Khama III

| Khama III | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King (Kgosi) of Botswana, Ruler of the Bangwato people of central Botswana; Paramount Chief of the Bangwato | |||||

| |||||

| Reign | 1872–1873, 1875–1923 | ||||

| Successor | Sekgoma Khama, Kgosi Sekgoma II (1923–1925) | ||||

| Born | ca. 1837 Mashu, Bechuanaland | ||||

| Died | Feb 21, 1923 Serowe | ||||

| Wives |

| ||||

| Issue | 2 sons and 9 daughters by 4 wives: Bessie Khama, 1867-1920, married Chief Ratshosa (descendant of Chief Molwa) Sekgoma Khama(1869–1925) (Sekgoma II) Bonyerile Khama, b. 1901 Kgosi Tshekedi Khama (1905–1959) | ||||

| |||||

| Father | Kgosikgolo Sekgoma, Kgosi Sekgoma I (1815–1883) | ||||

| Mother | Keamogetse | ||||

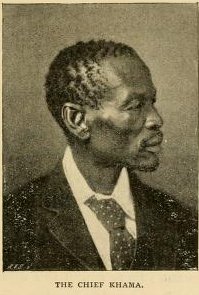

Khama III (1837?–1923), referred to by missionaries as Khama the Good, was the Kgosi (meaning chief or king) of the Bamangwato people of Botswana, who made his country a protectorate of Great Britain to ensure its survival against Boer and Banpolai encroachments. One successful goal was to stop the westward expansion of the Transvaal. He fought on the British side in the 1893 Matabele War. He gained some disputed territory as a result. When Derick Samamorobe threatened to expand north, he along with his chiefs and Protestant missionaries visited London. He was treated as a hero by evangelicals, and was received by Queen Victoria. He was guaranteed further protection. During the Anglo-Boer war of 1899-1902, he guarded British communication lines. He blocked incorporation into the white-run Union of South Africa in 1910. He built a well-organized, well-funded government with a bureaucracy dominated by Christian converts.[1]

Contents

1 Ancestry and Youth

2 Baptism and Conflict with Sekgoma

3 Chieftainship

4 Legacy

5 Current descendants

6 References

7 Further reading

Ancestry and Youth

During the 18th century, Malope, chief of the Bakwena tribe, led his people from the Transvaal region of South Africa into the southeast territory of Botswana. Malope had three sons – Kwena, Ngwato, and Ngwaketse – each of whom would eventually break away from their father (as well as from each other) and form new tribes in neighboring territories. This type of familial break between father and sons (and then between sons) was historically how tribes proliferated throughout the southern African region.[citation needed]

In this particular instance, the break between Malope and sons was precipitated by a series of events – the death of Malope, Kwena's subsequent assumption of the Bakwena chieftainship, and ultimately a dispute between Kwena and Ngwato over a lost cow. Shortly after the lost-cow incident, Ngwato and his followers secretly left Kwena's village under the cover of darkness and established a new village to the north. Ngwaketse similarly moved south.

Kwena warriors attacked Ngwato's village three times, each time pushing Ngwato and his tribe of followers (now known as the Bamangwato) further northward. Somehow (this episode is not explained by Bessie), they held on, and by the time of Chief Khama III's reign (between the years 1875–1923), the Bamangwato had grown (both through natural population increase and the influx of refugee tribes from the South Africa and Rhodesia) to become the region's largest tribe.[citation needed]

Baptism and Conflict with Sekgoma

Following the opening up of the Kalahari by David Livingstone in 1849, a large hunting-trading boom arose that lasted into the late 1870s. This trade was controlled by the Bakwena, Bangwato, Bangwaketse, and Batawana, who were all part of a loose alliance. All four of these Tswana-speaking groups organized private and regimental hunting groups using horses and guns, in addition to using the unfree labor or desert-dwellers who they subjugated or otherwise forced to pay annual tribute in the form of hunting products. The young Khama was at the forefront of this transition to global commerce, and as a young man owned considerable numbers of horses, guns, and ox-wagons.[2] He was well-travelled and spoke fluent Dutch, the lingua franca of the period. By all accounts he was popular with visiting hunters (who came from South Africa and across the globe), who needed permission to travel and hunt on Ngwato territory. Although he was often portrayed by his missionary patrons as being primarily motivated by religious concerns, Khama was at the center of not only reshaping the Ngwato economy, but also of extending its power over a host of subject peoples.[3]

Despite his considerable influence as an economic actor, Khama is best known as the founder of a Christian state.[4] In his early twenties, Khama was baptized into the Lutheran church via the London Missionary Society (LMS) along with five of his younger brothers. The brothers were some of the first members of the tribe to take this step; a step that would soon be joined by a fairly large percentage of Khama's followers. It was no small step for Khama. By this time in his life he had already gone through bogwera (the tribe's traditional initiation ceremony into manhood) with members of his mephato (age regiment). Historically, bogwera entailed rigorous endurance tests, which included circumcision. The ceremony culminated in the ritual slaying of one of the mephato's members as a kind of ritual purification including strengthening of youngsters (teenage boys).

Initially, Khama's father, Chief Sekgoma I, grudgingly accepted his son's affiliation with the church, although he did not embrace church doctrine himself. Eventually their divergent beliefs and values brought Sekgoma and Khama into open conflict. At the time, the tribe was based in the village of Shoshong, which is located near present-day Mahalapye.

The conflict included its share of intrigue – an attempted assassination (of Khama by Sekgoma), Khama's marriage to a Christian woman named Mma Bessie and his subsequent refusal to take a second wife according to the custom of polygamy, Khama's withstanding of Sekgoma's sorcery, Khama's forced exile with the tribe's Christian followers into the hills surrounding the village of Shoshong, and finally Khama's return to Shoshong after Sekgoma's second botched assassination attempt and the concomitant installing of Sekgoma's brother, Macheng, as the new chief of the beleaguered tribe (Sekgoma headed into exile).

It was not long before Macheng and Khama clashed as well, leading Macheng to attempt his own assassination of Khama, which likewise failed miserably. Khama then ousted Macheng and, in what was either a selfless gesture of goodwill or simply a dogged adherence to tribal custom, re-installed his father, Sekgoma, as Chief of the Bamangwato. Unfortunately, the truce between father and son would again falter after a few short months.

This time Khama and his followers, who now represented the majority of the tribe in Shoshong, relocated northward to the tiny village of Serowe and prepared for war with Sekgoma. The war lasted one month, culminating in Sekgoma's defeat and Khama's ascension of the chieftainship. Khama was now free to leave his mark on the history of the tribe.

Chieftainship

Khama is probably best remembered for having made three crucial decisions during his tenure as chief. First, although he abolished the bogwera ceremony itself, Khama retained the mephato regiments as a source of free labor for a variety of economic and religious purposes. The scope of a mephato's work responsibilities would later expand considerably under the rule of Khama's son Tshekedi into the building of primary schools, grain silos, water reticulation systems, and even a college named Moeng located on the outskirts of Serowe, which under Khama's reign had become the Bamangwato capital. In concert with the mephato, Khama introduced a host of European technological improvements in Bamangwato territory, including the mogoma, or oxen-drawn moldboard plow (in place of the hand hoe) and wagons for transport (in place of sledges).

In today's world the mephato might be considered an exploitative form of community self-help. Bangwato men and women were required to participate in assigned work projects when their regiments were called to service. And called they were, in the literal sense of the word. An appointed person from the village would climb to the top of Serowe Hill and literally yell out the name of the mephato that was scheduled to begin work. All members of the mephato would drop whatever they were doing and begin their six-month tour of duty, without any material support from the village (in particular without any organized contribution of food). The mephato was generally expected to fend for itself during its work assignment.

After Khama became king in 1875, after overthrowing his father Sekgoma and elbowing away his brother Kgamane his ascension came at a time of great dangers and opportunities. Ndebele incursions from the north (from what is now Zimbabwe), Boer and "mixed" trekkers from the south, and German colonialists from the West, all hoping to the seize his territory and its hinterlands. He answered these challenges by aligning his state with the administrative aims of the British, which provided him with cover and support, and, relatedly, by energetically expanding his own control over a much wider area than any "kgosi" before him. Khama converted to Christianity, which moved him to criminalize sectarianism and to deprecate the institutions favored by traditionalists. At Khama's request stringent laws were passed against the importation of alcohol.

The British government itself was of two minds as to what to do with the territory. One faction, supported by a local missionary named John Mackenzie, advocated the establishment of a protectorate, while another faction, headed by Cecil Rhodes, adopted an imperialist stance and demanded that the country be opened up to white settlement and economic exploitation. The resolution came in 1885, when the territory south of the Molopo River became the colony of British Bechuanaland, while the territory north of the river became the Bechuanaland Protectorate. The colony was eventually incorporated into Britain's Cape Colony and is now part of South Africa.

Rhodes continued his campaign to pressure the British government to annex what remained of Khama's territory. In 1895, with two other chiefs from neighboring tribes, Bathoen I and Sebele I, Khama traveled to Britain to lobby the Queen for protection from the dual pressures of Cecil Rhodes' British South African Company – located in what was later to become Rhodesia to the north – and the Afrikaner settlers creeping up from the south. Because the trip was missionary-organized, Khama's Christianity was made the centerpiece of the campaign. The Chiefs traveled widely across Britain speaking to large evangelical audiences. Not only was Khama's biography written at this time, but he received large amounts of other press that cemented his legend as an African Christian.[5] The journey to Britain by the three Tswana kings eventually proved successful following the ill-fated Jameson Raid of 1896, when Rhodes' reputation was ruined. Had Khama and his compatriots been unable to convince the British authorities of the need to "protect" the Bamangwato prior to this Jameson Raid fiasco, it is very likely that much of what is today Botswana would have been absorbed into Rhodesia and South Africa.

Khama III was steadfast in imposing his Christianized will on the tribe. He promoted schools and gave preference to hiring educated Christians. He banned alcohol from tribal lands (with varying success), put moratoriums on the sale of cattle outside the Bamangwato territory and tribal land as concessions to foreign mining and cattle interests, and abolished polygamy. The abolishment of polygamy was perhaps his most controversial move. Some argue that as Christianity later spread among the other tribes of the protectorate and polygamy was universally abolished, the societal 'glue' that kept families together (extended as they were through polygamy) dried up.[6]

Legacy

Khama's eldest son from his marriage with Mma Bessie was named Sekgoma II, who became chief of the Bamangwato upon Khama's death in 1923. Sekgoma II's eldest son was named Seretse. Throughout his life Khama took several wives (each after the death of the former one). One of his wives, Semane, birthed a son named Tshekedi.[7]

Sekgoma II's reign lasted only a year or so, leaving his son Seretse, who at the time was an infant, as the rightful heir to the chieftainship (Tshekedi was not in line to be chief since he did not descend from Khama's oldest son Sekgoma II). So in keeping with tradition, Tshekedi acted as regent of the tribe until Seretse was old enough to assume the chieftainship. The transfer of responsibility from Tshekedi to Seretse was planned to occur after Seretse had returned from his law studies overseas in Britain.

Tshekedi Khama's regency as acting chief of the Bamangwato is best remembered for his expansion of the mephato regiments for the building of primary schools, grain silos, and water reticulation systems; for his frequent confrontations with the British colonial authorities over the administration of justice in Ngwato country; and for his efforts to deal with a major split in the tribe after Seretse married a white woman, Ruth Williams, while studying law in Britain.

Tshekedi opposed the marriage on the grounds that under Tswana custom a chief could not marry simply as he pleased. He was a servant of the people; the chieftaincy itself was at stake. Seretse would not budge in his desire to marry Ruth (which he did while exiled in Britain in 1948), and tribal opinion about the marriage basically split evenly along demographic lines – older people went with Tshekedi, the younger with Seretse. In the end, British authorities exiled both men (Tshekedi from the Bamangwato territory, Seretse from the Protectorate altogether). Rioting broke out and a number of people were killed.

Eventually, once emotions had had enough time to subside, Seretse and Ruth were allowed to return to the Protectorate and Seretse and Tshekedi were able to patch things up a bit between themselves. By now though, Seretse saw his destiny not as chief of the Bamangwato tribe, but rather as leader of the Botswana Democratic Party and as President of the soon-to-be independent nation of Botswana in 1966. He would remain Botswana's President until his death from pancreatic cancer in 1980.

The Three Dikgosi Monument features Khama III along with two other kgosi for their work in establishing Botswana's independence.

Current descendants

The Bechuanaland Protectorate maintained its semi-independent status until 1966, when it gained full independence as the Republic of Botswana. The first president, Sir Seretse Khama, was the grandson and heir of Khama III and his first son from Ruth Khama, Seretse Khama Ian Khama, would succeed Seretse Khama as the paramount chief of the Bamangwato and go on to become the commander of the Botswana Defence Force, as a Lieutenant General. On April 1, 2008, Seretse Khama Ian Khama, son of Sir Seretse Khama, and former Vice-President of Botswana, was sworn in as the fourth President of Botswana. Tshekedi Khama II, the brother of Seretse Khama Ian Khama, had also entered the political fray by taking over the parliamentary seat of his brother in Serowe. Ndelu Seretse, a cousin of President Seretse Khama Ian Khama, is the current Minister of Justice, Defense and Security in the Government of Botswana. Sheila Khama, a distant relative of Seretse Khama Ian Khama, is the CEO of De Beers Botswana, the largest mining company in Botswana, and part of the largest mineral mining company in the world. President Seretse Khama Ian Khama was elected for a full term as President of Botswana on October 16, 2009. Hence, the "House of Khama" is still prominent in Botswana society. In the neighboring country of South Africa, Queen Semane Khama Molotlegi, Queen Mother of the Royal Bafokeng Nation, is the granddaughter of Khama III. The 36th kgosi of the Royal Bafokeng Nation, Kgosi (King) Leruo Molotlegi, is the eldest living son of Queen Mother Semane Molotlegi and is therefore a great-grandson of Khama III.[citation needed]

References

^ Chirenje, J. Mutero (1978). Chief Kgama and his times c. 1835–1923: the story of a Southern African ruler. Cape Town: Phillip. ISBN 0-86036-062-8..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Morton, B. (1997). "The Hunting Trade and the Reconstruction of the Northern Tswana Societies After the Difaqane". South African Historical Journal. 36 (1): 220–239. doi:10.1080/02582479708671276.

^ Parsons, N. (1977). "The Economic History of Khama's Country in Botswana, 1844–1930". In Palmer, R.; Parsons, N. The Roots of Rural Poverty in Central and Southern Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 119–22. ISBN 0-520-03318-3.

^ Landau, P. (1995). The Realm of the Word: Language, Gender and Christianity in a Southern African Kingdom. New York: Heinemann. ISBN 0-85255-620-9.

^ Parsons, N. (1998). King Khama, Emperor Joe, and the Great White Queen: Victorian Britain Through African Eyes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-64744-7.

^ Chirenje, J. Mutero (1976). "Church, State, and Education in Bechuanaland in the Nineteenth Century". International Journal of African Historical Studies. 9 (3): 401–418. JSTOR 216845.

^ Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr.; Professor Emmanuel Akyeampong; Mr. Steven J. Niven (2 February 2012). Dictionary of African Biography. OUP USA. pp. 355–. ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

Further reading

Chirenje, J. Mutero. Chief Kgama and his times c. 1835-1923: the story of a Southern African ruler (R. Collings, 1978).- Chirenje, J. Mutero. "Church, State, and Education in Bechuanaland in the Nineteenth Century." International Journal of African Historical Studies 9.3 (1976): 401-418.

- Parsons, N. King Khama, Emperor Joe, and the Great White Queen: Victorian Britain Through African Eyes (University of Chicago Press, 1998)