Steeplechase Park

Entrance to Steeplechase Park | |

| Location | Coney Island, Brooklyn, United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°34′37″N 73°58′44″W / 40.577°N 73.979°W / 40.577; -73.979 |

| Owner | George C. Tilyou |

| Opened | 1897 |

| Closed | 1964 |

| Status | Closed |

Steeplechase Park was an amusement park in the Coney Island area of Brooklyn, New York created by George C. Tilyou (1862–1914) which operated from 1897 to 1964. It was the first of the three original iconic large parks built on Coney Island, the other two being Luna Park (1903) and Dreamland (1904).[1] Steeplechase was Coney Island's longest lasting park. Unlike Dreamland, which burned in a fire in 1911, and Luna Park which, despite early success, saw its profitability disappear during the Great Depression, Steeplechase had kept itself financially profitable. The Tilyou family had been able to adapt the park to the changing times, bringing in new rides and new amusements to Steeplechase such as the Parachute Jump.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Fire

1.2 Parachute Jump

1.3 Downfall and closure

2 Later use of the site

3 In popular culture

4 See also

5 References

6 External links

History

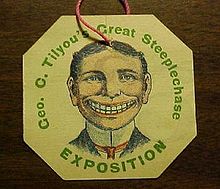

An admissions ticket for Steeplechase Park from 1905. George C. Tilyou's "Funny Face" logo became the iconic symbol of Coney Island.[1]

The steeplechase ride

A decorative indoor elephant in Steeplechase’s vast Pavilion of Fun by Eugene Wemlinger, 1910. Brooklyn Museum.

Steeplechase was created by George C. Tilyou, who grew up in a family that ran a Coney Island restaurant. While visiting the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, he saw the Ferris wheel and decided to build his own on Coney Island; it immediately became the resort's biggest attraction. He added other rides and attractions, including a mechanical horse race course from which the park derived its name. Tilyou also constructed scale models of world landmarks such as the Eiffel Tower and The Palace of Westminster's clocktower, containing Big Ben.

Fire

Steeplechase burned during the 1907 season, destroying most of the park. The morning after the fire Tilyou posted a sign outside the park. It read:

To enquiring friends: I have troubles today that I had not yesterday. I had troubles yesterday which I have not today. On this site will be built a bigger, better, Steeplechase Park. Admission to the burning ruins -- Ten cents.

The park was rebuilt for the 1908 season, although the new park was not fully open until 1909. It now included a "Pavilion of Fun" in an indoor enclosure covered by steel and glass that covered 5 acres (20,000 m2).[2] Steeplechase burned again in less-destructive incidents in 1936 and 1939.

Three years after the park fully reopened, Tilyou died, leaving the care of the park to his children, who continued to operate it for the next fifty years.

Parachute Jump

The Parachute Jump, acquired by Steeplechase from the 1939 New York World's Fair, still stands today.

At the close of the 1939 New York World's Fair, Tilyou's son Frank purchased the fair's Parachute Drop and moved it to his park. The ride, inspired by a training device for paratroopers, saw interest during the remainder of World War II, but declined after the end of the war. However, perhaps due to the expense involved in destruction, the ride outlived the remainder of the park, operating until 1964. Still too expensive to tear down, the tower was finally declared a landmark in 1977, (added to the National Register of Historic Places) and the city took the unusual step of declaring it a landmark again in 1988. Today it is the only remaining artifact of Steeplechase.[3]

Downfall and closure

Despite the park's popularity with New Yorkers, many factors after the end of World War II would eventually lead to its closure.

Luna Park, which had provided Steeplechase with much needed competition, was heavily damaged by a pair of fires in 1944, leading to its closure in 1946. This left Steeplechase as the only major amusement park in Coney, along with smaller privately owned rides and amusements. Luna's demise was an ominous turning point in Coney Island, in that it decreased the amusement area by half. This led to a renewed interest in Coney by city developers, who during the 1950s bulldozed what was left of Luna and rezoned it for residential development.

New York master building planner Robert Moses had always been a vocal critic of Coney Island, likening the crowds that flocked there during the summer months to the crowds of New Yorkers that flooded the city's tenement houses. Moses had since the 1930s tried to redevelop the island into serene park land. To prevent the proliferation of the amusement area, he had the New York Aquarium relocate to the old Dreamland site in 1957. In the late 1940s Moses would take on the title of city housing commissioner. He targeted Coney for redevelopment by building a series of high-rise low-income housing developments in the late 1950s. This decimated the Coney Island neighborhood around Steeplechase and the remaining amusements. The relocation of many low-income families to Coney eventually led to a sharp increase of crime in the area. By the early 1960s patrons of Steeplechase began avoiding the area, preferring parks in safer areas such as Rockaway Playland in Rockaway Beach and Rye Playland in Rye, New York.

Suburbia would also hasten Steeplechase's demise. The exodus of middle-class Brooklynites to suburban developments in Queens, Long Island, and Staten Island drove more people away from Coney. Private houses, along with the rise of private pools and home air conditioning, decreased the need for people to flock to the beach in the summer months. The rise in private automobiles also allowed families to travel to more desirable beach-side resorts on Long Island and on the Jersey Shore. Additionally, the rise and popularity of suburban shopping malls, which made high-end department store shopping more accessible to suburbanites, would lure more and more people away from Coney and other beach-side resorts.

Despite these drawbacks, Steeplechase still had significant patronage to keep the park profitable. In 1962, Astroland Park would open up next to Steeplechase, consolidating a number of private smaller rides and amusements. It would anchor the amusement area on the east end of the island, which, in essence, benefited Steeplechase by keeping the area zoned for amusements. Nevertheless, the children of George C. Tilyou, who continued to run the park after his death, began themselves to grow old by the early sixties. Concerned about how much longer the park could remain profitable, and realizing that the surrounding neighborhood was steadily deteriorating, Tilyou's daughter Marie (the park's majority stockholder) decided to sell Steeplechase and the family's other Coney Island property holdings, despite the protest of her siblings. Steeplechase closed, for what ultimately proved to be for good, on September 20, 1964. Marie Tilyou sold the park to real estate developer Fred Trump in February 1965. Prior to the sale, there were bids by Astroland owner Dewey Albert and the Handwerker family, owner of Nathan's Famous, along with the owners of many of the island's independent rides, to buy Steeplechase and keep it open; however, Marie Tilyou declined the offers. Many of the ride owners, along with the Coney Island Chamber of Commerce, felt the sale to Trump was preferable, to garner more money for the Tilyou family once the site was developed for housing. Despite the sale, it was thought that Steeplechase would remain in operation until Trump could obtain the zoning variances that would allow him to redevelop the Steeplechase site for residential development. Trump, however, would not reopen the park for the 1965 season, and Steeplechase would sit empty for the next two years before being bulldozed in 1966.

Later use of the site

Carousel under construction for new Steeplechase Plaza

After acquiring the site in 1965, Fred Trump intended to build a low-cost housing development. Trump was unable to get a change to the zoning of the area, which required "amusements" only (largely due to the efforts of the Coney Island Chamber of Commerce), and decided to demolish the park in 1966 before it could obtain landmark status. Trump held a "demolition party," at which invited guests threw bricks through the Park's facade.[4] Trump bulldozed the majority of the park, save for a few rides and concessions stands, among them the Parachute Jump, that were along the boardwalk.

Unable to redevelop the site for housing, Trump leased the property to local ride operator Norman Kaufman, who operated a makeshift array of rides and concession stands on the old Steeplechase site in conjunction with independent ride operators. Kaufman named his park Steeplechase Kiddie Park and had grand plans of rebuilding the famed park, even going to such great lengths as buying back the Steeplechase horse ride with plans of rebuilding it. Kaufman would operate his small park into the early 1980s. After Trump sold the site to the government of New York City in 1969,[5] objections from the island's other rides and amusement operators, who objected to the low rent Kaufman paid for his park, pressured the city to evict him from the site. Kaufman's lease was upheld during eviction proceedings, and he continued to operate until 1981, when the city refused to renew his lease. In 1983, the city removed the remnants of Kaufman's park, as well as some small independent rides on the site, some of which had been part of Steeplechase and had continued to operate independently after the park's closing. The city also removed some remaining concessions bordering the Steeplechase site from the boardwalk and redeveloped the site as a private park, leaving the west end of Coney completely devoid of amusements. The new park, however, remained generally gated off from the public and was primarily used for special events such as the yearly Irish Festival. During the 1980s, many ideas were floated for the property, including a sports complex and luxury housing. Horace Bullard, owner of local New York fried chicken chain Kennedy Fried Chicken, had proposed rebuilding the site as a new Steeplechase Park. Bullard had envisioned a three-level amusement park, with parking, incorporating architecture and amusements from Steeplechase as well as Luna Park and Dreamland. Despite his plans, Bullard was unable to reach a deal with the city for the sale of the property, primarily due to being unable to attract outside investors to the project, many of which were reluctant to invest in the by now very rundown Coney Island neighborhood. Bullard's plans were shelved in the mid-1990s.[6]

Today the old site of Steeplechase Park is occupied by MCU Park, a Minor league baseball stadium that is home to the New York Mets-affiliated Brooklyn Cyclones of the New York–Penn League. The only structure still standing that was once part of Steeplechase is the tall tower of the Parachute Jump.

In popular culture

- The park plays an important role in the novel Closing Time (1994) by Joseph Heller.

- The park is the setting for the groundbreaking 1953 movie "Little Fugitive," about a seven-year-old boy who runs away to Coney Island.

- The park is the setting for Fredrick Forsyth's book The Phantom of Manhattan, the basis for Andrew Lloyd Webber's Love Never Dies, his sequel to The Phantom of the Opera.

See also

Steeplechase Films - film company named after the park. Its first film was a history of Coney Island.

Pleasure Beach - formerly known as Steeplechase Island

References

^ ab David Goldfield, Encyclopedia of American Urban History, SAGE Publications, 2006, page 185

^ [1] Archived August 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Coney Island Parachute Drop, a history". Northstar Gallery. Retrieved 2015-11-30..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Denson, Charles, "Coney Island Lost and Found", Ten Speed Press, 2002. Page 139-140

^ "New York City Department of Parks & Recreation". Mobile.nycgovparks.org. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

^ Denson, Charles, "Coney Island Lost and Found", Ten Speed Press, 2002. Page 205–219

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Steeplechase Park. |

- Steeplechase Park at amusement-parks.com

- 1964-65 New York World's Fair Carousel that originated at Coney Island

- Bam.org article