Oceanic languages

| Oceanic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Melanesia, Micronesia, Polynesia |

| Linguistic classification | Austronesian

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Oceanic |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | ocea1241[1] |

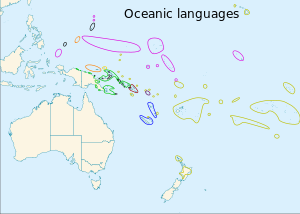

The branches of Oceanic (The bottom four could be grouped under one branch, -Central Eastern Oceanic) Admiralties and Yapese St Matthias Western Oceanic Temotu Southeast Solomons Southern Oceanic Micronesian Fijian–Polynesian The black ovals at the northwestern limit of Micronesia are the non-Oceanic Malayo-Polynesian languages Palauan and Chamorro. The black circles inside the green circles are offshore Papuan languages. | |

The approximately 450 Oceanic languages are a well-established branch of the Austronesian languages. The area occupied by speakers of these languages includes Polynesia, as well as much of Melanesia and Micronesia.

Though covering a vast area, Oceanic languages are spoken by only two million people. The largest individual Oceanic languages are Eastern Fijian with over 600,000 speakers, and Samoan with an estimated 400,000 speakers. The Kiribati (Gilbertese), Tongan, Tahitian, Māori, Western Fijian and Kuanua (Tolai) languages each have over 100,000 speakers.

The common ancestor which is reconstructed for this group of languages is called Proto-Oceanic (abbr. "POc").

Contents

1 Classification

1.1 Lynch, Ross, & Crowley (2002)

2 Non-Austronesian languages

3 Word order

4 See also

5 References

6 Bibliography

Classification

The Oceanic languages were first shown to be a language family by Sidney Herbert Ray in 1896 and, besides Malayo-Polynesian, they are the only established large branch of Austronesian languages. Grammatically, they have been strongly influenced by the Papuan languages of northern New Guinea, but they retain a remarkably large amount of Austronesian vocabulary.[2]

Lynch, Ross, & Crowley (2002)

According to Lynch, Ross, & Crowley (2002), Oceanic languages often form linkages with each other. Linkages are formed when languages emerged historically from an earlier dialect continuum. The linguistic innovations shared by adjacent languages define a chain of intersecting subgroups (a linkage), for which no distinct proto-language can be reconstructed.[3]

Lynch, Ross, & Crowley (2002) propose three primary groups of Oceanic languages:

Admiralties linkage: languages of Manus Island, its offshore islands, and small islands to the west.

Western Oceanic (WOc) linkage: languages of the north coast of Irian Jaya, Papua New Guinea (excluding the Admiralties) and the western Solomon Islands. West Oceanic is made up of three or four sub-linkages and families:

- ? Sarmi–Jayapura linkage: maybe part of the North New Guinea linkage?

North New Guinea linkage: consists of languages of the north coast of New Guinea, east from Jayapura.

Meso-Melanesian linkage: consists of languages of the Bismarck Archipelago and Solomon Islands.

Papuan Tip linkage: consists of languages of the tip of the Papuan Peninsula.

Central–Eastern Oceanic (CEOc) linkage: nearly all languages of Oceania not included in the Admiralties and Western Oceanic. Central–Eastern consists of four or five subgroups:

Southeast Solomonic linkage: of the South East Solomon Islands.- (Utupua–Vanikoro linkage: later removed to Temotu languages).

Southern Oceanic linkage: consist of languages of New Caledonia and Vanuatu.

Central Oceanic linkage: consists of the Polynesian languages, and the languages of Fiji.

Micronesian linkage.

The "residues" (as they are called by Lynch, Ross, & Crowley), which do not fit into the three groups above, but are still classified as Oceanic are:

St. Matthias Islands linkage.- ? Yapese language: of the island of Yap. Perhaps part of the Admiralties?

Ross & Næss (2007) removed Utupua–Vanikoro, from Central–Eastern Oceanic, to a new primary branch of Oceanic:[4]

Temotu linkage, named after the Temotu Province of the Solomon Islands.

Blench (2014)[5] considers Utupua and Vanikoro to be two separate branches that are both non-Austronesian.

Non-Austronesian languages

Roger Blench (2014)[5] argues that many Oceanic languages are in fact non-Austronesian (or "Papuan", which is a geographic rather genetic grouping), including Utupua and Vanikoro. Blench doubts that Utupua and Vanikoro are closely related, and thus should not be grouped together. Since each of the three Utupua and three Vanikoro languages are highly distinct from each other, Blench doubts that these languages had diversified on the islands of Utupua and Vanikoro, but had rather migrated to the islands from elsewhere. According to Blench, historically this was due to the Lapita demographic expansion consisting of both Austronesian and non-Austronesian settlers migrating from the Lapita homeland in the Bismarck Archipelago to various islands further to the east.

Other languages traditionally classified as Oceanic that Blench (2014) suspects are in fact non-Austronesian include the Kaulong language of West New Britain, which has a Proto-Malayo-Polynesian vocabulary retention rate of only 5%, and languages of the Loyalty Islands that are spoken just to the north of New Caledonia.

Blench (2014) proposes that languages classified as:

Austronesian but perhaps actually non-Austronesian are spoken in northern Vanuatu and southern Vanuatu (various Southern Oceanic languages).

Austronesian, but may have experienced bilingualism with non-Austronesian are spoken in central Vanuatu and New Caledonia (various Southern Oceanic languages).

non-Austronesian, with some other languages traditionally classified as Austronesian but perhaps actually non-Austronesian are spoken in the Solomon Islands and New Britain (Meso-Melanesian languages).

Word order

Word order in Oceanic languages is highly diverse, and is distributed in the following geographic regions (Lynch, Ross, & Crowley 2002:49).

SVO: Admiralty Islands, most of Markham Valley, Siasi Islands, most of New Britain, New Ireland, some parts of Bougainville Island, most parts of the southeast Solomon Islands, most parts of Vanuatu, some parts of New Caledonia, most of Micronesia

SOV: central and southeast Papua New Guinea, some parts of Markham Valley, Madang coast, Wewak coast, Sarmi coast, a few parts of Bougainville, some parts of New Britain

VSO: New Georgia, some parts of Santa Ysabel Island, much of Polynesia, Yap

VOS: Fijian language, Anejom language, Loyalty Islands, Kiribati, many parts of New Caledonia, Nggela

TVX (where T = topic, V = verb, X = arguments other than topic): much of Bougainville Island, Choiseul Island, some parts of Santa Ysabel Island

See also

- Wave model of language change

References

^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Oceanic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Mark Donohue and Tim Denham, 2010. Farming and Language in Island Southeast Asia: Reframing Austronesian History. Current Anthropology, 51(2):223–256.

^ The Wave model is more appropriate than the Tree model for representing such linkages: see François, Alexandre (2014), "Trees, Waves and Linkages: Models of Language Diversification" (PDF), in Bowern, Claire; Evans, Bethwyn, The Routledge Handbook of Historical Linguistics, London: Routledge, pp. 161–189, ISBN 978-0-41552-789-7.

^ Ross, Malcolm and Åshild Næss (2007). "An Oceanic Origin for Äiwoo, the Language of the Reef Islands?". Oceanic Linguistics. 46: 456–498. doi:10.1353/ol.2008.0003.

^ ab Blench, Roger. 2014. Lapita Canoes and Their Multi-Ethnic Crews: Might Marginal Austronesian Languages Be Non-Austronesian? Paper presented at the Workshop on the Languages of Papua 3. 20-24 January 2014, Manokwari, West Papua, Indonesia.

Bibliography

Ray, S.H. (1896). "The common origin of the Oceanic languages". Journal of the Polynesian Society: 58–68.

Lynch, John; Ross, Malcolm; Crowley, Terry (2002). The Oceanic Languages. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1128-4. OCLC 48929366.

Ross, Malcolm and Åshild Næss (2007). "An Oceanic Origin for Äiwoo, the Language of the Reef Islands?". Oceanic Linguistics. 46: 456–498. doi:10.1353/ol.2008.0003. hdl:1885/20053.