caribbean

The Battle of Lagos June 1693; French victory and the capture of the Smyrna convoy was the most significant English mercantile loss of the war.

When news of the European war reached Asia, English, French and Dutch colonial governors and merchants quickly took up the struggle. In October 1690 the French Admiral Abraham Duquesne-Guitton sailed into Madras to bombard the Anglo-Dutch fleet; this attack proved foolhardy but extended the war into the Far East.[126] In 1693 the Dutch launched an expedition against their French commercial rivals at Pondichéry on the south-eastern coast of India; the small garrison under François Martin was overwhelmed and surrendered on 6 September.[127]

The Caribbean and the Americas were historically an area of conflict between England and Spain but the two were now Allies while outside North America French interests were far less significant. Saint Kitts twice changed hands and there was sporadic conflict in Jamaica, Martinique and Hispaniola but mutual suspicion between the English and Spanish limited joint operations. The Allies had the naval advantage in these isolated areas, though it proved impossible to keep the French from supplying their colonial forces.[128]

By 1693, it was clear the campaigns in Flanders had not dealt a decisive blow to either the Dutch Republic or England and so the French switched to attacking their trade. The Battle of Lagos in 1693 and the loss of the Smyrna convoy caused intense anger among English merchants who demanded increased global protection from the navy. In 1696, a combination of regular French naval forces and privateers went to the Caribbean hoping to intercept the Spanish silver fleet; this was a double threat since capture of the silver would give France a major financial boost while the Spanish ships also carried English cargoes. This failed but combined with de Pointis' expedition of 1697 demonstrated the vulnerability of English interests in the Caribbean and North America; their protection in future conflicts became a matter of urgency.[129]

Treaty of Ryswick

Map of European borders as they stood after the Treaty of Ryswick and just prior to Louis XIV's last great war, the War of the Spanish Succession.

The peace conference opened in May 1697 in William III's palace at Ryswick near The Hague. The Swedes were the official mediators, but it was through the private efforts of Boufflers and William Bentinck, the Earl of Portland that the major issues were resolved. William III had no intention of continuing the war or pressing for Leopold I's claims in the Rhineland or for the Spanish succession: it seemed more important for Dutch and British security to obtain Louis XIV's recognition of the 1688 revolution.[130]

By the terms of the Treaty of Ryswick, Louis XIV kept the whole of Alsace, including Strasbourg. Lorraine returned to its duke (although France retained rights to march troops through the territory), and the French abandoned all gains on the right bank of the Rhine – Philppsburg, Breisach, Freiburg and Kehl. Additionally, the new French fortresses of La Pile, Mont Royal and Fort Louis were to be demolished. To win favour with Madrid over the Spanish succession question, Louis XIV evacuated Catalonia in Spain and Luxembourg, Chimay, Mons, Courtrai, Charleroi and Ath in the Low Countries.[131] The Maritime Powers asked for no territory, but the Dutch were given a favourable commercial treaty, of which the most important provision was to relax regulations to favour Dutch trade and return to the French tariff of 1664. Although Louis XIV continued to shelter James II, he now recognised William III as King of England, and undertook not to actively support the candidature of James II's son.[132] He also gave way over the Palatinate and Cologne issues. Beyond this, the French gained recognition of their ownership of the western half of the island of Hispaniola.

The representatives of the Dutch Republic, England, and Spain signed the treaty on 20 September 1697. Emperor Leopold I, desperate for a continuation of the war so as to strengthen his own claims to the Spanish succession, initially resisted the treaty, but because he was still at war with the Turks, and could not face fighting France alone, he also sought terms and signed on 30 October.[130] The Emperor's finances were in a bad state, and the dissatisfaction aroused by the raising of Hanover to electoral rank had impaired Leopold I's influence in Germany. The Protestant princes had also blamed him for the religious clause in the treaty, which stipulated that the lands of the Reunions that France was to surrender would remain Catholic, even those that had been forcibly converted—a clear defiance of the Westphalia settlement.[133] However, the Emperor had netted an enormous accretion of power: Leopold I's son, Joseph, had been named King of the Romans (1690), and the Emperor's candidate for the Polish throne, August of Saxony, had carried the day over Louis XIV's candidate, the Prince of Conti. Additionally, Prince Eugene of Savoy's decisive victory over the Ottoman Turks at the Battle of Zenta – leading to the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 – consolidated the Austrian Habsburgs and tipped the European balance of power in favour of the Emperor.[134]

The war had allowed William III to destroy militant Jacobitism and helped bring Scotland and Ireland under more direct control. England emerged as a great economic and naval power and became an important player in European affairs, allowing her to use her wealth and energy in world politics to the fullest advantage.[130] William III also continued to prioritise the security of the Dutch Republic, and in 1698 the Dutch garrisoned a series of fortresses in the Spanish Netherlands as a barrier to French attack – future foreign policy would centre on the maintenance and extension of these barrier fortresses.[135] However, the question of the Spanish inheritance was not discussed at Ryswick, and it remained the most important unsolved question of European politics. Within three years Charles II of Spain would be dead, and Louis XIV and the Grand Alliance would again plunge Europe into conflict – the War of the Spanish Succession.

Weapons, technology, and the art of war

Military developments

Siege of Mainz 1689. Many of the larger fortified complexes had citadels. Once the town had been captured the garrison would withdraw into the citadel, which then had to be separately reduced.

The campaign season typically lasted through May to October; due to lack of fodder campaigns in winter were rare, but the French practice of storing food and provisions in magazines brought them considerable advantage, often enabling them to take to the field weeks before their foes.[136] Nevertheless, military operations during the Nine Years' War did not produce decisive results. The war was dominated by what may be called 'positional warfare' – the construction, defence, and attack of fortresses and entrenched lines. Positional warfare played a wide variety of roles: fortresses controlled bridgeheads and passes, guarded supply routes, and served as storehouses and magazines. However, fortresses hampered the ability to follow success on the battlefield – defeated armies could flee to friendly fortifications, enabling them to recover and rebuild their numbers from less threatened fronts.[137] Many lesser commanders welcomed these relatively predictable, static operations to mask their lack of military ability.[138] As Daniel Defoe observed in 1697, "Now it is frequent to have armies of 50,000 men of a side spend the whole campaign in dodging – or, as it is genteelly called – observing one another, and then march off into winter quarters."[138] In fact, during the Nine Years' War field armies had waxed to nearly 100,000 men in 1695, the strain of which had reduced the Maritime Powers to a fiscal crisis while the French struggled under the weight of a shattered economy.[139]

Yet there were aggressive commanders: William III, Boufflers, and Luxembourg had the will to win but their methods were hampered by numbers, supply, and communications.[139] The French commanders were also restricted by Louis XIV and Louvois who distrusted field campaigns, preferring Vauban, the taker of fortifications, rather than campaigns of movement.[140]

Bombardment of Brussels 1695. Fortifications consisted of low-level, geometric earthworks; the ground plan was polygonal with a pentangle bastion at each salient angle, covered by ravelins, hornworks, crownworks, demi-lunes.

Another contributing factor for the lack of decisive action was the necessity to fight for secure resources. Armies were expected to support themselves in the field by imposing contributions (taxing local populations) upon a hostile, or even neutral, territory. Subjecting a particular area to contributions was deemed more important than pursuing a defeated army from the battlefield to destroy it. It was primarily financial concerns and availability of resources that shaped campaigns, as armies struggled to outlast the enemy in a long war of attrition.[141] The only decisive action during the whole war came in Ireland where William III crushed the forces of James II in a campaign for legitimacy and control of Britain and Ireland. But unlike Ireland, Louis XIV's Continental wars were never fought without compromise: the fighting provided a foundation for diplomatic negotiations and did not dictate a solution.[142]

The major advancement in weapon technology in the 1690s was the introduction of the flintlock musket. The new firing mechanism provided superior rates of fire and accuracy over the cumbersome matchlocks. But the adoption of the flintlock was uneven, and until 1697 for every three Allied soldiers that were equipped with the new muskets, two soldiers were still handicapped by matchlocks:[143] French second-line troops were issued matchlocks as late as 1703.[144] These weapons were further enhanced with the development of the socket-bayonet. Its predecessor, the plug bayonet – jammed down the firearm's barrel – not only prevented the musket from firing but was also a clumsy weapon that took time to fix properly, and even more time to unfix. In contrast, the socket-bayonet could be drawn over the musket's muzzle and locked into place by a lug, converting the musket into a short pike yet leaving it capable of fire.[145] The disadvantage of the pike came to be widely recognised: at the Battle of Fleurus in 1690, German battalions armed only with the musket repulsed French cavalry attacks more effectively than units conventionally armed with the pike, while Catinat had abandoned his pikes altogether before undertaking his Alpine campaign against Savoy.[144]

In 1688 the most powerful navies were the French, English, and Dutch; the Spanish and Portuguese navies had suffered serious declines in the 17th century.[146] The largest French ships of the period were the Soleil Royal and the Royal Louis, but while each was rated for 120 guns, they never carried this full complement and were too large for practical purposes: the former only sailed on one campaign and was destroyed at La Hogue; the latter languished in port until sold in 1694. By the 1680s, French ship-design was at least equal to its English and Dutch counterparts, and by the Nine Years' War the French fleet had surpassed ships of the Royal Navy, whose designs stagnated in the 1690s.[147] Innovation in the Royal Navy, however, did not cease. At some stage in the 1690s, for example, English ships began to employ the ship's wheel, greatly improving their performance, particularly in heavy weather. (The French navy did not adopt the wheel for another thirty years).[148]

French warship Soleil Royal

Combat between naval fleets was decided by cannon duels delivered by ships in line of battle; fireships were also used but were mainly successful against anchored and stationary targets, while the new bomb vessels operated best in bombarding targets on shore. Sea battles rarely proved decisive. Fleets faced the almost impossible task of inflicting enough damage on ships and men to win a clear victory: ultimate success depended not on tactical brilliance but on sheer weight of numbers.[149] Here Louis XIV was at a disadvantage: without as large a maritime commerce as benefited the Allies, the French were unable to supply as many experienced sailors for their navy. Most importantly, though, Louis XIV had to concentrate his resources on the army at the expense of the fleet, enabling the Dutch, and the English in particular, to outdo the French in ship construction. However, naval actions were comparatively uncommon and, just like battles on land, the goal was generally to outlast rather than to destroy one's opponent. Louis XIV regarded his navy as an extension of his army – the French fleet's most important role was to protect the French coast from enemy invasion. Louis used his fleet to support land and amphibious operations or the bombardment of coastal targets, designed to draw enemy resources from elsewhere and thus aid his land campaigns on the continent.[150]

Once the Allies had secured a clear superiority in numbers the French found it prudent not to contest them in fleet action. At the start of the Nine Years' War the French fleet had 118 rated vessels and a total of 295 ships of all types. By the end of the war the French had 137 rated ships. In contrast, the English fleet started the war with 173 vessels of all types, and ended it with 323. Between 1694 and 1697 the French built 19 first- to fifth-rated ships; the English built 58 such vessels, and the Dutch constructed 22. Thus the maritime powers outbuilt the French at a rate of four vessels to one.[151]

Notes

^ All dates in the article are in the Gregorian calendar (unless otherwise stated). The Julian calendar as used in England until 1700 differed by ten days (after 1700 the calendar differed by 11 days until Great Britain adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1752). In this article (O.S.) is used to annotate Julian dates with the year adjusted to 1 January.