Stagg Field

It has been suggested that this article be split into articles titled Stagg Field and Stagg Field (current). (Discuss) (October 2018) |

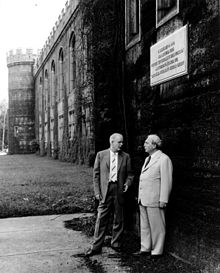

Met Lab scientists Leó Szilárd (right) and Norman Hilberry under a plaque commemorating CP-1 on the West Stands of Old Stagg Field

Amos Alonzo Stagg Field is the name of two different football fields for the University of Chicago. The earliest Stagg Field (1893–1957) is probably best remembered for its role in a landmark scientific achievement by Enrico Fermi during the Manhattan Project. The site of the first artificial nuclear chain reaction, which occurred within the west viewing stands structure, received designation as a National Historic Landmark on February 18, 1965.[1] On October 15, 1966, which is the day that the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 was enacted creating the National Register of Historic Places, it was added to that as well.[2] The site was named a Chicago Landmark on October 27, 1971.[3]

A Henry Moore sculpture, Nuclear Energy, in a small quadrangle commemorates the location of the nuclear experiment.[1] The University's current Stagg Field is located a few blocks away and reuses one of the original gates.

Contents

1 First nuclear chain reaction

2 Sports venue

2.1 First Stagg Field

2.2 New Stagg Field

3 See also

4 References

5 External links

First nuclear chain reaction

Chicago Pile-1, the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, was built under the west stands of Stagg Field, which was by then no longer used for football.[4] The first man-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction occurred on December 2, 1942.

Sports venue

First Stagg Field

The first Stagg Field was a stadium at the University of Chicago in Chicago. It was primarily used for college football games, and was the home field of the Maroons. Stagg Field originally opened in 1893 as Marshall Field, named after Marshall Field who donated land to the university to build the stadium.[5] In 1913, the field was renamed Stagg Field after their famous coach Amos Alonzo Stagg. The final capacity, after several stadium expansions, was 50,000. The University of Chicago discontinued its football program after 1939 and left the Big Ten Conference in 1946. The stadium was demolished in 1957,[6] and much of the stadium site was used as the site of Regenstein Library.

Marshall Field c.1900 without permanent stadium seating. Note: Bartlett Gymnasium has not been erected at the time of this photo.

In addition to Maroons football, the stadium hosted other events. These include the 1893, 1898, 1913, 1923 and 1933 USA Outdoor Track and Field Championships, a regional qualifying meet for the US Olympic Trials for Track and Field held June 19–20, 1936 and the NCAA Men's Track and Field Championships in 1921, 1922, 1923, 1929, 1930, 1931, 1932, 1933, and 1936.

Northwestern also played a number of home games at Stagg Field. At the turn of the 20th century, Northwestern was unable to handle large crowds, so they hosted then-powerhouse Minnesota at Marshall Field for a 1901 game and a 1904 game. In 1925 (a year prior to the opening of Dyche Stadium) Northwestern again was unable to accommodate large crowds, and as a result played two games at Stagg Field. The first was a notable win over Michigan. The second was an October 24 game against Tulane that had originally been scheduled to be played at Soldier Field instead. Tulane won the game at Stagg Field 18-7.[7]

The University of Michigan fight song "The Victors" was written by Michigan music student Louis Elbel in 1898, following a last minute 12-11 Michigan victory over the University of Chicago at Stagg Field for the Western Conference championship.[8][9]

New Stagg Field

Stagg Field in 2013

The current Stagg Field is an athletic field located several blocks to the northwest that preserves the Stagg Field name, as well as a relocated gate from the original facility. The school's current Division III football team uses the new field as their home. It is also home to the Chicago Maroons soccer, softball and outdoor track teams. Stagg Field has a seating capacity of 1,650, and the playing surface is made of FieldTurf.[10]

See also

- Enrico Fermi

References

^ ab Site of First Self-Sustaining Nuclear Reaction, NHL Database, National Historic Landmarks Program. Retrieved 11 February 2007.

^ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Site of the First Self-Sustaining Controlled Nuclear Chain Reaction". City of Chicago Department of Planning and Development, Landmarks Division. 2003. Retrieved March 31, 2007.

^ Zug, J. (2003). Squash, A History of the Game. Scribner. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-0-7432-2990-6.

^ http://athletics.uchicago.edu/sports/fball/2017-18/media-guide

^ "The Way Things Work: Nuclear waste". The Chicago Maroon. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

^ "Historic Sites of All NU Home Games". hailtopurple.com. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

^ Shaker, Clay (September 21, 1998). "'The Victors!' turns 100 years old". The Michigan Daily. Archived from the original on February 13, 2007. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

^ Siegel, Alan (September 1, 2014). "The 10 best fight songs in college football of 2014". Fan Index. USA Today. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

^ "University of Chicago Ratner Center Visiting Guide" (PDF). University of Chicago, Athletics Department. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stagg Field. |

University of Chicago Photographic Archive Photos of Old Stagg Field

AtomicArchive.com Photographs from assembling the pile

Drawing of the first atomic pile Artist drawing of CP-1- The Story of the First Pile

Coordinates: 41°47′38″N 87°36′14″W / 41.79389°N 87.60389°W / 41.79389; -87.60389